Peace Conference exercise K - answers.doc

advertisement

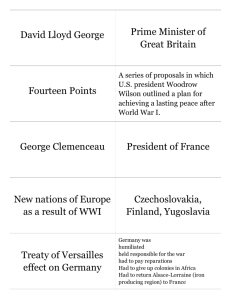

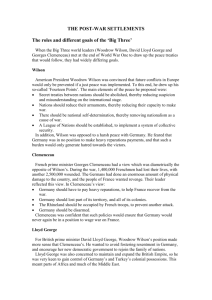

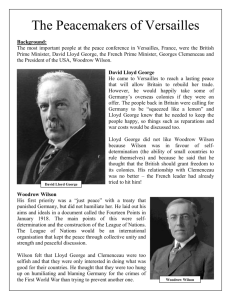

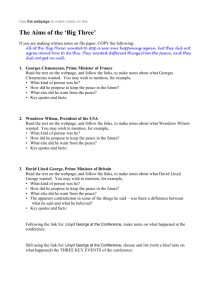

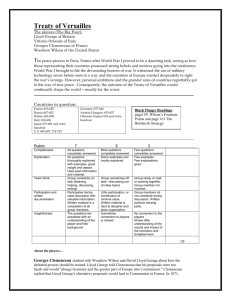

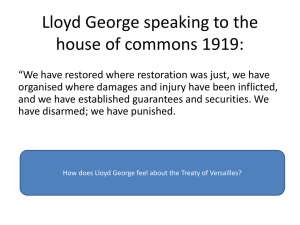

THE PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE DOCUMENTS EXERCISE K Use sources A, B and C and your own knowledge. How successful were Clemenceau, Wilson Lloyd George and in achieving their goals at the Paris Peace Conference? The ‘Big Three’ – Georges Clemenceau, Woodrow Wilson and David Lloyd George – came to the Paris Peace Conference with completely different ideas of how peace should be made with Germany. Those views were influenced by the circumstances of their respective nations. For France, the cost of the war was enormous, in both men and materiel. Not surprisingly, the French government went to the Conference seeking revenge and restitution. Prime Minister Clemenceau believed the Germans had forfeited any right to conciliation; France would simply dictate the terms of the peace. (Source A). Those terms were based on three key demands: that Germany be dismembered, losing land, population and industry; that she be made to pay the cost of the war to France; and that she be prohibited from possessing an army. These demands, Clemenceau felt, would prevent Germany from ever again threatening its neighbours. Unlike France, the United States emerged from the war almost unscathed. Its leader, Woodrow Wilson, could therefore afford to take a magnanimous approach to the postwar settlement. Wilson went to Paris determined that the peace with Germany be just. By rejecting the notion of punishment, he hoped that Germany might be wooed back into the community of nations. As he put it in a speech in January 1918, “We wish her [Germany] only to accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world – the new world in which we now live – instead of a place of mastery.” (Source C). This approach was based on the Fourteen Points he had proclaimed in 1918. The most important of these points, in Wilson’s view, were the renunciation of secret treaties, the reduction of armed forces, the right to national self-determination, and the creation of a League of Nations. Not surprisingly, Wilson was totally opposed to the notion of war reparations – a view which put him at odds with Clemenceau. The position British prime minister David Lloyd George brought to the Conference was somewhere between that of Clemenceau and that of Wilson. While he agreed with many of Wilson’s Fourteen Points, he was constrained by the strength of public opinion at home. Like France, Britain had suffered heavily during the war, and its people believed that Germany should be made to pay a price for this. Lloyd George found himself siding with Clemenceau on this point. In the end, all three leaders got much of what they wanted at the Conference. Wilson got the League of Nations, as well as a commitment to the principle of national self-determination. (Source B). Lloyd George got the reparations his people were demanding, while Clemenceau got agreement on the dismemberment and disarmament of Germany. Germany was to lose all of her colonies, 12.5 percent of her territory, 7 million of her people, all of her foreign investments, and was required to pay US$32 billion in reparations. In addition, the German army was to be limited to 100,000 men, with no aircraft, tanks or heavy artillery. In many ways, the big winner at the Conference was Clemenceau, since virtually all of his demands were met. The loser was Wilson, who had to settle for a harsh peace. Nevertheless, he did manage to reduced the level of reparations from US$200 billion (as demanded by the French) to a ‘mere’ US$32 billion. Assess how useful Sources C and D would be for an historian studying the Allies’ approaches to Germany at the Paris Peace Conference. In your answer, consider the perspectives provided by the two sources, and their reliability. Sources C and D are both useful to an historian studying the Allies’ approaches to Germany at the Paris Peace Conference. Source C is an excerpt from an address by American President Woodrow Wilson, delivered to a Joint Session of Congress in January 1918. In this speech, Wilson set out the American perspective on peace with Germany and its allies – the so-called Fourteen Points. In his view, the best way to ensure world peace was to offer Germany a just settlement following her defeat – one based on reconciliation rather than retribution. In Wilson’s words, the only thing the United States wished of Germany was for her to “accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world…instead of a place of mastery.” The US position was consistent with the liberal principles which underpinned America’s own system of government. Sadly for Germany, Wilson’s allies did not share these lofty ideals. They were more interested in the practical matter of punishing Germany and making her pay for the war. France, in particular, was determined to strip Germany of territory and resources, in order to render it militarily impotent. Britain concurred with this approach, although its prime minister, Lloyd George, had some personal doubts. The severity of the peace imposed on Germany is well illustrated in Source D, a note from the German government to the Allies in June 1919. In this memo, the government protested at the “unworkability” of the conditions imposed by the Treaty. With its territories and population reduced, Germany lacked the resources to meet the level of reparations demanded. The government also objected strongly to the inclusion of Article 231, which placed responsibility for the war solely at Germany’s feet. Nevertheless, the perspective of this document is not entirely blinkered. The government did not reject the right of the Allies to impose a peace of their choosing, and accepted Germany’s obligation to fulfil the conditions of that peace. Both documents are very reliable historical sources. Wilson’s speech set out the position he took to the Conference, although he did wind up compromising his principles somewhat in order to reach an agreement with Britain and France. (He accepted the need for reparations, and for Germany to be partly dismembered.) Source D shows how seriously the Germans regarded the conditions imposed upon their country. This is borne out by the level of reparations demanded by the French at the outset of proceedings – US$200 billion. Even the amount finally agreed upon – US$36 billion – was crippling for a nation devastated by war.