Goals and Objs.doc

advertisement

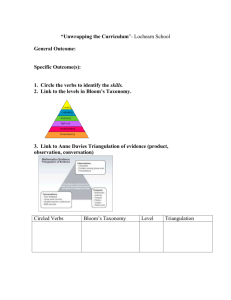

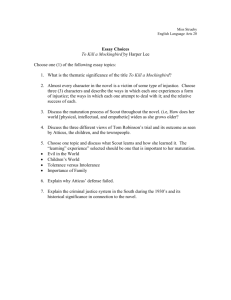

EDU 461/761 Writing Goals and Objectives Writing proper goals and objectives is one of the most important things you can do to structure the learning and activities you plan for your students. You must know where they are going or have an end in mind (a goal), along with a strategic plan (proper objectives) for how they will get there. In other words, you must have a meaningful answer for their question of why do I have to do this? The first and foremost thing you must do is make the distinction between a goal and an objective. Very simply, goals are the end products you want your students to produce; goals are what your students will do with the learning. Objectives are a scaffold of steps that your students will take toward that end goal. Both goals and objectives must be strategically planned and connected to each other to ensure a rich and meaningful learning experience for all students. Begin with the End in Mind: Write SMART Unit Goals What is a SMART goal? SMART is an acronym that can be used to help ensure that effective and achievable goals are set for your students. Although there are some variations with letters A, R, and T, generally a SMART goal is: Specific Measurable Attainable Results-focused Timely A qualifying description of each component of the acronym is found below. Specific Specific goals are clear and well defined. This helps both the performer (student) and the manager (teacher/facilitator) because the performer knows what is expected of him and the manager is able to monitor and assess actual student performance against the specific goals. Measurable Progress towards goals often needs to be monitored while work is under way. It is also very useful to know when that work has been done and the goals are completed. A measurable goal achieves this end. Attainable When trying to reach a goal, the learner may not be able to achieve it for various reasons including a lack of skill, not having access to enough resources, and not having management support. Writing attainable goals ensures that everything is in place and that if the student does not reach the goals, he cannot reasonably point fingers elsewhere. Writing attainable goals leaves no room for student excuses. Results-focused This is where beginning with the end in mind is most important. Writing results-focused goals helps to define the purpose of the lesson, activity, or unit. Results-focused goals ensure that learning is meaningful, relevant, and purposeful. Timely SMART goals also have an element of time embedded within. This means a specific timescale of what is required by when is clearly included. Providing a timescale adds an appropriate sense of urgency, helping students stay focused on the task and the end result. EXAMPLES OF SMART GOALS: After reading To Kill a Mockingbird students will be given three class periods to choose one critical lens, plan and write a proper Regents task essay with developed ideas, textual support, and a discussion of key literary elements and devices earning no less than a 4 on the state rubric. Given a four-week unit on the novel To Kill a Mockingbird and four class periods in the computer lab, students will create an electronic publication based on events and characters in the novel that includes a proper masthead, five news articles with engaging headlines, two pictures with proper captions, a 200 word editorial, an appropriate advertisement, and an obituary. After reading the novel To Kill a Mockingbird and given direct instruction in writing a Regents Task 3, students will choose an appropriate song or poem that has a connection to an important character or theme in the novel and write a well-developed formal essay with an established controlling idea, a detailed explanation of how the poem or song relates to the novel, and specific textual details earning no less than a 4 on the state rubric. Stepping Toward Unit Goals Writing Strategic Objectives EDU 461/761 Remember, objectives are stepping stones your students will use to reach the end goal. Writing strategic objectives is the result of understanding that learning is a process that your students must experience or live through. It is up to you to provide them with appropriately structured and properly sequenced building blocks or steps that lead to them doing something meaningful and assessable with the learning. In order to provide your students with a proper scaffold of learning, use Bloom’s Taxonomy as a guide. Benjamin Bloom developed his taxonomy of learning after years of studying human development and how the brain learns. There are six levels of understanding, each clearly building on each other. Lower Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy are considered surface learning and are the basis of most lessons early on in a planned unit or learning experience. Knowledge – the facts Comprehension – proof of understanding Application – using the knowledge or facts Upper Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy are considered higher order thinking skills that provide for a much deeper level of understanding. These levels are used as some of the final steps of achieving the goals of the unit or planned learning experience. Analysis – looking at the parts of the knowledge Synthesis – doing something new with the learning Evaluation – judging the data learned Four Elements of Strategic Objectives Writing objectives for the lessons leading up to the unit goal is as simple as A, B, C, D. Be sure your objectives include each of the four elements described below: 1. Audience = the students (TSWBAT “The students will be able to…) 2. Behavior = a verb from the proper level of Bloom’s Taxonomy 3. Condition = pre-requisite tasks the student must complete or supplies the student needs to accomplish the specified task 4. Degree = a minimum number of items completed to prove the students have learned what you had planned or intended Sample Objectives: Read each objective and identify the audience, behavior, condition, and degree within. 1. After reading and discussing Washington Irving’s “The Devil and Tom Walker,” James Fennimore Cooper’s excerpt from The Prairie, William Cullen Bryant’s “Thanatopsis,” and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the students will be able to list four characteristics of American Literature during the Romantic Period. 2. After reading and viewing To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, the students will be able to differentiate between a character’s internal and external conflicts and support each type with specific and relevant details from the text. 3. After listening to and reading Jonathan Edwards’ Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God and identifying several examples of figurative language, the students will be able to illustrate and label two images found within. 4. After reading and discussing the chapters concerning an episode in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the students will be able to design an audiovisual project, which will illuminate the episode for those who have not read it. 5. After reading Ernest Hemmingway’s “Big Two-Hearted River” and listening to several parodies of it, the students will be able to rewrite another short story of the curriculum in parody form or compose an original version of a parody for “Big Two-Hearted River” as a submission to a Hemmingway parody contest. 6. After listening to explanations of participial, gerund, and infinitive phrases, in addition to completing worksheets on these phrases, the students should be able to integrate these phrases into their own writing, with an 85% rate of correctness in regard to placement and punctuation.