Modeling Strategic Decisions and "Scenario Analysis"

advertisement

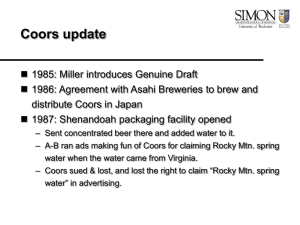

BA389 - Strategic Management - Johnson Modeling Strategic Decisions and "Scenario Analysis": Coors Brewing and Capacity Expansion To support strategic decision-making, it is often useful to build a quantitative model of the decision a company faces. Building such a model is useful for a number of reasons. For example, the modeling of a decision forces us to carefully think about the business we are in. What are the economics of the industry? How do we generate revenues? What does our cost structure look like, and how does it change as we change the scale and scope of operations? In addition, we are forced to explicitly define the assumptions underlying the model; in particular, the variables we can't control. Going through such analysis is extremely valuable because it can improve the quality of the decisions we make. However, building the model is just the beginning. To fully understand the risks and subtleties of a decision, one must "play" around with the model, changing one's assumptions and running through the scenarios that might occur. For your first group project, you will build a model of the decisions facing Airbus and Boeing in the commercial aircraft industry. To help prepare you for this analysis, I am providing you with a spreadsheet I put together analyzing a capacity decision by Coors Brewing in the mid1980s. To analyze this situation, I put together a pro forma cashflow statement for Coors and attempted to measure the NPV for different scenarios or options that Coors had. In your analysis of Airbus vs. Boeing, you will be expected to put together a similar model for Airbus and Boeing (however, it will not be exactly the same because the economics of the commercial aircraft industry differ significantly from the brewing industry), and run through various scenarios and options available to these companies. In the Coors spreadsheet, Coors is entertaining the possibility of becoming a national brewer, similar to Anheuser-Busch and Miller. To implement this strategy, Coors needs to build additional capacity supporting national distribution and expand its advertising campaigns promoting a national brand image. In particular, Coors is looking at building additional capacity in Virginia to support east coast distribution of their product. The spreadsheet supports the analysis of both Coors current position as well as the strategic options the company has available. Two final points: 1. In your spreadsheet for Airbus and Boeing, I don't expect you to put the "buttons" in for the various scenarios. If you want to, that's great! In addition, it makes it a lot easier to "flip" between scenarios. If you would like to learn how to put "buttons" into a spreadsheet stop by my office, and I will show you how. 2. The Airbus vs. Boeing assignment is more complicated than this Coors example in that for Airbus vs. Boeing, you are expected to take into account the potential game theoretic interaction between Airbus and Boeing. As we get closer to the assignment, it will become more clear what this means. The Brewing Industry In the mid-1980s, companies in the brewing industry could be divided into several different strategic groups. First, there were the large national producers, such as Anheuser-Busch and Miller Brewing, which marketed their brands on a national basis and had breweries located across the United States. Second, there were regional breweries, such as Rolling Rock, Genesee, or Lone Star, which concentrated on specific geographic markets and did not have extensive national distribution. Prior to the 1950s, the structure of the U.S. brewing industry was completely characterized by regional production with each area of the country being serviced by a few breweries usually located in large urban areas. The reason for the existence of this industry structure was that beer is extremely costly to transport (as is true for other non-concentrate beverages). In addition, there were issues associated with maintaining the "freshness" of the product. Thus, there was a tendency for brewers to maintain a regional focus. However, the advent of television changed the nature of the industry. Television created huge economies of scale in advertising; the cost of promotional campaign was basically the same independent of whether it had a regional or a national focus. Thus, the average cost of delivering advertising to consumers fell with the geographic scale of the campaign. One of the first brewers to recognize the potential benefits of economies of scale in advertising was Anheuser-Busch (AB). Developing a first-mover advantage, AB quickly built breweries across the United States in the 1950s and 60s and attempted to increase the economies of scale in brewing as well; at the same time, AB also made extensive investments in advertising on a national scale. This created a situation where AB was one of the only brewers with national coverage in brewing as well as an advertising campaign to back up this extensive distribution system. As a result of such efforts, AB had become a brewer with over 74 million barrels of capacity by the mid-1980s. In addition to Anheuser-Busch, Miller Brewing also made similar investments in order to make itself into a "national" brewer. Besides the national and regional brewers, one can also identify a third strategic group in the brewing industry, the "super-regionals." Among the firms using such a strategy would be Heileman, Stroh's, and Coors Brewing. Coors was the prototypical super-regional brewer. Coors Brewing All of Coors brewing capacity, some 16 million barrels in 1985, was located in Golden, Colorado, and its market focus was the western United States. In the geographic centralization of Coors had been caused by two factors. First, during the 60s and 70s, there was significant demand growth in the Rocky Mountain region which caused Coors to expand production in Colorado. Second, Coors was more vertically integrated than other brewers, having built packaging facilities near its breweries in Golden. Once those facilities were in place, it decreased Coors incentives to expand production to other parts of the country. Historically, Coors used little TV advertising and depended on point-of-sale promotions and word-of-mouth to promote its beer. Over time, Coors had developed a special and distinctive image among beer-drinkers. With its "Rocky Mountain Spring Water" and other choice ingredients, Coors had developed a cult-following among beer drinkers; individuals would often transport cases of Coors to friends in other parts of the country where Coors was not available. A Change in Strategy Beginning in the late 1970s, Coors began to exploit the brand value it had developed by slowly expanding its national presence. Coors gradually expanded its capacity in Colorado and increased national advertising (It should be noted that minimum efficient scale of an advertising campaign was around $150 Million). By the mid-1980s, Coors had reached crossroads. Would they continue with their "super-regional" strategy? Or, would they attempt to change strategic groups and become a "national" producer similar to Anheuser-Busch? This issue was a difficult one to address because executing a strategy similar to AB would involve significant sunk, capital investment. For example, by the early 80s, the minimum efficient scale plant had brewing capacity in the neighborhood of 4-5 million barrels and cost in the range of $250-$300 million to build. On the other hand, it did not look like Coors could stand still either. By continually expanding economies of scale (through technological innovation) and efficiencies in advertising, AB and Miller were decreasing the average cost of producing and marketing a barrel of beer. If Coors did not find some way of competing with this increasingly important threat, Coors might find itself squeezed out the market. In looking at this situation, Coors had several options before it: 1. Build a brewing and packaging facility in Virginia. This option would involve capital investment of approximately $450 million dollars to build a 10 million barrel plant and locate a facility supporting East Coast distribution of Coors. One difficulty with the option was that AB and Miller already had significant market share on the East Coast and market growth was slowing down. In part, the larger than MES capacity was driven by the economies of scale in advertising (Why?). 2. Expand production in Golden and build a bottling plant in Virginia. This option was less risky than option one in that it utilized existing excess capacity in Colorado. However, it significantly increased distribution costs because it involved putting the beer into refrigerated railcars, which would then take the beer to Virginia for packaging. 3. Build a 5 million-barrel MES plant in Virginia. Finally, another option was to build a smaller brewing and bottling plant in Virginia. This would reduce the risk associated with the investment in physical capital, but what would it imply about the economies of scale in advertising? Now, take a look at the spreadsheet for Coors (You can download the spreadsheet from my webpage). The spreadsheet contains several individual worksheets, detailing the economies of scale in brewing and advertising as well as a cashflow analysis of the decision. On the cashflow sheet, notice that there are four buttons on the spreadsheet. By clicking through the buttons, you can change the scenarios and see how the NPV changes. What explains the differences? In part, the differences are driven by changes in the revenue, cost, capital expenditures associated with each option. In particular, as economies of scale in advertising and brewing change depending on which option you choose. Also, the variable costs of transportation change depending on where the plant is located. Try to understand what is causing the differences across the options.