Exploring the Drivers of Environmental Behaviour in the World of Wine

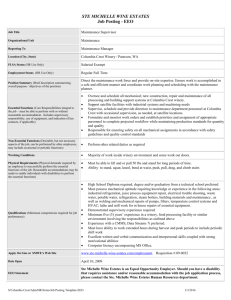

advertisement

Exploring the Drivers of Environmental Behaviour in the World of Wine: A Policy Oriented Review Barry Wright * (Corresponding Author) Associate Dean, Faculty of Business Brock University bwright@brocku.ca Carman Cullen Associate Professor, Marketing Brock University ccullen@brocku.ca Linda Bramble Writer/wine educator lbramble@cogeco.ca Edward Madronich Owner Flat Rock Cellars Winery edward@flatrockcellars.com ABSTRACT We offer that environmental practices are driven by three important considerations, ‘business performance’, ‘regulation’, and ‘personal perspectives’ and moderated by two others – ‘organizational slack’ and ‘age’. It has been said that a person has two reasons for doing something – a good reason and a real one. In response to our question as to what motivates organizations or individuals to adopt environmental practices, it would appear there are three good reasons for going green, a business one, a forced or adopted one (regulation) and a personal one. Which one is an individual’s real reason is, for the moment, still open for discussion. Key Words: sustainability, green, biodynamics, business, wine Language of the full paper: English Exploring the Drivers of Environmental Behaviour in the World of Wine: A Policy Oriented Review Abstract We offer that environmental practices are driven by three important considerations, ‘business performance’, ‘regulation’, and ‘personal perspectives’ and moderated by two others – ‘organizational slack’ and ‘age’. It has been said that a person has two reasons for doing something – a good reason and a real one. In response to our question as to what motivates organizations or individuals to adopt environmental practices, it would appear there are three good reasons for going green, a business one, a forced or adopted one (regulation) and a personal one. Which one is an individual’s real reason is, for the moment, still open for discussion. Our method in this paper is simple. We have conducted a review of the relevant literature, and then used this review as the basis for interviews with a few central players in the Niagara, Canada wine industry. Our goal was to identify, categorize and analyze the various drivers of environmentally sound behaviour in vineyards and wineries. We attempt to illustrate the more important issues with examples provided by the interviewees, and then examine the policy implications of our findings. Introduction The idea of sustainable winemaking – an approach that limits the negative impact of winemaking on the environment while enhancing the economic returns to the winery – has grown enormously in popularity in recent years. Individually, small and large wineries are seeking to develop practices and policies that promote a more ecological, sustainable and, in turn, socially responsible organization. Collectively, wineries are starting to work in a cooperative way to develop sustainable regional and national programs. These include organizations such as Agriculture Raisonée in France, Sustainable Winegrowing in New Zealand, Integrated Production of Wine in South Africa, the California Integrated Winemaking Alliance and the Sustainable Winemaking Ontario in Canada. Each of these “green” organizations has attracted increasing numbers of members and is gaining more influence in the world-wide wine industry. While it is clear that there is a growing concern for sustainability in the industry it is unclear as to what the key drivers are that entice wine makers into sustainable environmental behaviour. At present, there is a dearth of work on the causal drivers of small to medium enterprise (SME) environmental behaviour and there is a growing recognition that we need to advance our understanding of why firms behave environmentally (Bansal and Roth, 2000; Geiser and Crul, 1996; Gladwin, 1993; Marshall, Cordano, & Silverman, 2005). Bansal and Roth (2000) argue that an explanation of business responsiveness is needed for two reasons. First, it would help organizational theorists understand the factors that bring on environmental behaviour and, second, it would serve to explain what mechanisms stimulate environmentally sustainable organizations (Williamson, LynchWood & Ramsayat, 2006). Accordingly, a research opportunity exists to develop a “motivational” model that identifies distinct conceptual categories of ecological stimuli (Bansal & Roth, 2000). The aim of our paper is first to provide a thorough review of recent literature on sustainable environmental practices in the wine industry to propose a theoretical model as to the drivers of wine environmentalism. While there maybe many uses for this model, our second purpose is to look at ways that this model might inform policy makers of strategies to induce environmental practices. One might wonder why the focus on wine? We have two reasons; the industry has significant economic and environmental impacts and, it is important to our geographical area. Thus, we too have one good reason to study this phenomenon, and one real one. Please see Appendix 1 for a brief overview of the importance of the industry in Ontario, Canada. From an environmental performance perspective, the wine industry does not garner as much attention as does either manufacturing or energy production. However, because the industry does have an environmental imprint due to its use of herbicides; toxic pesticides; fertilizers; water for growing with the possibility for contaminated runoff; energy use to cultivate, sustain, produce and then transform grapes into wine; and the transformation of land from habitat to vineyard, it is obviously a “player” in the environmental movement. Studies have identified several motives for corporate "greening," including: regulatory compliance, competitive advantage, mimetic behaviour, network membership, stakeholder pressures, ethical concerns, critical events, individual values, strategic opportunity, ecological responsibility, business performance, managerial attitudes, subjective norms, voluntary actions, and top management initiatives (Bansal & Roth, 2000; Dillon & Fischer, 1992; Lawrence & Morell, 1995; Marshall, Cordano, & Silverman, 2007). Although these studies illustrate widespread interest in understanding corporate greening, it is still difficult to predict ecological responsiveness (Bansal & Roth, 2000). We propose a more parsimonious approach. We believe these identified motives can be grouped into three broad categories – the Business Case, the Regulatory Case, and the Individual Case. Each of these categories will be discussed as we identify a model that explains organizational ecological responsiveness by identifying motivations for adopting ecological initiatives. We also propose two moderator variables – organizational slack and age that, we believe will significantly impact the efficacy of our proposed three primary drivers of environmental behaviour (see Diagram 1). Diagram 1: Drivers of Organizational Responsiveness with Moderators Organizational Slack Age Business Case Regulatory Case Individual Case Adoption of Best Practices Business Case Seldom is the business case listed as the primary motive for “going green” by winery owners and managers. Yet, our interviews to date suggest that the business case is never too far below the surface. It would be uncharitable, and hopelessly cynical, for us to suggest that the “real” reason for being environmentally concerned is sales or profit; but it would be hopelessly naïve to suggest that the business case is irrelevant in the adoption of green practices. Policy makers interested in promoting environmentally sound practices in the wine industry need to understand, and use, each of the drivers of this behaviour. The traditional Marketing Mix framework known as the four Ps provides a reasonable, general structure for examining the business case for an environmentally sensitive approach to winemaking. A consistent component of the business case made by winery owners and managers is that environmental balance and sustainability make for a better product; the first of the four Ps. Jens Gemmrich, owner of Niagara, Canada’s Frogpond Farms1 – a fully organic winery as certified by OCPP/Pro-Cert – claims that a healthy, balanced grape does not require intervention to produce wonderful wines; whether the intervention is in the vineyard or the winery. Frogpond does not use insecticides, herbicides, synthetic fungicides, chemical fertilizers; they do have a buffer zone separating their vineyards from other farms, they use solar water heaters, and they purchase their power from a local 1 Much of the portion of the paper specific to Frogpond Farms is the product of interviews conducted by Alison Moyes in 2008. provider that uses wind energy. Frogpond does not use fining agents to clarify the juice prior to fermentation. This focus on the quality of the product, however, should not be construed as the sole reason for the green philosophy of Frogpond. Jens, for example, refuses to sell his icewine to the Orient because of the “carbon cost” that this would entail in shipping the product half-way around the world. Southbrook Vineyards in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Canada’s first winery to achieve biodynamic certification from Demeter has found that consumers in their tasting room (the second P - Place) are fascinated by the specifics of biodynamic practices, and consumers are eager to learn more about the certification and everything it entails. Elena Gayley-Pride, Director of Customer Experience for Southbrook, asserts that consumer fascination with biodynamics is understandable, but the reason for being biodynamic is the deep-rooted philosophy of the owners, Bill and Marilyn Redelmeier and the Director of Winemaking and Viticulture, Ann Sperling. The fact that it also makes a good marketing story is not lost on Gayley-Pride, but she points out that consumers can detect phonies, and they appreciate the consistent message about sustainability that is communicated by Southbrook. The winemaker, Sperling, notes that “Amazing, vibrant wines come from grapes that are raised biodynamically. And the drive behind all of our efforts at Southbrook is to make amazing wine.” Bill Redelmeier added, “Our team at Southbrook was drawn to biodynamics as a way to more fully express the vineyard’s character in our wines.” The third P of the marketing mix, Promotion, is an obvious and significant part of the business case for environmentally sound practices in the wine industry. Southbrook takes advantage of their efforts to “tread lightly on the land” to promote their winery. Other Niagara wineries also utilize their organic philosophies to attract consumers. Featherstone Winery, for example, uses sheep for leaf-pulling and vegetation control. Instead of using “bangers” to deter birds from eating the grapes the owners of Featherstone use a falcon. Both of these practices provide significant public relations benefits for the winery. Finally, the fourth P, Price, is a critical part of the business case for environmentally responsible practices in the wine industry. Increased demand for “green” products suggests that consumers will pay a premium for wines that have been produced with the environment in mind. A second general approach to understanding the business case for environmentally sensitive vineyard and winery practices is based on the writings of Kenichi Ohmae, retired CEO of McKinsey Japan. Ohmae claimed that business strategy could be summed up in “3 Cs”: Focusing on the Consumer, the Competition, and your own Company. Consumer demand is a central issue in the business case for environmental responsibility, with many wineries attempting to be ahead of the curve, proactively providing environmentally responsible wine. The business case for green wineries may also be based on responses to competitors’ successes in adopting ecologically friendly practices. The third C, the “company” variable of Ohmae’s model, will be discussed in a subsequent discussion of the moderators of green winery activities. The wine consumer has been found to be significantly more “green minded” than the average consumer (Beverage World, 2007). In fact, those who consume brut extra dry were found to be four times more likely to seek out and purchase organic produce; many other varietal drinkers were between two and three times as “green” as the non wine drinking consumer. There appears to be a solid business case for a “green” position based on the Beverage World study alone. Consumers find environmental issues relevant. There is, however, significant confusion in the minds of consumers with respect to differentiating among sustainable practices, organic, “green,” environmentally conscious, “low carbon footprint,” ecologically conscious, etc. (Western Farm Press, 2008). The business case for “green” winery practices requires significant consumer education. Anecdotal cellar door evidence in Niagara suggests that consumers are interested; now the industry must help them understand. Frantz (2008) notes that some restaurants have begun using explanations and definitions of terms such as organic, biodynamic and sustainable at the top of the wine list. Cellar doors would seem to be a logical location for a similar approach in Niagara. The competitive environment will encourage more participation in environmentally friendly winemaking practices. A recent study (Western Farm Press, 2008) found that eighty percent of vineyard representatives in California reported using sustainable farming practices on at least part of their acreage in 2008, and that forty-six percent have been, or plan to be, marketing their grapes as “sustainable” or “organic” during the current or upcoming year. It has become increasingly apparent that there is a solid business case for environmentally responsible behaviour in the wine industry. These practices can result in great product that consumers may be willing to pay a premium to enjoy. The entire process lends itself to intriguing stories that can be used for promotion in general, and specifically for selling at the cellar door. Consumer demand appears to be increasing, and the competitive environment suggests that wineries ignore “green” at their own risk. Regulatory Case A variety of regulatory reasons “encourage” organizations to adopt green practices including environmental performance standards, codes of conduct, best practices, certification standards and governmental reporting and monitoring. These “selfregulatory” and / or “governmental regulations” aim to either promote or force the private sector to manage their operations in environmentally friendly ways. Speaking first of governmental controls, it is a widely held view that government regulation has a negative impact on business competitiveness as it fosters an overly burdensome regulatory environment on smaller firms (Fletcher, 2001; Williamson, Lynch-Wood and Ramsayat, 2006). The point being that SMEs have fewer resources to commit and those regulations are often designed to control the behaviour of large organizations thereby creating excessive hardship for smaller organizations. To escape governmental regulation, many private companies have found that adopting inter-firm cooperative instruments, fundamentally through the creation of business associations, is a fruitful approach. Zadex (2006) examined the wisdom of this collaborative governance and found that it provides an opportunity to deliver green goods through collaboration as opposed to government control. In this case, corporate responsibility is transform into corporate accountability (Young & Utting, 2005), changing the business agenda from a response to controls to a voluntary, accountable one. However, rather than cooperatively adopting strategies, firms may be compelled to react to the strategies of their competitors where failing to do so might disadvantage them (e.g., market positioning). These “isomorphic” effects have been found across different industries and strategic groups (Bansal and Roth, 2000). Interestingly, in the Niagara region of Ontario, Canada the wine industry has taken the lead in developing a self-regulatory charter to advance the environmental sustainability of winemaking in Ontario. Beginning in 2006 the industry realized the importance of being “ahead of the curve” when it came to environmental issues. As a result, the industry came together to develop Sustainable Winemaking Ontario: An Environmental Charter for the Wine Industry. The goals were to: improve the environmental performance of the wine industry in Ontario, continually improve the quality of wine growing and winemaking in an environmentally responsive manner, provide a way to address consumer and resident questions in relation to the environment and the wine industry, add value to the wine industry in Ontario. Two key documents were developed for these efforts. The first was Developing Energy Benchmarks for the Ontario Wine Industry. One cannot move forward without knowing where you are. This document outlined the baseline for the Ontario wine industry. It established benchmarks clearly defining the performance of wineries. The second document, Energy Best Practices for Wineries, created the road map for the industry to follow. Key to this document is an interactive spreadsheet that allows wineries to measure themselves against hundreds of criteria and ultimately develop a score from which to measure their progress. Not only did the industry identify what it means to be environmentally responsible it identified clearly how it is to be measured and how one can improve moving forward. The program was first initiated in 2007 with 17 wineries participating, growing to over 40 in 2008. Currently, the program is voluntary and self regulating. However, in the coming years a certification program is being developed with audit and compliance measures adopted. Ultimately, self regulation will ensure we continue to improve environmental performance. Case for Individual Concern The discussion regarding corporate social responsibility and being environmentally responsible has primarily addressed organizational rationale and activities with little being said about the individual characteristics and behaviors that promote this development. While there is a dearth of research to specifically draw upon, there are a few papers to point us in useful directions. In particular, one study of 643 middle managers in five multinational corporations supports our contention that individual values, affect and reasoning matter for stimulating environmental actions in organizations (Crilly, Schneider & Zollo, 2008). To expand, the authors found that self-transcendence values (universalism and benevolence), positive affect, moral and reputational-based reasoning styles increase the inclination for individuals to engage in socially responsible behaviour such as going green (Crilly, Schneider, & Zollo, 2008). The study highlights the importance of the human dimension in creative problem solving and innovation necessary for undertaking voluntary environmental strategies. Sharma (2000) found that the greater the extent to which managers perceive environmental concern as central to their company's identity, the greater the likelihood that they will interpret environmental issues as opportunities rather than as threats. Sharma’s study highlights the importance of the threat and opportunity considerations in the way managers interpret issues. In view of that, it is possible to see that it can be individual awareness and then concern that drives environmental action. We also offer that individual ecological responsibility is a motivation that stems from the concern that an individual has for his or her social obligations. A salient feature of this motivation is a concern for the social good. We propose that individuals might be motivated by a sense of obligation or responsibility rather than out of self interest and this result in them championing ecological responses (Bucholz, 1991; L'Etang, 1995). Our stories from the field on individual motivation include David Feldberg, office furniture design and manufacturing magnate, who turned his international company, Teknion, into a $500 million powerhouse, by incorporating serious sustainable practices, into all their operating practices designed to reduce their environmental impact. When, in the early 2000s he decided to turn his passion for wine into a winery in Niagara (Stratus Wines) it went without saying that the winery would also be built with sustainability in mind. Even though the design added roughly fifteen per cent to the total cost, by this time Feldberg had evidence that not only was environmental stewardship the right thing to do, there was an economic pay back between three to eight years. With its gravity-fed flows and geothermal wells it was a buzz in the wine community, and shortly after opening it became a model for winery design. It was the first winery in the world to be certified under the Leadership Energy Environmental Design (LEED) program by meeting criteria in five main categories: sustainable site, water efficiency, energy efficiency, green materials and indoor environment quality. Financier Moray Tawse was also motivated to go green when he built his winery (Tawse Winery) in 2005 just a few kilometers away from Stratus. His extensive travelling throughout Burgundy and his conversations with vignerons of the wines he liked best triggered his enthusiasm for sustainable practices. As a connoisseur of fine wine, Tawse saw first hand how vineyards that used green practices such as organic and biodynamic principles simply had healthier fruit. What prevented so many others from going into the wine business to implement similar principles was money, time and energy, all of which Tawse had sufficient amounts. Although the winery design is environmentally friendly, his focus has been on the vines where he practices biodynamic farming. The vintage of 2008 was the proof for him that he had made the right decision. His Pinot Noir not only made it through a tough vintage, his fruit was more balanced, ripened earlier, fermented sooner and faster than other fruit he had purchased from other growers. Next year he plans on using a horse and plow to avoid compacting the soil. The critical incident that gave Ed Madronich, President of Flat Rock Cellars, incentive to install a geothermal heating and cooling system, the first one installed in Ontario at the time (in 1999) was, in part, simply good business. He wanted to preserve the winery’s soil and environment while producing great wine. The other reason, the real one, was his four-year old daughter. He didn’t want her inheriting a poisoned piece of land that didn’t grow very good grapes. Moderators We propose that there are two moderator variables that will affect the adoption of environmental practices in grape growers or wine makers – organizational slack and age. Organizational slack is an indicator of the amount of flexibility an organization has to focus on new initiatives. We propose that without fiscal flexibility environmental practices might be perceived as too costly, difficult, time-consuming, or not part of the core business goals to be worthwhile. The greater the degree of discretionary slack provided to managers in managing the business/natural environment interface, the greater the likelihood of their interpreting environmental issues as opportunities rather than as threats and, be motivated to adopt best practices (Sharma, 2000). It is often said that even a good idea takes a generation to achieve the change. For our discussion, this is a central point. The importance of green practices has been spread many different ways; in our community, for example, one key way is through the public school system. For twenty years or more, educators have highlighted the need for and have implemented green practices around recycling and waste reduction. These “seeds” of awareness have now sprouted with a new generation of wine makers already in tune with the environmental message. We propose that the age of the leader or leadership team will significantly effect the adoption of environmental practices with younger leaders being more proactive. We are, however, somewhat troubled by a recent major research study of 6,036 Canadians (Marketing News, 2008) that suggested that the least likely group to purchase environmentally responsible goods are men and women between the ages of 25 and 34, with the most likely group being women between the ages of 55 and 59. There are numerous plausible hypotheses to explain these variations, but one explanation is as likely as the other until specific, targeted scientific research is conducted. Challenges of implementing ecological sustainability and the Policy Alternatives Our review has highlighted that there appears to be three main problems with implementing environmentally friendly practices in organizations. First, practices might be perceived as too costly, difficult, time-consuming, or not part of the core business goals to be worthwhile. Shareholders might have little willingness to initiate needed change. Second, there might be a lack of concrete government regulatory support for supporting a sustainability plan; or, a lack of cooperative accountability measures enacted to stimulate sustainability. Third, there might be a lack of genuine support from organizational leaders. A champion is needed at the top in any change program for without a responsible individual little will be done. Even if senior management is on board, errors in communication might result in poor understanding by rank and file organizational members on the sustainability principles and the rationale for them; individual ideals might not be translated into everyday practices (Willard, 2005). Policy makers should draw from this review to enact courses of action that foster a decision environment that will make it “easy” for wine leaders to adopt environmental practices. First, policy makers must understand how to ensure that the ‘business case’ is a powerful one. Examples might include: tax incentives provided for the purchase of new ‘green’ equipment; in Ontario where the government controls the distribution channel, important shelf-space might be held in contingence for environmentally friendly producers. While unpopular with producers, it has been argued that regulatory structures which outline minimum standards are likely the main driver of environmental actions in SMEs (Williamson, Lynch-Wood and Ramsayat, 2006). In their study Williamson et al., (2006) suggested that environmental practices are driven by two important considerations, ‘business performance’ and ‘regulation’, and found that regulation produced higher levels of environmental activity (Williamson, Lynch-Wood & Ramsay, 2006). Bianchi and Noci (1998) also support this hypothesis as they found that large corporations are the primary adopters of pro-active environmental strategy, whereas SMEs tend to comply with external pressures, thus adopting a re-active strategy. This being the case, it will be important that regulatory, either self or governmental, strategies are developed to motivate growers and wine makers to adopt environmentally friendly policies. Lastly, policy makers also need to create motivational strategies that ‘sell’ individuals on the benefits of a greener world through a variety of public awareness campaigns. This has been successful in the smoking cessation program although it has taken a long time and only worked when used in conjunction with a regulatory campaign. One other important challenge that needs to be highlighted in our discussion is that there are so many different rules governing accreditation schemes that they are of little use when trying to determine if organizations are genuinely environmentally friendly. For example, until recently, green winemaking simply meant organic where the use of synthetic chemicals were limited but now it has evolved to include the vague term of sustainable viticulture which might include carbon offsetting, saving water, or training staff. It is clear that the industry or policy makers need to develop a common language around what sustainable or green encompasses. Conclusion Clearly, many challenges complicate organizational and individual efforts to incorporate practices of ecological sustainability; however, sufficient examples exist to inspire leaders and organizational developers to continue pressing for change. The environmental practices of SMEs in general and wine producers specifically are still an emerging field of enquiry; yet an important one. In response to this need for research, we offer that environmental practices are driven by three important considerations, ‘business performance’, ‘regulation’, and ‘personal perspectives’ and moderated by two others – ‘organizational slack’ and ‘age’. It has been said that a person has two reasons for doing something – a good reason and a real one. In response to our question on what motivates organizations or individuals to adopt environmental practices, it would appear there are three good reasons for going green, a business one, a forced or adopted one (regulation) and a personal one. Which one is an individual’s real reason is, for the moment, still open for discussion. References Aram, J. (1989). Attitudes and Behaviors of Informal Investors toward Early-Stage Investments, Technology-Based Ventures, and Co-investors, Journal of Business Venturing. Sept. 1989, vol. 4, no. 5, 333-348. Arlow, P., Gannon, M.J. (1982). Social Responsiveness, Corporate Structure, and Economic Performance, The Academy of Management Review, vol. 7, no. 2, 235-237. Bakan, J. (2004). The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, Viking, Toronto. Bansal, P. Roth, K. (2000). Why companies go green: A model of ecological responsiveness, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 43, no. 4, 717-748. Berry, M. Rondinelli, D. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental management: a new industrial revolution, Academy of Management Executive, vol. 2, no. 12, 1-13. Beverage World (2007). Market Metrics: Going Green, October 15, vol. 126, iss. 1779, 20. Bianchi, R. and Noci, G, (1998). Greening SME’s competitiveness, Small Business Economics, vol. 11, no. 3, 269-282. Canadian Business for Social Responsibility (2001). Government and corporate social responsibility: an overview of selected Canadian, European and International practices, Canadian Business for Social Responsibility, Vancouver, available at: www.cbsr.ca. Crilly, D., Schneider, S. and Zollo, M. (2008). Psychological antecedents to socially responsible behavior, European Management Review, vol. 5, no. 3, 175 – 191. Dillon, P.W., and Fischer, K. (1992). Environmental Management in Corporations. Medford, MA: Tufts University Center for Environmental Management. Dutton, J.E., Jackson, S.E. (1987). Categorizing Strategic Issues: Links to Organizational Action, The Academy of Management Review, vol. 12, iss. 1, 76-91. Fletcher, I. (2001). A Small Business Perspective on Regulation in the UK, Institute of Economic Affairs, June. Geiser, K. and Crul, M. (1996). Greening of Small and Medium-sized Firms: Government, Industry and NGO Initiatives, in P. Groenwegan, K. Kischer, E. Jenkins and Schot, J. (eds.) The Greening of Industry Resource Guide and Bibliography (Island Press, Washington). Ginsberg, A., Venkatraman, V. (1992). Investing in new information technology: the role of competitive posture and issue diagnosis, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 13, iss. 37, 17. Gladwin, T. (1993). The Meaning of Greening: A Plea for Organisational Theory, in Fischer, K., and Schot, J. (eds.) Environmental Strategies for Industry (Island Press, Washington). Frantz, M. (2008). Green in the Glass, Restaurant Hospitality, April 2008, vol. 92, iss. 4, 76. Hoffman, A., and Ventresca, M.J. (1999). The institutional framing of policy debates: Economics versus the environment, The American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 42, iss. 8, 1368-1393. Jackson, S.E., and Dutton, J.E. (1988). Discerning Threats and Opportunities, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 33, iss. 3, 370-348. Lawrence, A.T. and Morell, D. (1995). Leading-edge environmental management: Motivation, opportunity, resources, and processes, in Collins, D. and Starik, M. (eds.), Research in corporate social performance and policy, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, 99-126. L'Etang, J. (1995). Ethical corporate social responsibility: a framework for managers, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 14, 125-32. Marshall, R. Cordano, M., and Silverman, M. (2005). Exploring individual and institutional drivers of proactive environmentalism in the US Wine industry, Business Strategy and the Environment, vol. 14, no. 2, 92 – 110. Marketing News (2008). Ask Dad to Pass the Green, October 15, 5. Mescon T. Tilso D. (1987). Corporate Philanthropy: A Strategic Approach to the BottomLine, California Management Review, vol. 29, iss. 2, 49-62. Nattrass, B. and Altomare, M. (2002). Dancing with the Tiger: Learning Sustainability Step by Step, New Society Publishers, Gabriola. Rivera-Camino, J. (2007). Re-evaluating green marketing strategy: a stakeholder perspective, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 41, no. 11/12, 1328. Sharma, S. (2000). Managerial interpretations and organizational context as predictors of corporate choice of environmental strategy, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 43, no. 4, 681-97. Utting, P. (2005). "Corporate responsibility and the movement of business", Development in Practice, vol. 15, no 3/4. Western Farm Press (2008). Wine Industry Intent on Truly Going Green, Oct. 4, Vol. 30, iss. 122, 21. Westley, F, Vredenburg, H. (1991). Strategic Bridging: The Collaboration between Environmentalists and Business in the Marketing of Green Products, The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, vol. 27, iss. 1, 65-91. Willard, B. (2005). The Next Sustainability Wave: Building Boardroom Buy-in, New Society Publishers, Gabriola. Williamson, D., Lynch-Wood, G. and Ramsay, J. (2006). Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 67, no. 3, 317. Zadek, S. (2006). The logic of collaborative governance: corporate responsibility, accountability, and the social contract, Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative working paper, No. 17, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Appendix 1 The Ontario Wine Industry at a Glance The wine industry in Ontario is clustered around four geographical areas. These are: • The Niagara Peninsula • Lake Erie North Shore and Pelee Island • Prince Edward County • Toronto. The Wine Council of Ontario has 65 members representing 75 winery properties. There are 497 growers in Ontario, covering 17,102 acres. Vintners Quality Assurance (VQA) sales have increased from $5 million in 1990 to $130 million in 2006. In 2006, there were approximately 750,000 visitors to wineries, and 6,000 jobs in the industry. The vision for the Ontario wine industry is that it will be a “thriving $1.5 billion business in 2020, one that employs 13,500 people and provides close to $1 billion annually in benefits to the province’s economy.” The industry is actively pursuing further expansion. From: Sustainable Winemaking in Ontario: An Environmental Charter for the Wine Industry (2007).