- Repository@Napier

advertisement

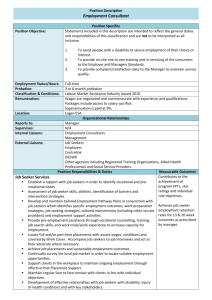

A MODEL OF THE COMMUTING RANGE OF UNEMPLOYED JOB SEEKERS Draft version of: McQuaid, R.W. and M. Greig (2001) “A Model of the Commuting Range of Unemployed Job Seekers”, in: D. Pitfield (ed.), Transport Planning, Logistics and Spatial Mismatch (London, Pion) pp. 152-166. Ronald W. McQuaid and Malcolm Greig Employment Research Institute Napier University South Craig Craighouse Road Edinburgh EH10 5LG Tel. +44 131 455 6033 Fax +44 131 455 6030 r.mcquaid@napier.ac.uk Published in: McQuaid, R.W. and M. Greig (2001) “A Model of the Commuting Range of Unemployed Job Seekers”, in: D. Pitfield (ed.), Transport Planning, Logistics and Spatial Mismatch (London, Pion) pp. 152-166. 2 1. Introduction The ability or willingness of unemployed people to travel further to a new job will affect the level of mismatch between job seekers and jobs (Brueckner and Martin 1997; Gabriel and Rosenthal, 1996; Holzer, 1991). Empirical evidence suggests that a range of socio-economic factors affect the length of time that job seekers are willing to commute to a new job (McQuaid et al, 2001). However, while there is considerable research into the travel-to-work times of those already in work there is limited research on the potential maximum journey to work for unemployed people seeking work. This paper seeks to identify and examine a range of personal, demographic and spatial factors that influence the time that unemployed job seekers would be willing to spend travelling to work if they could obtain employment. In Section 2 existing evidence on factors affecting commuting time is reviewed. Section 3 sets out a theoretical model of the attitudes of unemployed job seekers towards the time they would be prepared to commute to a new job. Section 4 presents the results of a factor analysis of characteristics of unemployed job seekers and their attitude towards travel-to-work times. Section 5 presents the conclusions. 2. Empirical Evidence Considerable existing empirical research has examined factors associated with travelto-work time (e.g. Aronsson and Brannas, 1996) and travel-to-work distance (e.g. Rouwendal and Rietveld, 1994; Ong and Blumenberg, 1998) in the context of employed workers. However, research on the potential travel times of those seeking work is limited. A notable exception is the work by Van den Berg and Gorter (1997) which quantifies the effect of potential travel-to-work time on the unemployed by measuring the reservation wage differential required to offset the disutility of commuting. Van den Berg and Gorter examine the relationship between this disutility and explanatory variables, which they categorise as person-specific, householdspecific and environment-related. Characteristics of job seekers are often classified as personal characteristics (Rouwendal and Rietveld, 1994). These personal 3 characteristics can be subdivided into the four categories of: innate social characteristics; acquired human capital characteristics; financial characteristics which describe the financial position of individuals; and the characteristics of potential jobs that the person may apply for. In addition, the characteristics of the local economy in which the person lives will influence the attitudes of job seekers towards commuting, and these exogenous factors make up a fifth category of factors affecting attitudes towards commuting time. First, the set of social characteristics examined includes gender, where evidence shows that females are likely to incur shorter travel-to-work times than males (Gordon et al, 1989). Turner and Niemeier (1997) argue that this is due to the effects of the household responsibility hypothesis (Johnston-Anumonwo, 1992) in which the greater household responsibility of females leaves less time for commuting. Evidence of this gender effect in employed workers is supported by, for example, Brännäs and Laitila (1992) in studies of the Swedish labour force, and Rouwendal and Rietveld (1994) in an examination of travel-to-work distance in the Netherlands, and Dex et al (1995) in the UK. Mensah (1995) argues that the increased effect of the household responsibility hypothesis among lower income women in the US leads an increased proportion of part time work and therefore less commuting time due to them working on fewer days. However, evidence of a gender difference is not supported by either Van den Berg and Gorter (1997) or by Ong and Blumenberg (1998) who, in a study of welfare recipients in the US, argue that the limited skills and low wages found in this sector of society transcend gender boundaries. Specifically, marital status has been shown to reduce travel-to-work time due to increased household responsibility, although only for females (Turner and Niemeier, 1997). Contrary to this, Rouwendal and Rietveld (1994) found lack of geographical mobility resulted in married workers having higher travel-to-work distances. Responsibility for dependant children has been found to reduce travel-to-work, especially amongst females (Rouwendal and Rietveld, 1994; Turner and Niemeier, 1997). Aronsson and Brännäs found dependant children increased travel-to-work time for both sexes, arguing that the presence of children necessitates a larger home, usually involving a move to a suburban location with a corresponding increase in 4 commuting time. Also children related ties, such as schools, may reduce the propensity to move house when a member of the household changes jobs. It is likely to often be the case that one working household member has a job with time, commuting and other characteristics, which allows them to take primary childcare responsibility during the working part of the week, while the other adult in the household may commute longer, especially if they change jobs. There are two schools of thought concerning the effect of the age of a worker upon travel-to-work. Taylor and Ong (1995) found that travel-to-work time increases with age and argued this was due to an increase in marketable skills and experience with age, resulting in an increased geographical job search area. However, Ong and Blumenberg (1998) found a negative relationship, arguing that this was due to the higher level of marketable skills in older workers enabling them to compete more successfully for nearby jobs. The bulk of research finds that travel-to-work times decreases with age, mainly due to an unwillingness of older workers to travel for long periods (Brännäs and Laitila, 1992; Rouwendal and Rietveld, 1994; Turner and Niemeier, 1997). The issue of race has been found to have a significant effect on travel-to-work by some (Zax and Kain, 1996; Turner and Niemeier, 1997), although Van den Berg and Gorter (1997) found it not to be significant. The population and sample in this study of Eastern Scotland is relatively homogeneous (with under 2% of people classified as ethnic minorities), so this is not a key issue in the current paper. Second, the set of human capital factors includes educational qualifications, for which the research evidence on effects on travel-to-work is mixed. Izrael and McCarthy (1985) found a negative relationship between education and travel-to-work time and Van den Berg and Gorter (1987) find no significant relationship. In contrast Rouwendal and Rietveld (1994) identified a strong positive relationship between academic training and travel-to-work distance. They argue that this is due in part to the increasing separation of areas of employment growth and new residences. This is particularly due to the increased specialisation and segmentation of the labour market 5 resulting in high individual job search radii, and hence higher potential travel-to-work times for skilled workers. Ong and Blumenberg (1998) address these ideas from an individual rather than a macro-perspective, arguing firstly that skill acquisition raises workers into job markets which are fewer in number and more widely dispersed, hence requiring larger search areas. Secondly, they argue that a rise in income leads to a rise in demand for larger homes and hence a move to a more suburban location, further from centres of employment. As a more precise empirical test of the effects of labour market segmentation on travel-to-work time a measure of specific professional and vocational qualifications is included in the analysis below. It is worth noting that Rouwendal and Rietveld (1994) found the possession of higher vocational qualifications to be insignificant, and Van den Berg and Gorter (1997) found the level of work experience to be insignificant. In addition, to controlling for the type of work experience acquired, a variable to distinguish manual from non-manual work is included. The demand for skilled, nonmanual labour has increased in recent years whereas unskilled jobs have been disappearing, especially in inner city locations (Ong and Blumenberg, 1998). While a fairly crude measure, this variable may allow us to isolate the relative strength of the previously mentioned ‘labour segmentation’ effect against any demand side and/or location disadvantage experienced by lower income unskilled workers. To account for any ‘negative’ human capital incurred during unemployment the variable of unemployment duration is included. Van den Berg and Gorter (1997) found the length of unemployment to be insignificant, however, economic literature associates increased unemployment duration with difficulty in obtaining employment (see for example: Layard et al, 1991). This increased difficulty may increase the search radius and hence increase travel-to-work time for any resulting employment. Research has also highlighted the existence of an opposing ‘discouraged worker effect’ (for example, Budd et al, 1988) in which unemployed workers’ search activity decreases with unemployment duration, which may reduce the search radius and hence reduce travel-to-work time. 6 Third, the financial set of variables are designed to provide a measure of the current financial position of the unemployed workers. Research has shown that the propensity to seek work is inversely related to current income (Blomquist and HannsonBrusewitz, 1990). In particular, the relationship between the ratio of state benefits to average earnings (the replacement ratio) and the level of unemployment has been shown to be positive (Minford et al, 1990; Layard et al, 1991). It is expected that higher levels of total household income will reduce incentives to find employment, thus reducing the job search radius and potential travel-to-work time. Evidence on the effect of labour (earned) income upon travel-to-work behaviour amongst employed workers is mixed. Izrael and McCarthy (1985) and Brännäs and Laitila (1992) found that travel-to-work time increased with earnings, while Aronsson and Brännäs (1996) suggest the opposite. They argue that this occurs due to the fact that leisure is a normal good, i.e. as incomes rise more leisure is demanded, so travel time falls to facilitate this. However, to date, research on the effects of non-labour income for the unemployed is lacking. A high level of personal savings may act as a similar disincentive to job search as a high level of non-labour income, with a corresponding negative effect on travel-towork time. However, a high level of savings is an indicator of past wealth as well as current financial security and may therefore be associated with unemployed workers who were previously in higher earning professions. Such individuals may have higher potential travel-to-work times enforced by labour market segmentation, as discussed previously. The ownership of private transport is a significant factor in improving the employment status of welfare recipients (Ong and Blumenberg, 1998). Access to private transport would enable unemployed workers to search for employment outside public transport corridors and may make travel more comfortable, thus widening their job search radius and increasing potential travel-to-work time. In addition, the ownership of private transport may be a proxy for past wealth, equivalent to savings as discussed above, and may similarly increase travel time. Travel by private transport is also usually accepted as being faster, more convenient and often more reliable than 7 public transport (Turner and Niemeier, 1997). However, while likely to increase the distance travelled to work, access to private transport may reduce the time spent travelling. Unemployed job seekers may recognise this and it may be reflected in their stated potential travel-to-work times. The fourth set of factors examined is that of potential job characteristics, which measure the importance unemployed workers attach to specific job features. In particular, the minimum wage the worker is willing to accept, the reservation wage, has been tested in previous research. Blau (1991) found it to be insignificant in the job acceptance decision process. Van den Berg and Gorter (1997) used differences in the reservation wage to measure the utility of travel-to-work time. They found that there are threshold values of reservation wage for which they can state with confidence that an unemployed worker would or would not be prepared to travel for more than one hour. The reservation wage was found to be higher for a high travel-to-work time. It can be argued this particular relationship is of a bi-causal nature in that the wage offered by the employer and that demanded by the job seeker will be influenced by the travel-to-work time. A high travel-to-work time dictates, ceteris paribus, that a higher reservation wage will be required by the unemployed worker, and the higher the reservation wage offered, the longer the worker will be prepared to travel. In addition, it can be argued that the higher the reservation wage required by the worker, independent of travel time (for instance because the individual is well qualified and/or experienced in a profession), the further that individual will expect to have to travel to meet his or her wage requirements. Further potential job characteristics that should be examined are the unemployed workers’ attitudes to shift work, the importance of promotion prospects and the willingness to accept part-time or temporary jobs (Adams et al, 2000). A greater desire to avoid shift work may force job seekers to widen their search radius in order to obtain employment that satisfies their work pattern requirements. However, it may also be the case that such a desire to avoid shift work may stem from substantial levels of family responsibility which, consistent with the household responsibility hypothesis as outlined by Turner and Niemeier (1997), would reduce potential travel-to-work 8 time. The importance of promotion prospects may be expected to increase potential travel time, again because strict criteria for employment should entail a wider search radius. Unemployed workers seeking jobs with promotion prospects may also be younger and seeking work in more skilled occupations, both of which would be expected to increase potential travel-to-work time. Part-time jobs should be associated with shorter travel-to-work times as they involve a higher ratio of work to travel time. Similarly as a new job involves an investment in finding and possibly investing in new means of transport, temporary jobs are likely to be associated with shorter commutes. Fifth, the location characteristics need to be considered. This issue of opportunities for employment and the characteristics of the local economy forms a further category of factors influencing a job seeker’s travel-to-work attitudes, termed below as location issues. Poor accessibility to a potential work location may discourage people from searching or applying for jobs there. Factors such as access to (including car ownership) and cost of transport will be important, as will the availability of different transport modes and potential to integrate work journeys with other trips (for example shopping or taking children to school). The attitudes and practices of local employers and the characteristics of the neighbourhood economy affect opportunities for local job seekers (Adams et al, 2000; Preston and McLafferty, 1999). The accessibility to job opportunities will also be affected by the density of jobs and other factors, such as the number of other job seekers nearer to the jobs (McQuaid et al, 1996). In addition, the flow of information is influenced by distance with different communication channels between employer and job seeker being used at different times in the search process and for different types of jobs (Russo et al, 1996). Hence those living further from job opportunities may be at a disadvantage so they may be willing to travel further to work to open greater numbers of potential job opportunities, or conversely they may become discouraged and stop seeking work. For details of the accessibility measure used, see McQuaid et al (2001). 9 Research has shown that place of residence can have an impact on travel-to-work (DeSalvo, 1985; Ong and Blumenberg, 1998). The inflexibility of certain types of housing tenure limits workers’ ability to move, and this can increase travel-to-work time. Housing tenure is therefore also included as a social factor. So, in areas with high shares of public housing as in the study area (below) the housing characteristics (e.g. owner occupier or renter, public or private) may be important. The variable of private house tenant is included in the current study as this is the group likely to face the highest housing costs and therefore most likely to be caught in a ‘benefits trap’. These various issues are now combined in a basic model. 3. Theoretical Model The length of time that individuals would be willing to spend travelling to work is determined by their utility function. Rational individuals will maximise utility subject to a budget constraint. If we define a workers utility as: = (C, L; Z ) (1) Where C is consumption, L is leisure and Z a set of exogenous factors. These functional determinants of utility are themselves determined by C = c(Y) (2) LE = T - H t - H w (3) LU = T – S (4) Where LE is leisure for those in employment, LU is leisure for those unemployment, Y is household income, T is total time available, H T is hours spent travelling to work, HW is hours spent working and S is time spent searching for employment. For simplicity T includes essential household functions, such as house cleaning, although there may be a trade-off between L and T. Leisure time will be total time minus time 10 spent working or travelling for employed workers, and total time minus time spent on job search for unemployed workers. There is a trade-off involved between leisure and work where the hours worked will increase income and consumption but will reduce leisure time, individuals preferences on this will be dependant upon their own utility functions. The trade-off will also be affected by the intrinsic benefits of different types of leisure activities. Similarly with travel-to-work time, individuals willing to spend less time travelling to work may derive greater utility from a unit of leisure, for example because of specific personal or economic circumstances. Hence, it would be expected that unemployed workers who would be prepared to spend less than a specified time, say up to 30 minutes, travelling to work would exhibit a different set of characteristics from those who would be willing to travel for longer. No continuous travel time data were available. Respondents were asked to state their potential travel times within given ranges corresponding to the values below. As we were dealing with expected travel time, it was felt that any more precise measure given would be subject to a high margin of error. Also many respondents would most likely round to the nearest 15 minutes anyway, so responses may otherwise be inconsistent. We therefore define unemployed job seekers in terms of four potential travel-to-work groups: K = 1 willing to travel up to 30 minutes to work K = 2 willing to travel 31-45 minutes to work K = 3 willing to travel 46-60 minutes to work K = 4 willing to travel over 60 minutes to work. The model simplifies into equation: Ti X i i (5) Where Ti represents the maximum travel-to-work time that an individual i was prepared to travel. X i is the matrix of factors isolated in the factor analysis which may influence the probability that individual i will travel for a longer period each day 11 with a parameter vector and i is a normally distributed random variable which allows for measurement errors and unmeasured effects. The exogenous explanatory variables were selected to represent the broad groups of job seeker attributes as discussed earlier as: social, acquired human capital, financial, potential job characteristics and location characteristics. The complete list of variables is given in Appendix 1. A factor analysis of job seeker attributes was then performed and a regression conducted on these factors, using travel-to-work time as the dependent variable. Factors were extracted using Principal Component Analysis using the Varimax rotation method with Kaiser normalisation, which enhances interpretation of both the factors and the variables within these. The scores (values with respect to each observation) for these factors were then analysed using a censored grouped data regression, taking as a dependant variable travel to work time, measured on a fourpoint scale as defined by the boundaries above. The data are derived from a survey of 306 unemployed job seekers (72% male) carried out in 13 job centres in the Bathgate and Edinburgh travel-to-work areas (TTWAs). All interviewees were seeking full-time work. Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and a financial centre with a TTWA population of around half of a million and Bathgate is a contiguous industrial and mining area with higher unemployment and rural hinterland and a relatively high level of commuting to Edinburgh. Unemployed job seekers were asked about the way they looked for work, what jobs they were looking for, their personal characteristics, and what was the maximum time that they were prepared to spend travelling (one-way) to work each day. 4. Results The factor analysis produced ten main factors that are summarised in Table 1. These factors were chosen according to the Kaiser criterion, with eigenvalues of more than one and they can also be reasonably interpreted (Table 2). Factor 1 profiles job seekers who are willing to travel longer to work (see below) as having a high level of formal 12 human capital: with positive years educated, YEARSED(+), and level of education reached, HEDQUAL(+), educated to degree level, DEGREE(+) but not educated solely to vocational level, SCOTVEC(-). Factor 1 could be interpreted as ‘high human capital’ job seekers as they represent acquired human capital characteristics. Factor 2 represents a job seeker with high income, TOTINC(+), older, AGE(+), with access to private transport, PRTRANS(+), MARRIED(+), with dependants, NDEPS(+) and professionally qualified, PROFDUM(+). Factor 2 could be interpreted as a ‘better-off and settled life-stage’ variable and represents both social and financial characteristics. TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE TABLE 2 ABOUT HERE Factor 3 is a ‘high density location’ variable with high accessibility to job centres in the area, ACC(+), high local job vacancy levels, VACLEVEL(+), employment in the local (postcode) area, PSDEMP(+), and the level of local (postcode) unemployment, PSDU(+). This Factor clearly represents the location characteristics. Factor 4 could be interpreted as a ‘part-time, temporary workers’ variable with willingness to accept part-time, FUTPT(+), and temporary, FUTTEMP(+), jobs, representing job characteristics. Factor 5 is a ‘non-post-school qualified’ variable with people with their highest qualification being advanced level or equivalent High School qualifications, ALEVEL(+), but negatively related with those having only vocational post-school qualifications, SCOTVEC(-). This Factor again represents acquired human capital characteristics. Factor 6 is a ‘female flexible worker’ variable with unwillingness to do shift work, DUMSHIFT(+), female, but negative in terms of needing to work full-time, FUTFT(-), representing job characteristics. Factor 7 is a ‘requiring suitable permanent jobs’ variable in that job seekers perceive their own work quality positively, QUALITY(+), and require a full-time permanent job, FUTPERM(+). This Factor can be interpreted as representing both a combination of acquired human capital and innate characteristics (qualities) and job characteristics. It loads positively against travel time and so is consistent with Factor 4 which loads negatively (see Table 3 below). Examining the components of Factors 4 and 7, it should be noted that FUTPERM is not an inverse of FUTTEMP – these variables test 13 whether a worker is prepared to take a permanent or temporary job respectively and are therefore not mutually exclusive. The presence of these variables in each factor does not therefore lead to collinearity between these factors. An interpretation is that F7 represents job expectations of workers, whereas F4 is a measure of the characteristics of a worker and their geographical location. Factor 8 has wishing to find jobs that offer promotion prospects, DUMPROM(+), use the job seekers skills, DUMSKILL(+), and offer a high expected wage, EXPW(+). Hence, it may be termed the ‘good jobs’ variable and represents job characteristics. Factor 9 is a ‘low skilled and long-term unemployed’ variable with job seekers who are manual workers, MANDUM(+), and have been out of work for a long time, LENGTHU(+). These represent low human capital characteristics. Finally, factor 10 includes high accessibility to job opportunities, ACC(+), and job seekers in private rented housing, PRENT(+), which in the survey area indicates residence in highdensity properties close to centres of economic activity and can be termed ‘city centre dwellers’. These represent location characteristics. A grouped data logistic regression was then carried out upon the factor scores for factors 1-10, using the of length of time job seekers are willing to travel-to-work as the dependent variable. TABLE 3 ABOUT HERE The results (Table 3) show that Factors 6 to 10 ‘female flexible workers’, ‘requiring suitable permanent jobs’, ‘good jobs’, ‘low skilled and long-term unemployed’ and ‘accessible private housing’ respectively are significant in the regression at the 10% or less levels. Factor 1, ‘high human capital’, narrowly misses significance at the 10% level. Factor 6 is the most highly significant in the equation. The interpretation of the significance of this is that job seekers who most closely fit this profile, i.e. are unwilling to do shift work, female and not requiring a full-time job, are, as expected, likely to travel less. Likewise, job seekers who fit the ‘low skilled and long-term unemployed’ profile of Factor 9 are also less likely to travel for long periods, which is consistent with our expectations. 14 Those ‘requiring suitable permanent jobs’ in terms of the job seekers having a high opinion of their own skills and work attitudes, and requiring a full-time job (Factors 7) are more likely to travel longer. Similarly, as is expected in theory, those requiring ‘good jobs’ (Factor 8) in terms of promotion prospects, expected wages and skills needed are more likely to commute longer. Finally, Factor 10, ‘city centre dwellers’, are likely to be young professional people seeking jobs at the high end of the labour market and who are less likely to have family commitments. Although these people live in accessible areas, they may be willing to endure a higher travel time to secure appropriate employment and they recognise the long travel times in city traffic. The other factors are not significant in the regression analysis, but the signs are all as expected. This suggests that the most strongly correlated variables (Factors 1-5) were less influential on travel time. Factor 1, ‘high human capital’, are more willing to travel longer to work as their expected future income (pecuniary and non-pecuniary) should be higher, especially in the long-term. This is consistent with other evidence cited above. Factor 2, ‘better-off and settled life-stage’ similarly represents job seekers willing to travel longer as expected with their higher incomes and access to private transport (although the coefficient here is very small). However, this factor suggests increasing age is linked to willingness to travel, although it is expected to increase with age before declining again in later working life. The next three factors are each associated with a lower willingness to travel longer to work. Factor 3, ‘high density location’, suggests that job seekers profiled as living in areas with high accessibility to centres with high employment and vacancies (and unemployment due to the relatively large population) are willing to travel less, due to the relative abundance of local opportunities. Factor 4, ‘part-time, temporary workers’, suggests that those willing to accept part-time or temporary jobs are less willing to travel. This is expected given the balance between travel and work time in a part-time job and the effort and expense of arranging travel for a temporary job. Factor 5 is a ‘non-post-school qualified’ variable with those not going to Further or Higher Education or who only have vocational qualifications, willing to travel less, again 15 suggesting that greater human capital investment is associated with longer travel-towork. 5 Conclusions The factor analysis has produced results that present a picture which is consistent with a number of expectations identified in the empirical literature in terms of the specific influences upon the job seeker potential travel-to-work times. However, the results of this research expand on this by offering an insight as to how these may be combined and displayed in job seekers within the sample. Ten Factors were identified: ‘high human capital’, ‘better-off and settled life-stage’, ‘high density location’, ‘part-time, temporary workers’, ‘non-post-school qualified’, ‘female flexible workers’, ‘requiring suitable permanent jobs’, ‘good jobs’, ‘low skilled and long-term unemployed’ and ‘accessible private housing’ respectively. All but two of the10 Factors identified fell into only one of the main groups of characteristics set out in the paper: social, acquired human capital, financial, potential job characteristics and location characteristics. Factors 1, 5 and 9 were composed of human capital characteristics, Factors 4, 6 and 8 of job characteristics, Factors 3 and 10 of location characteristics. In two cases there were factors from two sets of characteristics. In the case of Factor 2, ‘better-off and settled life-stage’ job seekers this represented both social and financial characteristics (age, total income, married, private transport, dependants and professional qualifications). Factor 7 was composed of both a combination of innate social and human capital characteristics (own perceived work quality) and job characteristics (requiring a full-time permanent job). When a grouped data logistic regression was then carried out upon the factor scores, Factors 6 to 10 were found to be significant. Of these significant factors, ‘female flexible workers’ and the ‘low skilled and long-term unemployed’ were associated with willingness to travel for shorter times. Factors ‘requiring suitable permanent jobs’, ‘good jobs’, and ‘accessible private housing’ showed a willingness to commute 16 for longer times. The other factors had the expected signs (with higher human capital being associated with willingness to commute longer and lower human capital, parttime and temporary workers or those living in high job opportunity areas being less willing to commute). The significant factors represented high human capital, job and location characteristics. Interestingly, the social factors were not found to be significant. This suggests that greater research is needed to consider the effects of human capital, job and location characteristics on the attitudes towards travel-to-work of unemployed job seekers. Acknowledgements This work arose from a larger project involving John Adams and Andrew Charlesworth-May, without whose help it could not have been completed. The authors would also like to thank an anonymous referee for useful comments. 17 References Aaronsson, T., Brännäs, K., 1996. Household Work Travel Time. Regional Studies 30, 541-48. Adams, J., Greig, M., McQuaid, R.W., 2000. Mismatch unemployment and local labour market efficiency: the role of employer and vacancy characteristics. Environment and Planning A 32, 1841-56. Blau, D.M., 1991. Search for Nonwage Job Characteristics: A Test of the Reservation Wage Hypothesis. Journal of Labour Economics 9, 186-205. Blomquist, N.S., Hansson-Brusewitz, U., 1990. The effects of taxes on male and female labour supply in Sweden. Journal of Human Resources, 25, 317-57. Brännäs, K., Laitila, T., 1992. Modelling and Prediction on Travel Distance by Car. Transportation Planning and Technology 16, 129-43. Budd, A., Levine, P., Smith, P., 1998. Unemployment, vacancies and the long-term unemployed. Economic Journal, 98, 1071-91. Brueckner, J.K., Martin, R.W., 1997. Spatial mismatch: An equilibrium analysis. Regional Science and Urban Economics 27, 693-714. De Salvo, J.S., 1985. A Model of Urban Household Behaviour with Leisure Choice. Journal of Regional Science 25, 159-74. Dex, S., Clark, A., Taylor, M., 1995. Household Labour Supply, Research Series No. 43. Employment Department, Sheffield. Gabriel, S.A., Rosenthal, SS., 1996. Commutes, neighbourhood effects, and earnings: An analysis of racial discrimination and compensating differentials. Journal of Urban Economics 40, 61-83. Gordon P., Kumar, A., Richardson, H.W., 1989. Gender Differences in Metropolitan Travel Behaviour. Regional Studies 23, 499-510. Holzer, H., 1991. The Spatial Mismatch Hypothesis: What has the Evidence Shown. Urban Studies 28, 105-22. Izrael, O., McCarthy, T.R., 1985. Variations in travel distance, travel time and modal choice among SMSAs, Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 19, 139-60. Johnston-Anumonwo, I., 1992. The Influence of Household Type on Gender Differences in Work Trip Distance. The Professional Geographer 44, 161-9. 18 Layard R., Nickell S., Jackman R., 1991. Unemployment, Macroeconomic Performance and the Labour Market. Oxford University Press, Oxford. McQuaid, R.W., Leitham, S., Nelson, J.D., 1996. Accessibility and Location Decisions in a Peripheral Region of Europe - a Logit Analysis. Regional Studies 30, 589-598. McQuaid, R.W., Greig, M., Adams, J., 2001. Unemployed Job Seeker Attitudes Towards Potential Travel-to-Work Times, Growth and Change, 32 (4), forthcoming. Mensah, J., 1995. Journey to Work and Job Search Characteristics of the Urban Poor. Transportation 22, 1-19. Minford, P., Matthews, K., Rastogi, A., 1990. Labour Market and Supply Factors. Quarterly Economic Bulletin, December, 15 Ong, P., Blumenberg, E., 1998. Job Access, Commute and Travel Burden among Welfare Recipients. Urban Studies 35, 77-93. Preston V., McLafferty, S., 1999. Spatial mismatch research in the 1990s: progress and potential. Papers in Regional Science 78, 387-402. Rouwendal, J., Reitveld, P., 1994. Changes in Commuting Distances of Dutch Households. Urban Studies 31, 1545-57. Russo, G., Reitveld, P., Nijkamp, P., Gorter, C., 1996. Spatial aspects of Recruitment Behaviour of Firms: an Empirical Investigation. Environment and Planning A 28, 1077-1093. Taylor, B., Ong P., 1995. Spatial mismatch or automobile mismatch? An examination of race, residence, and commuting in the US metropolitan areas. Urban Studies, 32, 1453-74. Turner, T., Niemeier, D., 1997. Travel-to-work and Household Responsibility: New Evidence. Transportation 24, 397-419. Van den Berg, G.J., Gorter, C., 1997. Job Search and Commuting Time. Journal of Business Economic Statistics 15, 269-81. Zax, J.S., Kain, J.F., 1996. Moving to the Suburbs: Do Relocating Companies Leave Their Black Employees Behind? Journal of Labor Economics 14, 472-504. 19 Table 1 Factor Analysis Results – Rotated Component Matrix Rotated Component Matrixa BATHGATE ACC2 VACLEVEL TOTINC YEARSED AGE MANDUM PRTRANS FEMALE MARRIED NDEPS PRENT QUALITY FUTFT FUTPT FUTPERM FUTTEMP DUMSHIFT DUMPROM DUMSKILL LENGTHU PSDEMP PSDU EXPW PROFDUM HEDQUAL DEGREE ALEVEL SCOTVEC 1 1.438E-02 9.236E-02 .118 -6.95E-02 .935 -.102 -.339 8.123E-02 8.209E-02 -8.01E-02 .129 5.870E-02 -8.23E-02 3.733E-02 9.417E-02 1.085E-02 .131 -4.36E-02 .167 .101 -.123 4.127E-02 -1.83E-02 .110 3.940E-02 .846 .945 5.681E-02 -.439 2 6.508E-03 -4.30E-02 -7.52E-03 .677 1.855E-02 .664 -4.36E-02 .521 -.131 .838 .552 -4.61E-02 5.376E-02 -9.94E-02 .199 9.870E-02 6.589E-02 4.361E-02 -.340 7.356E-02 1.554E-02 4.825E-03 -1.39E-02 .318 .440 -.167 2.860E-03 -1.74E-02 -.276 3 -.105 .645 .605 1.710E-04 6.445E-02 2.938E-03 .121 -4.87E-02 -3.56E-02 9.462E-03 -7.07E-02 4.554E-02 2.318E-03 -1.40E-02 .117 6.308E-02 4.729E-02 9.026E-02 -7.27E-02 7.816E-02 -1.04E-02 .925 .818 -.299 6.538E-02 7.015E-02 4.244E-02 1.260E-02 7.359E-02 Extraction Method: Principal Component Analys is. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. a. Rotation converged in 14 iterations. 4 .742 -7.41E-02 -.439 .173 7.446E-02 -6.50E-02 -.141 .152 .401 2.852E-02 6.509E-02 -7.12E-02 -1.56E-02 -4.21E-02 .659 -9.94E-03 .722 -.156 -7.51E-02 -.257 -3.43E-02 4.315E-02 .134 .260 -.151 .125 1.381E-02 .112 6.101E-02 Component 5 6 -5.11E-02 -.162 -4.74E-02 4.425E-02 .150 .243 .123 .258 .195 -6.71E-02 .163 2.112E-02 -.152 -.140 1.062E-02 -.112 5.556E-02 .554 1.792E-02 1.665E-02 -.125 -7.66E-04 1.450E-02 -8.60E-03 .241 .107 2.986E-02 -.693 4.232E-02 .288 -.274 -.146 .149 -1.33E-02 -7.87E-02 .587 5.771E-02 1.128E-02 .228 .213 2.967E-02 7.091E-02 4.897E-02 2.723E-04 -.120 -2.35E-02 -.160 -.296 -.223 -.188 .169 2.737E-03 -.184 1.045E-02 .872 -5.20E-02 -.589 7.632E-02 7 .233 -.104 6.298E-02 6.356E-02 -5.80E-02 -.142 -2.56E-02 .176 .203 3.501E-02 .181 5.399E-02 .566 .183 -1.41E-04 .695 -.291 7.386E-02 .318 3.169E-02 3.210E-02 3.033E-02 2.931E-02 -6.16E-02 -.326 5.602E-02 -5.17E-02 4.956E-02 .120 8 -.111 8.295E-03 -.200 .124 7.026E-02 .154 -7.10E-02 .195 -6.38E-03 -8.71E-02 -.241 4.892E-03 9.563E-02 6.640E-02 -8.64E-02 -4.44E-02 -1.11E-02 .129 .481 .644 7.269E-02 5.653E-03 2.892E-02 .557 .349 7.316E-02 3.571E-02 6.293E-02 -5.71E-02 9 -2.89E-02 -8.29E-02 -2.57E-02 -2.94E-02 -8.55E-02 .306 .462 -.283 -3.74E-02 -.169 .202 6.092E-02 -2.75E-02 -5.89E-02 -3.28E-02 3.755E-02 -.107 -2.01E-02 -.188 .108 .790 3.965E-03 .114 .106 -3.19E-02 -.242 -4.08E-02 -.118 -.248 10 -.205 .511 4.981E-02 .215 2.587E-02 -6.41E-02 -.102 -.183 8.566E-02 -4.24E-02 -1.70E-02 .857 1.122E-02 -.135 3.841E-02 -3.73E-03 1.549E-02 -.215 .165 -3.33E-02 8.675E-02 .110 -.181 -2.15E-02 -.125 4.308E-02 3.005E-02 1.607E-02 1.725E-02 20 Table 2 Eigenvalues of Extracted Factors Total Variance Explained Component 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Initial Eigenvalues % of Cumulativ Total Variance e% 3.517 12.127 12.127 3.184 10.981 23.108 2.621 9.038 32.146 2.121 7.313 39.459 1.702 5.869 45.328 1.397 4.819 50.147 1.279 4.409 54.556 1.141 3.936 58.492 1.066 3.674 62.166 1.041 3.590 65.756 .965 3.328 69.085 .893 3.079 72.164 .871 3.002 75.166 .844 2.911 78.076 .810 2.792 80.868 .724 2.495 83.363 .697 2.403 85.766 .634 2.186 87.952 .580 2.001 89.953 .558 1.922 91.875 .473 1.632 93.507 .453 1.561 95.068 .377 1.300 96.368 .323 1.113 97.481 .289 .998 98.479 .213 .734 99.213 .160 .552 99.765 5.089E-02 .175 99.940 1.731E-02 5.968E-02 100.000 Extraction Method: Principal Component Analys is. Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings % of Cumulativ Total Variance e% 2.977 10.265 10.265 2.792 9.628 19.893 2.494 8.601 28.494 2.200 7.586 36.080 1.630 5.621 41.701 1.622 5.594 47.296 1.371 4.729 52.024 1.343 4.632 56.657 1.329 4.582 61.239 1.310 4.518 65.756 21 Table 3 Estimated Grouped Data Regression Equation Coefficients for Time Willing to Travel-to-work Factor Characteristics Coefficient estimate F1 ‘high human capital’ Human capital 1.8401 F2 ‘better-off and settled life-stage’ Social and financial 0.0299 F3 ‘high density location’ Location -1.5746 F4 ‘part-time, temporary workers’ Job -0.6018 F5 ‘non-post-school qualified’ Human capital -0.2427 F6 ‘female flexible workers’ Job -4.5691*** F7 ‘requiring suitable permanent jobs’ Human capital/social, job 2.2834* F8 ‘good jobs’ Job 2.7644** long-term Human capital -2.9543** F9 ‘low skilled and unemployed’ F10 ‘accessible private housing’ Constant *** significant at 1% level ** significant at 5% level *significant at 10% level Location 2.3606* 51.394*** 22 APPENDIX 1 DEFINITION OF VARIABLES TTWT = job seeker’s maximum stated daily travel-to-work time (minutes) All have positive co-efficients except those marked (-). Factor 1 variables YEARSED = years of education HEDQUAL = level of education reached DEGREE = educated to degree level SCOTVEC = vocational qualifications only (-) Factor 2 variables TOTINC = monthly non-earned income AGE = age of job seeker in years PRTRANS = 1 if job seeker has access to private transport, 0 otherwise SINGLE = 1 if the job seeker is single, 0 otherwise NDEPS = 1 if the job seeker has dependent children, 0 otherwise PROFQUAL = level of professional/vocational qualifications from 0 (none) to 3 (advanced) Factor 3 variables ACC = accessibility index measuring travel time from job seeker’s residence to major centres of employment VACLEVEL = level of vacancies in local Job Centre PSDEMP = number employed in postal district PSDU = number unemployed in postal district Factor 4 variables BATHGATE= 1 if job seeker is resident in Bathgate TTWA, 0 if Edinburgh TTWA FEMALE = 1 if the job seeker is female, 0 if male FUTPT = prepared to take part-time job FUTTEMP = prepared to take temporary job VACLEVEL= level of vacancies in local Job Centre 23 Factor 5 variables ALEVEL = highest qualification is school Advanced level or equivalent SCOTVEC = has vocational qualifications (-) Factor 6 variables FUTFT = needing to work full-time (-) FEMALE = 1 if the job seeker is female, 0 if male DUMSHIFT = willing to undertake shift work Factor 7 variables QUALITY = self-perceived quality index of transferable skills FUTPERM = prepared to take a permanent job Factor 8 variables DUMPROM = it is important that a new job has promotion prospects DUMSKILL = it is important that a new job utilises the job seeker’s skills EXPW = expected wage Factor 9 variables MANDUM = 1 if job seeker is seeking manual occupation, 0 otherwise LENGTHU = number of weeks that job seeker has been unemployed Factor 10 variables ACC = accessibility index measuring travel time from job seeker’s residence to major centres of employment PRENT = private rented accommodation Other variables in the factor analysis TOTINC = total household income MARRIED = married