Gender Identity Dysphoria– Legal Issues

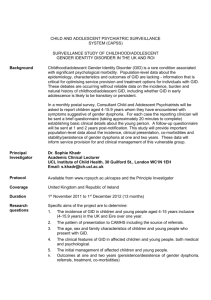

advertisement