teachers` notes

advertisement

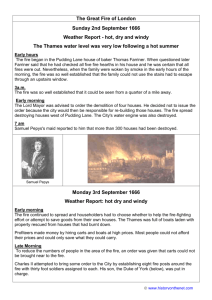

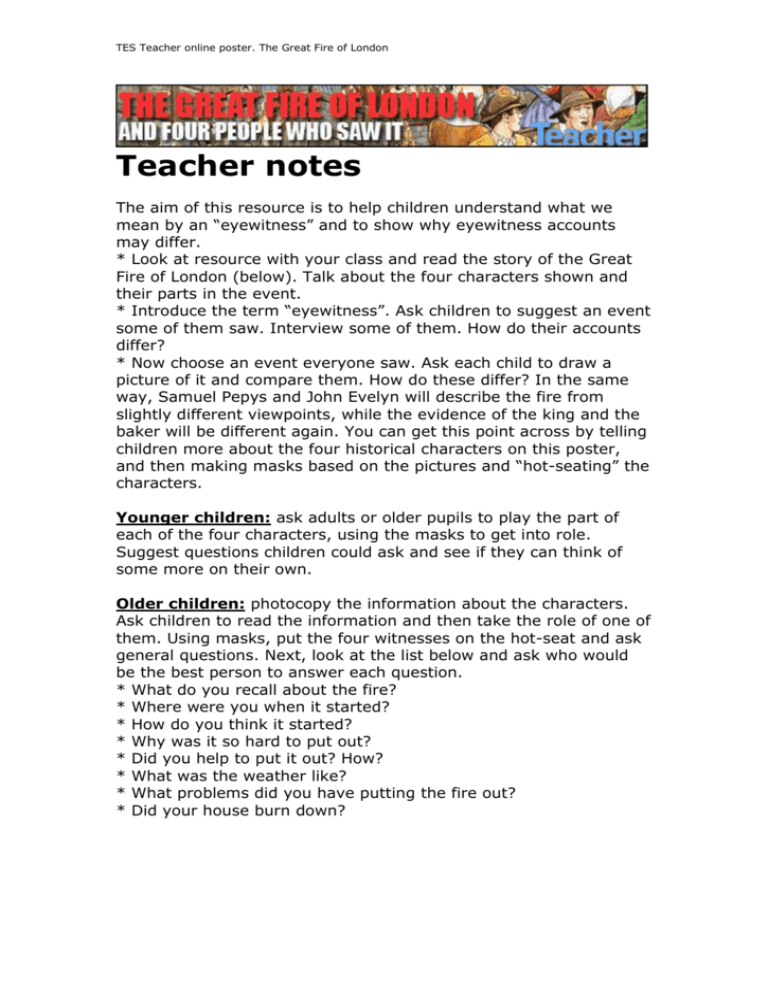

TES Teacher online poster. The Great Fire of London Teacher notes The aim of this resource is to help children understand what we mean by an “eyewitness” and to show why eyewitness accounts may differ. * Look at resource with your class and read the story of the Great Fire of London (below). Talk about the four characters shown and their parts in the event. * Introduce the term “eyewitness”. Ask children to suggest an event some of them saw. Interview some of them. How do their accounts differ? * Now choose an event everyone saw. Ask each child to draw a picture of it and compare them. How do these differ? In the same way, Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn will describe the fire from slightly different viewpoints, while the evidence of the king and the baker will be different again. You can get this point across by telling children more about the four historical characters on this poster, and then making masks based on the pictures and “hot-seating” the characters. Younger children: ask adults or older pupils to play the part of each of the four characters, using the masks to get into role. Suggest questions children could ask and see if they can think of some more on their own. Older children: photocopy the information about the characters. Ask children to read the information and then take the role of one of them. Using masks, put the four witnesses on the hot-seat and ask general questions. Next, look at the list below and ask who would be the best person to answer each question. * What do you recall about the fire? * Where were you when it started? * How do you think it started? * Why was it so hard to put out? * Did you help to put it out? How? * What was the weather like? * What problems did you have putting the fire out? * Did your house burn down? TES Teacher online poster. The Great Fire of London Text to share with pupils The fire broke out at the end of a hot summer when everything had been dried out by the heat. Most houses were made of wood, and in London they were built very close together. The fire began in a baker’s shop in Pudding Lane on September 2, 1666. The baker was Thomas Farryner. When asked later how the fire started, he said he had checked that everything was all right before he went to bed but his family was woken in the night by the smoke and they had to climb out of a window and escape on to a neighbour’s roof. One maidservant was afraid to jump and they left her behind. By the middle of the night, the fire was so big that it could be seen far away. Somebody woke up the Lord Mayor, but he didn’t think the fire was serious and went back to sleep. Next morning, Samuel Pepys’s maid told him that 300 houses had burnt down. He went to see for himself and found the fire roaring away and nothing was being done to stop it. He told the King of the danger and the King gave him a message for the Lord Mayor of London. The King said the Lord Mayor must pull down enough houses to make gaps. Then the fire would have nothing to feed it and it might burn out. Pepys found the Lord Mayor. When he heard the King’s message, the Lord Mayor cried out: “Lord, what can I do? I am worn out! People will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses, but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.” On the same day, John Evelyn went to see the fire. He said it was windy, and the wind fanned the flames so they leapt from house to house and street to street. He said the long hot summer had heated up the air and made everything as dry as firewood. The King and his brother James, the Duke of York, took charge of the fire-fighting. They ordered their men to blow up houses to make gaps while others pulled down the burning roofs with hooks and poured water on the flames. But the wind continued to blow, and the great fire raged on. Samuel Pepys was afraid his own house would catch fire, so he took his money and valuables and rode to a friend’s house, where he left them for safe-keeping. Then he returned home and dug a pit in the garden. He buried his wine and some special cheese in it, hoping to save them from the fire. TES Teacher online poster. The Great Fire of London That same day, the King put John Evelyn in charge of a fire-fighting team. He said the fire was so hot it melted the metal of the roofs of churches and the pavements were glowing red-hot. By now the firefighters were very tired. Much of their equipment was broken and they were running out of water. The next day, the wind dropped. This stopped the fire from spreading and the flames began to die down. By the end of the week it was out. When John Evelyn went back to see what had happened he found himself clambering over heaps of smoking rubbish. Great buildings lay in ruins and there was a smell of smoke everywhere. Thousands of people were by the roadside with things saved from the fire. People who saw the fire John Evelyn (1620-1706) John Evelyn was a friend of Pepys and, like him, he kept a diary. He was an author, garden designer and a friend of Charles II. He was in London throughout the fire and was in charge of a fire-fighting team at Fetter Lane in Holborn. Charles II (1630-1685) He became king in 1680. His favourite palace was in Whitehall, and he was there when the fire broke out. At first he did nothing because he expected the Lord Mayor of London to deal with the problem. But once Pepys warned him that the Lord Mayor couldn’t cope, the king gave orders to pull down houses and make fire breaks. His brother, James, the Duke of York, organised sailors, soldiers and policemen into teams of firefighters. The king put people in charge of these teams, and he and his brother worked bravely alongside the other Londoners. Although the fire came close to the palace of Whitehall, the building survived. When the fire was over, Charles II played a big role in the rebuilding of the city. Thomas Farryner (dates unknown) He was a baker, and his name is sometimes spelt Farriner or Farrynor. We don’t know when he was born or when he died, but he baked ships’ biscuits for the sailors in the king’s navy at his house in Pudding Lane, where the fire started. Because of the ovens, a baker’s shop was very likely to catch fire, but Farryner said that he did check the fires before he went to bed and they were all out except one and he had made sure that one was safe. TES Teacher online poster. The Great Fire of London Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) He started life as a poor East London tailor’s son but he became an important man who helped to look after the king's ships. We know a lot about him because he kept a diary describing his life. In 1666 when the great fire broke out, he was living with his wife in Seething Lane, near the Tower of London. His diary gives a vivid account of the disaster. This is how he describes the scene on the first day of the fire: “All over the Thames with your face in the wind you were almost burned by the shower of fire drops. We went to a little alehouse and saw the fire grow. As it grew darker, it seemed more and more, in corners and on steeples, between churches and houses, as far as we could see, in a most horrid, spiteful, blood-red flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire. We stayed till we saw the fire as one whole arch of flame, from one side of the bridge to the other. Churches, houses and all were on fire, all flaming at once, with a horrid noise the flames made and the cracking of the houses in their ruin.” His house burned down in another, smaller fire some years later. Boats on the Thames Extract from the Diary of Samuel Pepys September 2, 1666. So down, with my heart full of trouble, to the Lieutenant of the Tower, who tells me that it began this morning in the King’s bakers house in Pudding Lane, and that it hath burned St. Magnus's Church and most part of Fish Street already. So I rode down to the waterside, . . . and there saw a lamentable fire. . . . Everybody endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging into the river or bringing them into lighters that lay off; poor people staying in their houses as long as till the very fire touched them, and then running into boats, or clambering from one pair of stairs by the waterside to another. And among other things, the poor pigeons, I perceive, were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconies, till they some of them burned their wings and fell down. Having stayed, and in an hour's time seen the fire rage every way, and nobody to my sight endeavouring to quench it, . . . I to Whitehall (with a gentleman with me, who desired to go off from the Tower to see the fire in my boat); and there up to the King's closet in the Chapel, where people came about me, and I did give them an account [that] dismayed them all, and the word was carried into the King. So I was called for, and did tell the King and Duke of York what I saw, and that unless his Majesty did command houses to be pulled down, nothing would stop the fire.