Ants - Cambridge Community Television

“Ants” or

“Ants and Humans” or

“Myrmecos” or

“The Fantabulous Ant Movie with a title yet to be determined”

Script, Version 1

6/11/07

Corrie Moreau: Humans are thought to be about, uh, a quarter of a million years old, like two hundred and fifty thousand years . (w/i 0.0.59.0 to 0.1.13.0)

<shoot sidewalk or ground at foot-level, try to get people’s bodies in long distance, people’s feet in medium distance, some blurry objects in extreme foreground are out of focus and not recognizable>

Corrie Moreau: Ants are about a hundred and forty to a hundred and sixty-eight million years, so ants have been around for a very long time. (w/i 0.0.59.0 to 0.1.13.0)

<we rack-focus to see ants crawling around in the extreme foreground>

<possibly superimpose a simple animation of two lines: one near the top showing how long humans have existed, the other, near the bottom, showing how long ants have existed. The bottom line would be at least 500x the length of the top line, so we’d modify the scale as the lines grew. Or perhaps have one line that represents human existence, and then a much longer line, that represents ant existence, grows around and envelopes that line to show the scale.

Kari Ryder-Wilkie: There’s many, many, undescribed species of ants. Um, I think that the number of described species is somewhere around 12,000 right now, worldwide, but there’s absolutely, definitely more.

(laughter) . (0.9.15.11 to 0.9.32.0)

<one after another, couple of seconds of footage of different types of ants, maybe with their name and Latin name in lower-thirds. Could use Amy Mertl’s Ecuador B-roll for this. Could also include photographs, drawings from history, of different ants>

Stefan Cover: I mean, there have to be at least a hundred billion ants on the planet. [That’s] conservative. But, uh, G-, Lord knows what the actual figure is. (w/i 0.13.47.0 to 0.14.1.0) (sound cutout on That’s)

<show large groups of ants: the army ants, the leafcutters.>

Corrie Moreau: unless people are out looking for ants in their natural environment, the only time they encounter them is when they come in their house, or at their picnic. (w/i 0.18.10.0 to 0.18.44.0)

Kari Ryder-Wilkie: …they think of them as pests, or, you know, things that get into their kitchen, that they want to get rid of. (laughter, which could play underneath the movie clips and eventually fade into their audio)

(0.37.54.0 to 0.38.6.0)

<clips from that movie that was an ad for insecticide, clips from “Them!”, maybe one where people are panicking or screaming, in the middle of screaming we would abruptly cut to Stefan>

Stefan Cover: You say, well, you study ants, and they look at you as if you’ve, you’ve, you know, descended from Mars, or something like that. Like, “Oh my God, what would be the point of doing something like that?”

(w/i 0.14.6.0 to 0.14.33.0)

<title on screen (with Rob’s graphics) then start with the first section>

< black screen>

Stefan 0.6.51 – 0:7:46: ) Well, the truth of it is, it was, it was boredom.

< fade in to b/w shot of new york city, fade to Stefan during school as form of incarceration >

I was a kid—I grew up in New York City, I, and, um, you know, I viewed school as a form of incarceration, and, uh, so I would pray to the gods, you know, uh, all school year, (inhales, closes his eyes like in prayer) ththat summer vacation would get here.

< Broll of Stefan at museum or collecting to cover transition, then back to interview>

but, you know, after two or three weeks, I’d done everything I knew how to do…I got so bored that I started watching ants. You know, walking by the porch. And I’d, I’d drop crumbs in front of them and the ants would come, and I made the, the, uh, seminal discovery that if you put ants of two different kinds in a peanu-peanut butter jar, that they’ll start fighting. Well that was, (throws up arm) well, you know. I mean, I was off and running at that point.

(Add quote from Kari describing how she got interested in ants?)

Clip name: mario- termites; neurocorrelates of age and size ants

Timecode: 00:05:06:00-00:05:53:00

Content:

I knew that I wanted to work on social insects and when I came to Boston, I really enjoyed Boston, and my current advisor works on ants and he had a project in mind to look at the differences in behavior in ants and to look at the neurocorrelates. I said ‘”that sounds great’. I had never done any neurobiology before but I kind of jumped on board.

< transition with B-roll of ants covering Corrie’s statement >

Corrie 0.15.36 – 0.16.6: I can’t say what it was about ants in particular, I just always knew that I was drawn to the ants, more than any other insect, but I found them incredibly amazing, and they had so many diverse kinds of habitats and behaviors and… morphology and color ranges and they’re found in all these different, unique habitats

Megan 0.14.52 – 0.17.48: there’s actually a great study that was published in the 1970s,

< use shot of abstract of study to cover this part>

…some of the data was re-analyzed in, in the 1980s, um, by a professor, E.O. Wilson… and he, uh, showed that

< back to Megan > ants are actually, uh, four times the biomass of all of the terrestrial vertebrates in an Amazon rainforest put together. So that means if you went out to an area, and collected all the ants, and all of the terrestrial vertebrates, which includes all the mammals, so jaguars and monkeys and birds and, uh, reptiles and amphibians, the ants would actually weigh four times more than all the, um, these other things put together.

< we could make a snazzy graphic to demonstrate this is…>

<add some quote from Kari on the biodiversity of ants>

< Broll of Stefan or MCZ to cover next quote>

Stefan 0:4:9 – 0:4:35: I have the responsibility of, of caring for the world’s largest ant collection, of all things.

And, uh, there are about a million specimens, and it occupies one whole, large room. And I’m, um, my duties are, really, to maintain the collection, to im-improve its, uh, you know, how it’s kept, and to add to it.

< Broll from collecting trip during next statement from – shots of them driving in the car, concord sign)

Stefan 0.21.19 – 0.21.47: . So, you spend most of your time out collecting, see. There you are, out, out collecting, and, and, uh, um, lots of st-stories can be told about collecting.

< switch to collecting audio>

Ant collecting B Roll:

Stefan digs into another nest

S: Good looking nest

Zoom in to hands, aspirators sucking ants from dirt

< Stefan audio below starts during aspirating shot>

Stefan 0:22:8 – 0:22:36: …the way you collect ant specimens is, you know, you suck them up with a little aspirator, it’s sort of like a little, a little hand-, lung-powered vacuum cleaner,

Ant Collecting B-roll: 0:32:03 – 0.32.44 – digging up nest next to high way

Ant Collecting B-roll 0.55.04 – 0.55.35:

Stefan talking to people in a car

S: Why else would you be on the roadside digging holes?

People in car: Any good ants?

S:

Yeah, right here you’d never think so but yeah

P: God bless you Jesus loves you!

S: Thanks guys.

Stef bends down to look for ants while car drives away

Stef shovels hole

< fade in audio from next clip at the end of this segment, then switch to Stefan interview>

Stefan: 0.25.31 – 0.26.16: This is the kind of stuff that happens when you’re out looking for ants. You know,

(clears throat) people think it would be boring most of the time, and, you know, sometimes it, it may be. But, uh, but, there’s always, you know, weird things, um, that happen,

< clip from ANTZ here, fade to Corrie audio>

Corrie 0:19:13 – 0:20:42: So I think that Woody Allen was one of the main worker ants in a recent movie, and, and all ants, um, if you see them out foraging, or hunting, or carrying food back, or any of those things, they’re always all female. So ants are predominantly female-oriented societies, and males are only really made once a year.

Megan 0.8.45 – 0.10.54: The gender balance in the ant world is quite unique, because, really, all ants that you’re likely to see on a day-to-day basis are female. Um, and they have this unique, um, uh, sys-system for determining, um, the sex of an ant. It’s called haplo-diploidi , which is a very fancy word for something that’s actually quite simple.

< use microscope B-roll of ants with larva over Corries explaination>

Corrie: 0:27:05 – 0:28:07: : …all males come from an unfertilized egg, meaning that they’re haploid : they only have one set of chromosomes, where all females are the result of a fertilized egg, meaning that they’re diploid: they have two sets of chromosomes, like humans do. So when a queen ant is laying eggs, she essentially decides whether or not it’ll be a male or a female. And the way that she decides that, is whether or not she fertilizes that egg inside of her

< back to Corrie>

Corrie 0:19:13 – 0:20:42: So you wouldn’t ever have a male, uh, worker running around, alerting everyone and, and saving the day. It would always be the females. (laughs)

<Kari clip about Antman comic book, joke I think she made about males just being for sex?>

Corrie 0:19:13 – 0:20:42: So, males are really only there to reproduce with other winged queens, or at that point, virgin queens from other colonies. So, after they’re produced, they’re sort of pushed out of the nest: they’ve never helped clean or gather food or anything. And once they mate, they die relatively quickly. So most male ants, at the adult stage, are really only alive for about a week.

< maybe use some Broll of alates from leafcutter nest here>

Now the queens, once they’ve mated, they’ll store all of that sperm for all of the millions of eggs they’ll need throughout their life. And once they’ve mated, they’ll fly around and they’ll find a suitable habitat to start their colony, and using their legs, they’ll rip off their wings and then dig into the soil or under the tree bark or wherever they keep their colonies.

< Broll of ant queen under microscope>

Megan: 0.11.04 – 0.11.49: The queen ant is very important in an ant colony because she is the only ant who, um, can reproduce. Um, so she’s the only ant in the colony who lays eggs.

<if Mario says anything about the importance of the queen should include that here>

Ant Collecting B-roll: < can probably edit this section down a little> :

Mario and James dig up a nest

Close up on Mario’s face.

M: Shit.

J: Want to go one more? I mean one deeper?

Mario shovels out another scoop.

M:

There’s a major

J: Got something there

M: Like right under here?

J: Yeah there’s something there

Mario scoops out another shovel full

J:

Here’s a major a some brood, there was nothing right up on the top

M: Do you have the tray?

J: Want to dump it?

James dumps out dirt in tray, puts shovel full in

M: Oh there you are!

J: Oh there she is! There she is! Alright we need to get the rest of the colony now. Good eye.

M: Alright. Now I gotta get some brood.

Ant Collecting B-roll:

S: The thing about the queen is they have symbolic as well as actual importance, you know you get the queen it’s like you get the holy grail, oh boy it doesn’t get any better than this.

J:

Doesn’t matter how big the colony is

S:

No, you can get 10,000 workers and brood and…it’s not quite the same if you don’t have a queen.. well this great.

< fade in James audio before video>

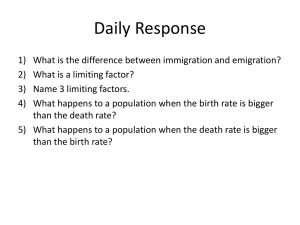

Clip name: mclurkin_ant communication

Timecode: 0.11.50.20 to 0.12.43.11

Content:

So, real ants use, um, lots of different ways to communicate with each other. Um, they use antennae, they come and rub each other with antennae <waves fingers on head to illustrate>

< Broll of ants under microscope touching each other with antennas> some ants can detect vibrations, some ants can detect, they, they can [indistinct] an area around them, but, some ants use vision, but their primary mode of communication, um, that’s common to all ants, is pheromone communications. So, they use chemicals.

<

Broll of army ants following trail over Megan’s audio, to cover breaks>

Megan 0.4.30 – 0.5.21: Um, ants can see visual cues, so they can see, but, um, many chemical cues are often stronger. So, um, they are very famous for leaving,…pheromones or chemical signals in which to mark trails, so that they, um, uh, “know” where to go out and forage, uh, to look for food.

< Broll of ants carrying dead caterpiller over this part (from collecting trip)>

Corrie: 0:8:48 – 0:10:49: So whenever you see ants out, um, foraging or looking for food, once they’ve subdued a prey item, such as a cricket or a grasshopper, you’ll often watch them carrying it all back to the nest. Well, the reason that they do this is that ants have a very tight constriction in their neck. They can’t swallow large, solid food items.

< Broll of ant larvae under microscope as she starts this >

Now, the larvae of ants essentially look like fly maggots: they’re a sack with a mouth. They don’t have that constriction yet in their neck. So once the larvae have ingested this prey item, if the workers, or the queen in particular, who’s laying eggs and needs a protein source to do so, needs a little of that protein, she’ll go over and she’ll (makes drumming gestures) drum on the larvae with her antennae, and this w-, signals to the larvae to regurgitate some of that protein source to the adults. So it’s sort of the opposite of what you see in birds, where the “baby” bird is, in fact, now regurgitating to the adult.

< Photo of amblypopone ant to cover break – Kari might have on her website>

Well, in the Amblyopone , or the Dracula ants, they don’t have this ability or this signal c-, or communication between the adults and the larvae…So in order to obtain some of that protein source, the adults and the, and the queen have to pierce the integument, or cuticle, of the larvae, and then lick up the exuding hemolymph or blood.

Now, this is considered non-destructive cannibalism, because it doesn’t seem to harm the larvae. The larvae will keep going through successive molts. And sometimes by the time they reach that last larval instar, they’ll be heavily scarred. So that’s where they got their common name, because they actually feed on the blood of their larvae. (laughs at reaction) .

< close up on Corrie’s tattoo of the amblyopone, show other tattoos as she talks >

Corrie: 0:14:23 – 0:14:53:…I think I got my first ant tattoo when I was about eighteen years old. I-I knew then I wanted to work on ants, and… slowly accumulated them through the years, but entomology or insect science and myrmecology, which is the study of ant biology, has always really fascinated me, and, and I’ve chosen to adorn my body with it as well.

< can use shot of tattoo to transition to Stefan’s audio>

Stefan 0.8.15: - 0.8.47: … myrmekos is Greek for “ant.” So, in, you know, in time-honored scientific tradition, you know, we’ve got to have an “ology,” and we have to have a, you know, a Greek or a Latin term, uh, you know, um, just like every, you know, every, every discipline is def-defined by those kind of terms. So myrmecology is basically the study of ants.

< Broll from MCZ, shots on walls of famous myrmecologists, use these or pictures of the individuals he mentions as transitions between the next three segments >

Stefan: 0:9:44 – 0:10:40…the actual s-, scientific study of ants really didn’t begin until, um, the 1700s and the

1800s. And the thing that first interested, uh, scientists about ants was of course their behavior, which is what, the first thing about ants that interests any-, that anyone.

Stefan: 0:11:27 – 0:12:30 A, a very famous one was the American myrmecologist, William Morton Wheeler, who was at, who was at Harvard. Uh, and, and, uhn, early in his career he did a lot of field work on ants in

Texas. And he went on to have an enormous, you know, uh, lengthy career, uh, highly successful, as a Harvard professor, and published, um, I mean, hundreds of papers on ant, uh, taxonomy, and also ant, um, behavior, and, uh, every aspect of ant biology.

… Bill Brown was a very famous ant systematist who m-modernized the classification of ants, and, uh, and then, um, Edward O. Wilson, uh, the two, the two, you know, modern biggies in the field, so to speak, are

Edward O. Wilson and Bert Hölldobbler, really, who, who, you know, have taken the study of ants righ-, you know, sort of into the twenty-first century, in terms of using modern techniques and things like that.

Stefan: 0.35.28 – 0.35.43: Certainly, it’s true that, uh, you know, one of the reasons why ants are so, in fact, perhaps the primary reason why ants are so fascinating to, to human beings is that they, uh, uhn, that they do, they do so many things that remind us of, of, uh, ourselves

Megan 0.18.4 – 0.18.54: It’s really hard to know…it’s hard to compare ant societies and human societies in many ways

<Use quote from Kari or Mario on this type of comparison here?>

Corrie: 0:11:27 – 0:12:20: I’m not clear that you can take away any meaningful information. I mean, I-I-I know that, you know, in passages throughout history, people have said, “Oh, you know, go forward and work like the ant,” and, you know, “Be industrious,” and, or, you know, “The ants are always looking out for one another, and maybe we should try to live that way,” and, and I think that those sorts of, you know, bigger picture takehome messages, if, if you needed the analogy with ants to humans to, in order to do those things, then that’s great, but there are also situations where we could say, you know, “We should feed on our young, just as the ants do,” and I don’t think that that’s something we would want to extrapolate throughout, you know, across those species boundaries.

< Broll of ants and humans doing similar things as Stefan talks>

Stefan: 0.32.14 – 0.35.6: , it’s really important, it’s really important to realize that ant societies and human societies are fundamentally different. They’re, um, ants do things that are, uhn, that remind us of human

activities, but they, but they’re not doing things that are actually forms of human activity. (almost no pause – use Broll over transition to Megan )

Megan: 0.37.57 – 0.38.37 ants and human societies are similar in in some other ways at least… ants of course have a division of labor in the colony where um particular ants will specialize in particular tasks in order to uh be more efficient as a unit as a colony unit uh and human societies also divide labor and have people specialize in particular jobs in order to have the society function more efficiently

< Broll continues until next segment begins>

Megan: 0.7.8 – 0.8.31: …So all ants have a division of labor, between the queen, who, um, only lays eggs in the colony and is responsible for all of the reproduction, um, and the workers, who do all these other tasks: of going out and looking for food, and cleaning the nest and taking care of the young.

< Broll of ants, showing workers and soldiers>

Stefan: 0.51.41 – 0.52.3 Well in some ants, the workers are divided into two kinds: there are small workers that do most of the work, and then there are these large-headed, uh, workers called soldiers , uhn, which sometimes have a defensive function.

< Broll of soldier ant attacking smaller ant under microscope>

<ant warfare section begins – still needs B-ROLL, need to add quotes from Mario/Kari if applicable>

Stefan: 0.47.7 – 0.47.58 Now with, with ant warfare, ant warfare is a lot like, think Gladiator (laughs) . I mean, you know, I mean, you know, now that we’ve evolved so f-, so wonderfully far that we can shoot each other with missiles and stuff like that, I mean, you know, we, we kind of miss what warfare was like for most of human history. Which is to say, you had to h-, personally hack at your opponent with a sword or stick him with a spear or something like that. (no pause)

Well, ants are, have not, uhn, evolved, um, much in the way of long-range warfare yet. They still do it the old-fashioned way, which is to say that you have to fight with your opponent physically, and the main weapons, uh, that ants use in ant warfare are their mandibles, which are their, their, you know, colloquially we call them the jaws, they’re, which are in the front of the ant’s head, and usually sort of triangular, and have sev-, you know, um, several to many teeth on them and these are the ant’s universal tools.

(almost no pause)

Corrie: 0.20.56 – 0.21.21 Warfare in ants is, is different across every species that you look at. And not only is it different across other species, every species, but it’s also different depending on who they’re interacting with.

So some ants are very aggressive towards other ants of the same species, and you may have situations where neighboring colonies will actually fight for territory or space or food resources.

Megan:0.25.33 – 0.26.11 There are a huge range of different, um, types of, of, fighting behavior that ants engage in. Um, they, uh, some kinds of ants will, uh, grab on to other insects, um, other ants with their mandibles and then spray, uh, toxic chemicals at their enemies in order to, um, keep control of an area or to, uh, to win a battle over a food source. Um, uh, so ant warfare is actually a very, a very complex process.

Stefan: 0.36.38 – 0.38.10 Both human wars and ant wars are territorial, um, but, um, you know, can be territerritorial, in, in nature, but, uh, in ant wars, it’s, it’s colonies that are fighting each other for, um, uhn, mattermatters directly pertaining to their survival. They need a foraging territory, they can’t have a rival colony too close to theirs or they may starve, something like that. The, the wars are very utilitarian, um, uh, you know, slave making ants which fight wars against, uh, so-called “slave species” are fighting, are fighting that war because they need, not because they, you know, for any reason other than the fact that th-they want to get, they have to get the pupae from the slave species, or else they’ll, they won’t survive themselves.

Human beings, on the other hand, as, you know, I’m sure some of our wars are wars of survival, but often times, you know, with, you know, with our marvelous cult-cultural development, in a way, we’ve gotten, we’ve gotten a long way aways from the biology, and we fight a lot of conflicts that really have nothing to do with survival at all, that have everything to do with, you know, um, you know, um, the insanity of political leaders, the, you know, the, the, uh, the, the gullibility of, uh, masses of people who can be incited to violence, and very easily, and, uh, it’s, you know, we’re, we’re in a different space now, because so much of our conflict really has nothing to do with survival. In fact, we’d all survive a lot better if we cut it out.

Stefan: 0.48.44 But most ant warfare is the good, old-fashioned slugging match, where you, you grapple with your opponent, you try to cut off his appendages, by-, and possibly his, her, her head and her rear end or whatever. It’s just, it’s just bloody gladiatorial combat, but, uh, it’s really funny, um, because, uh, certain ants have evolved ritual battles.

Corrie: 0.21.53 – 0.22.39 There are some ants that d-, exhibit very unusual behavior, so some ants in the desert, when they encounter one another, as most humans, you don’t really want to actually have a war, you don’t want to physically hurt each other if you don’t have to. It’s much more cost-effective to say, “I’m bigger than you.

You’re bigger than me. What are we going to do?”

So these ants do the same thing. So as they coun-, encounter each other in the desert, before they start actually tearing off each other’s legs, if you’re going to lose a whole bunch of workers from your colony, needlessly, you don’t want to do that. So what they’ll do is they’ll measure up to one another, and try to figure out who’s taller. And so then, if you’re bigger, you know you’re going to win the fight, and if you’re smaller, you run away. Well, in some ants, they’ll actually even stand on their tippy-toes, or even try to stand on close pebbles to seem taller than the ant that they’re about to battle. So you’re going to see all these interesting behaviors.

Stefan: 0.49.56 – 0.50.45 They’re, they’re, um, you know, they grab each other, but they don’t sting, they, but they go through the motions of stinging. They go through every-everything, they go through the motions of biting, but they don’t actually chop heads and appendages off. And so they have these huge battles and somehow they, the ants are able to assess the relative strength of the colony, each colony, and then they make, a decision is made. One colony gets the foraging area and the other colony retreats and then everybody goes home and you-, and there are no bodies laying around, or very few bodies. So it’s actually, y-you know, in some instances ants have ritual battles. (no pause)

You know, we would do well to imitate them, uh, because we seem to mostly have real battles.

<agriculture section begins – still needs more detailed B-Roll, quotes from Kari and Mario>

< Maybe use Broll to transition – go from a human army to army ants crossing clearing to pan of devil’s garden?)

Megan: 0.1.30 – 0.2.20: For the better part of the last two or three years I’ve been studying, uh, ants that make these very unusual gardens in the r-rainforests of the Amazon that are called “devil’s gardens.” Um, devil’s gardens are very strange places, because they are clearings, um, where only one or at most two species of tree grow, and these clearings occur in the middle of very diverse Amazonian rainforests, where usually there are hundreds of tree species growing together.

And they are called devil’s gardens by local people because local people believe that they’re cultivated by an evil forest spirit, and his name is supposed to be the, the Chuyachaqui . Um, but, in actual fact, I did, um, quite a bit of work to show that these gardens are cultivated by ants.

< Broll of “lemon ants” can be used for this section>

Megan: 0.28:50 – 0.29:34 So, the ants that live in, in devil’s gardens, uh, create these devil’s gardens by killing all kinds of plants that try to establish within the boundaries of their colony except for the tree species that they

live in. ….So the tree species that they live in is actually very special, because on the stems of this, of this tree,

…there are these, uh, hollow, swollen places that have a little hole…And the ants actually use these holes, uh, to nest in. And, uh, the tree will have many of these small holes with ants nesting in it.

Megan: 0.22.20 – 0.22.37 Ant agriculture is a fascinating subject and something that I’ve been very interested in for a long time. So, um, many ants, uh, behave in such a way that is very similar to, um, to, to human agriculture. So they cultivate some kind of crop.

Corrie Moreau: 0.0.59 – 0.1.13 .So I think humans are thought to be about, uh, a quarter of a million years old, like two hundred and fifty thousand years, so they haven’t even reached the million year mark. And we’re saying ants are about a hundred and forty to a hundred and sixty-eight million years, so ants have been around for a very long time.

<this may be a better place for the graphic that Jason mentions in the intro, or Broll of ants on plants>

Corrie: 0.1.49 – 0.2.12 we see a rapid burst in the diversification of the ants, and that seems to correspond with where we see the rise of the angiosperms, or flowering plants.

< Broll of ants with aphids/humans with cows>

Corrie: 0.4.21 – 0.4.52 We also begin to see ants having associations with homopterous insects, so you may have noticed in your, in your local gardens, that you may have problems with aphids, where they’ve all gone out and they’re feeding on your rose bushes. And you often see that you’ll have ants that tend to those aphids. And essentially protect them. So ants began to have associations with these homopterous insects that are providing honeydew and feeding on the sap of the f-, plants, and also, these ants were essentially herding and taking care of these aphids, that again allowed them to diversify.

< Plenty of Leafcutter Broll from BU and Ecuador, plus shots from Lorriane or Jaime of humans processing agricultural plants – use with wild abandon during next sections>

<Use a quote from Kari about leafcutters as well if possible>

Megan: 0.23.30 – 0.24.29: Ant agriculture is known from a lot of different systems, for instance, leafcutter ants in, uh, the r-, in tropical rainforests, in places like Peru and Costa Rica, and, and, um, and most of Central and

South America are actually, um, leafcutter ants are, are famous of course, for, for being, uh, one of the most important herbivores in, in South America. They, um, eat huge, huge, e-, well, they don’t eat, they collect huge and huge amounts of leaves, and bring them back to the nest.

Clip name: Mario - leafcutters

Mario: 0.9.50 – 0.10.18

.So everyone sees leafcutters out, uh, outside the nest, cutting leaves and carrying them back to the nest. Well, when they get there, they’re using those leaves to build a fungal colony. They’re, they’re building essentially a garden that they’re going to grow fungus on and then eat.

Stefan: 0.35.57 – 0.36.39 Essentially they cultivate fungi much the same way that we do. Um, they, they are not, um, you know, most human agriculture is getting seeds and planting seeds and tending the plants and then harvesting the plants, um, you know, we-, ants cultivate fungi much the way we do, which is, they prepare sort of a compost and they inoculate the compost and then get the fungi an-and then, uh, the fungi grow, an-and, by controlling the environment, um, so it’s cert-, it’s definitely an agricultural process.

Clip name: mclurkin_different sized ants and robots

Timecode: 0.23.42.3 to 0.25.25.10

James: In leafcutter ants, there are very large major workers that, that can be, um, about this big <uses fingers to illustrate sizes, sizes get smaller as he progresses> , very large ants, um, they cut through twigs, they do heavy lifting. Um, there are smaller workers who cut the leaves and do most of the work in carrying the leaves around.

Um, smaller worker that then tend to the, to the fungus and chew it up and plant the stuff, and even smaller workers yet who go through the very small cracks of the fungus gardens, um, to try to, to weed the fungus and keep it healthy. The, so, they have, um, uh, different sizes of workers to do different tasks. Different body types and different tasks.

Corrie Moreau: 0.23.11 – 0.24.16 So it’s a unique situation in which you have ants that go out and cut down pieces of foliage to grow fungus on, and that’s because these ant species live and feed exclusively on the fungus. So even when you c-, see them carrying back these pieces of leaves, they don’t feed on the leaves.

They’ll take the leaves back and cut them into small bits, to grow fungus. And that’s actually what they’re living on.

Megan Frederickson: 0.43.30 – 0.44.1 By some estimates a colony of leafcutter ants can actually collect more vegetation so consume more leaves in a day than a cow, it’s something like more than 50 kilos or 100 and some odd pounds of leaves can be collected by a colony of leafcutter ants in a day which is a really astonishing amount.

< Time lapse of leafcutters eating flower would go well here, maybe then to a close up on leafcutter ant head as

Corrie starts>

Corrie: 0.7.37 – 0.7.51: it’s really amazing to see ants under a microscope. They’re so incredibly diverse and so beautiful.

<Kari also said something about ants being beautiful, could use that here with some of her images>

Corrie: 0.18.10 – 0.18.44 So, people’s…interactions with ants are often not positive, and that’s because usually, unless people are out looking for ants in their natural environment, the only time they encounter them is when they come in their house, or at their picnic. Now, I grew up in the South, I grew up in New Orleans, and so we have a giant problem with the n-, um, imported red fire ants. And they’ve actually gotten so severely terrible that you really can’t go outside and have a picnic in your yard anymore. And so in that situation, I understand why people really feel negatively towards ants. The only ants that they actually encounter are making their lives difficult.

Clip name: mclurkin_insects perceived in movies

Timecode: 0.34.52.4 to 0.35.6.3

Content:

Insects are creepy, crawly kind of things, and in movies, they’re, they’re perceived as bad, and there’s always a whole bunch of them that try and eat people, and they’re big and they sting,

<Could add the bit Shaun started with Stefan/THEM! here>

Stefan 0.14.47 – 0.15.3: you know, I’m not defensive about, about, uh, studying ants, or feeling like I have to, I have to have, like, some cosmic statement of great meaning about why ants are, uh, you know, it’s worthwhile to study ants, given the idiotic things that most of us do, you know, for, for our living.

<future applications section begins>

James McLurkin: My name is James McLurkin. I’m a graduate student at the MIT Computer Science and

Artificial Intelligence Lab. The goal for my research is to understand how to write software for large numbers of robots… (w/i 0.1.28.0 to 0.1.42.9)

<B-roll of the two robots on the carpet>

James McLurkin audio: Ants…

<B-roll of the two robots on the carpet>

James McLurkin: …have solved many of the very hard problems that I’m trying to solve in my research.

They’re able to communicate, they’re able to cooperate and coordinate their, uh, behaviors… (w/i 0.1.46.0 to

0.2.28.23)

<B-roll of leafcutters: footage where ants help each other cut and carry pieces of leaves>

James McLurkin: …the kinds of things that you’d want, um, robots to do that would be useful, if you wanted to search a building to find, uh, survivors of an earthquake, or to go through a cave looking for chemicals, or to go through a forest fire looking for hotspots, or to search Mars for fossils. Um, those kinds of, of searching behaviors, um, are one of the key applications for multi-robot systems. (w/i 0.15.14.22 to 0.15.50.25)

<B-roll: split-screen of two ants following each other, two of McLurkin’s swarm robots following each other>

Mario Muscedere: …you have an ant, it’s like a little working robot. Um, what’s the best way to arrange these robots so they get the most work done? (w/i 0.5.57.0 to 0.7.28.0)

Mario:Um, but what I’m really interested in looking at is how do they, in essence, how do they make decisions about what they should be doing, and what factors within the brain are influencing the behaviors that these ants are doing?

<Add a little more detail about Mario’s brain work along with some of his images >

Clip name: mario- brain determining behavior

Timecode: 0.8.55.0 to 0.9.18.0

Mario: Ants are animals, their brains are different than ours. But, in essence, their brain is controlling their behavior, in some way analogously to how our brain is doing that. And so I think it’s always good to sort of understand how normal processes affect behavior.

<could also mention Kari’s work with ants as bioindicators here?>

<Now we shift from ants as inspiration for robots to ants and their place in the ecosystem, perhaps signal this change in subject with a fade-out to black and then a fade-in to:>

Stefan Cover: “ Go to the ant, thou sluggard. Consider her ways and be wise.” (w/i 0.8.51.0 to 0.9.15.0)

<B-roll: sped-up footage of ants harvesting a leaf: illustrates their hard-working nature>

Stefan Cover audio: …ants actually are a very important part of those natural ecosystems… (w/i 0.15.43.0 to

0.16.5.0)

<B-roll: ants eating a dead grasshopper from Amy Mertl’s Ecuador B-roll (we have 30 seconds worth)>

Stefan Cover: …that function to, you know, provide us with, uh, y-you know, the, the air we breathe, and the water we drink, and the food that we eat. (w/i 0.15.3.0 to 0.15.44.0)

<B-roll: sped up footage of clouds going by, rivers flowing, people harvesting food. We could really use agricultural footage here.>

Kari Ryder-Wilkie: …they’re so important to the rest of the…environment, the ecology of the area. They have so many diverse, um, interactions with other…living organisms… (0.26.17.0 to 0.26.32.6)

<B-roll: unknown. Does anyone have footage of ants with aphids?>

Corrie Moreau: … human societies can benefit from our knowledge of ants, and, and I mean that we benefit from knowledge of the natural world overall. (w/i 0.13.13.0 to 0.13.44.0)

<B-roll: show James Traniello, Stefan Cover, and Mario Muscedere collecting ants, try to fade out on an interesting shot, coinciding with the end of Corrie’s audio.>

Corrie Moreau audio: …having a better understanding of that evolutionary history and that knowledge is beneficial to humans. (w/i 0.13.13.0 to 0.13.44.0)

< Just an idea - When I was filming the end collecting B –Roll, I had an image of using one of the shots for the ending , a slow zoom out from the three ant collectors to see the highway behind them bustling with cars (its at

0:36:44 – 0:39:23 in my B-roll transcript, although the timecodes will be different on the new copy of that tape). I though this would go well with Stefan’s quote at 0.41.26 – 0.43.7:

“ Human beings make, they, the, um, it’s a laughable assumption, but th-, it’s not really very laughable, considering how trapped we are in it. Which is to say that ours are the only meaningful lives on the planet, you know. That somehow there’s a difference between humanity and, you know, the rest of, you know, other animals and plants and the universe and this and that. We’re living the only, um, meaningful lives, and that, you know, all this other stuff is important only as it impinges on us. Well, ants are a perfect example of, I think, of, of, you know, that other, other beings’ lives are just as important and as vivid and as, uh, meaningful, whatever that means, … And you can see it if you watch them, you watch them running around, doing all this stuff, um, you know, they’re, they’re, they’re, you know, ex-exhibiting all these complicated behaviors, it, um, it, it, it-it’s just obvious that this is just as worthwhile and just as meaningful and just as valuable, um, as, as, as what we do, you know, and, and I think y-, I mean, for me, I’ve learned to respect that. That, I have great, great respect for that.”>