Journal of Social History 33

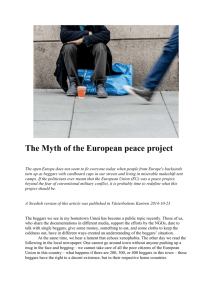

advertisement