Enjoyment and Beauty April 30 2011

advertisement

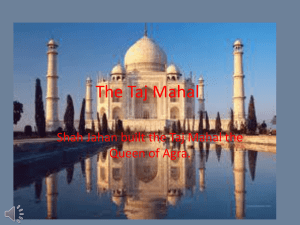

Enjoyment and Beauty We return to the three claims we made earlier. First, one enjoys the items one judges to be beautiful. Second, the enjoyment is a special kind; one does not enjoy in that way items one does not find beautiful. Third, to believe that something is beautiful is to believe, on the basis of the special kind of enjoyment, that others will, other things being equal, enjoy the item in that special way. The First Claim Must one enjoy what one believes is beautiful? The question requires two clarifications. First, there are two ways to read “believes is beautiful”; on one, the claim is false; on the other, true. Second, to enjoy is to enjoy an experience or activity φ under an array A; what are the relevant φ and A? Derivative versus Non-Derivative Judgments of Beauty Why think that when one believes that some item x is beautiful, one enjoys (or has enjoyed, or expects to enjoy) φ under an array of features A, where φ is the experience of an item’s appearing to have the features in A? On one reading of “believes” the claim is clearly false. Imagine that you and Jones are looking that the Taj Mahal. Your enjoyment leads you to exclaim, “Beautiful, isn’t it?” Jones agrees, thereby expressing his own judgment that the Taj is beautiful. Jones, however, does not enjoy looking at the Taj; he never has, and does not ever expect to. He agrees with you because he knows that the received opinion is that the Taj is beautiful, and his 1 agreement acknowledges that the Taj belongs with that diverse collection of items that people generally take to be beautiful. One can in this way judge something beautiful even if has never enjoyed the item and never expects to. Our response rests on a distinction between derivative and non-derivative judgments of beauty. Our claim is that one must enjoy what one non-derivatively judges to be beautiful. When Jones judges the Taj beautiful, his judgment is derivative. A judgment of beauty is derivative if and only if it is based solely on the reports of others. We intend the “solely” to exclude cases in which the reports of others provide one with reason to think one will enjoy something, and in which one judges it beautiful on the basis of one’s own possible future enjoyment. Suppose, for example, that, Arthur sends the following text message to Gwen, “At Taj. Beautiful! Must see to appreciate.” Gwen, who regards as Arthur as a competent judge whose tastes she shares, assumes that if she were to see the Taj, she would enjoy it and would, on that basis, judge it beautiful. Her post-text-message assertion that the Taj is beautiful is not—in the sense we intend—based solely on Arthur’s report, but on her expectation of her enjoyment and consequent judgment. Not all judgments of beauty are derivative. Our argument assumes that one typically has reasons for a judgment of beauty. Some support for this assumption is in order. To this end, compare the Taj and chocolate. One does not treat the “Taj is beautiful” like “Chocolate tastes good.” If, after a good faith tasting of chocolate under appropriate conditions, you and Jones disagree over whether chocolate tastes good, you will not try to 2 change Jones’ mind. Chocolate tastes good to you but not to Jones, and that is the end of the matter. In contrast, if, after a good faith viewing of the Taj Mahal, you think the Taj is beautiful, and Jones does not, it would neither be out of place nor unusual for you to try to change Jones’s mind by offering him reasons to think the Taj is beautiful. This is not to say that, when one gives reasons for a judgment of beauty, one expects others to infer on the basis of these reasons that the item is beautiful. We defer our discussion of the purpose of reason-giving to Chapter 4. Your “Beautiful, isn’t it?” in response to the Taj is an example of a non-derivative judgment. We contend that, typically, when one nonderivatively judges that something is beautiful, (1) one enjoys an experience φ under an array of features A, where φ is the experience of the items’ looking to one to have the features in A, and (2) at least part of one’s reason for the judgment that the item looks to one to have the features in A. In support, suppose you were required to defend your judgment, you would you would describe the aspects of it that you enjoy. It is your belief that you enjoy the Taj in the way you, not the reports of others, that constitutes your reason for your judgment that the Taj is beautiful. This is typical; one gives reasons for one’s judgment that, for example, a face, painting, statue, or poem is beautiful by indicating the features one enjoys. Typically, when one non-derivatively judges that something is beautiful, one’s reason for the judgment is, at least in part, that one enjoys (has enjoyed, or expects to enjoy) the item in a certain way. It is sufficient for our current purposes simply to note that this is typically true. We defer to Chapter V the 3 discussion of whether this typical truth is also a necessary one; it is only in the context of that chapter that we can fully clarify the relation between judgment, reasons, and enjoyment and thus adequately explain why it matters that one enjoys the item one non-derivatively judges beautiful. Our claim is that when one non-derivatively judges that some item x is beautiful, one enjoys (or has enjoyed, or expects to enjoy) φ under an array of features A, where φ is the experience of an item’s appearing to have the features in A. We first explain what we mean by “appears.” “Appears” We use “appear” as it is used in “Objects in the mirror will appear more distant than they are”; that is, under normal conditions, objects will appear more distant. Our reference to normal conditions assumes that, in a variety of contexts, one can identify factors which alter the way things appear, and that there is widespread agreement that these factors qualify as abnormal. Examples: the colored squares in the abstract painting appear to dance; the (real or painted) ship’s gently full sails appear to mirror the tranquility of the sea; the washerwoman appears to have the face and bearing of a Madonna; the statue of Aphrodite presents the goddess’s flesh as at once marble-hard and humanly soft; the strong diagonal elements in a painting, building, face, or body are broken up to just the right degree to appear just short of being mechanical. The above examples are examples of sensuous appearances. We will not provide any definition or account of the 4 notion of a sensuous appearance; we rely on the above examples to indicate what we mean. The appearance need not be sensuous. When Stephan first encounters Cantor’s diagonal proof of the existence of uncountable sets, understanding dawns simultaneously with the apprehension of beauty as the elements of the proof appear to organize themselves with an astonishing simplicity and clarity, a clarity and simplicity that appears to Stephan to invest him with the power to tame the infinite. The appearance, although non-sensuous, has a force and immediacy analogous to a sensuous appearance. We will call such appearances non-sensuous appearances, and again we rely on examples to indicate what we mean. We offer one more. Sarah reads the following lines from Wallace Stevens’ “Peter Quince at the Clavier”: Beauty is momentary in the mind— The fitful tracing of a portal; But in the flesh it is immortal. The body dies, the body’s beauty lives. Sarah finds the lines beautiful as she sees in the image of immortality in the flesh a simultaneous rejection and endorsement of a Platonic conception of beauty as a Form that shines through physical appearances. This is not to say that she formulates to herself the thought, “The image of immortality in the flesh is a simultaneous rejection and endorsement of a Platonic conception of beauty as a Form that shines through physical appearances”; rather, the image encapsulates this idea with a force and immediacy analogous to Stephan’s experience of Cantor’s argument. 5 Two further points are in order. First, one can be mistaken about the way things appear. Imagine that, as you turn a corner, you suddenly see a modern interpretation of a traditional church constructed entirely out of concrete; you think that the strong diagonal elements appear just short of mechanical. However, when you return the next day, it is plain to you that the elements appear quite mechanical. You attribute your earlier belief to your surprise and consequent unexpected enjoyment at discovering the structure; your sudden enjoyment made you see the building in a more favorable light than you do on your return. When you see the building under more normal conditions, it appears differently. Similar remarks are possible in the case of all the examples. It is indeed typical for us to change our minds about the way things appear on ground that conditions were not normal. Second, the way things appear may vary from person to person even under normal conditions. When you look at the statue, Aphrodite’s body may appear to you to be covered with flesh at once marble-hard and humanly soft, but when Jones looks, the statute may not appear as having flesh at all, but simply as a marble rendition of a human form. Neither you nor Jones need be mistaken about how the statue appears. Under normal conditions, it just appears differently to you than it does to Jones. Non-Derivative Judgments and Enjoyment Now, why think that, when one non-derivatively judges that some item x is beautiful, one enjoys (or has enjoyed, or expects to enjoy) φ under an 6 array of features A, where φ is the experience of an item’s appearing to have the features in A? Reflection on the reasons we give shows why. Suppose you find (non-derivatively judge) beautiful a face I find plain. Why I ask you think it beautiful, you answer, “Look at the curve of the check, don’t you see how it complements the shape of the chin, and look at the expressive eyes and the way a smile plays around the lips.” You are describing the way the face appears to you and urging me to attend to it in a way that might make it appear that way to me as well. In giving your reasons you identify the way the face appears to you, where the appearance you describe is one you enjoy. This illustrates the general pattern: in giving our reasons for a nonderivative judgment of beauty, we identify features which it appears to us to have, where we enjoy its appearing to us to have those features. The Second Claim The second claim becomes: one non-derivatively judges some item x is beautiful, one if, in the relevant special way, one enjoys (or has enjoyed, or expects to enjoy) φ under an array of features A, where φ is the experience of x’s appearing to have the features in A. Call the relevant type of enjoyment it b-enjoyment. We claim that b-enjoyment is a special case of value-enjoyment: x b-enjoys y only if φ is an experience of y’s appearing to x to have the features in the array A, and x value enjoys φ under A. More fully: x b-enjoys y only if φ is an experience of y’s appearing to x to have the features in the array A, and 7 (1) x φ’s, and x's φing causes (2) – (4): (2) (a) x occurrently believes, of φ, under A, that it occurs; (b) and has the felt desire, of φ, under A, that it should occur for its own sake; (3) the belief/desire pair in (2) is a first-person reason under A for x to φ. (4) x occurrently believes that x values φ’s having A. The previous section establishes (1) and (2). We next motivate and explain (3). The First-Person Reason Requirement The easiest way to see that (3) is required is to consider an apparent counterexample. Recall Gouge. Gouge’s intensely religious upbringing instilled in him the conviction that a man should not feel erotic desire for another man. In his adolescence, he nonetheless finds himself sexually attracted to his best male friend, but he regards desire as the work of Satan, who is placing temptations before him, and he resists the desire and attempted to rid himself of it. He would never have offered his erotic desires in regard to his friend, and his belief that his friend would welcome his advances, as a justification for making advances. Gouge may nonetheless enjoy looking at his friend under an array of features A that includes features depicting his Gouge’s perception of his friend’s looks and personality. Gouge may, that is, satisfy these conditions: (1) he looks at his friend, and that experience φ causes him 8 (2) (a) to occurrently believe, of φ, under A, that it occurs; (b) and to have the felt desire, of φ, under A, that it should occur for its own sake. Gouge does not personally-reason enjoy looking at his friend because that requires that he regard the belief/desire pair as providing a justification for looking at his friend. Can’t one imagine Gouge thinking, “He is beautiful”? Suppose Gouge does claim the friend is beautiful. How is he to answer the question, “Why do you find him beautiful”? As we noted earlier, one does indeed have reasons for a judgment of beauty, and those reasons, in Gouge’s case will consist in the features in A. When one judges something beautiful, one is willing to offer the enjoyed features as a justification for the judgment. Can he do so without regarding the belief/desire pair as providing a justification for looking at his friend? To assert that something is beautiful is to recommend it as something for both oneself and others to experience, and to so recommend it is surely to regard the belief/desire pair as providing a justification. As we argued earlier, to judge that something is beautiful is to be prepared, on the basis of one’s enjoyment to recommend it as something for both oneself and others to experience. Kandinsky’s famous conversion to abstract painting illustrates the point. Kandinsky writes that It was the hour of approaching dusk. I came home with my paintbox after making a study, still dreaming and wrapped up in the work I had completed, when suddenly I saw an indescribably beautiful picture drenched with an inner glow. At first I hesitated, then I rushed toward this mysterious picture, of which I saw nothing but forms and colors, and whose content was incomprehensible. Immediately I found the key to the puzzle: it was a picture I had painted, leaning against the wall, standing on its side. The next day I attempted to get the same 9 effect by daylight. I was only half-successful: even on its side I always recognized the objects, and the fine finish of dusk was missing. Now I knew for certain that the object harmed my paintings.1 Let φ be Kandinsky’s experience of the painting looking to have an array of features A, the features Kandinsky characterizes as “nothing but forms and colors . . . whose content was incomprehensible.” Kandinsky enjoys φ under A. That is, φ causes him to believe, of φ, under A, that it is occurring, and to desire, of φ, under A, that it should occur for it own sake. The belief desire pair also serves as a first-person reason. He “rushed toward this mysterious picture” in part because he had a reason to experience the way it looked. The role of the pair as a first-person reason also forms part of the explanation why he attempted to reproduce the effect the next day; he generalized to the conclusion that similar belief/desire pairs would be firstperson reason to have similar experiences. Causation Why require that the experience of the item’s looking to have the features in the array A cause the belief/desire pair to serve as a first-person reason? The reason parallels the reason for including the requirement in the definition of first-person reason generally. The reason is that requirement partially explains the power beauty can exercise. It explains in part why, for example, one continues to read the novel even though it is late at night and one must be up early in the morning, and why one cannot tear oneself away from Michelangelo’s David. The power of the enjoyment of what one finds 1 Hahl-Koch, Kandinsky, p. 159. 10 beautiful consists in part in invoking the authority of reason by making one think, “This is justified.” The experience testifies to its own justification. In doing so, the enjoyment of what one finds beautiful shares with first-person reason enjoyment generally the power to capture one in a feedback loop. To illustrate these themes, consider an example in which the causal relation fails to obtain. An elderly museum curator is enjoying looking at his favorite Gauguin. The relevant belief/desire pair functions as a first-person reason to look at the painting, but the experience of looking does not causally sustain that reason. It used to; in his youth, one look at the painting would rivet his attention on it. But now to look at the painting is to be reminded of his youth and of the comparative shortness of the rest of his life. The painting is powerless to hold these thoughts at bay; indeed, power the painting now has is the power to spark unpleasant reflections, and the curator turns away from the painting in the hope that the reflections will more quickly run their course. Far from causally sustaining his first-person reason to look at the painting, the experience of looking at the painting gives him first-person reason to turn away. The curator’s experience is far removed from what Keats describes at the beginning of Endymion: A thing of beauty is a joy for ever: Its loveliness increases; it will never Pass into nothingness; but still will keep A bower quiet for us, and a sleep Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing. For the curator, the painting not no longer keeps “a bower quiet.” The painting no longer possesses for him beauty’s attention riveting power. That power typically characterizes the enjoyment of what we find beautiful. 11 Valuing For convenience, we restate the proposed necessary conditions for benjoyment: x b-enjoys y only if φ is an experience of y’s appearing to x to have the features in the array A, and (1) x φ’s, and x's φing causes (2) – (4): (2) (a) x occurrently believes, of φ, under A, that it occurs; (b) and has the felt desire, of φ, under A, that it should occur for its own sake; (3) the belief/desire pair in (2) is a first-person reason under A for x to φ. (4) x occurrently believes that x values φ’s having A. What is the rational for requiring (4)? This divides into three questions. Why should they be cases in which one has the relevant belief? What should the belief be occurrent? And, why require that the experience cause it? The Belief Why require that one believe one directly values φ’s having A? Our answer to this question in the previous chapter was that has a profound interest in piecing together a picture of oneself, and in particular those parts of the picture that consist of experiences and activities that one values. Those experiences certainly include experiences of what one finds beautiful. More fully, suppose one non-derivatively judges x to be beautiful; then, one values x’s appearing to one to have the features in the relevant array A. Indeed, one will directly value this. Recall that one directly values an x’s 12 having an array of features A if and only if one regards x’s having A as, in and of itself, a third-person reason to act in ways that contribute to its being the case that x has A. We amend the definition of b-enjoyment accordingly; (4) now reads: (4) x occurrently believes that x directly values φ’s having A. Why directly values? Occurrentness Why require that the belief be occurrent? In the last chapter, we answered that the occurrentness of the belief contributes importantly to the feeling of enjoyment. We offer the same answer here. The occurrentness of the belief that one directly values the experience gives one’s feeling of enjoyment a depth and meaning it would otherwise lack. In this case of beauty, it is precisely this experience that we seek. Causation Why require that he experience or activity cause the occurrent belief? Our answer is that the causal relation adds to the explanation of the power enjoyment can exercise. The power of first-person-reason enjoyments consists in invoking the authority of reason by making us think, “This is justified.” In value-enjoyments the experience or activity additionally invokes the authority of reason by also making one occurrently think “This is 13 something I value,” where in b-enjoyment, the thought is “This is something I directly value.” The Current Definition of B-Enjoyment is not Sufficient Consider the following example. Byron enjoys looking at his wife’s face. He fulfills the conditions (1) – (4) with regard to an appropriate φ and A. He does so because the years of marriage that given this particular appearance a unique place in his heart; however, her face is quite plain, however, and, as Byron acknowledges, no one would regard it as beautiful. Bryon does not, and he does not regard his enjoyment as any reason whatsoever to think otherwise. What addition to (1) – (4) would give Byron grounds for thinking his wife’s appearance beautiful? To see how to work toward sufficient conditions, ask why Byron declines to judge his wife’s face beautiful. The most plausible answer is that he knows the value he places on his wife’s appearance idiosyncratic. He does not expect others to value it in the same way. It is one of the oldest and most compelling insights about beauty that its appeal transcends differences in interests, attitudes, time, and place. “Beauty speaks with a universal voice” It is commonplace to characterize beauty as involving the presentation of the universal in the particular. For Plato, for example, the Form of Beauty shines through the particulars in which participate in it with a unique power to awaken in us a memory of our prior perception of, and love for, the 14 eternal Form itself. Shorn of appeal to the Forms, the claim in Kant becomes that the claim that beauty speaks with a “universal voice”: Whether a dress, a house, or a flower is beautiful is a matter upon which one declines to allow one's judgment to be swayed by any reasons or principles. We want to get a look at the object with our own eyes, just as if our delight depended on sensation. And yet, if upon so doing, we call the object beautiful, we believe ourselves to be speaking with a universal voice, and lay claim to the concurrence of everyone, whereas no private sensation would be decisive except for the observer alone and his liking. To formulate our version of the claim that beauty speaks with a universal voice, suppose you are looking at the Taj Mahal. For some relevant φ and A, you satisfy the conditions (1) – (4). In addition, you think any relevant similar person experiencing the Taj in a relevant similar way would directly value the experience. More fully, you think: there is a group G of relevantly similar others, and collection C of relevant similar arrays of features such that, for any member y in G, there is some array A’ in C such that if the Taj were to look to y to have A’, then y would occurrently believe that y directly values the Taj looking to y to have A’. For us, beauty speaks with a more or less universal voice, depending on the size of the group G. We will require that G be “sufficiently large.” In the next chapter, we discuss at length the issues surrounding the appeal to a “sufficiently large” group and the appeals to relevant similarity. To avoid misunderstanding, we should emphasize that we are not claiming that one must have a relevant group explicitly in mind, or even that—implicitly or explicitly—any relatively definite criteria for membership in such a group. Implicit appeal to a vaguely defined, over-inclusive group may well be the norm. 15 To generalize from the Taj example, let φ be the experience of an item x appearing to one to have the features in an array A. One G-universally values x’s appearing to have A if and only if there is a sufficiently large group G of relevantly similar others, and collection C of relevant similar arrays of features such that, for any member y in G, there is some array A’ in C such that if x were to appear to y to have A’, then y would occurrently believe that y directly values x’s appearing to y to have A’. Then: One b-enjoys x’s appearing to have A only if φ is an experience of y’s looking to x to have the features in the array A, and, for some group G (1) x φ’s, and x's φing causes (2) – (5): (2) (a) x occurrently believes, of φ, under A, that it occurs; (b) and has the felt desire, of φ, under A, that it should occur for its own sake; (3) the belief/desire pair in (2) is a first-person reason under A for x to φ. (4) x occurrently believes that x directly values φ’s having A. (5) x occurrently believes that x G-universally values φ’s having A. To think one values G-universally is to see one’s valuing as dependent on only on the attitudes and interests that define membership in G. The more widely those attitudes and interest are shared, the more closely G approximates all of humanity. The Taj, with its considerable cross-cultural, appeal is an example; from its completion in 1631, an increasingly large and culturally diverse group has enjoyed the Taj and has on that basis judged it beautiful. The larger, more diverse, and more temporally extended the similarity group, the less the recognition of the endorsing reason depends on any person’s 16 idiosyncratic attitudes or interests. It depends only on the shared interests and attitudes defining membership in the group, and on the formation of a relevant belief; moreover, in the case of the Taj, the arrays of features attributed to the Taj tend to be quite similar (focusing on the completely unified presentation of perfect symmetry, simplicity, lightness, complexity, immense detail, and massiveness). Even the formation of the relevant belief seems largely independent of idiosyncrasies. To b-enjoy the Taj is thus to value one’s experience as a contingency-transcending one. Contingency-transcending valuings matter greatly to one. One is immersed we in contingencies. One finds oneself thrown into a particular time, in a particular place; the circumstances in which one is born, raised, and educated, largely shape one’s interests and attitudes; some of these interests and attitudes reflect the peculiarities of one’s unique circumstances and personality, others are shared by smaller or larger groups but are still the product of the contingent conditions and may not be shared by groups formed by other circumstances (New Yorkers take things for granted that Los Angelinos find bizarre, and vice versa). We take it for granted that one has a compelling reason to seek such valuings, to see oneself as having at least partly transcended the web of ruthless contingencies in which one must otherwise live (we do not of course mean to suggest that it is a trivial task to explain why one has compelling reason to seek such reasons). G-universal valuing offers an escape from the contingences that shape us. They allow one to answer the question, “What reason was there for you to experience 17 that?”, by offering a reason the existence of which does not (in one’s eyes) depend on one’s idiosyncratic interests and attitudes. Contingency-transcending valuings are more or less transcendent depending on the size of G. The Taj example illustrates the “more”; the following example illustrates the “less.” William is listening to Son House’s 1965 a cappella rendition of the following verse from the Gospel/blues song, John The Revelator: You know God walked down in the cool of the day Called Adam by his name But he refused to answer Because he's naked and ashamed. William ascribes an array of features to the rendition (concerning Son House’s tone, cadence, the relations of his version to Blind Willie Johnson’s, and so on); he enjoys the verse as having that array, and he judges it beautiful on that basis. He regards the possession of the array as a Guniversal normative reason, where G includes only those who appreciate the blues more or less as he does, who understand the references to Genesis 3: 8 – 10, and who can compare Son House’s rendition to other treatments of the same song, such as Blind Willie Johnson’s. Given such a similarity group, whether someone will value in the same way depends on interests and attitudes that are far less widely shared than the interests and attitudes in the Taj example. We have—we assume—compelling reason to discover Guniversal valuings we share with a like-minded community, even when that community is relatively small. C. Causation 18 In b-enjoyment, the power to causally sustain the relevant active reason is fully present. “A thing of beauty is,” as Keats would have it, a joy for ever: Its loveliness increases; it will never Pass into nothingness; but still will keep A bower quiet for us, and a sleep Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing. Consider this example. An elderly museum curator is enjoying looking at his favorite Gauguin. The relevant belief/desire pair functions as an active reason to look at the painting, but the experience of looking does not causally sustain that reason. It used to; in his youth, one look at the painting would rivet his attention on it. But now to look at the painting is to be reminded of his youth and of the comparative shortness of the rest of his life. The painting is powerless to hold these thoughts at bay; indeed, power the painting now has is the power to spark unpleasant reflections, and the curator turns away from the painting in the hope that the reflections will more quickly run their course. Far from causally sustaining his active reason to look at the painting, the experience of looking at the painting causes him to turn away. The painting no longer “keep[s] a bower quiet . . . full of sweet dreams.” We do not deny that the curator can still judge the painting beautiful on the basis of his present enjoyment; however, we also take it to be clear that, if the painting had never causally sustained an active reason, the curator would have no reason to judge it beautiful. The painting would lack beauty’s attention riveting power. We propose then that one b-enjoys x’s appearing to have A only if x’s so appearing causes (causally sustains) the relevant belief/desire pair’s 19 functioning as an active reason to experience x as appearing to have A. We make essentially the same claim in regard to the belief about directly valuing: one b-enjoys x’s appearing to have A only if x’s so appearing causes (causally sustains) one’s occurrent belief that one directly values x’s appearing to have A. To see that causation is also required here, suppose you and Jones are looking at the Taj; you enjoy it and find it beautiful; Jones enjoys it but does not find it beautiful. Disturbed by his failure to find the Taj beautiful, Jones returns the next day, having spent the prior evening studying expert discussions of the Taj. He looks at the Taj again—armed this time with a thorough knowledge of the features the experts regard as contributing to the Taj’s beauty. When he looks at the Taj, it does indeed appear to him to have the organized array of features the experts identify, and fulfills the proposed conditions for b-enjoying the Taj’s so appearing. That is, he enjoys the Taj’s appearing to have that array; the relevant belief/desire pair serves as an active reason to enjoy the Taj’s so appearing; he occurrently believes that he directly values the Taj’s appearing to him to have A, and believes that he Guniversally values the Taj’s appearing to have A. He has the beliefs, however, only because his reading of the experts has convinced him he should value the Taj in this way. He finds no ground for the beliefs in his own experience. As he says, “The Taj does not speak to me in the way it evidently speaks to others,” and he still does not find the Taj beautiful. He thinks it is a nicely designed building, and he enjoys the harmony of the design, but, as far as he is concerned, the Taj belongs with the wide variety 20 of other things—including tastefully appointed bathrooms, HBO’s Sex and the City, and an immense variety of faces and bodies—that he enjoys as harmoniously designed but does not (non-derivatively) judge it beautiful. He continues to believe that he directly values the Taj’s appearing to him to have A, and to believe that he G-universally values the Taj’s appearing to have A, but the beliefs persists in spite of, not because of, his experiences. Now imagine that, in the midst of his disappointment at not finding the Taj beautiful, Jones notices the unexpected presence of a friend who is also contemplating the Taj. They fall into conversation for some time, and, then, in a lull in the conversation, Jones happens, without thinking about it, to look back at the Taj. He looks without any expectations, without any explicit thought about the expert-identified features which he was scrutinizing earlier. Suddenly, the building speaks to him in a way it did not before: he enjoys its appearing to have the expert-identified array of features, and, this time, its appearing to him to have the features in the relevant array A causes him to believe that he directly values the Taj’s appearing to him to have A, and to believe that he G-universally values the Taj’s appearing to have A. This time the beliefs persist because of, not in spite of his experiences. Jones thinks, “Now I see! It is beautiful!” The experience testifies to its own justification by causing the beliefs about his valuings. Consider another example focused on the belief about G-universal valuing. At age 22, Mason reads Vladimir Nabokov’s novel, Pale Fire. The novel contains a long poem by the—fictional—famous poet, John Shade; the poem is preceded by an introduction by Shade’s friend, Charles Kinbote; 21 Kinbote’s commentary, correlated with the poem’s numbered lines, follows the poem. The poem and Kinbote’s observations comprise a highly allusive and self-referential narrative in which Shade and Kinbote are the characters. Mason enjoys the novel’s appearing to have an array A of features, where the features consist of those involved in his appreciation and understanding of the novels themes of loneliness, alienation, love, self-consciousness, multiple simultaneous viewpoints, the elusiveness of the self, the power and danger of fantasy. The novel’s appearing to him in this way causally sustains his active reason to so experience the novel, and his experience causes him to believe that that he directly values its appearing to him to have A. In addition, there is a group G such that he believes he G-universally Pale Fire’s appearing to have. But he believes this only because he has discovered, from conversations, and from reading reviews and discussions, that it is true. Pale Fire speaks to him so directly about his particular loneliness and alienation that, whenever he reads the novel, he is astonished that it would appear to anyone else in more or less the way it appears to him; indeed, he finds the thought that of its appearing so to others as inconceivable, or he would so regard it if he did not know it was true. In his eyes, the novel is a message from Nabokov to him, to what is unique and idiosyncratic about his experience, experience that is, in his eyes, essentially unknown and unknowable by others. He reluctantly admits that others seem to be receiving a similar message, but the way the novel appears to him when he reads it does not causally sustain that admission; it works against it. 22 Mason reads the novel again when he is 44. He enjoys it as before, and again the way the novel appears to him causally sustains his active reason to so experience the novel, and his conviction that he directly values its so appearing. Further, as before, there is a group G such that he believes he G-universally values Pale Fire’s appearing to have A. This time, however, his experience of the novel causally sustains that belief. He sees his youthful obsession with a unique message as just one more illustration of feelings of isolation and alienation that plagued him when he was young. It is obvious to him now that many readers would respond to the novel by valuing it in way similar to the way he does. If the forty-four year old Mason were asked if Pale Fire was beautiful, he would answer that it was. The twenty-two year old Mason he might also answer that it was, but his answer would not reflect the conviction that he values the way the novel appears in contingencytranscending way that does not depend on his own idiosyncrasies. Just the opposite. He knows others value as he does, but that fact remains a mystery to him. In the case of b-enjoyment, it is not mystery because the enjoyed experience causally sustains that belief that others value in similar ways. A final point is in order. The enjoyment of beauty captures us in a feedback loop: the item’s appearing in a certain way causally sustains an active reason to experience it as so appearing, which may lead one to act in ways which continue the experience, which may continue to cause the relevant belief/desire pair and to sustain that pair as an active reason to have the experience, which . . . One is all the more likely to act on the active reason to have the experience when one believes that one directly 23 values the experience. That belief eliminates doubt about whether the active reason should indeed function as an active reason. A similar point holds for one’s belief the one values G-universally. That belief removes any concern about whether one is investing one’s time and energy in the pursuit of an idiosyncratic passion that others will neither share nor understand. The feedback loop makes it hard to tear one’s eyes away. As we enjoy the work we attend to it, and as we attend to it we may (or may not) discover additional features of the work which give it even greater power for us, which then feeds back into our enjoyment, and so on. The Taj example illustrates the point. The array of features you believe the Taj to have is the initial focal point of your enjoyment; however, as you continue to enjoy the Taj, the array of features you subjectively ascribe to the Taj may increase in number and complexity, and your original enjoyment of the item as having the array A may transform into the enjoyment of the Taj as having the more complex array A’; A’ then becomes the focal point of your continued contemplation and investigation of the Taj, with the result that the array of features you subjectively ascribe to the Taj, which may increase in complexity . . . and so on—until some natural limit is reached (or perhaps, for optimists, once the critical task of understanding the artwork is fully complete). It is worth noting that the changes in the array A that occur as the feedback loop operates may alter one’s conception of the relevant similarity group. As one apprehends the item differently, one may change one’s view about whose responses will parallel one’s own. 24