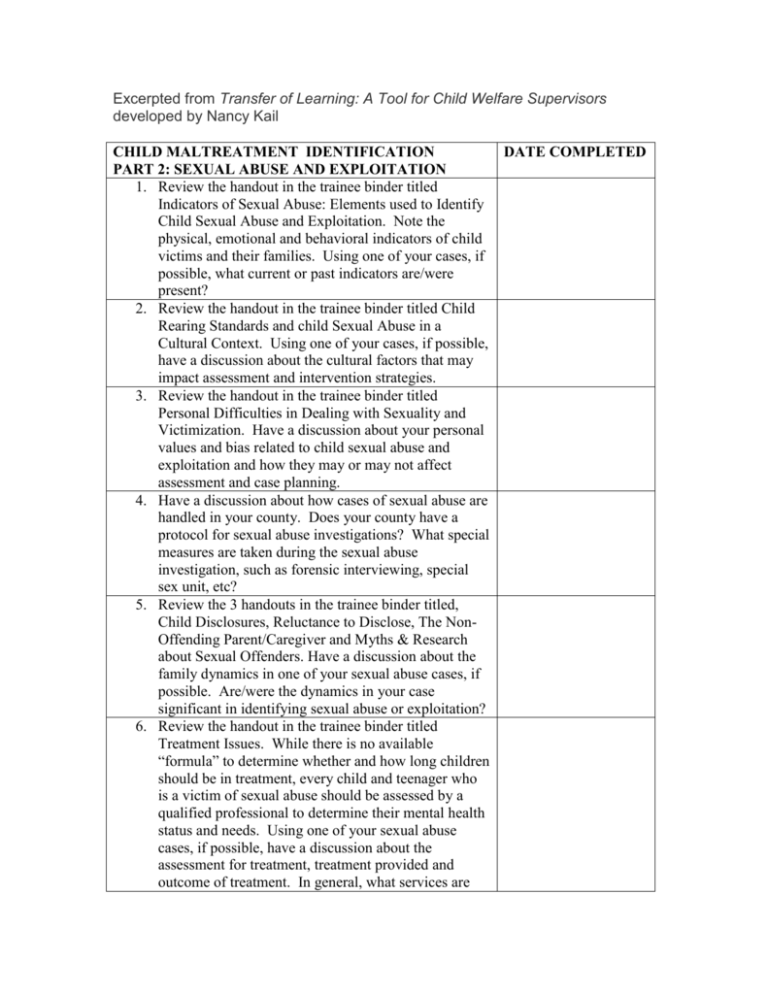

Excerpted from Transfer of Learning: A Tool for Child Welfare Supervisors

developed by Nancy Kail

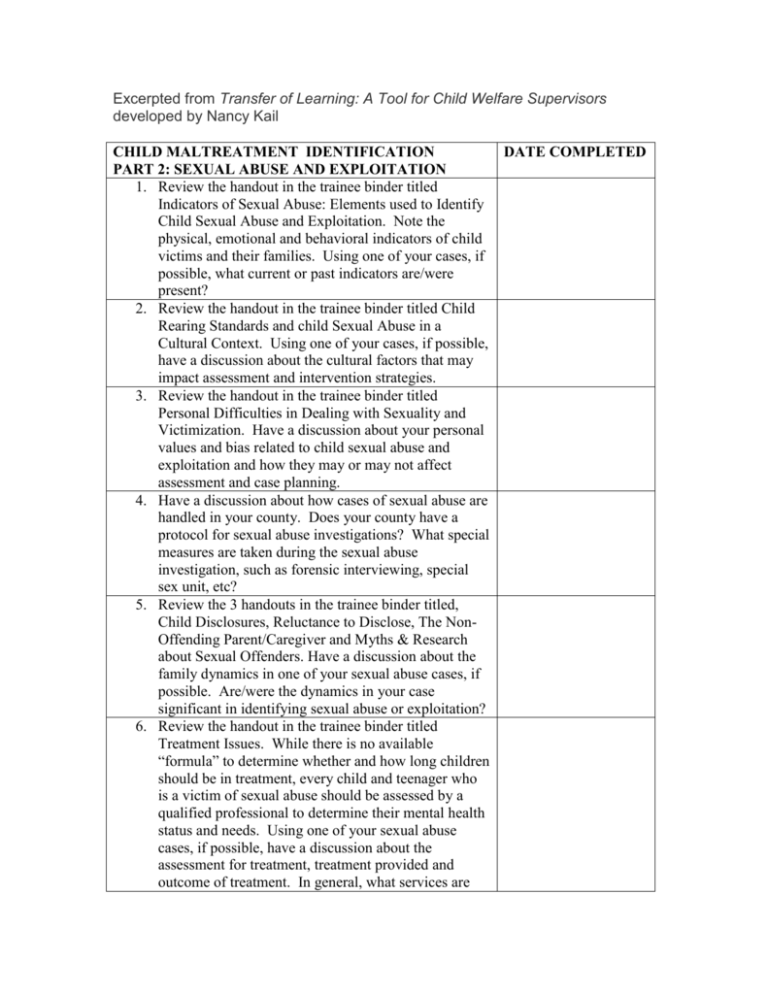

CHILD MALTREATMENT IDENTIFICATION

DATE COMPLETED

PART 2: SEXUAL ABUSE AND EXPLOITATION

1. Review the handout in the trainee binder titled

Indicators of Sexual Abuse: Elements used to Identify

Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation. Note the

physical, emotional and behavioral indicators of child

victims and their families. Using one of your cases, if

possible, what current or past indicators are/were

present?

2. Review the handout in the trainee binder titled Child

Rearing Standards and child Sexual Abuse in a

Cultural Context. Using one of your cases, if possible,

have a discussion about the cultural factors that may

impact assessment and intervention strategies.

3. Review the handout in the trainee binder titled

Personal Difficulties in Dealing with Sexuality and

Victimization. Have a discussion about your personal

values and bias related to child sexual abuse and

exploitation and how they may or may not affect

assessment and case planning.

4. Have a discussion about how cases of sexual abuse are

handled in your county. Does your county have a

protocol for sexual abuse investigations? What special

measures are taken during the sexual abuse

investigation, such as forensic interviewing, special

sex unit, etc?

5. Review the 3 handouts in the trainee binder titled,

Child Disclosures, Reluctance to Disclose, The NonOffending Parent/Caregiver and Myths & Research

about Sexual Offenders. Have a discussion about the

family dynamics in one of your sexual abuse cases, if

possible. Are/were the dynamics in your case

significant in identifying sexual abuse or exploitation?

6. Review the handout in the trainee binder titled

Treatment Issues. While there is no available

“formula” to determine whether and how long children

should be in treatment, every child and teenager who

is a victim of sexual abuse should be assessed by a

qualified professional to determine their mental health

status and needs. Using one of your sexual abuse

cases, if possible, have a discussion about the

assessment for treatment, treatment provided and

outcome of treatment. In general, what services are

available, in your county, for sexual abuse victims and

their families?

Trainee Content for Day 1, Segment 6

Indicators of Sexual Abuse:

Elements Used to Identify Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation

This section of the curriculum outlines the elements that are examined to determine

whether sexual abuse has occurred. Many of these elements are often referred to as

indicators of child sexual abuse. The elements are divided into four broad categories:

Reporting (including aspects of the allegation and disclosure);

Physical (including medical indicators);

Behavioral (including emotional indicators for the victim); and

Familial (including family and caretaker dynamics).

Reporting Elements

Several elements must be considered that relate to the reporting of the allegation,

including the circumstances of the disclosure of the sexual abuse by the child or another

person.

1. Credibility of the report (and the reporter)

This element includes looking at a report and who reported it, and determining whether

the report is credible.

Social workers should consider the clarity of the report, including whether the

reporter had direct knowledge of the incident, or whether they are able to provide

specific information as to time, place, etc.

When evaluating a report of sexual abuse, the social worker should consider if there

is some advantage to an involved party related to the sexual abuse allegation. This is

most common in cases when sexual abuse allegations arise in the context of a divorce

and custody dispute.

Consider the reporter’s motive for reporting. For example, a school social worker or

teacher might be perceived as credible while a parent engaged in a custody battle

might be much less so. More credible reporters may include medical personnel,

school staff, and mental health professionals.

The alleged perpetrator or the non-offending parent may, individually or together,

attempt to undermine the credibility of the reporter or the credibility of the child’s

report. For example, they may attack the reporter and say the reporter has a vendetta

against the perpetrator.

2. Type and credibility of the child’s disclosure

The circumstances and type of the disclosure must be considered when attempting to

determine if sexual abuse occurred.

A direct, unprompted verbal disclosure by the child is most highly correlated with

sexual abuse. Such disclosures may happen inadvertently or intentionally.

The specificity of the disclosure is important. Disclosures with specific details about

where they were, what they were wearing, and what exactly the alleged perpetrator

did may be more reliable than vague disclosures that lack detail.

Children will sometimes recant a disclosure of sexual abuse once they have made it,

depending on the response of their family or the person to whom they made the

disclosure.

Often, children’s disclosures are tentative. They “hint” at what is going on (“I don’t

want to go home…”; “I don’t like my Dad anymore”; or “I know someone who….”)

to test the waters of how non-offending parents and other adults might respond.

Disclosures made to a trained interviewer in a forensic setting (such as a multidisciplinary interviewing center) are more reliable, since the interviewer is

specifically trained to ask questions that do not influence the disclosure.

It is also possible for children’s statements to be misunderstood because of

bizarre, fantasy-like, or implausible aspects of the disclosure. 1 Any disclosure of

sexual abuse, no matter how tentative or bizarre, should be evaluated seriously by

CPS and law enforcement.

More information on child disclosures will be covered in Segment 8.

CSA and custody dispute: CPS workers are frequently called upon to evaluate CSA

allegations in the context of custody and visitation disputes. Many investigators in CPS

and law enforcement question the credibility of allegations made under these

circumstances.

Reports of sexual abuse do increase during those times, for any number of reasons—

including the fact that the discovery of the abuse itself may have prompted the divorce.

Social workers should evaluate the validity of sexual abuse allegations that occur during

child custody disputes—by examining the particular information related to the case.

It is much more likely that children will deny true abuse than make false

accusations. 2

3. Corroboration of disclosure/report

1

For more information, see Everson, Mark (1997). Understanding bizarre, improbable, and fantastic

elements in children’s accounts of abuse, Child Maltreatment, Vol. 2, No. 2.

2

For more information, see Faller, 1991.

Corroboration is defined as the confirmation that some fact or statement is true through

the use of some kind of observable evidence. Since there is often no direct evidence of

sexual abuse, corroborating evidence often helps to confirm whether sexual abuse

occurred. Corroborating evidence should be observable.

Since sexual abuse is often shrouded in secrecy and coercion, the only two witnesses to

the event are generally the perpetrator and the victim. In some cases, however, someone

witnesses sexual abuse, and this should be considered.

The statements and observations of other parties about the allegation may be

considered. This might include the statement of teachers, non-custodial parents, and

others who are able to verify some of the facts related to the report.

The statement of the alleged perpetrator may be considered. If law enforcement has

obtained a confession or some other incriminating (or vindicating) statement from the

alleged perpetrator, this should be considered. Remember that interviews with

alleged perpetrators should be coordinated with law enforcement whenever possible.

Other corroborating evidence, such as copies of letters/emails/text messages, pictures,

or videotapes should be considered.

Corroborating evidence may support details about the case. For example, if the child

talks about it happening in a bed with Superman sheets, and those sheets are indeed,

in the closet, then that would be considered corroborating evidence. Other examples

of corroborating evidence include witness statements, medical exams, pictures of

bruises, and witness statements (e.g., a neighbor provides a statement that the stepdad

babysat the girls every Saturday morning).

Corroboration could include verification/observation of injuries to the body (aside

from the genitalia) that were sustained during the sexual abuse. These might include

bruises or injuries sustained trying to restrain the child, for example (e.g., finger tip

bruises on arms). Injuries to the genitals are covered in Elements 6 and 7.

Corroboration of other facts related to the report should also be considered, such as

whether the alleged perpetrator and victim were together at the time of the alleged

incident.

4. Statements about prior unreported sexual abuse

Of these children by any caregivers, or

By these caregivers toward any children

For families that both are and are not involved with CWS, there may be a history of

unreported sexual abuse of the children or a history of unreported maltreatment by the

parents/caregivers of any children (in or out of the household). CWS social workers

should assess for possible unreported maltreatment history, not only to complete a

comprehensive picture in the identification process of child maltreatment, but also

because:

these are important factors in the assessment of safety, risk, and protective capacity,

these are important pieces of information to consider in the development of case

planning services for children, youth, and families involved with CWS, and

these factors may affect the eventual placement of the child(ren) with extended

family, friends, or non-relative foster caregivers.

Prior suspicions or allegations of sexual abuse may be more likely to go unreported, since

allegations of sexual abuse are considered taboo to discuss. This is also culturally

mediated, in that a family may have handled the prior report of sexual abuse without

involving the child welfare system (such as having the perpetrator attend church services,

sending the child or perpetrator away for a period of time, etc.).

Note: For this element, consider statements about sexual abuse that are not related to the

current report. The current report or allegation could be a longstanding abusive situation,

and this would not be prior abuse. Examples of prior unreported abuse would include

sexual abuse of the same child by another perpetrator, or sexual abuse of another child

under the care of the caregivers.

5. History of CWS Involvement

With these children, and/or

With these caregivers

Because of the family dynamics involved in sexual abuse, there may be sexual abuse in

the family that involves another family member or a member of the extended family who

has access to the children. In addition, prior reports of abuse and neglect in the family

may indicate lack of supervision, which would create an opportunity for a sexual

perpetrator to befriend or coerce a child victim.

Prior CWS involvement indicates there is a higher risk of maltreatment. Review prior

records carefully to see if there is a pattern and to gain a thorough understanding of

the case history. In some cases, multiple allegations of sexual abuse have been made

on a family, or against a particular member of the family. A family with significant

resources to pay for legal services may be able to successfully have the cases closed

by the Juvenile Court, but multiple prior allegations may indicate that the alleged

perpetrator or non-offending parent are able to successfully cover up allegations of

abuse. CWS social workers should make sure to obtain as much information as

possible about prior allegations of sexual abuse, either in their county or another

jurisdiction.

Prior Juvenile Court involvement indicates increased risk of maltreatment. This

indicates there were family issues and problems that required a high level of

intervention. It indicates a history of maltreatment to the child or a sibling of the

child.

Children freed for adoption/never reunified indicates high risk. These include

children who were made dependents of the court for some type of maltreatment; the

parents were offered services for their return and did not substantially comply with

their reunification plan. Based on the history, this indicates a risk for other children

living with those parents.

If parents have other children who are not living with them, this may be a risk factor.

Make sure to inquire if parents have had any other children who do not live with them

now.

If parents have deceased children, make sure to include this information as well.

Inquire about and note the date, cause, and location of death. This can also be a risk

indicator.

Physical Elements

When a child has been physically involved in sexual activity, there may be physical

indicators or injuries that can be validated through a medical examination by medical

personnel trained in the identification of the signs of child sexual abuse. This is not true

in all cases, however; some children who have been sexually abused will have no

physical indicators of the abuse, even when a comprehensive forensic examination is

conducted within 72 hours of the alleged abuse.

6. Presence of illness or injury(ies)

This element refers to current illness or injury as a result of sexual abuse that can be

documented. These might include (adapted from Rycus & Hughes, 1998, p. 163):

Physical injury to the genitals or another part of the body related to the circumstances

of the abuse (for example, marks or indicators of restraint)

The presence of sexually transmitted diseases

Suspicious stains, blood, or semen on the child’s underwear, clothing, or body

Vaginal discharge, bleeding

Genital pruritis (itching)

Presence of a vaginal foreign body

Recurrent bladder or urinary tract infections

Early, unexplained pregnancy, particularly in a child whose history and behaviors

would not suggest sexual activity with peers

Encopresis, constipation secondary to anal discomfort

These illnesses may or may not be discovered as part of a forensic medical examination

completed as part of the investigation and assessment of the allegations.

Note: Children who have been sexually abused often come to the attention of medical

professionals with general medical symptoms or somatic complaints, such as stomach

aches, insomnia, etc. These are considered under Element 15.

7. Report of past illness or injury (ies)

This element refers to past injuries or illnesses, as above, which were not reported or

recorded as sexual abuse at the time of occurrence. Examples of this might be a report by

a parent or other caregiver that they had noticed soreness or redness in the vaginal area

after previous contact with the alleged perpetrator, but had assumed that it was due to a

problem with hygiene. Conversely, a caregiver might report that the child has a chronic

rash in the genital area, and that they have been working with the pediatrician to address

the problem.

Whenever possible, the social worker should have the parent sign a release of information

form so that they can verify the information provided with the child’s medical provider.

8. Explanation of illness or injury (ies)

This element refers to the explanation given to the injury or illness. It is highly unlikely

that a young child would develop an STD accidentally, and injuries to the genital area are

fairly rare. Medical or nursing personnel with experience in evaluating sexual abuse

should be consulted when evaluating this element.

When attempting to determine whether sexual abuse has occurred, it is vital to verify all

the claims and explanations for illnesses and injuries. The information that you receive

from the parent may differ from the physician’s assessment, and this should be noted.

Information from a doctor or other health professional should also be assessed critically,

particularly if the health professional is not specially trained in sexual abuse.

Some family physicians may not consider that sexual abuse is a possible cause of a

given medical condition, especially if they have a longstanding relationship with the

family.

Conversely, some medical professionals may become convinced that sexual abuse has

occurred, when an alternative hypothesis appears more likely.

9. Developmental abilities of the alleged victim

The developmental ability of the victim may make them more vulnerable to coercion by

the alleged perpetrator, or make them more easily manipulated or threatened by the

perpetrator. Developmental abilities can refer to a child’s growth, motor skills (gross and

fine), cognitive development, verbal skills, and social/emotional development.

Vulnerability of the child should be considered. Of course, younger children have less

developmental abilities. Children who have impaired or reduced developmental abilities,

particularly in comparison to their peers, may have more vulnerability to abuse. This is

particularly relevant for children with delayed language skills. They may also be more

dependent upon their caregivers, thus increasing the power differential.

Children with impaired or reduced developmental ability have an increased risk of being

maltreated. Child maltreatment may affect development which in turn can precipitate

further abuse (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001).

10. Developmental abilities of alleged perpetrator

Note: This element only applies when the alleged perpetrator is also a child.

Sexual behavior should be considered in light of the developmental level, rather than just

the age. In cases of sibling abuse, or sexual activity between an older child and a

younger child, the developmental abilities of the alleged perpetrator should be

considered. The impact on the victim should be the overriding concern when identifying

sexual abuse.

11. Medical assessment findings

Medical Evaluation of Sexual Abuse

An important part of the sexual abuse investigation is the forensic medical exam. In

California, law enforcement officers often authorize sexual abuse examinations as part of

their investigation. However, CPS workers may also authorize3 the exam and may

choose to do so even if law enforcement has declined, because the medical exam has both

physical and psychological benefits (see below). CPS workers should be familiar with

what the usual protocol is in their county for obtaining an exam. Many counties have

specialized, child-friendly pediatric sexual assault clinics as part of their county’s

Multidisciplinary Interview Center/Child Advocacy Center. Other counties perform both

acute and non-acute (see below) exams at hospital emergency rooms.

Types of Medical Evaluations

There are two types of sexual abuse examinations: acute evidentiary (immediate, sameday) and non-acute (as soon as possible after disclosure).

Acute examinations include:

Collection and preservation evidence (semen, saliva, hair, fibers on clothes, etc.)

following a recent sexual abuse/assault episode (usually within past 72 hours,

sometimes longer);

Evaluation, documentation, and treatment of any injuries;

Evaluation for and prophylactic treatment for STDs and pregnancy; and

Provision of crisis intervention services.

Most child abuse forensic examinations are of a non-acute nature (over 72 hours since

last incident of abuse/assault) because of the dynamics of delayed disclosure (discussed

above).

Non-acute forensic examinations include:

Evaluation, documentation and treatment of any injuries;

Evaluation and documentation of old or healing injuries/trauma;

Provision of (post-disclosure) crisis intervention;

Assurance of the physical and psychological well-being of the child.

When Should Children Be Referred for a Forensic Medical Examination?

There is a distinction between “authorization” and “consent.” Authorization refers to

the legal authority that requests that the exam be completed at public expense. Consent

refers to permission to perform the exam and release the results to those with legal

authority to obtain the results. Children over 12 must consent to the exam themselves,

but the exam should not be performed by force even on younger children. Refer to

Family Code 6927 and 6928 for further information on consent issues with minors.

3

In all cases in which the most recent episode of abuse/assault occurred within the

last 72 hours (these children should be taken to an emergency room or 24-hour

evidentiary clinic). Note: Due to advances in forensics/evidence gathering

techniques, some jurisdictions perform forensic medical examinations after longer

intervals. When an assault has been disclosed, check with the forensic medical

practitioner to see if an immediate examination is warranted.

When there is a disclosure of penetration, regardless of time elapsed.

When there is evidence by history of pain, trauma, or infection, regardless of time

elapsed.

When the child has physical complaints related to the abuse.

If the disclosure is incomplete or the details are unclear and this might be clarified by

an examination.

When the child or family has questions that would best be answered by an expert

medical practitioner.

When the child would benefit from reassurance that he/she is “okay.”

In summary, the medical evaluation is a very useful tool for CPS workers. Children

benefit both physically and psychologically from the opportunity to meet with a medical

specialist to talk about their bodies. Medical examinations can also yield forensic

evidence that is admissible in both dependency and criminal courts, or medical examiners

can explain why the absence of findings may be consistent with a child’s statements. CPS

workers are encouraged to develop relationships with the medical evaluators in their

counties and to ask for explanations of the findings and the forms/documentation

associated with the sexual abuse medical exam.

Behavioral Elements

12. History of sexually abusive behavior by someone in the home or with access to

the child

This is perhaps the most important indicator of possible sexual abuse, aside from a clear

verbal disclosure by the child. Adults with a history of sexual interest in children are

very likely to re-offend, particularly without intensive treatment. The CWS social worker

should ascertain whether anyone who had access to the children has a history of sexual

behavior with children, either reported or unreported. The non-offending parent may or

may not have knowledge of the history of the perpetrator, and may or may not believe the

allegation (see Familial Elements).

Note: For this element, consider behaviors that are not related to the current report. The

current report or allegation could be a longstanding abusive situation, and this element

would not be relevant. This element would apply to sexually abusive behavior toward

other children, either within or outside the home.

13. Developmentally or socially inappropriate sexual knowledge and/or sexual

behavior

Non-abused children and sexually abused children may exhibit common sexual behaviors

(see the Toni Cavanagh Johnson charts earlier in this curriculum). This may make it

difficult to distinguish between sexual behaviors that appear to be the result of sexual

abuse and those that are not.

Sexual behaviors that are common for non-abused children include self-stimulating

behaviors, exhibitionism, and behaviors related to personal boundaries. Less frequently

seen behaviors in non-abused children are more intrusive, such as putting the mouth on

sex parts or putting objects into the vagina or rectum. Behavior that suggests a child’s

explicit or inappropriate knowledge of adult sexual behavior and compulsive

masturbation warrant further investigation.

The CWS social worker should pay special attention to the onset of a shift in behavior(s)

away from the child’s baseline, and whether this coincides with the onset of the abuse

that was alleged, or with the alleged perpetrator’s access to the child. An example of

such a shift in behavior is when a child’s clothing or style of dress changes from one style

to another (either more provocative style of dress or very covered up).

14. Self-protective behavior by the alleged victim

This element includes physical and behavioral methods that the victim uses to protect

themselves from the sexual abuse. The child may attempt to prevent the abuse from

happening long before the abuse is disclosed.

Examples of protective behavior might include:

Attempts to make themselves as unappealing as possible sexually (e.g.,weight gain,

poor hygiene, etc.)

Wearing layers of clothing to make body contact more difficult

Refusal to visit the alleged perpetrator after the onset of the abuse, or attempts to

avoid unsupervised contact with the alleged perpetrator

Temper tantrums when returning to the care of the alleged perpetrator

15. Indicators of emotional distress by alleged victim

Children who have been sexually abused may display a variety of indicators of emotional

distress. The presence of these indicators of distress does not in and of itself indicate that

a child has experienced sexual abuse, however. All of them are also signs of trauma or

distress that could be caused by other forms of abuse, or other sources of stress. The

indicators below are broadly grouped in terms of trauma-related indicators, depressionrelated indicators, anxiety-related indicators, and other indicators.

When evaluating these indicators, the CWS social worker should pay special attention to

the onset of the behaviors, and whether this coincides with the onset of the abuse that was

alleged, or with the alleged perpetrator’s access to the child.

Trauma-related indicators:

Physiological reactivity/hyperarousal (hypervigilance, panic, and startle responses,

etc.)

Retelling and replaying of trauma and post-traumatic play

Intrusive, unwanted images and thoughts and activities intended to reduce or dispel

them

Sleeping disorders with fear of the dark and nightmares

Dissociative behaviors (forgetting the abuse, placing self in dangerous situations

related to the abuse, inability to concentrate, etc.)

Cutting behaviors

Anxiety-related indicators

Obsessive cleanliness

Self-mutilating or self-stimulating behaviors

Changed eating habits (anorexia, overeating, avoiding certain foods)

Depression-related indicators

Lack of interest in participating in normal physical activities, loss of pleasure in

enjoyable activities

Social withdrawal and the inability to form or to maintain meaningful peer relations

Profound grief in response to losses of innocence, childhood, and trust in oneself,

trust in adults

Suicide attempts

Low self-esteem, poor body image, negative self-perception, distorted sense of one’s

own body

Other indicators

Personality changes

Temper tantrums

Running away from home

Premature participation in sexual relationships

Prostitution

Aggressive behaviors or irritability

Regressive behaviors in young children (thumb sucking or bedwetting)

Poor school attendance and performance

Somatic complaints

Accident proneness and recklessness

Excessive piercings

Dressing down, dressing in thick layers, padding or taping down genitals

Perfect child/extremely high achiever/overly controlled/rigid

Heightened sexualized behavior

Indiscriminate sex

16. Coaching or grooming behaviors

The CWS social worker should try to determine if the perpetrator groomed or prepared

the child for the abuse, by providing special attention to the child, or by escalating the

type and intensity of sexual contact.

Gathering and assessing this information can be difficult, since grooming or coaching

behaviors are often subtle, and difficult to distinguish from normal expressions of care

and affection by adults. Sexual perpetrators often provide the same kind of attention that

is appropriate for a parent or grandparent to provide to children.

Sexually abusive adults often groom or initiate children by disguising their motives

through the use of games, secrets, toileting/bathing, and tickling and/or wrestling.

Offenders often “teach,” “help,” and “mentor” older children. They may treat children to

special gifts, special time, and special favors. They may use kid games (videogames,

Gameboy) and interests (sports, motorcycle riding) to connect with them and/or to use for

coercive purposes. They may also expose children to sexual talk and pornographic

movies to desensitize them to sexuality and have frequent physical contact (tickling,

wrestling, hugging, touching) to desensitize children to touch.

Familial Elements

17. Isolation of the child

The more isolated a child is socially and emotionally, the fewer opportunities they will

have to disclose abuse. Moreover, if they feel emotionally isolated, they may be less

compelled to disclose. A child who is socially or emotionally withdrawn may also

present a “safe target” for a perpetrator. But this isolation may also be a reaction to the

abuse.

This element also includes active attempts by the alleged perpetrator to keep the child

isolated from outside social contacts or influences that might cause them to disclose the

abuse. This might include physically isolating the child from outside contacts such as

social groups, school, church, etc. The child may also be isolated in the home, or even

self-isolating from his or her normal activities. The perpetrator might also engage in

isolating behaviors and have, for example, little contact with adult peers. Isolation

encompasses both the physical aspect of isolation as well as emotional separateness.

18. Coercion/threats made to the child to prevent disclosure

The perpetrator will sometimes threaten harm to the child if they disclose the abuse to

their parent or another adult. Threats might include, but are not limited to:

Threats of physical harm to the child or the child’s family

Threats to a treasured object of the child, such as a family pet

Threats that the family will dissolve, or that the child will never see the alleged

perpetrator again (especially in cases of incest)

Threats that appear fantastical to an adult, but may be believable by the child, such as

threats that the child will “go to hell” or that the perpetrator will use some sort of

supernatural powers to harm the child

Threats regarding the safety of the family

Promises of gifts

Other coercive behaviors may also be present, such as bribes or special prizes given to

the child by the perpetrator in exchange for keeping the “secret” of the abuse.

A non-offending parent who does not believe that the abuse occurred may threaten the

child as well.

The CWS social worker should pay special attention to coercion and threats when

children appear extremely anxious and fearful about the disclosure, or make frantic

attempts to recant their previous disclosure. A forensic interview may be able to sort out

whether threats or coercion were evident.

19. Current caregiver’s substance abuse

A significant number of children in this country are being raised by parents with

addictions. With more than 1 million children confirmed each year as victims of child

abuse and neglect by state Child Protective Service agencies, state welfare records have

indicated that substance abuse is one of the top two problems exhibited by families in

81% of the reported cases4. Cases of sexual abuse may also involve substance abuse by

the parent or guardian.

Children may be poorly supervised by parents who are under the influence, out

looking for drugs, passed out, and coming down off of drugs, or who leave children

unattended when under the influence. The inebriated or high parent may leave

children in the care of inappropriate caregivers who may subject them to physical

abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect. Parents who are under the influence have

compromised judgment and compromised ability to provide appropriate nurturing,

care, and supervision to children.

Loss of impulse control by parents/caregivers under the influence can lead to violence

and abuse, including sexual abuse. There may be an overlap with domestic violence

and substance abuse.

People may lie/minimize while under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

20. Opportunity for the abuse to occur

When identifying whether sexual abuse occurred, the CWS social worker must consider

the opportunity that the alleged perpetrator had to abuse the child. This includes the

home environment, and the capacity of the non-offending parent to perceive that the

abuse may be occurring and protect the child if they suspect that it is.

The non-offending parent may have a great deal of difficulty recognizing the possibility

of sexual abuse, even when it seems obvious to an outsider. The alleged perpetrator may

hold great emotional power over the caregiver, with the result that the caregiver might

not be able to see sexual abuse as a possibility. Examples of this might include when the

alleged perpetrator has very high status in family’s community, such as a church elder or

a community leader.

There may be lack of boundaries in the home, such as no set sleeping locations or the

child/ren not having their own bed/space or privacy.

4

National Association for Children of Alcoholics. (1998). Children of alcoholics: Important facts.

Rockville, MD.

The non-offending caregiver may also have to work long hours, and may not have the

resources to provide licensed child care for supervision of the child.

Note: This element is often more important in determining that sexual abuse did NOT

occur, i.e., in cases where there was no possibility of contact between the alleged

perpetrator and the alleged victim. This is because most children are alone with other

children or adults at least part of the time. This does not mean that sexual abuse may

occur, unless there are other circumstances that make the opportunity particularly

striking. These might include, for example, a parent who refuses to supervise a child or

children even in a situation that might be sexualized.

Trainee Content for Day 1, Segment 5

Child Rearing Standards and Child Sexual Abuse in a Cultural Context

Sexual Behaviors in a Cultural Context

Before the worker can identify any behavior as abnormal, it is important to become

familiar with the normal sexual development, related behaviors, interactions, and feelings

of the growing child. It is important to remember that no child will follow these

developmental stages exactly. Deviations in behavior do not necessarily indicate a serious

problem or sexual abuse in particular, but they should be assessed in the context of the

history, physical findings, and the child’s family environment (Hillman & Solek-Tefft,

1988).

Child Rearing Standards in a Cultural Context (refer back to CMI-1)

The definition of child abuse has changed over time and varies according to the values

and beliefs of the majority culture. Thus child maltreatment can be viewed in a cultural

context as a reflection of the time and area in which we live. Child rearing standards in

general also may be viewed in a cultural context. What defines good parenting today

differs significantly from times past. What is considered optimal parenting also varies by

the culture, time, and place in which one lives.

Child Sexual Abuse in a Cultural Context

In non-clinical studies, Caucasian and African-American women have similar rates of

abuse with Asian rates slightly lower. Latinas are at increased risk for incest. The reasons

for these cultural differences are not clear (Fontes, 2005).

Cultural Aspects of Shame in Child Sexual Abuse:

Responsibility for the abuse

The assignment of responsibility for the abuse can vary widely across cultures. In

many traditional cultures, sexual relations are viewed as a fundamental struggle:

something females should try to avoid and males of all ages should try to obtain.

Where sexual acts have occurred outside marriage, the girl or woman is assumed to

have made herself accessible and is often held responsible, even when there is a

difference in age or power between the people involved. A Peruvian woman

described how her brother had been found to be having sexual relations with his 9year-old stepdaughter, and how the girl was banished to a convent. “It wasn’t his

fault!” she insisted. “The girl was right there with him and was very pretty. She wore

short dresses. She sat on his lap. She asked him to tuck her in at night. Her mother

was away for a month. He couldn’t help himself!” (Hillman & Solek-Tefft, 1988).

It is important for workers to understand cultural norms around the assignment of

blame and responsibility. At the same time, professionals need to help their clients

place responsibility for past incidents on the shoulders of the perpetrator, and ensure

that different family members take responsibility for future protection of the child.

Failure to protect

Nonoffending family members are often ashamed of having failed to protect a child

from sexual abuse-thereby having proved themselves inadequate in a key task of their

cultural roles as mothers, fathers, older brothers, etc. A man whose child has been

victimized may feel like a failure as a man; his sense of failure could drive him to

physically attack the perpetrator to recover his feelings of dignity and self-worth.

Professionals need to show fathers and other concerned adults ways in which they can

actively and positively participate in the child victim’s recovery and protect other

children (Pearce & Pezzot-Pearce, 1997).

Fate

People with a culturally fatalistic view, believing that forces outside or beyond an

individual determine the life course, will often respond quite passively to the

discovery of sexual abuse. This world view is unlikely to be changed.

The worker can ask each person involved, “How do you explain why the abuse

happened?” in an effort to determine if they see fate as the reason for the abuse. A

worker can then follow up with a statement such as:

o “Thank you for letting me know how you explain what happened. I’d like to

suggest a couple of other ideas, so you can know how I think about it. I expect

that both perspectives contain some truth. ____________ chose to abuse your

child because______________ has sexual feelings toward children, and found a

way to be alone with your child and act on those feelings. We can work together

to help your child and family recover from this, and to make sure nothing like this

happens again. I encourage you to continue to do all the things you are doing to

help you to cope [e.g. praying]. I have ideas about other things that could be

helpful to you and your child too, and have been helpful to other people in your

situation” (Fontes, 2005, pp.143-145).

Damaged goods

There is a sense of being “soiled” or “spoiled” and the child may come to believe they

are “dirty” as a result of the abuse. If the knowledge of the sexual abuse were to

become known in their community, the family and child might be ostracized and

considered unworthy. The girl victim might also lose her potential value as a future

wife and daughter-in-law, an important part of a grown woman’s identity in many

cultures around the world.

Virginity

Many cultures control women’s sexuality by expecting girls to maintain their

virginity until marriage. This expectation includes traditional families from many

parts of Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas. In some traditional

cultures, a girl who has engaged in any kind of sexual activity, even forced, may well

be perceived as losing her virginity, and thereby be considered either not suitable for

marriage or of lesser value as a bride.

“In many places the absence of virginity may mean that a young girl loses her chance

for marriage. If the situation is known, she loses her prestige within the family [just]

as the family loses it in their close neighborhood…Sexual abusers seem to pay

attention to this issue, and some girls are threatened with “losing their hymen” which

explains [the elevated presence of] nonpenetrating sexual abuse. On the other hand,

the first reaction of the nonoffending parent and other relatives is to take the child or

young girl for an examination of her virginity, when they find out about the abuse. If

the hymen is left intact, the sexual abuse cannot be proved, and this makes the denial

easier for the family. Professionals, therefore, emphasize that fact that the presence of

the hymen does not preclude sexual abuse” (Yuksel, 2000).

Predictions of a shameful future- promiscuity, homosexuality, and sexual offending

People from many cultures believe that girls who have suffered sexual abuse are

likely to become promiscuous and boys who have been sexually abused by men are

likely to become either homosexuals or sexual offenders. There is no indication that

sexual abuse will influence a boy’s later sexual orientation (Arey, 1995). Boys who

have been sexually abused appear to engage in more sexual behaviors, such as

masturbation, sexual play, and sexual aggression with younger children, than boys

who have not been sexually abused (Friedrich, Grambsch, Damon, Koverola, Hewitt,

Lang, & Wolfe, 1992).

Re-victimization

In some cultures, when a girl is known to have been sexually abused, she has lost the

special protective aura of virginity and is considered to be “fair game” for other men

to try to seduce or assault. Russell (1986) suggests that knowledge of prior

victimization may disinhibit some perpetrator’s abusive tendencies toward these girls.

Grauerholz (2000) describes a variety of reasons why girls and women may be more

likely to suffer further experiences of sexual assault following sexual abuse in

childhood: continued exposure to the factors that put her at risk in the first place,

lessened ability to detect danger, and the use of substances that inhibit her ability to

avoid dangerous situations or to escape from them.

Layers of shame

There are factors which the individual might already feel a sense of shame about

because they are not congruent with what is valued by the majority culture, such as

skin color, hair texture, eye shape, or social status. The sexual abuse and its

consequences magnify these factors (Fontes, 2005).

Gender and Role Differentiation Issues Influencing Child Sexual Abuse

Double Standard between Male and Female Children:

In almost every society, expectations of and for male and female children are different.

This difference is frequently reflected in the expression of sexual behaviors. When we

talk about the sexual victimization of children, if you have a 12 year old girl who is

molested by a 25 year old male, no one has a problem in seeing the girl as a victim of

sexual abuse or exploitation. In general, child protection and law enforcement systems

will move to protect the child and hold the perpetrator accountable for the violation of

criminal laws. If the child is a 12 year old boy and the perpetrator is a 25 year old

woman, there is much more ambivalence in viewing the boy as a victim, and in fact,

many may see him as “lucky”. Within some cultures this may be seen as a desired part of

his development as a man. The protection and enforcement systems may be slower to act

to protect, the family may be less supportive of such intervention, and the child not seen

in need of therapeutic services.

However, if the 12 year old boy has been molested by a 25 year old male, the paradigm

shifts and the child is now without question, the victim, and the adult responsible, an

offender. The protective systems come in rapidly and act to protect, the family feels a bad

thing has happened to their son, and the belief is that without therapeutic intervention the

child may suffer long term, potentially severe, consequences. There is also the additional

concern he will become either a perpetrator himself, or, within some cultures, a

homosexual (Fontes, 2005). The scenario of the 12 year old female being molested by a

25 year old female is rarely considered.

The double standard also is reflected in the behaviors considered “normal” or appropriate

for a child or adolescent within that culture. As noted in earlier classes, culture is

evolving, and the norms, including sexual norms, change over time. In general, males

have more freedom and are allowed a wider expression of sexual behaviors than females,

with fewer repercussions or sanctions when they violate cultural or community norms.

The value of a boy or man’s masculinity may hinge on the number of his conquests, and

the value of a girl or woman’s femininity may hinge on her chastity (Fontes, 2005). It

may be difficult for families to assign responsibility appropriately in cases of brothersister incest, particularly in cultures that value boys more highly than girls. Parents

frequently minimize or deny the significance of brother-sister incest, or they blame the

girl (Fontes, 2005).

Sexual Orientation – Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgendered & Questioning Youth

What is allowed in terms of expression or exploration of sexual identity also varies

between cultures, ages, and genders. “Expectations for gender roles and heterosexual

activity are communicated overtly and covertly and are the ways and means through

which girls and boys learn the values, beliefs, and customs of conventional masculinity

and femininity” (Ungar, 2005, p. 266). Same sex experimentation may be more expected

and/or excused among younger children or one gender. Because homophobia and

heterosexism continue to be largely unchallenged in contemporary society, lesbian, gay,

bisexual, transgendered, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth frequently face overt

discrimination without intervention from others. The Gay, Lesbian, and Straight

Education Network’s survey of LGBTQ students across the United States reported that

83% had been verbally harassed and 42% had been physically harassed in school, with

84% of high school students hearing the words faggot or dyke in the classroom frequently

or often (Ungar, 2005). This peer isolation, added to family lack of acceptance may

increase the child’s search for love and acceptance in unsafe ways with individuals more

predisposed to abuse or exploiting them.

Trainee Content for Day 1, Segment 2

Personal Difficulties in Dealing with Sexuality & Victimization

Emotional reactions to child sexual abuse is normal and to be expected. However, it is

important to recognize our emotional reactions to prevent them from impairing our

professional judgment or performance of our duties as child welfare workers. Despite

education and training, which specifies how to perform our professional roles, it is

normal for each of us to have personal reactions to our work. Child sexual abuse probably

arouses more personal reactions than many of the problems we encounter. Although these

may become less intense over time, they do not disappear. Initially, the enormity of

sexual abuse is likely to engender one of two opposing responses—disbelief or belief

accompanied by an intense desire for retribution.

Gender

The gender of the professional is likely to influence reactions to cases of child sexual

abuse. Both male and female professionals have empathy for victims. However, it is

possible that gender identification causes each to be more sensitive when the victim is of

his or her own gender. Professional reactions to sexual abuse may differ by gender

because men and women experience living in society differently.

Life Experiences

Many life experiences can intrude upon professional practice, and working in sexual

abuse can intrude upon a professional’s personal life. Three personal issues that seem

particularly salient are: having been sexually victimized, being a parent, and sexuality.

Sexual Victimization

A professional who has been sexually abused her/himself or who is part of a family in

which there has been sexual abuse must cope with this personal issue as well as with the

other stresses of work associated with working with sexual abuse survivors. Persons who

have sexual victimization in their background bring special sensitivity and experience

that can be of great value in their work. Nevertheless, professionals who have personal

experiences of sexual abuse need to have addressed these in therapy, be especially aware

of countertransference issues, and be alert to the importance of protecting their own

mental health.

Warning signs that the professional’s own victimization is impeding performance can

include:

□ Feeling so overwhelmed by fear, anxiety, disgust, or anger that the victimization

interferes with sound decision making or intervention or evokes the strong desire for

retribution;

□ Experiencing intrusive thoughts or having flashbacks at work;

□

□

□

Recalling previously repressed memories of victimization when involved in cases of

sexual abuse;

Displaying overly punitive responses to the non-offending parent or offender; and/or

Minimizing or not seeing the safety issues involved in a case, or the severity of the

effects on a child.

Being A Parent

The experience of parenthood can affect one’s reaction to a case of sexual abuse, and

working with sexual abuse can influence parenting. Parenthood can make the

professional more appreciative of the risks as well as more appalled at the transgressions

of the parenting role. Parents are confronted with many situations in which the child’s

behavior (e.g. wanting to sleep in bed between the parents) and parenting responsibilities

(the need to assist the child in bathing, toileting, and understanding the differences

between male and female anatomy) can present risks for sexual activity.

Sometimes, professionals who are parents are less willing to label client behaviors as

sexually inappropriate because of their over-identification with the client as a parent. For

example, a professional who is a father may minimize genital contact between an alleged

offender father and his daughter, accepting the explanation that the daughter was being

helped to learn about “wiping herself.”

Conversely, certain biological drives and normative proscriptions inhibit sexual activity

with children for parents. Because of these personal experiences, parents may be more

censorious than non-parents when these boundaries are crossed. Individual families will

have differing norms for what are acceptable personal boundaries or privacy, male and

female roles in parenting behaviors, and acceptable discussions around perceived or real

sexual matters.

In terms of work influencing parenting, a common effect of professional involvement

with sexual abuse cases is for the parent to become quite concerned about the risk of

his/her own children being sexually abused or exploited. Parents may be hypervigilant to

behavioral or physical indicators exhibited by their own children, such as urinary tract

infections, masturbation, enuresis, and sleep disturbances.

Comfort and History with Sexuality

Being familiar and comfortable with all aspects of sexuality is essential in working in the

field of child sexual abuse. For the professional, this means being able to talk freely about

all types of sexual issues.

Professional involvement with cases of sexual abuse very frequently has an impact on

personal sexuality.

Coping with Personal Issues

The best way to prevent personal reactions from undermining the quality of professional

work is to be aware of their existence. Once these reactions are identified, several

methods can be used to help to mitigate them, including:

□

□

□

□

□

Self-talk, in which the professional reminds him/herself of personal biases and

reactions.

Talking about, acknowledging and processing personal reactions and feelings about

cases with a supervisor, mentor, or trusted colleague. (Note: Remember that all case

information is confidential; child welfare workers need to request time with someone

within the agency, such as your supervisor, to discuss any detailed information.)

Using established guidelines and research to guide decision-making.

When possible, using collaborative decision-making with colleagues involved in the

case.

When the above suggestions are not sufficient, talking about, acknowledging and

processing personal reactions and feelings about cases with a counselor or therapist.

Avoiding Burnout

There is no denying that work in the field of sexual abuse is extremely stressful and may

lead to burnout. There are several characteristics of cases that make the work potentially

Trainee Content for Day 1, Segment 8

Child Disclosures, Reluctance to Disclose

Child disclosure of sexual abuse has generated controversy, with great debate in the press

and the academic community about the validity of children’s disclosures. Many studies

have methodological problems, and/or small sample sizes, exacerbating the controversy.

Only recently has a body of research emerged and analyzed that provides some guidance

for child welfare practitioners. Olafson and Lederman (2006) provide perhaps the most

comprehensive analysis and summary of the available research in their article, The State

of Debate About Children’s Disclosure Patterns in Child Sexual Abuse Cases. Their

summary of research findings are excerpted below, with some clarifying definitions

inserted.

Summary of Research Findings on Disclosure of Children Regarding Their Sexual

Abuse

1. Experts agree that a majority of child sexual abuse victims do not disclose their abuse

during childhood.

2. Experts agree that when children do disclose sexual abuse during childhood, it is

often after long delays.

3. Prior disclosure predicts disclosure during formal interviews. Children who have told

someone about the abuse prior to the formal interview are more likely to disclose

during the interview than children who have not. Children who have not previously

disclosed and who have come to the attention of the authorities because of medical

evidence, videotapes, and other external evidence, are less likely to disclose during

medical or investigative interviews than are previously disclosing children.

4. Gradual or incremental disclosure (where a child may disclose only aspects of an

abusive event during the initial interview) of child sexual abuse occurs in many cases,

so that more than one interview may become necessary.

5. Experts disagree about whether children will disclose sexual abuse when they are

interviewed. However, when both suspicion bias (cases which come to the attention

of the authorities because a child disclosed to someone prior to the formal interview)

and substantiation bias (substantiation was completely independent of the child’s

statements) are factored out of studies, studies with external corroborating evidence

of child sexual abuse show that 42% to 50% of children do not disclose sexual abuse

when asked during formal interviews.

6. School-age children who do disclose are most likely to first tell a caregiver about

what happened to them.

7. Children first abused as adolescents are most likely to disclose than are younger

children, and they are more likely to confide first in another adolescent than to a

caregiver.

8. When children are asked why they did not tell about the sexual abuse, the most

common answer is fear. (We need to ask children in the child interview what they

are afraid will happen if they talk about what happened when…)

9. Further research is needed about recantation rates, which range in various studies

from 4% to 22%.

10. Lack of maternal or paternal support is a strong predictor of children’s denial of

abuse during formal questioning. Abuse by a family member may inhibit

disclosure. Dissociative and post-traumatic symptoms may contribute to nondisclosure. Modesty, embarrassment, and stigmatization may contribute to nondisclosure. Gender, race, and ethnicity affect children’s disclosure patterns.

11. Many unanswered questions about children’s disclosure patterns remain, and further

multivariate research is warranted.

Intentional and Accidental Disclosure

Sgroi (1982) suggested two types of disclosures are encountered—the purposeful and

the accidental. In the former, the child makes the conscious decision to tell of the abuse.

In accidental disclosures, the child has made no overt statement to anyone with the

intention of seeking intervention. The accidental class of disclosure includes such

allegations as those involving sexually explicit play on the part of a preschooler, a

pregnancy in a very young adolescent, a child presenting with a sexually transmitted

disease, the purposeful disclosure of a child victim who names other child victims, or the

observation of the perpetrator-child sexual activity, including the interception of child

pornography.

Where the child has made a purposeful (deliberate) disclosure to an adult, the initial CWS

interview with the child is more likely to yield a more detailed description of the sexually

abusive activity. Even when there is independent evidence or information for the sexual

abuse or exploitation, the child interview might not yield a disclosure if the child has not

cognitively made the decision to tell. Research indicates that multiple interviews are

frequently necessary for a number of children to feel safe or comfortable enough to

disclose.

Trainee Content for Day 1, Segment 8

The Non-Offending Parent/Caregiver

Much research has demonstrated that the non-offending parents’ ability to provide

support following a disclosure of sexual abuse is the most critical factor influencing the

child’s post-disclosure adjustment. Non-offending parents may be viewed on a

continuum. They range from those who, prior to disclosure, have knowledge of the abuse

and do nothing, to those who “sense” something is not right but do nothing, to those who

recognize potentially abusive actions and are proactive in protecting the child. Postdisclosure responses range from those who align with the perpetrator and do not believe

the child to those who immediately believe and take protective action upon hearing a

disclosure.

In her book, The Mother’s Book: How to Survive the Molestation of Your Child (1992),

Carolyn Byerly lists these diverse reactions of non-offending parents after a disclosure of

child sexual abuse:

Numbness

Jealousy

Distance

Sexual inadequacy or rejection

Anger

Religious concerns

Disbelief

Minimizing the seriousness

Denial

Revenge

Shame

Financial and other fears

Invisibility

Hatred

Guilt and self-blame

Repulsion

Hurt and betrayal

A desire to protect him (the alleged

Confusion and doubt

offender)

It is difficult to predict how a particular parent will react. Responses may also reflect

cultural components as well as the non-offending parent’s role in the relationship. Crosscultural marriages and dependency issues may also color both immediate and long-term

responses. Although not all parents experience significant distress following a disclosure

of sexual abuse, many do. Some parents may experience emotional distress and

depression which can be related to loss of income and financial support, changes in

relationships with family and friends, and disruptions in employment and living

situations.

There is growing evidence that when mothers are incapacitated in some way, children are

more vulnerable to abuse. That incapacitation may take a variety of forms. When a

mother is absent from a family due to divorce, death, or sickness, children appear to

suffer more abuse. Mothers may also be psychologically absent because they are

alienated from their children or husband or are suffering from other emotional

disturbances, with similar consequences. Mothers may be unable to protect children

because they themselves are abused and intimidated. Even large power imbalances that

may stem from differences in education may undercut a woman’s ability to be an ally for

her children (Finkelhor, 1984).

When non-offending caregivers first learn about the abuse, their reactions vary

considerably. The majority of mothers believe their child’s allegations, either totally or in

part, and most take some protective action. However, a substantial number did not

believe their children’s allegations and did not take protective action. Some were in the

middle; although ambivalent about the allegations, they took protective action anyway.

Elliot & Carne’s (2001) study examined a history of abuse on non-offending parent

reaction post-disclosure. The study examined four factors to see if parental belief,

support, and protection can be predicted. These factors include: mother’s relationship

with the perpetrator; mother’s own history of childhood abuse; victim’s age; and victim’s

gender. Anecdotal experience suggests that sometimes a parental history of sexual abuse

or victimization may influence whether her ”radar” responds to warning signs that abuse

may be happening. Some mothers who never disclose their own abuse or did not receive

treatment may deny abuse because, by acknowledging it in their children, they must

acknowledge their own history. Most of the above factors yielded inconsistent results,

though some studies indicate that young children are believed more often than older

children and adolescents.

A parent who has introduced the perpetrator to the child or family, such as the single

mother who is dating, may experience denial, guilt, or depression upon hearing the

child’s disclosure of sexual abuse. A mother may go through stages analogous to those

experienced by individuals who are dying, before she comes to believe the child. Denial,

guilt, anxiety, fear of repercussions, or depression may decrease the mother’s ability to

help the child cope with the traumatic experience.

Denial. Denial is a defense mechanism used to avoid psychic trauma or painful

reality. Denial can cause reactions such as: “No, not me, not my child, not my

husband, etc., etc. There must a mistake. My child must be making this up for some

reason.” Instead of immediately being labeled as non-cooperative, it is important for

child welfare workers to distinguish between a normal, initial reaction of disbelief,

which indicates a need for support and service, and chronic denial. As the literature

above notes, even parents who are non-believing or in denial can take protective

measures.

Anger. In the grief cycle, people need to blame someone outside themselves for their

painful situation. Anger may be directed at themselves for not seeing the abuse, at

the child for participating, at CWS and law enforcement for their involvement, at the

“situation,” and, appropriately, at the perpetrator. (Note: Anger may be due to lack

of understanding about the dynamics of sexual abuse. Anger at the child that persists

despite the passage of time or following education and support may be an indicator of

inability to provide support or protection, requiring CWS intervention).

Bargaining. During this phase, the parent tries to regain some emotional stability.

Feelings may alternate between “positive” actions such as reporting, seeking therapy,

kicking out the perpetrator, etc., and “negative” actions such as continuing to seek

alternative explanations, believing the child while allowing the perpetrator to retain

access, thinking they can handle it within the family, etc., and making inconsistent

statements to the child, e.g., “I believe you, but I also can’t believe your uncle is

lying.”

Note: It is very important that child welfare workers make efforts to explore and

understand the motivations behind seemingly negative actions. Sometimes, parents

are doing what they think is best for the child, as in families who would otherwise be

homeless or without any means of financial support or families with domestic

violence and the mother fears that the father may injure or kill her or the children.

Families may also respond in a particular way because of deeply held cultural or

religious beliefs or out of fear of the system response. (See section on cultural

issues.) Understanding these motivations provides windows into important points of

service intervention.

Depression. This is a very painful and uncertain period as the full magnitude of what

has happened sinks in. Depression can be debilitating as the parent feels that her

whole life is defined by the abuse, and is unable to see a future where this will not be

the case. It may be difficult for her to be emotionally supportive of her child because

of her own pain. For non-offending parents with their own history of abuse, this

phase can include a recapitulation of their own abuse experience. (Note: This stage

can be a powerful point of intervention if the parent receives support.)

Resolution. In this final stage, the parent begins to put the pieces of her life back

together, can envision and begin to create a future. It does not mean that she forgets

what has happened, but she can place it in perspective and not have it dominate her

whole life. She can also help the child and siblings with their own healing and

resolution.

In summary, by being aware of the range of responses in terms of belief and

protectiveness, child welfare workers can contribute to better outcomes for children.

While the research on maternal responsiveness is inconclusive, one thing is clear: a

supportive parent is associated with a better outcome for children. For this reason, a

nonjudgmental and empathic approach during the early stages of investigation and

intervention may be more effective than confrontation. Normalizing a parent’s denial or

shock and helping her to understand her response, rather than labeling her as “nonprotective” or “uncooperative,” can be an effective engagement strategy.

Trainee Content for Day 1, Segment 9

Myths & Research about Sexual Offenders5

There are commonly held beliefs about sexual offenders that are actually myths. Since

the 1970s, empirical data from various sources (research through the National Institutes

of Mental Health, records from Great Britain’s prisons and studies in outpatient clinics in

Great Britain and the USA) has improved our knowledge about sexual offending and

undermines these myths (Abel, Mittleman, Cunningham-Rather, Rouleau, & Murphy,

1987; Abel & Harlow, 2001).

1. Molesters usually have a particular type of victim they look for and are probably

not dangerous to children who don’t fit the profile (e.g., only molest boys, only

young girls, etc.).

In the 1970s, Gene Abel, MD and colleagues collected extensive data on 533 convicted

sex offenders in their Atlanta and New York clinics. These men received immunity from

prosecution and their names and information were sealed. Even with these protections,

the belief is that they underreported their offenses. Nonetheless, the findings from this

landmark study were astonishing:

62.5% of men who had molested a male had also molested a female.

23% of men who molested a female had also molested a male.

Of men who were convicted for molesting adolescents, 100% admitted to molesting

adolescents, 68% admitted to also molesting children, and 45% had also raped adults.

Of men who were convicted for raping adults, 100% admitted to raping adults, 49%

admitted to also molesting children, and 39% had also molested adolescents.

Of men who were convicted for molesting children, 100% admitted to molesting

children, 43% admitted to also molesting adolescents, and 34% had also raped adults

(Abel, et al., 1987).

A study from the British Penal System also found a very high degree of crossover in both

gender and age. For example, when the initial victim was a male child, 1 out of 3 men

who were subsequently rearrested victimized a female; when the initial victim was a

female, one-fifth was rearrested for a molest of a male child (Thornton, 2000).

5

The material on sexual offenders has been in part provided Miriam Wolf (Child Sexual

Abuse) and Niki Delson (www.delko.net).

Abel & Harlow (2001) later conducted a larger study with a sample of 3,952 admitted

child molesters and found:

Of the pedophiles who molest girls, 21% also molest boys. Of the pedophiles who

molest boys, 53% also molest girls.

Male molesters whose preference is for adolescent males (14-17 years old),

“ephebophiles”, frequently become involved with other children. A study of over 600

male ephebophiles found that slightly over 50% also had a history of molesting boys

under age 14. In addition, over 28% had molested girls under age 14, and 20% had

molested girls 14 to 17 years of age.

2. There is a typical “offender profile.”

The Abel & Harlow Child Molestation Prevention Study (2001) highlights the fact there

is no typical offender profile and that child molesters look the same as everyone else.

(Note: Due to small sample size, all females’ data was removed from survey as was the

data for those who molested adolescents above the age of 13. See supplemental handouts

for more information on female perpetrators)

Comparison with Men in the U.S. Population:

Demographics (Admitted child molesters N = 3,952, Ages: 18 to 95, average age 38.5)

U. S. Males

Admitted Child

Molesters

Married or formerly

married

Some college or higher

education

High school graduate

73%

77%

49%

46%

32%

30%

Working

64%

65%

Religious

93%

93%

Ethnicity (2% of the study sample reported they were from none of the represented ethnicities)

U. S. Males

Admitted Child

Molesters

Caucasian

72%

79%

Hispanic/Latin American

11%

9%

African-American

12%

6%

Asian

4%

1%

American Indian

1%

3%

3. Because it is a family problem, incest offenders do not present much danger

outside their families.

From the Abel, et al (1987) study:

65.8% of men who committed sex offenses inside of their families had also

committed sex offenses outside of their families.

From the Abel & Harlow (2001) study:

68% reported they had molested a child in their family. (The 68% is based on

individual men, while each individual man may have molested one child or several

children who were in different family relationships with them.)

o 19% reported molesting a biological child

o 30% reported molesting a stepchild, adopted child (3.3%), or foster child (1.3%)

o 18% reported molesting nieces or nephews

o 5% reported molesting grandchildren

o 12% of perpetrators as teenagers, molested a much younger brother or sister

40% reported molesting the children of their friends or neighbors.

o Nearly 24% of the men who were molesting children in their own family were

also molesting the children of friends and neighbors

o 5% said they had molested “a child left in my care by an organization”

4. Most sexual offenders perpetrate sexual abuse and rape because they were

victims of sexual abuse and are acting out what was done to them.

For many years, there has been an idea of a “victim-to-victimizer” cycle; that sexual

abuse as a child is a powerful risk factor for becoming a sexual offender. However, this

conclusion is not supported by research. Although not entirely without foundation

(somewhere between 20-30% of adult, male offenders do have a sexual abuse history),

most sexual offenders do not have sexual abuse histories. The “victim-to-victimizer”

theory was initially borrowed from physical abuse, where there is a stronger cycle

connection between childhood experiences and adult perpetrator behavior. The notion

was also supported by early retrospective self-report data from incarcerated, adult sex

offenders. This population has some motivation to exaggerate or lie about their abuse

histories, as people may look at their offenses more “kindly” if they are also “victims”.

Studies which attempted to verify these self-reports using polygraphs have demonstrated

that self-reports of victimization are exaggerated.

The rate does appear to be higher for children with sexual behavior problems. However,

most children who were sexually victimized never perpetrate against others. So,

while a sexual abuse history is a factor in individual cases, it does not seem to be

sufficient as a general explanation about why people sexually offend. The causes are

more complex. Research does point to links with childhood histories of physical abuse or

neglect and witnessing domestic violence, as well as other pathways that are similar to

other kinds of violent offending, such as early behavior/conduct problems, delinquency,

alcohol/drug use (Chaffin, Letourneau, & Silovsky, 2002).

Conclusions

There have been many classifications proposed to help categorize and understand the

motivations of offenders and predict recidivism (Cohen, Groth, & Siegel, 1978; Lanning,

2001). Typologies such as “fixated/regressed” and “situational/preferential” were

proposed. While important contributions to the literature, it has become clear that child

molesters are a very heterogeneous group, with different motivations for offending and a

need for varied treatment methodologies. The conclusions we can make are:

There is no single “child molester personality profile.”

Child molestation is usually not an isolated incident; by the time it is discovered, the

pattern is often chronic.

Most offenders are reluctant to admit offenses/deviances other than that for which

they have been caught, but when given immunity, many molesters report victims into

the dozens or hundreds.

Offenders commonly use tactics of manipulation, deception, and denial to seduce

children and to convince others of their innocence.

We cannot assume that children who do not fit the molester’s “victim profile” are not