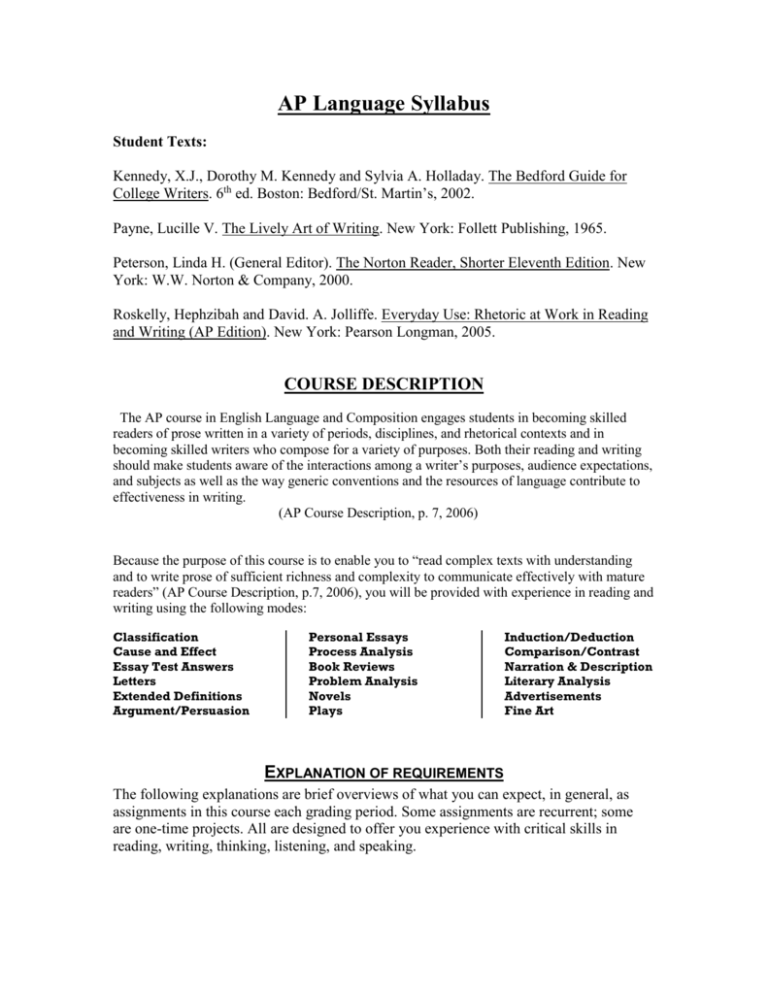

AP Language Syllabus

Student Texts:

Kennedy, X.J., Dorothy M. Kennedy and Sylvia A. Holladay. The Bedford Guide for

College Writers. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2002.

Payne, Lucille V. The Lively Art of Writing. New York: Follett Publishing, 1965.

Peterson, Linda H. (General Editor). The Norton Reader, Shorter Eleventh Edition. New

York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000.

Roskelly, Hephzibah and David. A. Jolliffe. Everyday Use: Rhetoric at Work in Reading

and Writing (AP Edition). New York: Pearson Longman, 2005.

COURSE DESCRIPTION

The AP course in English Language and Composition engages students in becoming skilled

readers of prose written in a variety of periods, disciplines, and rhetorical contexts and in

becoming skilled writers who compose for a variety of purposes. Both their reading and writing

should make students aware of the interactions among a writer’s purposes, audience expectations,

and subjects as well as the way generic conventions and the resources of language contribute to

effectiveness in writing.

(AP Course Description, p. 7, 2006)

Because the purpose of this course is to enable you to “read complex texts with understanding

and to write prose of sufficient richness and complexity to communicate effectively with mature

readers” (AP Course Description, p.7, 2006), you will be provided with experience in reading and

writing using the following modes:

Classification

Cause and Effect

Essay Test Answers

Letters

Extended Definitions

Argument/Persuasion

Personal Essays

Process Analysis

Book Reviews

Problem Analysis

Novels

Plays

Induction/Deduction

Comparison/Contrast

Narration & Description

Literary Analysis

Advertisements

Fine Art

EXPLANATION OF REQUIREMENTS

The following explanations are brief overviews of what you can expect, in general, as

assignments in this course each grading period. Some assignments are recurrent; some

are one-time projects. All are designed to offer you experience with critical skills in

reading, writing, thinking, listening, and speaking.

2

ALL GRADING PERIODS

Weekly Morpheme lists (1-21)

Bell Work Folders

Dialecticals on thematic unit readings

In Class Timed Writings

Response Journal Entries

Practice Objective Tests

Grammar Log

Mass Media and Visual Materials

Bell Work: You are expected to begin work when the bell rings. Bell Work is kept

in a three -pronged folder with NO pockets. Bell Work assignments will include but

not be limited to the following: “Show Don’t Tell” writing, Bedford grammar

exercises, quote explication, grammar practice on handouts and overheads, rhetoric

practice (Voice Lessons among other sources), AP objective practice, argument

practice handouts (identifying fallacies, inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning,

etc.), and opening sentence completions. The most challenging of BW assignments

will be the “See, Think, Wonder” assignments. You will view a piece of fine art,

describe what you see (details), write what you think the piece is about, and wonder

whatever comes to mind from viewing the piece. BW notebooks will be collected and

graded at least twice each grading period. Students should take these folders home

only if make-up work needs to be completed.

Vocabulary: Morphemes will be given in 21 groups of ten (10). You will be given

various tasks to complete for each list. With some lists you will practice sentence

writing with specific instructions; some lists require paragraph writing. All lists

require that you apply words in context. You may access all of the lists with each list’s

instructions on my web page. Assignments are due every Monday. You will take a

comprehensive test every 3 lists. The comprehensive test is modeled on the SAT and

includes sentence completions, synonyms, and antonyms. All of the words on each

test are from SAT practice books.

Response Journals: The purpose of this journal is three-fold: 1an immediate,

analytical engagement with the work; 2a long-term resource for essays and exams; 3a

personal record of your growth. The goal for keeping this journal is for practice in

seeing the relationship between structure and purpose. You will read passages

written with different purposes and subject matter; across centuries and modes.

Entries in the RJ will be teacher directed. Specific requirements for grading will be

glued to the inside front left flap of a three-pronged folder. Directions for colorcoding will be glued on the inside back flap. These journals will be kept in the

classroom and will hold all free-writes, pre-writes, essay drafts, and timed writes in

chronological order. Each nine weeks we will review your writing and you will write

a one-page summary of the improvements you see you need to make in your writing

as well as the successes you have experienced. This metacognitive exercise is how

you can measure your own learning.

Suggestions for analyzing a passage:

3

DICTION

Imagery, figures of speech, sentence structure, tense

Reasonable establishment of the degree of effect the author creates

Patterns

Shifts in patterns

BASIC QUESTIONS

What idea (claim, thesis, proposal, issue) is the author advocating?

What evidence (proof, claim) is there for that idea?

How many different arguments in favor of the idea are offered?

What is the merit of each idea?

How is the opposing point of view presented?

METALANGUAGE (talking about the passage)

What appeals (ethos, pathos, logos) are included?

What effect does this argument have on the audience?

Who is the audience?

What structural patterns (words, syntax, ideas, etc.) exist?

USE OUTSIDE KNOWLEDGE TO HELP IN YOUR INTERPRETATION

BE AWARE OF LOGICAL FALLACIES

USE DQ’S (DOCUMENTED QUOTATIONS): Make inferences based on evidence from the text

AVOID SUMMARIES!!!!

Color Marking/Coding

Read.

Read the passage one time through without marking to get a sense of it.

Read it again.

Now, reread it, this time with five colored pencils. Select one color per pattern. What do you want to

call the purple things (orange, red, etc.)?

Make a quick, simple key that labels the purpose of each color.

Reread.

Interpret.

Is one color predominate? What progression do you see through the passage? How does that progression

work? Do you need to add another color? What does the passage seem to be about?

Coding must draw inferences, relating to what you noticed the first time to patterns, techniques, ideas,

judgments. These insights go beyond the labeling stage.

Go back to your Simple Key.

Make a new one. Based on your answers, code each color according to the inference drawn.

Re-read and criticize.

What bigger ideas have been raised in the Interpretation Stage? Explore, defend, and challenge the bigger

ideas.

Dialecticals: The dialectical assignment is an important means by which you will

develop a better understanding of the texts we read in class. It is the place where

you will incorporate the ideas we discuss in class, your own ideas, and your personal

relationship with those texts. It will be invaluable to you when you prepare for

examinations, papers, informal class discussions, and Socratic seminars. Dialectic

means “the art or practice of arriving at the truth by using conversation involving

question and answer” This is what you must do in your dialecticals —dialogue with

yourself. Write down your thoughts, questions, insights, and ideas while you read.

The format will be explained in class.

Fact Find: For each novel, play, and thematic unit we will study how historical

perspective influences a work. The Fact Find requires that you bring in 7 distinct

characteristics of the era in which the piece being studied was written. We will piece

together the era using Spencer Kagan’s Jigsaw method. Each source must be cited

4

using MLA format and be from a reliable source other than an encyclopedia. The

distinction between using primary source and secondary source documents will be

discussed in class.

AP Notebook: The AP Notebook is a binder that will contain all notes on the

rhetorical and literary terms given in class. All notes on historical background should

be kept in this folder as well. This is the notebook where you will also keep all of

your handouts. Many of the handouts given the first grading period will be referred

to all year long. You need to be organized in order to have the information handy

when you need it. Should you lose any handout, you may download another copy

from my website.

Grammar Log (Stylistic Analysis): Research shows that learning grammar in a

vacuum is a meaningless activity. Knowledge of grammar, however, will make you a

better writer. The purpose of the GL is to show your understanding of grammar and

syntax as it relates to what you read and write. The GL is a three-pronged folder with

four dividers. The first page of the GL is the criteria for grading sheet; the same

sheet is used for the whole year. Each area of stylistic analysis will be explained in

class. GRAMMAR CREATES MEANING! This mantra will be proved as you work on

your log! Requirements follow texts.

Essays: You will experience writing as a process (Prewriting, Writing, Revising, and

Editing) with each essay. Essays will be graded using various rubrics (Deiderich, Six

Trait), which will be clearly defined before the rough draft is due. Rough drafts are a

requirement; thus, they will be counted as part of the final draft grade. Each essay

will be written with the entire class (not just me) as the audience in mind; this is

because peer editing “Round Robin” sessions and/or instructor conferences will be

held for each major assignment. The technique of glossing will be fully discussed in

class and is required for all major writing assignment revisions.

AP Exam Review: Practice tests will be used each nine weeks. You will practice with

both timed essay writing and the multiple-choice format. These will be graded using

AP criteria for passing. You will write 3 timed-writes (thematically related to the unit

under study) a grading period for a grade. Samples from released exams will be

evaluated as well to understand the criteria used by readers to score timed-writes.

The following is an explanation of the 18 skills which will be the focus of this course.

Eighteen Essential Skills for AP Language

Word Usage…is consistent, effective, and purposeful word selection. Words are used to

“express” and not “to impress”—and that usage is the most impressive usage of all. The overall

impression is that revision could not likely improve the word usage: different words would be

different—not better; for example: The old yellow photograph exhumed/dredgedup/brought back sad memories for the piece. Exhumed demonstrates an enviable power

with words; dredged-up, an effective power; and brought back, a prosaic one. You know you are

using word skills when you are deciding upon the right word to use for a given situation — and

you get the perfect one.

Word, Phrase and Clause Dynamics…are the creation, definition, analysis, manipulation of

inflectional word forms, the primary phrase structures, the primary clause structures, the

5

modifying elements, the linking elements, the six tenses, and the miscellany of English grammar

and syntax necessary to effectively apply the grammatical and punctuation conventions of

English. You know you are using word, phrase, and clause dynamics when you are trying to

manipulate a word-group to fit a required function.

Punctuation…is the purposeful and conscious (intentional) control of external and internal

punctuation. Using a full range of punctuation—more than just commas—without lapses requires

a greater command of the skill than work which avoids more than commas and end-marks.

Punctuation involves the use of commas, periods, semicolons, colons, dashes, parentheses,

quotation marks, ellipses, and brackets. You know you are using punctuation skills when you

know — it isn’t a guess — where commas, periods, semicolons, colons, dashes, parentheses,

quotation marks, ellipses, and brackets go in a sentence.

Grammar…is the purposeful and conscious control of grammar, with no lapses in grammar

growing out of ignorance of the rules; what few, minor lapses there are seem to be slips of

inattention or, at worst, “word processing” induced errors. Not all grammatical errors are the

same, ranging from Level I minor errors such as faulty comparisons and subordination to Level 4

major ones, such as run-ons, fragments, and spelling errors. You know you are using grammar

skills when you can revise your work for grammatical errors by identifying and correcting errors

such as comma splices, diction, dangling introductory elements, fragments, faulty comparisons,

faulty subordination, incorrect cases, misplaced adjectivals and adverbials, misplaced

correlatives, noun-antecedent agreements, pronoun-antecedent agreements, predicate mood

errors, part of speech errors, parallel structure errors, pronoun reference, redundancies,

restrictive / nonrestrictive punctuation errors, run-ons, reflexive pronoun errors, subject-predicate

agreements, split infinitives, tense sequences, and verb form errors.

Sentence Crafting…is the effective blending of phrase and clause structures so that complex

ideas create and sustain a smooth rhetorical flow, such that there is no obvious way—perhaps

even subtle way—to improve the sequence and flow of the phrases and clauses. The writer

displays a command of sentence crafting/combining that is effective, purposeful, and intentional:

purpose determines the forms, rhythms, etc. In less effective sentence crafting, stronger

subordination is often absent: revision could effectively reduce and tighten the structure. You

know you are using sentence crafting skills when you are combining and/or transforming your

sentences for a specific, conscious purpose, such as (1) to add variety, or (2) to sustain a smooth

flow, or (3) to create a certain rhythm.

Paragraph Crafting…is the creation of paragraphs with the following strengths:

Unity. Focused on one point

Sequence. Clear and effective order

Transition. A strong, uninterrupted flow

Development. Primary evidence, full argumentation, elaboration not assertion,

appropriate scale

You know you are using paragraph crafting skills when you know that you are writing a sentence

because it (1) keeps the paragraph focused on the point, (2) provides a logical arrangement to

the paragraph, (3) aids the readers in traveling through your paragraph, and/or (4) proves the

necessary examples and explanation to develop your idea.

Rhetoric…is the composition of effective introductions, body paragraphs, and conclusions. It is

the resolution of the “critical question” or prompt of a writing with an articulated critical

argument—judging when and how to elaborate in critical arguments and incorporating a

“resolution sequence” to resolve the thesis. You know you are using rhetorical skills when you

construct the necessary elements of the given rhetorical element, as when you create “the

introductory quote” for the setting-the-scene introduction.

Writing Style…is the application of the style rules in revision. As Strunk and White tell us,

“Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no

6

unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines

and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences

short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell” (23).

You know you are using writing style skills when you revise your writing with the Strunk and White

prescriptions in mind, when you change your writing to create a noticeable “turn-of-the-phrase,”

when you try to evoke a specific reader response with your phrasings, when you revise in an

effort to be more direct and forceful, when you write so that a reader can see exactly what you

see. It is indeed the effort to be concise, but it is also the effort to be precise. It is the difference

between “Man, my dad was mad!” and “Man, my dad’s face turned bright, bright red, and he

opened his mouth to scream, only nothing came out, just grunts, grunt after grunt, his whole body

shaking, his arm reaching out to take hold of my neck…”

Writing • Genre and Processes…is the composition of example essays, critical reviews, essays

of literary interpretation, “loops of critical argument,” paragraphs, paraphrases of

readings/viewings, research papers, and the like. It is the projection and planning of an essay,

and its drafting, revision, proofing, and final publication. One’s writing possesses a personal,

distinctive, identifiable voice and the characteristics of effective writing: focus, organization, style,

content, and convention — in both in-class and out-of-class writings, timed and untimed. You

know you are writing genre and processes skills when you know and employ pre-writing, drafting,

revision, proofreading, and final publishing strategies.

Listening and Viewing Skills…involve effectively following directions and the flow of

discussions, conversations, and lectures — the recognition of errors and lapses in these listening

events, duly noting significant points, and demonstrating short- and long-term recall. You know

you are using listening skills when you consciously attend to what you are being told with a

specific purpose in mind, as when you listen to your peers in a Socratic Seminar in order to

respond intelligently, a lecture to take the relevant notes, or you listen to instructions so you can

follow the directions. You know you are a discriminate viewer when you can recognize

manipulation of white space, use of color, focal point, and perspective.

Reading and Viewing Comprehension…is the attentive, retentive, imaginative grasp of the

literal text of the story, essay, drama, poem, novel, or text. It is the recognition of which words,

lines, and passages are significant and telling. You know you are using comprehension skills

when you can recall / paraphrase the words, lines, and passages necessary for a full literal and

analytical grasp of the text.

Speaking Skills…is the ability to speak with these guidelines in mind: (1) project your voice; (2)

enunciate clearly; (3) modulate tone and pacing; (4) use appropriate syntax and sentence

structure; (5) use proper posture, comportment, and movement; (6) use props in an effort to

improve a presentation. You know you are using speaking skills when you gain and hold an

audience’s attention with a conscious control and command of the guidelines mentioned above.

Critical Thinking Skills…is the bringing of detail, nuance, subtlety, distinction, differentiation,

discrimination, and the like to conscious awareness and judgment. It is, further, the purposeful

imposition and/or recognition of design, intent, or arrangement. Critical Thinking, in essence,

embodies analysis, synthesis, and evaluation You know you are using critical thinking skills when

you are looking at something — a text, a question, your own writing — and you need to bring to

the surface its design (what do all these poetic metaphoric associations have in common?), its

arrangement (how do I sequence these examples in my essay?), its quality (what grade do I give

grammar in the peer review?), its intent (what is the purpose of this sentence in this essay?—

what is it trying to prove?). In a sense, critical thinking is the “thinking” that makes your head hurt,

the thinking that is used to derive answers that cannot be memorized. With critical thinking, you

analyze data/text, create something original from that analysis, and then evaluate the final

product based on specific criteria.

7

Interpretation Skills…is the application of a literary measure — irony, for example — to a text in

order to make a point that has the following characteristics:

Beyond literal. You say something about a text. What you say isn’t a summary or

retelling but is beyond the literal.

Supportable. It isn’t at odds with the facts of the book; it can be supported and proven

by the text and/or logical arguments.

Debatable. It isn’t needlessly obvious; it goes out on a "limb of commitment" by

suggesting a point that can be debated.

Central significance. Really good interpretations go further. In these, the point isn’t

peripheral; it is of central significance.

Depth and insight. The point doesn’t leave more to be said; it displays as much depth

and insight as can be reasonably be expected for someone at the given course/grade level.

Expressed forcefully. The point isn’t expressed weakly; it makes its impact with full

force and power.

Interpretation strategies include those related to genre, cultural influences, literary merit, setting,

themes, characters, ideas, literary devices, tone, ambiguities, subtleties, contradictions, ironies,

nuances, point-of-view, author’s stance, literary craft within a text or between and among texts.

You know you are using interpretation skills when you apply a learned measure — that irony, for

example, is a contrast between what you expect to happen and what happens — to a text —

Kino, in Steinbeck’s “The Pearl” loses everything after finding the Pearl of the World — to make a

point: that there is irony in the outcome of Kino’s gaining the Pearl that should give him

everything—everything is taken away.

The Thesis Statement…is the creation of a point of interpretation that adheres to the structural

requirements of a thesis—context portion, general thesis, and — if necessary — the qualifying

portion. In addition, the phrasing of the thesis has some personal touch, transformation, injection

of “voice,” or the like that not only makes the thesis a “great point” but also a well-phrased one.

You know you are using thesis statement skills when you create a point of interpretation so that

the reader knows (1) what it is you are interpreting, (2) what your interpretation is, and (3) how

you arrived at such an interpretation. Also, you have injected some “style” so that the expression

of this idea is concise, precise, and vivid to the reader.

Research…finding, judging, and using articles, scholarship, research, and the like — and

transforming such text into the creation and voice of one’s own. It involves effective note-taking of

materials from a variety of print, electronic, and other sources, the integration of direct and

indirect quotes and the corresponding citations, and the composition of “works cited” pages and

annotated footnotes. You know you are using research skills when you are bringing outside

references into your own writing, judging what relevant information to use, transforming the text

into your own voice, integrating and revising the text for grammar and style, and creating the

necessary citations, footnotes, and works cited pages.

Information –Technology…is the use of the personal computer and relevant software to

complete specified assignments. You know you are using information-technology skills when you

can use all the software tools at your disposal for the planning, drafting, revising, and final

publishing of your work. You know how to judge an Internet site as reliable when collecting

information for analysis. You can access a web page.

Work Performance…is the display and organization necessary for developing enduring

language arts skills. You know you are using work skills when you consistently meet both the

letter of the assignment and the deadline.

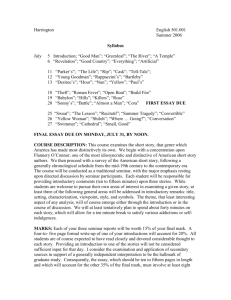

Curriculum

8

All of the thematic units operate with the following common goals: 1identify and discuss

connections among the readings from the unit concerning mode, author’s purpose, main

idea, and essential rhetorical strategies and literary devices which point to the tone and

author’s attitude about the topic, 2recognize differing views about the topic and compare

and contrast these views and 3listen attentively to and evaluate peer responses for content

and presentation.

A note on texts: All students are required to purchase (talk to previous years’ students

about purchasing used tests) The Jungle and Amusing Ourselves to Death (any edition) –

these two texts will be used extensively and you will need to write in them. You may

purchase new or used or use a media center copy of either Nickle and Dimed or Fast

Food Nation. All other texts listed will be provided in class for check-out.

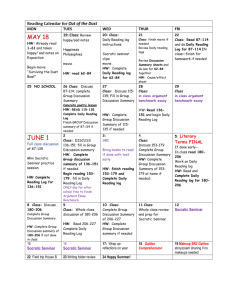

QUARTER ONE

Major Assignments (When applicable, full explanations follow listing of texts):

Orientation/Overview of Course

Summer Reading Assessment: The Jungle and Amusing Ourselves to Death

Summer Reading Long Form: Fast Food Nation or Nickle and Dimed

Tone Illumination Project

Advertisement Project

Comic Project

Personal Narrative Essay

Socratic Seminar #1 and #2 (Amusing Ourselves)

Everyday Use

Chapter 1: Rhetoric in our Lives

Chapter 2: Five Traditional Canons of Rhetoric

Thematic Units * texts in each unit follow Curriculum: 1Beginnings: Rhetoric and an

Album of Styles; 2On Writers and Writing; 3Personal Reflections; 4Advertising and

Popular Culture (multi-source synthesis timed-write example provided following

texts)

Longer Work: Of Mice and Men (analysis of diction, concision, rhetorical

strategies; historical context)

QUARTER TWO

Major Assignments **:

Columnist Project

Editorial Cartoon Project

Persuasive letter

Editorial on topic of choice

Outside Reading: Nonfiction independent reading choice – Long Form

(explanation follows texts) due Quarter Three

Inside/Outside Circle Seminar (Gender Wars)

9

Socratic Seminar #3 (Amusing Ourselves)

Everyday Use

Chapter 3: Rhetoric and the Writer

Chapter 4: Rhetoric and the Reader

Thematic Units *: 1Persuasion and Argument; 2Gender Wars

Longer Work: The Crucible (analysis of diction; argumentation strategies;

fallacies; historical context)

QUARTER THREE

Major Assignments **:

Long Form – nonfiction independent reading choice

Researched Argument paper

Socratic Seminar #4 (Tisdale, Hemingway, and Hegland)

Fish Bowl discussion (Death and Dying)

Everyday Use

Chapter 5: Readers as Writers, Writers as Readers

Thematic Units *: 1Death and Dying; 2A Discourse on Science; 3On Being

Different: “Isms” and the Distinct American Culture

QUARTER FOUR

Major Assignments **:

REHUGO (explanation follows texts)

Compare/Contrast Essay (Allegory of the Cave and The Matrix)

Socratic Seminar #5 (War)

Personal “Declaration of Independence” (imitation writing)

AP Language and Composition Examination Preparation

Thematic Units *: 1War as a Biological Phenomenon; 2Truth and Belief:

3Nonconformity and Transcendentalist Thought; 4Film as Literature: A Study in

Classic Film Technique

Because we will be viewing several films rated PG-13 and R, a parental

permission slip will be required for the Film Unit. We will view several Hitchcock

films (Psycho, The Birds, and Rear Window) to study technique. Then we will

view The Matrix in conjunction with a study of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Time

permitting we will also view any or all of the following: Twelve Angry Men, Dead

Man Walking, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Citizen Kane.

Everyday Use

Chapter 6: Rhetoric in Narrative

10

Longer Work (choice):

The Scarlet Letter

Huckleberry Finn

The Great Gatsby

Passage parsing and explication paragraph; “grammar creates meaning”

passage; diction analysis; historical perspective

Unit Selections: Thematic Essays and Short Stories

From Norton Reader (N) and Bedford (B)and other sources listed (HO) in Bibliography

An Album of Styles

E. B. White

In an Elevator; New York (HO)

Surfing (HO)

Rocky Shores (HO)

Mark Twain

Luck (HO)

Roger Ansell

The Baseball (HO)

Edmund Wilson

American Earthquake (HO)

Bruno Bettelheim

A Victim (N)

Kingsolver

Want (HO)

Lewis Carroll

Jabborwocky (HO)

Hemingway excerpts (HO)

Wallace Stegner

Coming Home (HO)

Queen Victoria at the End of Her Life (HO)

Abraham Lincoln

Gettsyburg Address (N)

John Updike

My Grandmother (HO)

E.B. White

Boston excerpt (HO)

Sean O’Casey

excerpt (HO)

Major Speeches: Faulkner, Kennedy, Angelou, Lincoln, MLK (HO)

On Writers and Writing

Wayne C. Booth

Boring from Within: The Art of the Freshman Essay (N)

Lewis Thomas

Notes on Punctuation (N)

George Orwell

Politics and the English Language (N)

Eudora Welty

One Writer’s Beginnings (N)

Stephen Greenblatt

Storytelling (N)

Adrienne Rich

When We Dead Awaken: Writing as Re-Vision (N)

Virginia Woolf

In Search of a Room of One’s Own (N)

Kurt Vonnegut

How to Write with Style (HO)

“College Faculty Expectations…” (HO)

Paul Robinson

The Philosophy of Punctuation (HO)

Barbara Mellix

From Outside, In (HO)

Frederick Douglass

Learning to Read (HO)

John Jordan

Rhetoric (HO)

Loren Eisley

What Makes a Writer (HO)

Mark Twain

The Art of Composition (HO)

John Ciardi

What Every Writer Must Learn (HO)

E.B. White

Reflections on Writing Charlotte’s Web (HO)

Choosing a Voice (Chapter 4 HO)

Personal Reflections

11

Maya Angelou

Lars Eighner

Alice Walker

E.B. White

George Orwell

Jamaica Kincaid

Gary Soto

Zora Neale Hurston

Dick Gregory

Al Capp

EricSevareid

NancyMairs

Edward Hoagland

Rosemary L. Bray

Aldous Huxley

Toni Cede Bambara

Graduation (N)

On Dumpster Diving (N)

Beauty: When the Other Dancer is Self (N)

Once More to the Lake (N)

Shooting an Elephant (N)

A Small Island (B)

Black Hair (B)

How It Feels to Be Colored Me (HO)

Not Poor, Just Broke (H)

My Well-Balanced Life on a Wooden Leg (HO)

The Dark of the Moon (Ho)

On Being a Cripple (N)

In the Toils of the Law (HO)

So How Did I Get Here (HO)

Meditation on the Moon (HO)

The Lesson (HO)

Death and Dying

Lewis Thomas

The Long Habit (N)

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

On the Fear of Death (N)

Hegland

The Fourth Month (HO)

Stephen Jay Gould

Our Allotted Lifetimes (N)

Rita Moir

Leave Taking (N)

Barbara Huttmann

A Crime of Compassion (N)

Virginia Woolf

The Death of the Moth (N)

Jessica Mitford

Behind the Formaldehyde Curtain (B)

Hemingway

Hills Like White Elephants

Thomas Lynch

Burying

Christine Mitchell

When Living is a Fate Worse than Death (HO)

George Orwell

A Hanging (N)

Randy Wayne White

The Legend (HO)

N. Scott Momaday

On the Way to Rainy Mountain (N)

Sallie Tisdale

We Do Abortions Here: A Nurse’s Story (N)

Stephen Buckley

African Funerals (HO)

Carol Bernstein Perry

A Good Death (HO)

James Joyce

Hell (HO)

Traditions and Myths from Various Cultures (FF)

Gender Wars

Scott Russell Sanders

Anna Quindlen

Herb Goldberg

Betty Rollin

Susan Allen Toth

Judy Brady

Judith Ortiz Cofer

Deborah Tannen

Charles Lamb

Nicholas Wade

Bessie Head

Sei Shonagong

Harriett Davis

Rita Kempley

Dave Barry

Looking at Women (N)

The Men We Carry in Our Minds (B)

Between the Sexes, A Great Divide (N)

In Harness: The Male Condition (N)

Motherhood: Who Needs It? (N)

Going to the Movies (N)

I Want a Wife (B)

The Myth of the Latin Woman: I Just Met a Girl Named Maria (B)

Sex, Lies, and Conversation (HO)

A Bachelor’s Complaint of the Behavior of Married People (HO)

How Men and Women Think (B)

Snapshots of a Wedding (H)

The Pillow Book (HO)

How Not to Raise Our Children (HO)

Abs and the Adolescent (HO)

We’ve Got the Dirt on Guy Brains (HO)

12

Truth and Belief

William Golding

William Gaylin

Langston Hughes

Samuel L. Clemens

Thomas Jefferson

Bruce Agnew

Carl Becker

E.B. White

Lani Guinier

Plato

Jean-Paul Sartre

Robert Lee Stuart

Jonathan Edwards

Rose Shade

Bertrand Russell

Thinking as a Hobby (N)

What You See is the Real You (N)

Salvation (N)

Advice to Youth (N)

The Declaration of Independence (N)

Will We Be One Nation, Indivisible? (HO)

Democracy (N)

Democracy (N)

The Tyranny of the Majority (N)

The Allegory of the Cave (N)

Existentialism (N)

Jonathan Edwards at Enfield (HO)

Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God (HO)

Beauty of the World ( HO)

Puritan Woman (HO)

What Good is Philosophy? (HO)

Nature and Technology

Gretel Ehrlich

Robert Finch

Alexander Petrunkevitch

Chief Seattle

Aldo Leopold

Bill McKibben

Lauren Eiseley

Rachel Carson

Jonathan Schell

John Richards

Joan Didion

Lewis Thomas

James Conant

Spring (N)

Very Like a Whale (N)

The Spider and the Wasp (N)

Letter to President Pierce, 1855 (N)

Thinking Like a Mountain (N)

The End of Nature (B)

Wasps (N)

The Obligation to Endure (HO)

Tides (H)

Our Strange Indifference to Nuclear Power (HO)

How the Spider Spins Its Web (HO)

At the Dam (HO)

The World’s Biggest Membrane (HO)

The Tactics and Strategy of Science (HO)

Nonconformity: Transcendentalist Thought

Thoreau

Emerson

Walden (HO)

Resistance to Government (HO)

Nature (HO)

Self Reliance (HO)

Aphorisms (HO)

Persuasion and Argument

(You will choose an essay**to form the basis of your researched argument essay)

Gerard Jones

Violent Media Is Good for Kids (HO)**

Michael Levin

The Case for Torture (N)

Dorothy Allison

Gun Crazy (N)**

Jonathan Swift

A Modest Proposal (N)

Martin Luther King

Letter from Birmingham Jai l(N)

S.I. Hayakawa

Sex Is Not a Spectator Sport (N)**

Wilbert Rideau

Why Prisons Don’t Work (B)**

Editorial

The Blessings of Slavery (HO)

Paul Goodman

A Proposal to Abolish Grading (HO)**

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

The Communist Manifesto (HO)

13

Adolf Hitler

Aldous Huxley

Patrick Henry

Norman Cousins

Thomas Huxley

Sojourner Truth

Jacob Brownowski

Tom Regan

Terry Tempest Williams

Paul Fussell

Etta Kralovec

The Purpose of Propaganda (HO)

Propaganda Under a Dictatorship (HO)

Speech to the Virginia Convention (HO)

Who Killed Benny Paret? (H)

The Method of Scientific Investigation (HO)

Address to First Annual Meeting of (HO)

The Nature of Scientific Reasoning (HO)

The Case for Animal’s Rights (N)**

The Clan of One-Breasted Women (N)**

Thank God for the Atom Bomb (HO)**

No More Pep Rallies (HO)

Advertising, the Arts, and Popular Culture

John McMurtry

Kill ‘Em! Crush ‘Em! Eat ‘Em Raw!(N)

George Woodcock

The Tyranny of the Clock (N)

Melvin Konner

Why the Reckless Survive (N)

Michael J. Arlen

The Tyranny of the Visual (N)

Aaron Copland

How We Listen (N)

Stephen King

Why We Crave Horror Movies (B)

Emily Prager

Our Barbies, Ourselves (B)

Alex Ross

Generation Exit (B)

James H. Austin

Four Kinds of Chance (HO)

Jon Katz

Interactivity (H)

Tom Shachtman

What’s Wrong with TV Talk Shows? (HO)

David Holahan

Why Did I Ever Play Football? (HO)

Melissa Russell-Ausley and Tom Harris

How the Oscars Work (HO)

On Being Different: “Isms” and the Distinct American Culture

Brent Staples

Jewelle Gomez

Gloria Naylor

Charles R. Lawrence III

Michael Dorris

W.E.B. DuBois

Tamar Lewin

Maxine Hong Kingston

Judith Ortiz Cofer

Alice Adams

Mary Mebane

Eric Liu

Richard Rodriguez

Sara Min

Ralph Ellison

June Jordan

Black Men and Public Space (N)

A Swimming Lesson (N)

Mommy, What Does ‘N’ Mean? (N)

On Racist Speech (B)

Crazy Horse Malt Liquor (B)

The Souls of Black Folk (HO)

Growing Up, Growing Apart (HO)

No Name Woman (HO)

Silent Dancing (HO)

Truth or Consequences (HO)

Shades of Black (HO)

A Chinaman’s Chance: Reflections on the American Dream (HO)

Public and Private Language (HO)

Language Lessons (HO)

On Being the Target of Discrimination (N)

For My American Family (N)

War as a Biological Phenomenon

Henry David Thoreau

Julian Huxley

Margaret Sanger

Samuel L. Clemens

John Hersey

Tim O’Brien

H.L. Mencken

George Schmemann

Jonathan Schell

The Battle of the Ants (HO)

War as a Biological Phenomenon (HO)

The Cause of War (HO)

The War Prayer (HO)

A Noiseless Flash (HO)

Speaking of Courage (HO)

Reflections on War (HO)

To Vietnam and Back. And Back. And Back (HO)

Our Strange Indifference to Nuclear Peril (HO)

14

Additional Resources for Essays and Exercises:

Bell, Kathleen. Writing Choices: Shaping Contexts for Critical Readers. Boston: Allyn

and Bacon, 2001.

Borders, Barbara J., et. Al. Nonfiction: A Critical Approach. Villa Maria, PA: The Center

for Learning, 1994.

Dean, Nancy. Voice Lessons. Gainesville, Florida: Mauphin House, 2000.

Degen, Michael. Crafting Expository Argument. 4th ed. Dallas, Texas: Telemachos

Publishing, 2002.

Diyanni, Robert. Fifty Great Essays. 2nd ed. New York: Pearson Longman, 2005.

Diyanni, Robert and Pat C. Hoy. Frames of Mind: A Rhetorical Reader with Occasions

for Writing. Canada: Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Diyanni, Robert. One Hundred Great Essays. New York: Penguin Academics Longman,

2002.

Goshgarian, Gary. The Contemporary Reader. 8th ed. New York: Pearson Longman,

2005.

Hall, Donald, and D. L. Emblen. A Writer’s Reader. 9th ed. New York: Longman, 2002.

Hirschberg, Stuart and Terry Hirschberg. Reflections on Language. NewYork: Oxford

University Press, 1999.

Holladay, Sylvia A. Bridges: A Reader for Writers. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall,

2006.

Kelly, Joseph (editor). The Seagull Reader. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2002.

Kolln, Martha. Rhetorical Grammar. 3rd ed. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1999.

Levin, Gerald. Prose Models. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1996.

McCuen, Jo Ray and Anthony C. Winkler. Readings for Writers. 10th ed. Fort Worth:

Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 2001.

McWhorter, Kathleen. Seeing the Pattern: Readings for Successful Writing. Boston:

Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2006.

15

Miller, Robert K. The Informed Argument: A Multidisciplinary Reader. Fort Worth:

Harcourt Brace College Publishers, 1998.

Nadell, Judith. The Longman Writer: Rhetoric, Reader Handbook. 6th ed. New York:

Pearson Longman, 2006.

Roorbach, Bill. The Art of Truth: Contemporary Creative Nonfiction. Oxford: Oxford

University Press, 2001.

Ruszkiewicz, John, and Daniel Anderson, and Christy Friend. Beyond Words: Reading

and Writing in a Visual Age. New York: Pearson Longman, 2006.

Shrodes, Caroline, and Harry Finestone and Michael Shugrue. The Conscious Reader. 8th

ed. New York: Longman Press, 2001.

Trimmer, Joseph F. and Maxine Hairston. The Riverside Reader. 6th ed. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999.

Explication of Major Assignments

Grammar Log: Stylistic Analysis

I.

Grammar Notes: All notes given in class. Dates should be included.

II.

Syntactical Log: Locate two examples for each structure you choose, one from published writing and one

from your own writing. Label each by structure and source.

1.

simple sentence

2.

compound sentence by coordination or subordination

3.

complex sentence

4.

compound-complex sentence

5.

sentence fragment

6.

loose sentence (paratactic)

7.

periodic sentence

8.

balanced sentence

9.

short sentence (any type, but label the type)

10. long sentence (at least 20 words; any type, but label the type)

11. sentence with interrupters (any type, but label the type)

12. sentence with unusual punctuation (any type, but label the type)

III.

Syntactical Entries: Write an original example of these types.

1. serial sentence with repetitive parts

2. triadic sentence

3. sentence with parallel structure

4. a loose sentence of at least 20 words

5. a periodic sentence of at least 20 words

6. balanced sentence

IV.

Concision: Rewrite your own sentences to achieve conciseness. Note the source of the original writing.

First, write the original sentence, then the new, concise version. Label each revision.

1. Use a single verb or adjective instead of a phrase.

2. Eliminate awkward anticipatory constructions.

3. Use colon or dash for focus and definition.

4. Use ellipsis in a tightly constructed sentence.

5. Use parallelism to eliminate an extra subject-verb structure.

6. Use a participle to eliminate a prepositional phrase.

16

7.

8.

9.

Eliminate the expletive.

Eliminate the copulating verb.

Eliminate “wordiness phrases” (pp. H139-140, Bedford).

Non-Fiction Book Long Form

The infamous Long Form is your foray into analysis. The first one will be on your

summer reading choice and completed in a small group. The second one will be on a nonfiction book of your choice (with my approval) and will be completed individually.

DICTION: Analyze the author’s word choices. (25)

First discuss the work in general: is the diction informal, formal, neutral, colloquial? Explain and

give an example.

Does the author use much imagery?

Metaphoric and/or ironic devices?

Is the language plain? Flowery? Concise? Strong? Lyrical?

Does diction indicate social status, education, region?

How much dialogue is used? How different is the dialogue from the narrative voice? How distinct

is the dialogue from character to character?

SELECT THREE PASSGES (minimum: approximately one-half page) featuring different plot segments. Copy

the segments and include in your report. Closely (closely!) read the passages, then discuss specifically the

diction. Comment on how diction helps define character, set tone, further theme, etc. (45)

SYNTAX: (word order, pattern) Analysis of sentence and phrase patterns. (20)

Make some general observations: Are the sentences predominately simple or complex?

What about length? Level of formality? Any fragments? Rhetorical questions? Parallel structure?

Repetitions? Are sentences loose, periodic? Is there much variety to the sentence pattern?

How does the author use syntax to create rhythm and flow of the language?

How does the author use syntax to enhance effect and support meaning?

Using one of the same passages from the diction section above, focus on the author’s syntax. What effect

is he/she creating? Comment on how these choices help define character, set tone, further theme, etc. (15)

CONCRETE DETAIL/IMAGERY: Words or phrases that appeal to the five senses – most commonly visual.

Look for recurrent images or motifs. What function does the imagery seem to have? Use direct quotations

from the text to support your observations. Cite chapter/page number. (15)

FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE (TROPES): Language that is not literal. Metaphorical devices link meaning;

most common are METAPHOR, SIMILE, PERSONIFICATION, AND ALLUSION. Point out examples; how

used, how often? Use direct quotations from the text to support. Cite chapter/page number. (15)

TONE: Author’s attitude toward subject, characters, and reader. Could be playful, serious, angry, ironic,

formal, somber, satiric, etc. Generally an author uses a limited variety of tones, often two or three

complementary ones. Discuss the book’s tone and observe how the author creates it through plot, diction,

syntax, imagery, figurative devices. Use direct quotations from text to support observations. (15)

MEMORABLE QUOTES: Select 5 short passages, or sentences, or fragments that capture the essence of

the story and style. Include chapter/page number. Discuss the significance to the work of each selection.

(35)

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE TITLE: Comment of the book’s title. What message does the author want to

convey with the title? Does the meaning of the title change for the reader from pre to post reading? (15)

RESEARCH/LITERARY CRITISM: (25)

Read two critiques or literary reviews. Be sure these come from substantial, reputable sources such as the

New York Times. Los Angeles Times, etc. or academic sources and not just Cliffs Notes or just some guy on

the internet who thinks he knows what’s he’s talking about. You must choose PRIMARY SOURCES! Read and

digest the information and write a short summary of what you gained from the reading. Please note that

you are summarizing your reaction to the article, not the article itself. For example, you might want to

17

think in terms of “three important insights” you gained from each. Include as an attachment to the

bibliography a copy of each article that shows your notes, highlighting, etc.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS: (15)

Did you enjoy the book?

Strengths, weaknesses, lingering questions?

Does it relate to other books you have read?

Any insights into human folly or triumph?

Do you expect any lasting effects on you?

Don’t underestimate the importance of this last section!

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Attach a bibliography of any outside sources you use. Use MLA format. (10)

REHUGO PROJECT

The REHUGO project will be explained during the first grading period but is not due

until April. The purpose of the project is for you to show me the steps you have taken to

become a “Citizen Rhetor.” REHUGO becomes the portfolio of your experiences outside

of the classroom. Specific parameters will be discussed in class. The following is a brief

overview of the requirements.

Reading: Read a book not related to an assignment in school. Read something you have

not read before and write an opinion on it.

Entertainment: 4 events with response and Universal Truth. Choose a play, a museum, a

“classical” musical event and a free choice. Go, experience it, and then find a universal

truth you discovered – about the event, about people, whatever. The free choice is pretty

much wide-open. Past choices have included a garage sale, a monster truck pull, a pop

concert (or rock or country or whatever).

History: Choose 3 events you believe to be the most critical and explain why with

support.

Universal Truth: Write about any 3 deep thoughts.

Government: Follow a city, county, or state local improvement issue. Once you have

followed it, offer your solution. This issue must be local – national and international

events are not acceptable.

Observation: Watch your friends. Observe the hallways during class changes. Listen at

lunch. Describe any 3 trends in current culture you have noticed and provide concrete

evidence.

Tone Illumination Project

Because tone can be difficult to identify and describe, beginning with a working

vocabulary can be helpful. You will choose any ten words from the list given in class.

Cite source of definition (use MLA format). Each tone word should be on a separate

page. The tone word should be large enough to be seen from the desks across the room.

Use visual images as well as synonyms to define your tone word. Your final page will

resemble a collage of images and words that illuminate that particular tone word. For

example: Along with a formal definition, the word “Somber” might be depicted with

pictures of people lighting candles at a memorial. You might include a picture of soldiers

at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Words that might be included are: solemn, grave,

18

sad, serious, glum, grim, and staid. Each grading period we will change the words posted

on the walls.

Advertising Project

Using the “Tools for Advertising Analysis” handout, choose five advertisements that

display a total of 20 different strategies. Advertisement selection can come from a variety

of sources – print, television, radio among them. You will present your advertising

portfolio to a small group. Each group will then select a sample of 3 advertisements from

the group to share with the whole class. DVD player, VCR , and CD player will be shared

on a rotating basis.

Specific Tools for Advertising Analysis: Techniques of Persuasion

1. Symbols are larger than reality, usually emotional, idea-conveyances: symbols can be words,

designs, places, ideas, music, etc. They can symbolize tradition, nationalism, power, religion, sex

or any emotional concept. The fundamental principle of persuasion is to rub the emotional

content of one thing onto another. Thus, a beautiful woman can be used on TV to promote lust,

romance, killing of police, or Snickers’ nutrition.

2. Hyperbole is exaggeration or “hype.” Glittering generalities is a subset of hype that utilizes

impressive language. Vague and meaningless, it leaves the target impressed emotionally and,

therefore, more susceptible to the next sales pitch. For example, “The greatest automobile

advance of the century. . . .”

3. Defensive Nationalism uses fear (usually of an enemy) although it can be a political

opponent, sickness, or any threat. For example, calling statements “McCarthyism” or

“communism” brings up fear of demagogues and dictatorship. Scapegoating is a powerful subset

of defensive nationalism that blames many problems upon one person, group, race, religion, etc.

4. Humor is a powerful emotion. If you can make people laugh, you can persuade them.

5. Lie (big): Most people want to believe what they see. Lies work, on cereal boxes, ads, and on

television “news.” According to Hitler, people are more suspicious of a small lie than a large one.

6. Maybe: Outrageous claims are fine, if preceded by “maybe, might, or could.” Listen to the

infomercials.

7. Testimonial uses famous people or respected institutions to sell a person, idea, or product.

They need have nothing in common. A dangerous trend: we seem to be increasingly conditioned

to accept illogic as fact.

8. Repetition drives the message home many times. Even unpleasant ads work. Chevy trucks

are “like a rock,” and smoking Marlboro can make you tough and independent (Fact: it used to

be a cigarette for girls.)

9. Plain folks promotes oneself or one’s product as being of humble origins, common—one of

the gals/guys. It is very popular with advertisers and politicians. Unfortunately, plain folks

reinforces anti-intellectualism (a common tendency of all electronic media), implying that to be

“common” is good (an’ hit ain’t, dude, ya know?).

19

10. Fuhrerprinzip (first used by Josef Goebbels) means “leadership principle.” Be firm, bold,

strong; have dramatic confidence, frequently combined with plain folks. Many cultural icons

emphasize the strong, yet plain, superhero (Clint Eastwood, Bruce Willis, Segal, Schwartznegger.

. .). Some think this role modeling leads to a great deal of male “aloneness,” and, perhaps, less

ability to cooperate.

11. Name calling or ad hominem is frequent. It can be direct or delicately indirect. Audiences

love it. Our violent, aggressive, sexual media teaches us from an early age to love to hear dirt.

(Just tune in to afternoon talk TV.) Name calling is frequently combined with hype, truth, lies,

etc. Remember, all is fair in love, war, political dirty tricks, and advertising—and suing for libel

is next to impossible!

12. Flattery is telling or implying that your target is something that makes them feel good or,

often, what they want to be. And, I’m sure that someone as brilliant as yourself will easily

understand this technique.

13. Bribery seems to give something desirable. We humans tend to be greedy. Buy a taco; get

free fries.

14. Diversion seems to tackle a problem or issue, but, then, throws in an emotional non-sequitur

or distraction. Straw man is a subset that builds up an illogical (or deliberately damaged) idea

which one presents as something that one’s opposition supports or represents. Then one proceeds

to attack this idea, reducing one’s opponent.

15. Denial: Avoid attachment to unpopular things; can direct or indirect. My favorite example

of indirect denial was when Dukakis said, “Now I could use George Bush’s Willie Horton

tactics* and talk about a furloughed federal (the President’s jurisdiction) prisoner brutally raped a

mother of five children, but I would not do that.”

16. Card Stacking is to provide a false context, so that they give a false and/or misleading

impression—telling only part of the story. Read the quotations from the critic in any movie ad.

17. Band wagon insists that “everyone is doing it.” It plays upon the universal loneliness of

humankind. In America with our incredible addiction to sports, it is often accompanied by the

concept of winning. “Wear Marlboro ‘gear’.”

18. Simple solutions: Avoid complexities (unless selling to intellectuals). Attach many

problems to one solution.

19. Scientific evidence uses the paraphernalia of science (charts, etc.) for “proof” which, of

course, often is bogus. A classic example is Chevy’s truck commercial chart of vehicles on the

road after ten years.

20. Group Dynamics replaces that “I” weakness with “we” strength. Concert, audiences, rallies,

pep rallies. . . .

21. Rhetorical questions get the target “agreeing,” saying “yes,” building trust; then try to sell

them.

22. Nostalgia: People forget the bad of the past. Thus, a nostalgic setting makes a product

“better.” Forrest Gump!

20

23. Timing can be as simple as planning your sell for when your target is tired. In sophisticated

propaganda it is the organization of multiple techniques in a pattern or “strategy” which increases

the emotional impact of the sell.

*** The following is a model of the synthesis question on the AP Exam you will take in

May. Since this is the first year the question will be asked, the model is my best guess of

what one will look like. This one will follow the Advertising and Pop Culture thematic

unit. I include it so that you can anticipate how closely you need to examine the ads you

choose for your project.

Synthesis Question: Advertising

Directions: The following prompt is based on the accompanying six sources.

This question requires you to integrate a variety of sources into a coherent, wellwritten essay. Refer to the sources to support your position; avoid mere paraphrase or

summary. Your argument should be central; the sources should support your

argument.

Remember to attribute both direct and indirect citations (Note: choose one method of

citation and be consistent; sources other than given will not count! Don’t use the

movie you saw over the week-end!)

Introduction

Aldous Huxley claims that “The advertisement is one of the most interesting and difficult

of modern literary forms.” Is he right? Advertising is a symbol manipulating occupation

whose sole purpose is to persuade the consumer to buy a product or an idea. In the course

of persuasion, advertisers deliberately use language that makes a variety of appeals, and

language and visuals that use a variety of rhetorical strategies. These strategies range

from the simple to the complex. Are some strategies more effective than others? Why?

What strategies most sway you?

Assignment

Read the following sources (including any introductory information) carefully. Then in

an essay that synthesizes at least three of the sources for support, take a position that

defends, challenges, or qualifies the claim that one of the provided advertisements is

more persuasive than the others with its manipulation of symbols and/or language.

Refer to the following sources:

Source A: O’Neill

Source B: Clegg

Source C: Bordo

Source D: Ruszkiewicz, et.al.

Source E: Obesity advertisement

21

Source F: Got Milk advertisement

Columnist Project

You will be required to follow a national columnist in a newspaper or weekly magazine. You must

collect six current, consecutive columns by your author. Choose your columnist early; there is a

limit to the number of students per columnist. Periodical web sites can be easily accessed on the

Internet; all can be accessed in school or at home. You may find the name of the specific author

you wish to follow on the home page; otherwise, check the Editorials or Op-Ed. Archives can be

searched on these sites, but many publications require payment for articles older than one or

two weeks. Therefore, do not let this go until the due date. I encourage you to communicate with

your columnist. Ask questions. Check the newspaper or magazine for the appropriate contact

information (especially e-mail).

The project has three parts:

I. Each article must be ANNOTATED as we have practiced in class (colors with legend). Annotate

for the following:

Speaker's tone (a must!)

Rhetorical strategies

Organizational shifts

Appeals to logic or emotion

Mark places in the text that evoke a reaction from you, be it laughter, anger, or confusion.

II. After annotating, write a ONE-PAGE RESPONSE (maximum; 12 Point Times New Roman;

single spaced) that includes the following:

A brief summary of the author's main point

The most salient strategies employed by the author

The article's effect on you

Your FIRST annotated article and one-page response are due seven school days from today; if

you are struggling I can then give you some guidance. I will not check the next five articles and

responses; they are due with the final assignment.

III. The final task is to write A SYNTHESIS ESSAY that delineates the following:

The author's general focus in columns (e.g. political, family, arts)

Three of the author's oft-used stylistic devices

An analysis of the efficacy of those devices

You are to judge the author's writing style as convincing or ineffectual and explain why; it is not

necessary that you agree with the author if you feel s/he has made a point forcefully. Specific

examples must be provided from a variety of collected columns.

1. Length of final essay should be between one and a half and two pages (maximum), 12 point

Times New Roman font + a third page for your Works Cited information. The essay should be

single- spaced.

Remember that a Works Cited page should be headed by the centered words "Works Cited and

Consulted" (without the quotation marks); this heading will allow you to simply cite all six

editorials-in proper MLA form-beginning with your columnist (last name first) and followed by each

column's title (in quotation marks-punctuation INSIDE the quotation marks! MINUS 10 POINTS

FOR EACH INCORRECT USE OF QUOTATION MARKS.)

22

2. You should freely refer to the editorials as a whole. Presume your reader is looking at your six

editorials and has read them. If you quote (preferably embedded) words, phrases, or lines from a

specific editorial, follow the procedure of enclosing an abbreviated version of the title of the

editorial in parentheses. I would like to see two to four internal citations for three reasons: (1) to

show you know the citation form, (2) to show you know how to gracefully incorporate quotations,

and (3) to allow you to reinforce the validity of your argument by referring to "proof." (I expect you

to include specific examples in the body of your essay as your discuss various stylistic devices.).

3. This is a formal essay. You should write in the third person (avoiding the passive) except for

the last paragraph in which you might shift to first person when you evaluate the readability of the

columnist and explain your personal response to his/her style, perspective, and topics.

4. This is an analytical essay and a research paper based entirely on primary resources (your six

columns). Remember George Orwell as you avoid empty phrases, clichés, jargon, and

obfuscation.

Comic Project: You will scour the comics (a tough assignment) looking for interesting

applications of grammar, language manipulation (e.g. puns, malapropisms), colloquialisms,

dialect, and/or spelling. Collect 5 examples and mount them on construction paper. These will be

displayed on the “Isn’t Language Funny?” bulletin board in class on a rotating basis.

Editorial Cartoon and Editorial writing: While we are in the Argument and Persuasion

unit and based upon your topic choice, you will find an editorial cartoon to illustrate an editorial

you write about your chosen topic. Sources for cartoons will be discussed in class.

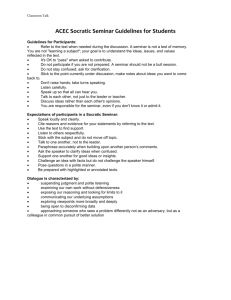

Socratic Seminar (http://www.lacoe.edu/pdc/professional/socratic.html)

You will participate in Socratic Seminars throughout the year. What follows is an explanation of

expectations for your participation. Seminars are 50 points for the first semester. They are 100

points for the second semester.

WHAT DOES SOCRATIC MEAN?

Socratic comes from the name Socrates. Socrates (ca. 470-399 B.C.) was a Classical Greek

philosopher who developed a Theory of Knowledge. He was an Athenian philosopher born in 469 BC and

is known today thanks to the writings of his most famous pupil, Plato. Socrates neglected his own affairs

choosing, instead, to spend his time organizing public gatherings to discuss virtue and justice. He is

credited with formulating a method of discussion known as the Socratic dialectic. Encouraging participants

to sit in a circle, Socrates would draw knowledge from the group by presenting a series of deeply

philosophical questions. Socrates looked on the soul as the heart of consciousness and moral character and

believed that each person needed to understand his/her own "true self." While Socrates was a gentle spirit,

he made numerous enemies. His thoughtful critiques of the Athenian religious and political institutions

were considered acts of heresy. He was eventually tried for corrupting the beliefs and values of Athenian

youths. Following his conviction in 399 BC, he willingly drank the cup of hemlock that was given to him.

WHAT WAS SOCRATES' THEORY OF KNOWLEDGE?

Socrates was convinced that the surest way to attain reliable knowledge was through the practice of

disciplined conversation. He called this method dialectic.

What does dialectic mean?

Di-a-lec-tic (noun) means the art or practice of examining opinions or ideas logically, often by the

method of question and answer, so as to determine their validity.

How did Socrates use the dialectic?

He would begin with a discussion of the obvious aspects of any problem. Socrates believed that

through the process of dialogue, where all parties to the conversation were forced to clarify their ideas, the

final outcome of the conversation would be a clear statement of what was meant. The technique appears

simple but it is intensely rigorous. Socrates would feign ignorance about a subject and try to draw out from

the other person his fullest possible knowledge about it. His assumption was that by progressively

correcting incomplete or inaccurate notions, one could coax the truth out of anyone. The basis for this

assumption was an individual's capacity for recognizing lurking contradictions. If the human mind was

23

incapable of knowing something, Socrates wanted to demonstrate that, too. Some dialogues, therefore, end

inconclusively.

What is a Socratic Seminar?

A Socratic Seminar is method to try to understand information by creating a dialectic in class in

regards to a specific text. In a Socratic Seminar, participants seek deeper understanding of complex ideas in

the text through rigorously thoughtful dialogue, rather than by memorizing bits of information. A seminar

consists of four elements:

The text - Can come from any subject area.

The question - Reflects genuine curiosity and has no "right" answer.

The leader - Offers the initial question then plays a dual role as leader and participant.

The participants - Study the text in advance, listen actively, and share ideas using evidence from the text

for support.

The Text: Socratic Seminar texts are chosen for their richness in ideas, issues, and values and their

ability to stimulate extended, thoughtful dialogue. A seminar text can be drawn from readings in

literature, history, science, math, health, and philosophy or from works of art or music. A good text

raises important questions in the participants' minds, questions for which there are no right or wrong

answers. At the end of a successful Socratic Seminar participants often leave with more questions than

they brought with them.

The Question: A Socratic Seminar opens with a question either posed by the leader or solicited from

participants as they acquire more experience in seminars. An opening question has no right answer,

instead it reflects a genuine curiosity on the part of the questioner. A good opening question leads

participants back to the text as they speculate, evaluate, define, and clarify the issues involved.

Responses to the opening question generate new questions from the leader and participants, leading to

new responses. In this way, the line of inquiry in a Socratic Seminar evolves on the spot rather than

being pre-determined by the leader.

The Leader: In a Socratic Seminar, the leader plays a dual role as leader and participant. The seminar

leader consciously demonstrates habits of mind that lead to a thoughtful exploration of the ideas in the

text by keeping the discussion focused on the text, asking follow-up questions, helping participants

clarify their positions when arguments become confused, and involving reluctant participants while

restraining their more vocal peers. As a seminar participant, the leader actively engages in the group's

exploration of the text. To do this effectively, the leader must know the text well enough to anticipate

varied interpretations and recognize important possibilities in each. The leader must also be patient

enough to allow participants' understandings to evolve and be willing to help participants explore nontraditional insights and unexpected interpretations. Assuming this dual role of leader and participant is

easier if the opening question is one which truly interests the leader as well as the participants.

The Participants: In a Socratic Seminar, participants carry the burden of responsibility for the quality

of the seminar. Good seminars occur when participants study the text closely in advance, listen

actively, share their ideas and questions in response to the ideas and questions of others, and search for

evidence in the text to support their ideas. Eventually, when participants realize that the leader is not

looking for right answers but is encouraging them to think out load and to exchange ideas openly, they

discover the excitement of exploring important issues through shared inquiry. This excitement creates

willing participants, eager to examine ideas in a rigorous, thoughtful manner.

Guidelines for Participants in a Socratic Seminar

1. Refer to the text when needed during the discussion. A seminar is not a test of memory. You are not

"learning a subject"; your goal is to understand the ideas, issues, and values reflected in the text.

2. It's OK to "pass" when asked to contribute.

3. Do not participate if you are not prepared. A seminar should not be a bull session.

4. Do not stay confused; ask for clarification.

5. Stick to the point currently under discussion; make notes about ideas you want to come back to.

6. Don't raise hands; take turns speaking.

7. Listen carefully.

8. Speak up so that all can hear you.

9. Talk to each other, not to me.

10. Discuss ideas rather than each other's opinions.

11. You are responsible for the seminar, even if you don't know it or admit it.