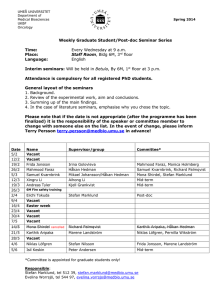

The Monologist - WordPress.com

advertisement