figure 01: channel migration strategies

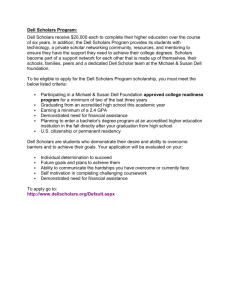

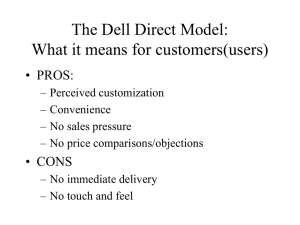

advertisement

30 words summary “The emergence of a new distribution channel will always cause disruption and shift in the marketplace. Before switching over from the old to the new managers should assess how the new channel will affect their companies existing channels, customers and competitors,” says the leading professor of marketing from the London Business School. 100 words summary When a new distribution channel emerges, managers must ask two essential questions: To what extent does the new channel complement or replace existing industry distribution channels? To what extent does the new channel enhance or devalue our existing capabilities and value network? The answers to the above questions should help pinpoint the necessary channel migration strategy, the level of internal resistance, and the external channel conflict that one should anticipate, as well as provide insight into the migration process. Keywords: Nirmalya Kumar, marketing, distribution, channels, customers, competitors, strategy, migration, information technology, personal computers, retail Authors Summary: Nirmalya Kumar, Director, Centre for Marketing, and Director, Aditya V Birla India Centre, London Business School Chart: figure 01: channel migration strategies figure 02: value curves: dell direct versus retail channel transitions in the pc industry by Nirmalya Kumar The emergence of a new distribution channel will always cause disruption and shift in the marketplace. Before switching over from the old to the new, managers should assess how the new channel will affect their company’s existing channels, customers and competitors. When a new distribution channel emerges, managers must ask two essential questions: To what extent does the new channel complement or replace existing industry distribution channels? To what extent does the new channel enhance or devalue our existing capabilities and value network? The answers to the above questions should help pinpoint the necessary channel migration strategy, the level of internal resistance, and the external channel conflict that one should anticipate, as well as provide insight into the migration process (see Figure 01). replacement versus complementary effects Supermarkets that displaced 'mom-and-pop' stores in the US illustrate the replacement effects of new distribution channels. The supermarkets' value proposition of a better assortment, one-stop shopping, and substantially lower prices surpassed that of the stores. Consequently, the absolute number of mom-and-pops and their relative market share declined. In contrast, television and home video extended the distribution channels of the motion picture industry. When television first appeared in the 1950s, Hollywood studio market values fell dramatically. The same happened with cinema companies when home video first appeared. In each instance, managers and analysts overlooked two important issues. First, the value proposition of the new distribution channel was different from, but not superior to, the existing channel. Home video, for example, offers greater assortment, time flexibility, informality, and lower prices, whereas cinemas are venues for a "date" or "an evening out." The two distribution channels have clearly delineated value propositions for distinct customer usage segments and can therefore coexist. Second, home video allowed consumers to watch movies when homebound by babies or illness or when cinemas were closed or no longer running a particular film. Television and video expanded the market for motion pictures and provided substantial additional streams of revenues for the industry. For example, in 2002, US box office revenues were $10.1bn, but combined sales and rental of VHS tapes and DVD discs exceeded $25bn. Whether a new distribution channel complements or displaces existing distribution channels highlights the nature of channel migration. In replacements, the existing customer segments buy from the new channels of distribution and abandon the existing channels. In contrast, complementary distribution channels open up new segments of customers or new value propositions for existing products. Cannibalization, channel conflict, and resistance to change occur more in replacement situations. Replacement channels force incumbents to abandon existing channels and focus on new channels of distribution. The ability to purchase airline tickets or book hotel and car reservations over the Internet will not likely increase the number of vacations or business trips consumed. Instead, with the necessary information accessible online, many customers will simply not need a travel agent. Replacement effects also obligate managers to determine which channels and segments are affected. For example, leisure consumers for airline travel are migrating faster to Internet channels than business travelers. Based on the firm's competitive position in each segment, one may decide to accelerate the migration, as easyJet does by offering discounts to customers who book on the Web, or decelerate by refusing to accommodate the new channel. In contrast, complementary effects compel companies to move certain types of transactions and customers to the new channel of distribution. New channels add to the existing value network without lowering the value of existing distribution outlets. Marketers must communicate these economics to distribution members. Sharing independent market research demonstrating the complementary effects works well in reducing channel member anxiety. turning core capabilities into core rigidities The emergence of a new type of distribution channel usually generates considerable excitement as companies see the potential for increased coverage, lowered costs, and/or greater control. Unfortunately, innovative new distribution channels also aggravate industry incumbents. Established companies often fear radically new distribution channels will harm them by obsolescing competences, devaluing their distribution network assets, ossifying their core capabilities, and eroding their industry leadership positions. To illustrate these repercussions, let us examine the channel transitions in the PC industry. channel migration in the pc industry In 1981, almost 80% of personal computer sales were through a combination of a direct sales force serving the large accounts and full service PC dealers reaching the rest. Currently, direct sales and PC dealer account for less than 40% of the industry sales with the remainder flowing through a multiplicity of channels including value added resellers (VARs), direct response pioneered by Dell, mass merchandisers dominated by Wal-Mart, warehouse clubs like Price Club/Costco, consumer electronic superstores populated by Best Buy and Circuit City, computer superstores led by CompUSA, and office product superstores such as Staples. In addition, there are numerous Internet operations of brick-and mortar and pure play retailers. During the intervening years, channel transitions have played a major role in determining the changing fortunes of PC manufacturers such as Compaq, Dell, and IBM. compaq versus dell Today, the worldwide PC market leaders are Compaq and Dell. However, the business models of the two companies differ significantly. Compaq has a value network typical of branded products: relatively high R&D expenditures; low cost, low variety, large run manufacturing systems; one month finished products inventory; and third-party resellers. In the early 1990s when IBM, with its large direct sales force, was ambivalent about third party resellers, Compaq dedicated itself to PC sales through resellers whose subsequent push catapulted Compaq into market leadership in 1992. Dell primarily targeted corporate accounts but with built to order, customized PCs at reasonable prices. It invented a radically different value network combining minimal R&D expenditures, made-to-order, flexible manufacturing systems one week parts inventory, and an efficient direct distribution system. In the early 1990s, this distribution system took orders through toll free telephone numbers and delivered through various courier services. dell's retail experience As the value curves in Figure 02 indicate, the value proposition of serving customers through Dell Direct differs from that through retail stores. In 1991, to reach those small business customers and individual consumers who preferred to shop at retail outlets, Dell decided to expand its distribution to retailers such as Business Depot in Canada; CompUSA, Sam's Club, and Staples in the US and Mexico; and PC World in the UK. However, unlike the customization option available through the Dell Direct channel, since selling through retail stores required Dell to build for inventory, only a limited number of preset PC configurations could be offered in the indirect channel. Despite this limitation, channel expansion to retail stores brought immediate and impressive sales gains for Dell and revenues rose to more than $2.8bn in 1993. Unfortunately, the sales gains through the retail channels did not result in additional profits. Dell's internal cost of selling fell from 14% in the direct channel to 10% in the indirect channel as retailers took responsibility for some channel functions. However, this did not fully offset the 12% margin that retailers had to be given for their sales efforts. As a result, it was 8% percent more expensive for Dell to sell through indirect channels. Given that its operating income was only 5% in the Dell Direct channel, it was losing 3% in the indirect channels. And the more volume Dell pushed through the retail channels, the more money it lost. In 1993, Dell posted its first loss of $36mn. By mid-1994, Dell decided to exit the retail channel and concentrate on direct distribution. This decision turned profits around to $149mn in 1994. Beyond the economics, Dell sidelined many of its core capabilities and advantages when sales went through retail. Michael Dell explained, "Our direct model turns inventory twelve times, while our competitors who sell through retail only turn their inventory six times. Even though customization increases our costs by 5%, we get a 15% price premium because of the upgrades and added features. But for the standard configurations we offered through retail, we (could not) get any premium in the market." New channels may help some companies leverage their core competences and distribution assets, while it hinders other companies within the same industry. How competences and assets are affected depends on how a company competes within an industry. But the need to develop new capabilities usually generates considerable internal resistance as it devalues the power of those within the organization who run the existing value network. Abstract from Marketing As Strategy written by Nirmalya Kumar