Reaction Paper

advertisement

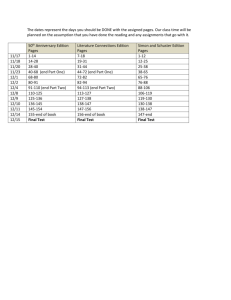

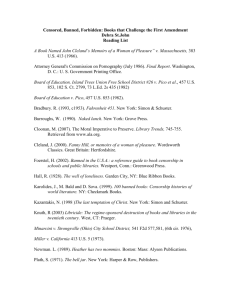

Kearston Wesner MMC 5206 Discussion/Reaction Paper #1 October 10, 2007 The issue in this discussion paper is whether Florida’s Civil Restitution Lien and Crime Victims’ Remedy Act of 1994,1 which prevents convicted felons and people acting on their behalf from profiting from any account of their crimes, is constitutional. A. First Amendment Issue The First Amendment issue in this case is whether the Florida Law unconstitutionally suppresses an individual’s speech because it requires her to disgorge her profits from works she co-wrote with, or on behalf of, a convicted felon. B. Simon & Schuster In 1977, David Berkowitz (the “Son of Sam” serial killer) terrorized New York, and was later apprehended. Later, he had the opportunity to profit from telling his story. Recognizing it was unfair for Berkowitz to profit at the expense of his victims, the New York legislature passed the New York “Son of Sam” Law.2 The New York Law was intended to prevent an accused or convicted criminal, or anyone who contracted with that person or that person’s representative(s), from profiting from any of the person’s works on any subject related to the crime.3 The money, instead, would be earmarked for the victims and the victims’ families.4 1 FLA. STAT. § 944.512 (2007) (“Florida Law”). N.Y. Exec. Law § 632-a (McKinney 1982 and Supp. 1991) (“New York Law”). 3 Id. 4 Id. The law set forth a prioritized scheme for how the funds would be distributed. First, the Board would release assets for legal representation, and then to cover any expenses associated with maintaining the escrow account. Id. at § 632-a(8). Then, in order, the money would cover “subrogation claims of the State for payments made to victims of the crime,” civil judgments, and creditors’ claims. Id. at § 632-a(11). 2 In Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. N.Y. Crime Victims Board,5 the United States Supreme Court determined that the New York Law was unconstitutional.6 In Simon & Schuster, the Court considered a contract between Simon & Schuster and “organized crime figure” Henry Hill.7 Hill contracted with an author, Nicholas Pileggi, to write a book, Wiseguy: Life in a Mafia Family, which described Hill’s life in organized crime, and detailed the crimes he had committed. Simon & Schuster published the book. The New York Crime Victims Board demanded that Simon & Schuster turn over its profits under the New York Law because it had contracted with Hill, a criminal. Simon & Schuster sued under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, seeking a declaration that the New York Law violated the First Amendment, and requesting an injunction. The District Court said the statute was constitutional, and the Court of Appeals affirmed. The Supreme Court reversed. It explained that the New York Law imposed a “financial disincentive on speech of a particular context,” here a criminal’s recollection of his crimes.8 Because the statute discriminated against certain speech, the government had to show that it served a “compelling governmental interest” and was narrowly-tailored.9 The Court said that while the State has a “compelling interest in compensating victims from the fruits of the crime,”10 which include book royalties,11 the New York Law was unconstitutionally overbroad.12 First, the statute applied to all works 5 Simon & Schuster, Inc. v. N.Y. Crime Victims Board, 502 U.S. 105 (1991). Id. at 123. 7 Id. at 111. 8 Id. at 116, 117. 9 Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc. v. Ragland, 481 U.S. 221, 231 (1987), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 118. 10 Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 120; Caplin & Drysdale, Chartered v. United States, 491 U.S. 617, 629 (1989)(in the Sixth Amendment context, recognizing the government’s interest in compensating victims), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 119. 11 Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 119. 12 Id. at 121; see Children of Bedford, Inc. v. Petromelis, 77 N.Y.2d 713, 727 (N.Y. 1991)(stating “no one shall be permitted to profit by his own fraud, or to take advantage of his own wrong, or to found any claim upon his own iniquity, or to acquire property by his own crime”), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 119. 6 that merely touched on the crime, “however tangentially or incidentally.”13 Second, it brought under its ambit anyone who admitted to a crime, regardless of whether he was accused or convicted.14 Hill, for example, was never convicted of a crime. He was given immunity from prosecution in exchange for testifying against his colleagues. Furthermore, even someone who wrote a book including a paragraph on how he shoplifted as a kid would technically have been required to turn over his profits under the New York Law.15 Clearly, this statute was not narrowly tailored to advance the government’s interests.16 The Court was not persuaded by the Board’s argument that financial discrimination only violated the First Amendment when it suppressed “certain ideas.”17 Even a statute “aimed at proper governmental concerns” can violate the First Amendment.18 Thus, even though the New York Law addressed a legitimate governmental concern, and did not silence a particular opinion but speech of an entire segment of the population (accused or convicted criminals), it was unconstitutional. C. The London Case Sondra London co-wrote two books with convicted serial killer Danny Rolling, detailing Rolling’s crimes. She also covered the case for The National Enquirer and “A Current Affair,” and wrote articles for The Globe about the crimes.19 Rolling had contracted with London, giving her the rights to all of the proceeds. In all, London earned approximately $21,000.20 Florida prosecutors claimed London should disgorge her profits under the Florida Law, because London was romantically involved with Rolling and 13 Id. The Court listed a number of works that could have been prevented under the New York Son of Sam Law, including such things as Malcolm X’s autobiography (which discussed crimes he committed before he became a public figure) and Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience (because Thoreau was jailed for failing to pay taxes). Id. at 121-22. 14 Id. at 121. 15 Id. at 123. 16 Without further explanation, Justice Blackmun determined in his concurring opinion that the New York Law was both overinclusive and underinclusive. 17 Id. at 117. 18 See Minneapolis Star & Tribune Co. v. Minnesota Comm’r of Revenue, 460 U.S. 575, 592 (1983), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 117. 19 See Florida v. Rolling and London: The Serial Killer Profits Hearing, http://www.courttv.com/archive/rolling/032098.html (last visited Sept. 25, 2007). 20 Id. was, therefore, acting on Rolling’s behalf.21 On December 31, 1997, a Florida judge ruled against London. London indicated she would appeal. At first blush, the Rolling case is factually similar to Simon & Schuster. There are a few differences, however. First, the Florida Law is being invoked against an author, while the New York Law was invoked against a publisher. Second, London is accused of acting on Rolling’s behalf because she was romantically involved with Rolling, and therefore not a disinterested journalist. There’s an underlying question of whether having a romantic relationship with the convicted felon is enough to claim the individual is actually acting on the felon’s behalf. D. Analysis I believe that if the Supreme Court were to grant certiorari in the London case, it would find that § 944.512 does not pass constitutional muster. Political or social speech is given the utmost protection under the First Amendment. London’s books and articles are social speech, and therefore, any restraints on that speech are presumptively unconstitutional. The Florida Law subtly suppresses speech. It does not specifically prevent someone from speaking, but the financial burden it imposes effectively restrains speech. Like the New York Law, the Florida Law is a content-based restriction on speech because it isolates income from speech “for a burden the State places on no other income,” and is directed at particular speech.22 Statutes are “presumptively inconsistent with the First Amendment if [they] impose[] a financial burden on speakers because of the 21 Id. See Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 116; see also Arkansas Writers’ Project, Inc. v. Ragland, 481 U.S. 221, 230 (1987) (invalidating a magazine tax because “[o]fficial scrutiny of the content of publications as the basis for imposing a tax is entirely incompatible with the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press”), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 115. 22 content of their speech.”23 The State has to show that its statute addresses a “compelling governmental interest,” and is narrowly-tailored to achieve that means. In Simon & Schuster, the Supreme Court says that states have a compelling interest in compensating the victims of crimes24 and ensuring criminals do not profit from their crimes.25 However, the Court invalidated the New York Law for overbreadth.26 In so ruling, the Supreme Court opened the door to other states drafting a more narrowly-tailored version of the New York Law. The Florida Law, however, is still overbroad and vague. A statute is overbroad if “a substantial portion of the burden of speech does not serve to advance [the State’s content-neutral goals].”27 First, the Florida Law first says that a convicted felon, or someone acting on his behalf, cannot receive “royalties, commissions, proceeds of sale, or any other thing of value payable or accruing to [him].”28 Yet it does not define what a “thing of value” is, or provide any guidance for how the courts should define it. In the same vein, the statute applies to convicted felons and the people who “act on [their] behalf,”29 but does not explain what this entails. The limited guidance it gives is noting that it covers every person to whom “the proceeds may be transferred or assigned by gift or otherwise.”30 As written, this begs the question of if the convicted felon/author gives a quarter to a panhandler, is that panhandler now deemed to be acting on the felon’s behalf? Finally, this statute would apply to any convicted felon – even one convicted of a “victimless” crime, which hardly addresses the government’s asserted interest in victims receiving compensation. 23 Leathers v. Medlock, 499 U.S. 439, 447 (1991), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 115. Simon& Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 118. 25 Id. at 119. 26 Id. at 121. 27 Ward v. Rock Against Racism, 491 U.S. 781, 799 (1989), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. 122. 28 FLA. STAT. § 944.512(1). 29 Id. 30 Id. 24 Hypothetically, then, if a convicted bigamist intended to write a tell-all book and give all the proceeds to an orphanage, he could not under the Florida Law. This is even though neither asserted governmental interest – compensating victims or ensuring the criminal does not profit from his crimes – is being advanced. Another strange aspect of this statute is that it is designed to protect victims, but the first 25% of the proceeds are earmarked for the convicted felon’s dependents.31 In my opinion, this is a transparent attempt by the legislature to “show” that the restriction on speech is not as onerous as it may seem, because the convicted felon’s dependents still get a piece of the pie. Providing for the felon’s dependents does not, however, mean that the First Amendment concerns vanish. I believe this portion of the statute distracts from the core issue – unconstitutionally restraining speech. All of that said, the Florida Law is more narrowly-tailored than the New York Law in the respect that it only applies to convicted felons or people acting on their behalf, not to anybody who says he committed a crime. The Florida Law also defines what qualifies as a “conviction” for statutory application purposes.32 Yet as discussed above, it is still overbroad. Finally, even though Rolling’s book is salacious, and the idea of his ex-fiancee/co-writer profiting from the book is morally repugnant, the First Amendment is especially designed to protect the expression of “offensive or disagreeable” ideas.33 Curbing free speech, even when the speech is highly distasteful, is a dangerous idea. Whether the content of her tome is tacky is irrelevant. 31 FLA. STAT. § 944.512(2)(a). FLA. STAT. § 944.512(1). (defining a “conviction” as “a guilty verdict by a jury or judge, or a guilty or nolo contendere plea by the defendant, regardless of adjudication of guilt”). 33 See United States v. Eichman, 496 U.S. 310, 319 (1990) (saying “[i]f there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the Government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive of disagreeable”), cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 118; see also Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46, 55 (1988)(stating that: “The fact that society may find speech offensive is not a sufficient reason for suppressing it. Indeed, if it is the speaker’s opinion that gives offense, that consequence is a 32 E. Conclusion The Florida Law is likely unconstitutionally overbroad. It encompasses more speech than the government has a legitimate interest in curbing. reason for according it constitutional protection.”), quoting FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, 438 U.S. 726, 745 (1978), and cited by Simon & Schuster, Inc., 502 U.S. at 118.