Enjoyment and Beauty - Chicago

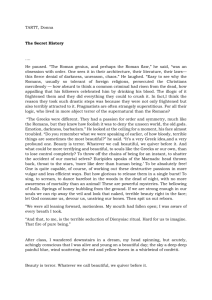

advertisement