Dette ph

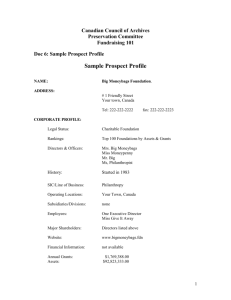

advertisement