The Way of All Youth - Deans Community High School

advertisement

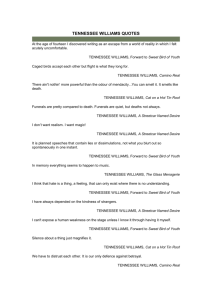

The Way of All Youth (according to Tennessee Williams) At the center of Tennessee Williams’ play “Sweet Bird of Youth” is a middle-aged actress, the Princess Kosmopolis once glamorous, now with a touch of the slut about her. When the curtain came down on her show’s last performance she took up the bottle. Now it’s the morning after and she is in full flight from memory. She’ll never get another casting call; she played her one role and there is no other. She anticipates an endless present of drugs and sex, her only certain “distractions” from painful, vacant reality. Or so she thinks. The hometown boy in her hotel room, Chance Wayne, is half her age, new to the game of gigolo, cute and common, but hardly the beauty of a movie star, the role he wants. She refers to his beauty as the sole source of his claim on an audition with her for a possible Hollywood role. “You got here because of your beauty, you may as well know it.” She dangles the lure, he snaps at it, though he adds a little belligerently, I’ve been conned enough times to be suspicious of a con. She counters dryly with: “It takes one to know one.” This Chance affects an open, rather vacuous face that looks untouched by experience. Very appropriate for the vain boy just beginning to learn how to play himself. But if someone said that Williams wrote the part for Paul Newman–the dates don’t work out as the play premiered on Broadway in 1959– few would argue. The part made Newman as an actor; he defined that moody, sullen attitude that made his beauty dangerous, perhaps even more than the lines say. More, Newman’s undeniable sex appeal put his final stamp on the role and it’s ineradicable. Actors contend with their predecessors; great performances are benchmarks. Williams did not refer much to “Sweet Bird” in his Memoirs, and it falls short in characterization and in dramaturgy of his great accomplishment, “Streetcar Named Desire.” The plays are comparable only in that they feature actresses, Blanche Dubois and Princess, both faded, both sad, their theatrical sense of themselves reflected in their pretentious names. Williams apparently experimented with this type, giving her first an edge of satire, much as if Princess was a rough cut for the far more subtle and touching Blanche. The Princess waves her empty liquor bottle over her head loudly demanding more; Blanche to the contrary suffers from acute self consciousness of her failings including a secret turn to drink. The Princess spells out her need for the “distraction” of sex with Chance; Blanche may know desire but shrinks from Kowalski’s aggressive sexuality. The cast for this production by the Terry Schreiber Studio is first rate and the direction by Terry Schreiber seamless. There is a moment when the frail Aunt Nonnie (Margo Goodman) looks as if she might topple in the breeze made by casual movement of the vigorous young man that she alone welcomes back to town. Such physical contrasts among the actors made for a visually interesting stage. But the play is essentially a simple action of return to beginnings. Chance brings the Princess to visit to his hometown of St. Cloud (nice name for a fantasy place). Her money and glamor may underwrite his illusions, his daydreams of easy success. He also intends to pursue a harebrained His and Hers beauty contest that he and his hometown girl Heavenly Finley will win. The pot will set him up for a new start in life. None of this happens, of course; everyone knows “you can’t go home again.” But it’s interesting that Chance stands apart from his physical perfection so unselfconsciously, seeing and not seeing himself as a commodity. From the opposite point of view, Chance would take a gamble and enact his name. It tells that his identity has no ballast; he belongs to the paying customer and Princess writes out his travelers checks. Perhaps the number of ways Williams will exploit the theme of prostitution in his works begin with “Sweet Bird.” But it’s the related theme that holds power in St. Cloud. The town knows Chance as the boy who deflowered Big Man Finley’s daughter, and so is responsible for having her sent to hospital for a mysterious operation, and skipped out on punishment. The Princess reminds him that penalty would be nothing less than castration; and both they and we are shocked by the mere sound of the word. St. Cloud, nay the South, is a more primitive place than we may recognize. (The play is set “somewhere on the Gulf Coast”) “Sweet Bird” raises the specter of imaginary reprisals arising from violence and horror. In a way, the text’s unspoken reference to brutal events recalls Blanche’s evasive strategies with sexuality in “Streetcar.” Williams’s handling of the subject is elliptical, allusive, suggestive. Chance nags the Princess to telephone a great gossip columnist–in Williams’ time the power of publicity still lay with newspapers–to introduce him and Heavenly into Hollywood’s inner circle. Instead, we learn from the Princess’s lines on the phone that her film has “broken box-office records” and she is still on top. She need not ingratiate herself by offering Hollywood “a beach-boy [I] picked up for pleasure, distraction from panic.” She does not need him at all, except to walk out of the hotel with her since they arrived together and she wants to keep her image straight in the town’s mind. But he remains behind at the hotel. Time, at last, has caught up with the game of riding on her renown: he cannot go on with her. He’s spent his youth and now “something’s got to mean something.” This is more emphatic in report than it was onstage. At times, this Chance, Eric Watson Williams, almost backed away from the role in choosing to underplay Chance’s sexuality, his sine qua non. This left a curious vacancy in the performance; he was not quite there (in Gertrude Stein’s sense of “thereness”), or perhaps better, he did not inhabit the role. Watson left his prettiness to fend for itself. Joanna Bayless (The Princess), to the contrary, was very much “on” and to good effect. Hers is the tricky part, calling for her to be at once worldly and appealing. Her wry tone of voice implies that she still can recover from her “condition,” otherwise “over the hill.” If anything, Bayless might have benefitted from a bit more of the common touch. It’s morning, Easter Morning, with all the symbolism of renewal, and she’s drinking, yet we know her narrow- eyed self appraisal directs her, drunk or sober. She’s a survivor. At curtain up, the balance of power lies with Chance: he is clear-eyed, certainly remembers last night, and holds the original of contracts the Princess signed giving him a screen test. Eventually he realizes with dismay that the papers are phony and she admires his perceptiveness. She almost welcomes him to the con’s inner circle. Church bells are ringing out during his “rebirth” from innocence into experience and it takes instant effect. Princess goes off to her next gig while he for the first time takes a stand alone. Quite apart from their excellent performances, these characters fall short of full dimensionality. Williams seems in this early play to be caught up instead in the violence and horrors of his town, St. Cloud, tightly run by Boss Finley–the name says it all. Chance learns Finley’s gang is out for him and has warned the Princess of imminent danger. Finley represents a nightmarish exaggeration of a law and order racist on a mission from god to purify the South. It seems that after Chance left town a black man suspected of rape was castrated; and Chance’s girlfriend, Heavenly Finley, had to be “spayed like a dawg”; other obscenities are hinted at. He watches on television in horror as a heckler of Boss Finley’s campaign speech is dragged out and beaten nearly to death by Finley’s mob. The television program, by the way, provides a patch of theater within theater in an otherwise straightforward dramatic structure. The secondary characters, all eighteen of them, perform admirably and production values were excellent. A set comprised of subtly colored hanging curtains separating up and down stage also created an elegant, satin bedroom for Acts I and 3. Equally splendid visually, the Princess in Act I Sweet Bird of Youth The Play Sweet Bird of Youth is a 1959 Tennessee Williams play which tells the story of a vigorous but aging movie star trying to recapture her youth, and a driven yet somewhat unscrupulous young man who is seeking stardom and true love. It deals with the classic themes of age versus youth, love versus hate and good versus evil. The original title of the play was "The Enemy, Time," which essentially means the same thing as "Sweet Bird of Youth." "Sweet bird" suggests that, almost before we know it, youth flies away. Youth is sweet and has a buoyant quality, while the enemy, time, is what makes the sweet bird fly. Tennessee was very careful about his titles. The play, which has its lyric and lurid moments at the same time, is about the end of many things, and therein lies the dramatic cliff Tennessee constructs for the viewer: all of the characters are on their last chance. No one escapes having to choose, but it's fascinating to see what each of the characters do when faced with their choice. Chance Wayne is a Hollywood playboy determined to become a star, who teams up with Alexandra Del Lago, a washed-up Hollywood actress, on his way back to his small-town home. The town clamors at the reappearance of the charismatic Chance, who claims to have found fame and fortune in Hollywood, while the mysterious Alexandra lies in a drunken stupor in their hotel room. Alexandra convinces Chance she can make him a star, so he protects her reputation while rediscovering his love for his hometown sweetheart, Heavenly, whose heart he broke when he disappeared to find fame. Chance's attempts to reignite his passion for the naive Heavenly deeply angers her vengeful father, the bigoted politician Boss Finley, who will stop at nothing to see his daughter's lost innocence avenged. Characters Chance Wayne The Princess Kosmonopolis Fly George Scudder Boss Finley Tom Junior Charles Aunt Nonnie Heavenly Finley Pianist Stuff Miss Lucy The Heckler Page Violet Edna Scotty Bud Hatcher The Playwright: Thomas Lanier ("Tennessee") Williams, (1911 1983), was an outstanding American playwright and the author of film scripts, short stories, novels, and verse. He was known for his innovations in theatrical technique, as well as for his Southern idioms, compelling dialogue, and themes that--for their time--often seemed strange or shocking. Williams vividly conveyed the sexual tensions and suppressed violence of his tormented characters, usually with compassion as well as irony. He won Pulitzer Prizes for A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Williams wrote, "At the age of 14, I discovered writing as an escape from a world of reality in which I felt acutely uncomfortable." The form of Sweet Bird of Youth is poetic and the characters in it are larger than life. Tennessee was not a naturalistic writer. He wrote archetypes (Boss Finley, Chance, Heavenly) and there is a Shakespearean sense in his characters being that size. Some of Sweet Bird of Youth's most dramatic moments are like arias, delivered directly to the audience. Tennessee Williams wrote beautiful language in his plays. His compassion for his characters was extraordinary. Chance is certainly not a villain; even Princess, who says she is a monster, finds compassion for him. He was not necessarily a moralist, however. He lays issues out for the viewer, but they don't lead in a particular direction or preach to the audience. The play has religious overtones because it takes place on Easter Sunday; however, it is likely that the rituals and symbols of religion appealed to Tennessee as a dramatist. Much of the humor in the play comes out of tragedy, out of the absurd obsessions of the characters, although Tennessee could also write witty lines for his characters. "I don't think the play is meant to be only about a woman who takes drugs and meets a hustler. I don't believe it ever was about that. But that was the aspect that was shocking in '59. I hope what we can now deal with in this production is the price of success and age and youth and loss of innocence how these elements are part of all our lives. Tennessee knew that time cannot be stopped. That's the tragedy of the play. Things go. Things fade. Things end. It's the central issue of being human and yet in the face of this, a certain nobility can appear. That's what I think Tennessee wrote about." ~ Artistic Director Michael Kahn Themes and Meanings Sweet Bird of Youth is about desperate people clinging to the vain hope that the ravages of time will not touch them, will not take their youth, hopes, and dreams. With Chance and Princess, as with Heavenly and to some extent Boss Finley, the loss of sexual functioning symbolizes this challenge. The play also contains subplots about racial and sexual purity, expressed crudely by Boss Finley and his cronies. The castration of the black man before the play begins is balanced with the impending castration of Chance. These in turn hinge on the quasi-castration of Heavenly by way of her hysterectomy; even Boss Finley experiences a kind of castration as his mistress publicly ridicules him. This emphasis on the brutality of sexual imperfection as an important theme of the play earned for Tennessee Williams savage reviews. Some early critics believed that the lack of emotional content in the relationships overshadowed the use of sex as a metaphor for youth. Despite frequent references to the deep and long-lasting love between Chance and Heavenly, when they do cross paths they do not exchange any word or touch. Moreover, Chance has come to town somehow not knowing that his mother has died and been buried; nor does he know of Heavenly's infection and operation, although he was not prevented from communicating with Aunt Nonnie, for example. The invective of Boss Finley as he crusades for purity, the viciousness of the sexual relationships, and the violence among the men all play into the symbolism of Easter, with its promise of resurrection. The play opens on Easter morning, and the tension-the promise of violence-builds toward a deceptively peaceful ending. Boss Finley states to his faithful that on Good Friday he saw an effigy of himself burned, and on Easter he returns with his message of purity to St. Cloud. The heckler is distinctive in this play as the only voice of conscience. He alone protests the hypocrisy and shame all around him. Notably, when he is beaten the action proceeds without protest. Dramatic Devices One of the striking parallels between the themes of Sweet Bird of Youth and its stage appearance is the bareness of the sets. The stage directions call for a number of special effects that are used to accentuate the starkness of the themes. While the dialogue is at times flowery and rich, the sets are minimalist. The action in different scenes is unified by one cyclorama specified by Williams. Projections of abstract images occur throughout. The most important of these, and the most constant, is a grove of palm trees. Wind plays through the palms, with the sound rising and falling according to the mood of the action, at times interspersed with a musical lament. The images on the cyclorama change somewhat according to the time of day. During the first act, the stage is dominated by a large double bed. There is little else but several incidental props to enrich the Moorish style of the bedroom, and only the suggestion of walls. Thus, the bed, the focal point of the stage, also sets the central theme of sexual interaction. In the first scene of act 2 as well, the action is played against the suggestion of walls, this time on the veranda of Boss Finley's mansion. Williams strongly guides the lighting to a specific paleness-the colors of a Georgia O'Keeffe canvas, he says-as a backdrop to the sinister machinations of Boss Finley. Boss fancies himself a savior, and so all the characters here are instructed to wear white. The telephone ringing, ringing, ringing for Heavenly breaks in to bring the discussion back from the general to the specific. During the cocktail-lounge scene-arranged, again, with the suggestion of a room-Williams specifies that the heckler is to be portrayed as El Greco would portray a saint. The heckler is given a certain pallor, a lanky build, that contrasts with the fullness of build and conventional clothing of the other characters. The others are morally bankrupt, whereas the heckler is constant in his denunciation of Boss Finley's style of rule. During the rally scene, which takes place offstage, the action can still be followed through a curious device: The rally is carried on the television in the cocktail lounge, but the television is larger than life, the projected image taking up an entire wall of the stage set. Although the volume is adjusted up and down, the image of Boss Finley as a deus ex machina is unavoidable. At the climax of the scene, as the heckler is beaten, the action is split: The heckler has fallen into the lounge, but the television image contains Heavenly's reaction. Sweet Bird of Youth was met with derision because of its surfeit of brutality and its alleged sexual perversion, but the integrity of the sets as they reflected the vision of the story only served to reinforce Tennessee Williams's reputation as a dramatic poet. Critical Context Tennessee Williams readily admitted that the sometimes repellent and warped lives portrayed in Sweet Bird of Youth contained much of his own experience. Drugs, alcohol, and promiscuous sex were part of his makeup, and they grew out of the darkly hypocritical society of his native Deep South. This was by no means the first of his plays to expose the hyperbolic vice that had grown into him. The 1959 production of Sweet Bird of Youth came soon after two of his most violent plays, Orpheus Descending (pr. 1957, pb. 1958) and Suddenly Last Summer (pr., pb. 1958). They, too, feature unusual, violent death scenes and bear the theme of personal atonement for social ills. Despite the morbid aspect of much of Williams's theatrical work, Sweet Bird of Youth carries the mark of his early poetic gift. His authentic ear for the language of the South, as well as his innate grasp of the region's rich and complex social fabric, gave each of his plays an appealing glint, no matter how difficult the subject matter. In this respect, Sweet Bird of Youth does not stand out particularly from his other works. Conspicuously missing from this and other late works, however, is the more genteel presentation of plays such as The Glass Menagerie (pr. 1944, pb. 1945). By the time Sweet Bird of Youth was produced, it was clear that Williams drew his characters from a closetful of symbolic figures who appeared repeatedly throughout his literary life-the sexually ungrounded middle-aged woman and the pure young girl, the sinister political boss, the sensitive young man, and so on-each of whom carried his or her heavy emotional baggage. Although Williams's plays seldom visit long in the everyday world, his family of characters inhabits a real world of theatricality.