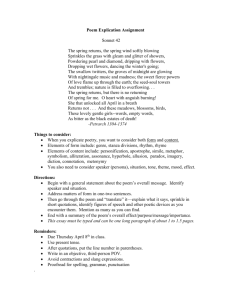

poemmovie task

advertisement

Year 11 English Studies 1 Text Analysis Oral Task Heinemann poetry 2: oral commentary and the creation of a digital photo-poem You must choose a poem from Heinemann poetry 2 – a different one from other members of the class – to prepare an audiovisual presentation of it (a digital photo-poem), followed by a commentary which presents an explanation of your digital photo-poem, along with an appropriate and well-argued interpretation of the poem upon which it is based. The total time should be 5 minutes, including the digital photo-poem (maximum 2 min.). Commentary – MATTER (< 5 min.) SACE Assessment Design Criteria – Knowledge and Understanding (2 & 3) and Analysis(2): The content of your commentary should cover a clear articulation of the poem's situation; identify its theme or general meaning (ideas and feelings expressed); be able to trace the development of the theme through the stages of the poem (eg. Each verse of Heaney 's “ Digging” builds on the previous one's treatment of the speaker's memories of his father and grandfather, enriched by images of the dignity of labour and linked by the title’s burgeoning metaphor); describe the voice or occasionally voices that the poet gives the speaker and why (eg. Plath’s “The Applicant” relies heavily on the language and tone of both a bureaucrat and a salesman to express her critique of modern marriage); explain how the poem’s style contributes to all or most of the above. Style* is really the use and synthesis of any number of techniques for getting meaning across to readers in the most effective way. The following list covers the most common poetic techniques, which can be used in any number of combinations and emphases DEPENDING ON WHAT BEST EXPRESSES A POEM'S MEANING. Rhythm Tone of voice Rhyme Atmosphere and mood Alliteration Punning Repetition Pattern Emphasis and surprise, breaking the pattern Juxtaposition of images Metaphor, simile, metonymy, paradox and other forms of figurative language *Refer to the Poetry Review booklet and this handout’s appendix with my model commentary on Bruce Dawe’s “After You, Gary Cooper”. Commentary – METHOD SACE Assessment Design Criteria – Application (2): This is generally up to you, BUT I recommend a brief general introduction to your “digital photo-poem” that will give the audience some basic information to engage their interest (eg. Title, author and why you chose it - but being “short” or having “crib notes on it” will not impress). After showing the digital photo-poem itself, you should try to deliver a well-structured argument that persuades the audience to accept your reading or interpretation of the poem. For this you will probably need to construct a short essay that could follow the features of the Matter outlined above. HOWEVER, you must incorporate a discussion of style into the main issues and theme of the poem. For example, if the theme of “The Sun Rising” is the all encompassing nature of sexual love, and its particular use of metaphysical conceits is a key issue, then specific examples of metaphors, hyperbole, rhyme, etc. need to be used in support of this view as you explain how the theme is developed from a particular situation, speaker, and tone. DO NOT LIST THEM AS IF CHECKING OFF A SHOPPING LIST! Commentary – MANNER SACE Assessment Design Criteria – Communication (1): Your commentary should be delivered in a clear, articulate and interesting way that directly engages the audience (standing up and making eye contact being the most obvious techniques for achieving the latter). Digital photo-poem (< 2 min.) SACE Assessment Design Criteria – Knowledge and Understanding (1), Application (1) and Communication (2): The digital photo-poem should reflect the sound and meaning of the poem by how well you create the drama, rhythm and sense of the poetic lines in your reading, as well as your choice of music, images and editing. REMEMBER to follow punctuation and the rhythm of the words, NOT line endings when pausing or changing the pace of your reading. Your tone of voice should also reflect the tone of the poem, although sometimes the speaker's tone may be different from that of the author / poem (eg. The Duke in “My Last Duchess” is disapproving of his ex-wife but the poem is not). The ideas, values and beliefs explored in the poem must also be clearly and imaginatively represented by appropriate images and music. The appropriate style and structure of a digital photo-poem is one that uses such images, editing and music to audio visually enhance the original poem’s form and meaning in a clear and effective way. 1 10% of Semester 2 SACE assessment Form and Meaning The real ideas of a poem are not those that occur to the poet before he writes his poem, but rather those that appear in his work afterward, whether by design or by accident. Content stems from form, and not vice versa. Every form produces its own idea, its own vision of the world. Form has meaning; and, what is more, in the realm of art only form possesses meaning. The meaning of a poem does not lie in what the poet wanted to say, but in what the poem actually says. What we think we are saying and what we are really saying are two quite different things. Octavio Paz From Alternating Current, translated from the Spanish by Helen R Lane, Wildwood House, 1974 Using Photo Story 3 for Windows: (free downloadable software from Microsoft for Windows XP computers; available in P1.19 from the START menu via “Other Programs” and “Visual Editors”) Open the program and click on the appropriate option such as Begin a new story. Press Next and you will find yourself in Import and arrange your pictures. Import your pictures from the folder where you have stored them. (It’s a good idea to have organised all the pictures you want to use in your project beforehand and placed them in a separate folder, but you can always import more at a later stage.) Click and drag the pictures into the order you wish them to appear. At this stage you can also remove black borders around your photos or edit them or leave that till later – it might not be necessary. Press Next and move into the Add a title to your pictures mode. Now you can place titles on any of the pictures. Try different fonts, different colours and different positions on the screen. You may also like to use different effects on the slides, such as Coloured Pencil, or Sepia. When you are happy with your titles, press Next. Now you can narrate your story and customise the motion on the screen. It is useful to type what you are going to say into the box to read from as you record it, or cut and paste it in if you have already written your script before you started. Speak clearly and loudly into the microphone. Check on the sound quality by pressing Preview. If you wish to redo it, Press the Delete Narration button and record again. The default length of time for a slide is 5 seconds, but if you speak for longer than this it will adjust, and if you wish it to be shorter or longer then click on Customize Motion and then Number of seconds to display the picture and make the adjustment. When you have finished recording your narration on each slide as desired press Next. You may now choose to Add background music. Just go to Select Music and import it from the folder where you have kept it. Alternatively you could click on Create Music and use the music they already have in the program. If, after previewing the project you don’t like it, then press Delete Music and find some alternative music. Check that the volume in the background music is quite low or it will be hard to hear your narration. Remember that if you wish to revisit any earlier stage in your construction of your project, just press Back until you are at your desired stage. An alternative to recording your narration separately on every slide is to prerecord your narration and mix it with some background music using a program like Audacity (free downloadable software). Then just import this file as your background music and adjust the length of your slides to fit your narration by going back to the Customise motion stage of the program. Once you have previewed your project and are completely happy with it, Save your story for playback on your computer. Specify its file name (the poem’s title) and location (in your home directory on the J drive) in then press Save Movie. The movie making process at the end of this may take some time, depending on the length of your movie and size of files (images, sounds, etc.) that you have used. If this last process is not followed, you will NOT be able to play your film on any other computer, even if you have been conscientiously saving your project as you have worked on it. This merely saves your project as a PS (photo story) file which is NOT a video format. Play your project using Windows Media Player and enjoy! Adapted from an assignment using Photo Story 3 designed by A.M. Robertson, Wilderness School After You, Gary Cooper… One of the main things I would say (off-hand, of course) about this awkward proposition known as Life, is that it can be a bit of a bastard if you don't happen to have the basic formula for facing it ready to hand – packed on the hip, butt out, with trigger tied back like a Colt forty-five – and your insurance premiums paid up. Particularly since Life, that taciturn hero with the steel-blue eye, though certainly not chain-lightening on the draw, can usually overcome what bystanders, if safely out of earshot, might call a marked deficiency by pumping an awful lot of hot lead in your general direction once he does clear leather. Personally, I'm damn glad I won't ever be any closer To the old Wild West than Ranch Night at the local theatre, because I'd a hell of a lot sooner let Life have it where it'll do most good from around the nearest corner, than parade the dusty Main Street of some anonymous cow-town, taking a long shade of odds on a one-way trip to Boot Hill, just for the sake of looking good for twenty gunsmoke-glorious seconds… Bruce Dawe After You, Gary Cooper… A model commentary The central conceit of this poem is to imagine life as a confrontation, in the metaphorical terms of a Wild West shootout. As the title suggests, its speaker prefers to offer the dubious glory of living one’s life as a hero to someone else, specifically a Hollywood actor, whose name invokes an allusion to High Noon, his most famous cowboy role as the reluctant amateur sheriff saving a community of worthless townsfolk. 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 INTRODUCTION The form of the poem is a kind of meditative rather than dramatic monologue, reinforced by the speaker’s conversational working out of an idea – namely, that “life … can be a bit of a bastard”. Dawe maintains this casual, man-in-the-street philosophising through the use of parenthetic phrases like “off-hand, of course”, or such informal expressions as “Personally, I’m damn glad…” The effect of this mode of address to the reader is to reinforce the speaker’s attitude of knowing reticence, a tone which supports his central idea that its better to hang back and avoid risks than speak up in bold declarative statements in the face of “an awful lot of hot lead”. Dawe’s use of diction skilfully combines a plethora of references to the culture of Hollywood westerns – “Main Street’; “Boot Hill”; “Colt forty-five” – with the self-effacing slang of an Australian idiom – “a long shade of odds”; “safely out of earshot”; “a bit of a bastard” – as well as the more contemporary language of our risk conscious urban world – “the basic formula”; “insurance premiums”; “a marked deficiency”. The poem’s success in fact lies in the way Dawe has managed to integrate these three different language types into a single voice, while still taking advantage of their unique qualities. The laconic Australian slang punctuates with irony what are in fact three quite long-winded sentences, setting off not only the intellectual tone of “this awkward proposition” but also the inflated Hollywood machismo of “packed on the hip, butt out, with trigger tied back like a Colt forty-five”. The latter metaphor(mula) beautifully expresses this also through its punchy rhythm and coarse alliterative monosyllables that almost cry out for an American cowboy’s accent. But this macho rhythmic pattern doesn’t awkwardly intrude, despite the use of hyphenated punctuation to insert it in the sentence. Its alliteration is prepared for in the more elongated phrasing that precedes it, with the blend of repeated ‘b’, ‘h’ and ‘f’ sounds. EXPOSITION The use of imagery, like the poem’s rhythm and diction, is smoothly incorporated into the speaker’s overall argument that life is a little more complex and risky than a Hollywood western. Personifying Life as “that taciturn hero with the steel-blue eye” and characterising its ‘solution’ as a metaphorical gunslinger’s trusty weapon, Dawe suggests that representations of life as a heroic confrontation between the individual and fate are dangerous oversimplifications. Even the ironic qualification of the ‘hero’ as something less than mythical in his prowess – “certainly not chain-lightning on the draw” – deftly marries the proverbial notion of life’s tediousness with its ability to surprise “once he does clear leather”. The final stanza picks up the extended metaphor of the traditional “dusty Main Street” shoot out, while reminding us that it comes from Hollywood stereotypes – “Ranch Night at the local theatre”. Although the speaker clearly emphasizes an ironic desire for anonymity, preferring to take life “from around the nearest corner” rather than on “parade”, two statements seem to bear the fuller weight of the poem’s impact. His intention to “let Life have it where it’ll do most good” is immediately followed by the corner reference, implying that the “most good” in life is to be found around it, not in the Main Street. But the proper sense of the sentence is that the “most good” refers to where Life ‘gets it’, not where we are when we ‘dish it out’. However, the ambiguity is surely intentional and the best interpretation seems to be that we won’t find the most good in life by imitating Hollywood stereotypes of heroism. The poem’s final line reinforces this with its implication of short-lived fame and vanity, where “for the sake of looking good” life is reduced to “twenty gunsmoke-glorious seconds…” imagery = key poetic terms monologue = other important technical terms CONCLUSION