Student Union Volunteer Skills Development

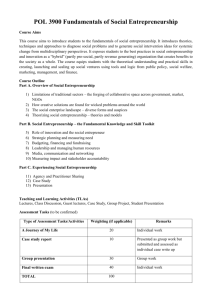

advertisement

UFA module in Enterprise and entrepreneurship Module code E0800BS Andrew G Holmes Centre for Lifelong Learning, Institute for Learning in conjunction with the University of Hull Enterprise Centre STUDY PACK CONTENT Introduction Learning Outcomes and Assessment The underpinning principle of this module Personal Development Planning What assessment evidence do I need to provide? Structuring Your Portfolio What type of evidence is acceptable? How long should my portfolio be? How Are Skills Learnt? The Experiential Learning cycle Questions to ask yourself to aid your skills development Identifying my skills and knowledge Learning logs or a reflective learning journal How do I do know what good reflective writing looks like? Learning Logs – sample learning log Changes Associated with Reflection Questions to ask yourself to help Reflection Skills Audit Skills Audit - Alternative Method Questions to consider What are the behaviours and values that entrepreneurs need? Skills Audit pro forma Gap Analysis Gap Analysis pro forma Useful websites on enterprise and entrepreneurship Reading list - books you may wish to consult CLL Referencing Guidelines Module Specification 1 Introduction This study pack is for anyone who wants to develop their skills in and knowledge of enterprise and entrepreneurship on a part time basis through participation in events organised by or offered through the University of Hull’s Enterprise Centre. When it comes to developing your skills and knowledge the onus is on you to learn, practice and develop them. No one can ‘give’ you the skills to become a successful entrepreneur or a success in the world of work. You have to learn them yourself; though you will learn from and with others. Module Aims In addition to contributing to the overall programme aims for the University Foundation Award this module has the following module-specific aims: 1. to provide students/learners with knowledge of enterprise and entrepreneurship 2. to enable students/learners to identify the key attributes of a successful entrepreneur and engage in personal development planning to develop these skills 3. to facilitate a student’s/learner’s PDP (personal and professional development planning) and reflection on their own skills, abilities and aptitudes as required to successfully engage in enterprise/entrepreneurial activities. Please note that we are not including any definition of what enterprise is here. There are a range of different definitions of enterprise and different categories of enterprise, for example, commercial enterprise and social enterprise. Enterprise for the purposes of this module is a set of attitudes, skills and values which allow you to creatively channel your knowledge. What is the underpinning enterprise/entrepreneurship principle or pedagogy of this module? The underpinning model of enterprise learning for module is of Opportunity-Centred entrepreneurship and Action Learning. 2 Opportunity-Centred entrepreneurship focuses on the learning process of you the individual entrepreneur. Action Learning encourages learning by doing, not just reading about the theory. Reading through this study pack and attending enterprise events at the University of Hull will not make you into an entrepreneur. Only by actively engaging with the learning materials and putting theory and ideas into practice will you start to become an effective entrepreneur and develop the necessary skills and knowledge to become successful. This module encourages you to learn for entrepreneurship and enterprise as well as learning about it. To learn for entrepreneurship and enterprise it is vital for you to learn through direct, practical hands-on experience of doing (Rae 2007). For further information about this process of learning for entrepreneurship and a discussion of it you could read chapter one (opportunity-centred entrepreneurship) in the book Entrepreneurship from opportunity to action by David Rae 2007. Personal Development Planning Participation in this module supports your own Personal Development Planning (PDP) processes. Personal development planning is defined by the quality assurance agency (QAA) as being “a structured and supported process undertaken by individual reflect upon their learning, performance and/or achievements and to plan for their personal, educational and career development” (QAA guidelines for progress files 2001). How do I find out about enterprise events which are happening at the University of Hull? An up-to-date list is available on the website at http://www.hull.ac.uk/enterprise/news_events/seminars_workshop s/index.html 3 LEARNING OUTCOMES The learning outcomes are listed below. You need to demonstrate your achievement of all these learning outcomes in order to successfully pass the module. How well you demonstrate achievement of the outcomes determines the mark you will receive. Your portfolio of evidence needs to show that you have demonstrated all of the areas listed in the table below. On completion of this module students/learners will be able to show that with support and guidance they are able to demonstrate the following learning outcomes: 1. Knowledge and Understanding of: 1i. Key specified aspects of successful enterprise activity. (Note you can specify these aspects yourself or we can specify them for you or we can negotiate them). 1ii. Resources available within the University of Hull to support enterprise activity. 2. Intellectual / Thinking Skills: 2i. Be able to reflect on your own skills and knowledge base and set achievable SMART*goals for enhancing these. 3. Practical / Professional Skills: 3i. Produce a business plan for a business/enterprise idea/concept 3ii Develop skill areas for the individual and/or the organization, as appropriate. (Note you can specify which skills or we can negotiate these) *Specific, Achievable, Realistic, Timebound 4 Assessment Strategy (for 10 UFA credits): This table outlines how your work will be assessed. Assessment method Word count (indicative) Reflective journal (including diary record of attendance at enterprise events) with summary and key points for personal development Written notes Business plan or individual action plan and ideas for your own future enterprise activity** Skills audit 1,100 200 500 ** 40-200 ** whether you choose two and use any business plans or an individual action plan may be determined by with your enterprise activity is social enterprise or commercial enterprise and at what stage you are out with your ideas and planning The word lengths in the above table are there as a guideline only. WHAT ASSESSMENT/EVIDENCE DO I NEED TO PROVIDE? You should provide evidence in the form of a portfolio of evidence which demonstrates your achievement of all of the learning outcomes. The areas you could consider in terms of content are: What is enterprise? Key attributes of an entrepreneur State of mind – the entrepreneurial attitude. Skills for enterprise and entrepreneurship – skills audit Knowledge for enterprise and entrepreneurship – knowledge audit 5 Reflective learning – developing your skills and knowledge Key business start up information. Different types of enterprise, including: for profit enterprises, web-based enterprises, social enterprises, community, and not-for profit enterprises Facilities available and accessing information for your business start up from within and outside of Hull. Social, legal ethical, environmental considerations This may include some of the following: A number of completed reflective learning logs (i.e. keep a reflective learning journal). Completed skills and knowledge analysis/audit A real-time diary record of the number of hours you have spent attending enterprise activity events with a few sentences summarising what the event was about, what you did during it and what you feel you have learnt or gained from it. Evidence to demonstrate you have reflected on your existing skills and knowledge and have engaged in, and with, an ongoing process of learning, in order to further develop your skills and knowledge. Evidence that you have engaged in background reading pertinent to the skill(s) you are developing and that you have related theory to your work, as appropriate. A bibliography of books, papers, websites which you have consulted. When referencing please use the Harvard referencing system. Refer to the CLL referencing guidelines in this module handbook. Evidence of your reading around the subject and of effective referencing a 6 bibliography is necessary in order to gain a good mark. If you need help, advice or information about producing evidence to achieve the learning outcomes please ask your module tutor, Andrew. STRUCTURING YOUR PORTFOLIO OF EVIDENCE There are no hard and fast rules as to what constitutes a portfolio in terms of its size, layout, and content other than that you should produce a portfolio which provides evidence of your knowledge, competency and learning which can be read, understood and assessed against the relevant assessment criteria by somebody else. Your portfolio should not be a disparate set of lots of different pieces of information/evidence. It's not the case that quantity of evidence is important; it is the quality of your evidence which is important. There is a maxim indicative word limit of 2000 words. Things to consider: * Contents page * Introduction – stating what skill area you chose to develop and why * Ring binder with sections/dividers – but please do not put pages into individual plastic wallets. If you do your work will be returned to you and you will need to submit it again. * Clear titles and labelling of sections and pages Whenever you are putting evidence together for your portfolio ask yourself questions of the following type: Will this make sense to the person who will be marking it? (How) Does this evidence demonstrate something? Is this piece of evidence relevant? Does this evidence demonstrate my understanding? Can I prove that this is my own work? Does this evidence my own learning? Does this evidence my own achievement? Is this the best/most appropriate evidence I can put forward? How does this relate to the learning outcomes? 7 WHAT TYPE OF EVIDENCE IS ACCEPTABLE? Broadly speaking, ‘it is up to you’. As long as your assessment evidence is relevant, clear, addresses the assessment evidence criteria and demonstrates your achievement and development in a skill(s), then it should be acceptable. Some examples of evidence include: written reports written self-reflective write ups learning log or extracts from one photographs research evidence diagrams and charts written 3rd party witness testimony (for example someone who has worked with your) written evidence from someone else eg a friend or supervisor project reports spread sheets minutes of meetings where you are mentioned evidence of background reading your thoughts on what you need to do to improve articles, reports etc you have written marketing leaflets you have designed notes you have written The above list is indicative not prescriptive, nor exhaustive. 8 Things to remember Your portfolio should demonstrate how you have learnt, developed and applied knowledge and skills - not just what you can already do and not just the theory of what you have learnt. A successful entrepreneur needs to be able to apply appropriate skills and knowledge. Nor should it be a diary of ‘what I did’. Understanding the theory of something is not the same as actually being able to do it. Read the following quotes: “Theoretical knowledge of the principles involved in a particular…skill is of little use unless the person can apply it in a ‘live’ situation”. (John Payne, 1992, Oldfield Payne Management Associates). “There is a crucial difference between declarative knowledge, knowing a concept and its technical skills, and procedural knowledge, being able to put those concepts and details into action. Knowing does not equal doing, whether playing the piano, managing a team, or acting on essential advice at the right moment”. (Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence 1997) “Understanding and skill rest on each other: as one increases, so does the other. This takes time”. (Genie Z Laborde 1987) You should also indicate how much time you have spent ‘doing it’ But remember that ‘doing something’ is not the same as learning something – you could spend 200 hours doing an activity but learn very little, equally you could spend 2 hours on an activity and learn a great deal. When you are ‘doing’ think about how much you are learning and try and structure your ‘doing’ so that you learn more and apply what you have learnt. Now read the following section ‘How are skills learnt?’ 9 HOW ARE SKILLS LEARNT? This section introduces you to some of the theories of learning and developing a skill and provides an overview of the experiential learning cycle developed by the David Kolb. This is usually referred to as Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. Skills are not necessarily learnt in the same way that other aspects of a course may be learnt. Skills are usually developed in an individual partly by the introduction of theory, but mainly by practice i.e. learning by doing. This is called ‘experiential learning’. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, a variation of which is reproduced below, can be used to see how you learn a skill by doing it, reflecting upon it and learning from it, then planning how you will do it again and then repeating it (doing it again). THE EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING CYCLE (based on material by D.Kolb) HAVING AN EXPERIENCE DO PLANNING (testing your conclusions out) PLAN REVIEW REFLECTING UPON IT LEARN CONCLUDING FROM IT (drawing generalizations) HAVING AN EXPERIENCE = doing something. REFLECTING UPON IT = thinking about it and asking yourself questions such as 'was it good about it?', 'what was bad about it?', 'how well did I do?'. CONCLUDING = learning from your experience and reflection on it. 10 PLANNING = testing your conclusions and generalizations out. Thinking about how you will do it next time and asking yourself questions such as 'how can I do it better?', 'how can I learn from my mistakes?', 'how can I ensure I do the best I can each time?', 'what might I change in the way I did it in order to improve things?'. With many attempts to develop a skill there is usually ample opportunity for ‘doing’ but very little reflection. It is therefore vital to allow time to reflect upon the ‘doing’ phase in order to learn the skill. One way of doing this is via a learning log or journal. “Practice of a Key Skill without feedback can be almost totally ineffective” (Gibbs 1994). For this reason you need to allow time for the practice of your skills and to get feedback on how you are progressing. You could for example obtain feedback from a friend or colleague? You may wish to photocopy the sheets overleaf (or print them out from the website or a CD) to use to help you think about your skills development, or develop your own version if you feel it would be useful to you. The sheets may form part of your assessed portfolio (but they do not have to). But don’t slavishly follow the questions on the sheet. They are designed to help stimulate your own thought process and it’s often useful to modify the questions slightly, or even think of new ones. Treat the questions as something to revisit on a regular basis - don’t just complete the sheets then forget about them. It is also useful to discuss your answers to the questions with one of your friends and ask them to help make suggestions about their answers. 11 IDENTIFYING YOUR SKILLS FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP What skills do you already have and how well do they match what is required? Spend time on this and add to it over time, be specific and think about the general skills you need to be an enterprising entrepreneur and the specific skills you need for your own potential enterprise venture or activity. Be specific, for example if you are considering communication, don’t just put down ‘communication skills’ but think about the type of communication and the context so you may put down things such as communication: negotiation skills on a 1-2-1 basis, negotiation skills in a group, communication, formal presentation skills, communication, informal presentation skills, selling skills etc. Read some books on the different types of communication. Similarly consider the skills of: team-working, time management, ICT (computers skills), mathematics or use of numbers. Spend time on this exercise. By identifying the skills you have and the skills you need you will be able to develop and articulate a plan for developing them. Produce your own version of this table in word or ask for an electronic copy. Try not to overrate your own skills, or underrate them – which is easier said than done. Don’t treat this as a quick one-off exercise. It’s something you should take time over and re-visit week after week as you develop your skills and identify new ones you need to develop. Make sure you read the section after this on the behaviours and values that entrepreneurs need before doing this exercise. The table below is provided as an example of what you could produce to identify your skills. You should produce your own version in MS word and it should be much longer than one below – typically you should aim for 5 or 7 pages of work. This process is part of your own Personal Development Planning (PDP). Of courses it’s a subjective process; but it should get you thinking. A copy of the skills audit is available for you to download from the Internet at http://www.hull.ac.uk/workbasedlearning/ you need to scroll down right to the bottom of the page on this website. Skill How well do they match what’s required? E.g. rate as: very well, well, not so well or rate from 1 to 10 – be honest 12 Some questions to consider after having done your skills audit How well do the skills I have match what is required for my future business/work? Perhaps highlight the areas you need to work on. Set yourself SMART goals for the areas you need to develop in. How and from whom or where will I gain the skills I need? How and when will I make the time to do this? Think about how you are going to gain the skills you need. For example; courses, self study, web searches, mentoring, learning informally from others, shadowing another entrepreneur. An important question! Have you thought about considering things which might be necessary for you possess, but which people often don’t consider to be skills? Things such as: tact, enthusiasm, passion, ‘professionalism’, style, integrity, trust, self promotion? These are things which aren’t necessarily skills; they may be behaviours or values or attitudes and you may need to develop or change yours? What are the behaviours and values that entrepreneurs need? The author Timmons identified in 1999 that there were six attributes and behaviours, and, perhaps more importantly, that they were acquirable i.e. they can be learnt. These six attributes and behaviours are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. commitment and determination leadership opportunity obsession tolerance of risk, ambiguity and uncertainty creativity, self-reliance and ability to adapt motivation to excel The UK’s National Council for Graduate Enterprise (NCGE) has identified a set of learning outcomes which it has for its own framework and which it has published in a document Developing entrepreneurial graduates: Putting entrepreneurship at the centre of higher education ISBN 978-184875-027-2 September 2008 author (Gibb A 2005). 13 You can access a copy at http://www.ncge.com/uploads/Exec_Summary__AllanGibb.pdf see pages 11-12 The following is a modified extract from that document. Listed here are some of the values, behaviours, attitudes and skills which the NCGE feels are important for entrepreneurs. You might want to incorporate some or all of these into your skills audit. You might want to find out more about the meaning of some of them. You may even want to question whether some of them are of use or value to you at the present time? They may not be useful or relevant to you now; but they may be in the future Initiative taking Opportunity seeking Commitment to see things through Networking with other people at different levels Moderate rather than high-risk taking the ability Strategic thinking Negotiation capacity Selling and persuasion Incremental risk-taking Independence Autonomy Imagination High believe that you are in control of your own destiny Need for achievement Achievement orientation Living with uncertainty and complexity Having to do everything under pressure (financial and time) Coping with loneliness Building know how and trust relationships Learning by doing, copying, making things up, problem solving Managing interdependencies Working long hours and unsocial hours Belief that rewards come with your own effort Belief that you can make things happen Belief in individual and the community Motivation to succeed Motivation to make a difference Ability to cope with doing something different to others Ability to see problems as opportunities There is a simple online test which you can do to assess your entrepreneurial capabilities at http://www.palgrave.com/business/rae/students/toolkit_entrepreneurial.html 14 IDENTIFYING YOUR KNOWLEDGE FOR ENTREPRENEURSHIP What knowledge do you already have and how well does it match what is required? Spend time on this and add to it over time, be specific and think about the general knowledge you need to be an enterprising entrepreneur and the specific knowledge you need for your own potential enterprise venture. Be specific, for example, don’t just put down ‘marketing’ but think about the type of marketing such as: poster, internet, local, national. Spend time on this exercise. By identifying the knowledge you have and knowledge you need you can set out on a learning journey to becoming a successful entrepreneur. Produce your own version of this table in word or ask for an electronic copy. Above all be honest with yourself, ask a friend or colleague for honest feedback. Try not to overrate your own knowledge, or underrate it – which is easier said than done. Think about the knowledge you need for your future, both now and in the future (short, medium and long term). Don’t treat this as a quick one-off exercise. It’s something you should take time over and re-visit week after week as you gain new knowledge and identify knowledge you need to gain. The table below is provided as an example of what you could produce to identify your knowledge. You should produce your own version in MS word and it should be much longer than the one below – typically you should aim for 5 or 7 pages of work. This process is part of your own Personal Development Planning (PDP). Of courses it’s a subjective process; but it should get you thinking. A copy of the knowledge audit is available for you to download from the Internet at http://www.hull.ac.uk/workbasedlearning/ you need to scroll down right to the bottom of the page on this website. KNOWLEDGE High/good. Sufficient/adequate, low/poor Or not known at present 15 Some questions to consider after having done your knowledge audit How well does the knowledge I have match what is required for my future business/work? How do I know that my knowledge is sufficient, adequate, accurate and up to date? How will I keep my knowledge up-to-date? How and from whom or where will I gain the knowledge I need? How and when will I make the time to do this? Think about how you are going to gain the knowledge you need. Perhaps highlight the areas you need to work on. Set yourself SMART goals for the areas you need to develop in. There is an online test to assess your managerial capabilities available at http://www.palgrave.com/business/rae/students/toolkit_management.html 16 LEARNING LOGS or A REFLECTIVE LEARNING JOURNAL One way of developing evidence of your skills and knowledge development is to engage in the process of producing a learning log or learning journal. A learning log is basically a record or journal of your own learning. It is not necessarily a formal ‘academic’ piece of work. It is a personal record of your own learning. As such it is a document which is unique to you and cannot be ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, although there are ‘better’ and ‘worse’ ways of producing one. A learning log helps you to record, structure, think about and reflect upon, plan, develop and evidence your own learning. In the context of this module your learning needs to meet certain requirements if you are to achieve the assessment evidence criteria for your chosen skill area. What is a learning log? A learning log or journal is something that you use write down things which you may use as evidence of your own learning and skills development. It is not just a record of ‘What you have done’ but a record of what you have learnt, tried and critically reflected upon. For example in your learning log you could include details of what you did or how you did something and your reflections on this. Becoming a good self-critical reflector is not easy to do. You will probably not become a critical self reflector overnight, and it is a skill that some people seem to be able to do easily, whereas others, particularly people used to a more didactic or directive teaching style, find quite difficult. It often requires time to become comfortable with self reflection. Sometimes it feels uncomfortable reflecting upon your experience(s) and abilities and you may feel that you don’t know whether you are doing it properly. Don’t worry, just practice, or as Nike say ‘just do it’. With practice it becomes easier and you will be more comfortable with the process. Your tutor can help you by providing you with feedback. What do I write in a learning log? Your learning log contains your record of your experiences, thoughts, feelings and reflections about your work and the skills which you are developing. One of the most important things it contains is your conclusions about how what you have learnt is relevant to you and 17 how and when you will use information/knowledge/skill/technique in the future. the new It may contain details of difficulties or issues you have encountered and problems you have solved (or not solved). Examples such as where you have started to try out and practice a new skill, and examples of your own formal and informal learning. Formal learning is ‘taught’ in a formal academic setting - for example via a lecture, or workshop. Informal learning is learning which takes place outside a formal academic setting, for example, through talking with friends or colleagues in a social setting or, for example, through voluntary work. A learning log is a personal document. Engaging in the process will help you to think about and structure your own learning. Once you have commenced a learning log you should find it a valuable and useful 'tool' to help your learning. How do I ‘do’ a learning log? Try to write something down after every new learning experience. Use the sample learning log forms included in this study pack, but don’t feel constrained to use these – change or modify them or develop your own versions if you want to, or work with others to develop your own version. You could identify: What you did Your thoughts Your feelings How well (or badly) it went What you learnt What you will do differently next time. How the above relates to the learning outcomes for the skills area you are working on. On a regular basis (usually 1, 3-5 weekly) review what you have written and reflect upon this. There is no specific timescale. It is up to you. As stated above, what works for one person may not work for another. Be honest with yourself. Ask yourself questions such as: 18 What did I do? Have I achieved anything? If so, what? What progress have I made? (remember sometimes you may make little progress, or even perform less well than last time) Have I put any theory into practice? How does what I have been doing lead to me becoming better at a skill? How can I use this to plan for the future? How can I use this to plan new learning experiences? What did I do? What did I want to do, but did not do? What did I want to say, but did not say? Did it go well? Why? What did/can I learn from this? Did it go badly? Why? What did/can I learn from this? How can I improve for next time? These questions are indicative – you don’t have to specifically answer them; the idea of using them is to get you thinking. One ‘technique’ that the author of this study pack finds useful in helping him to reflect is to sit down in a chair with a large glass or whiskey or whisky or wine and ‘mull things over’ in his mind, asking himself questions similar to the ones above. Try it, the great thing about this is that if a friend sees you and asks you if you are having a drink you can say “No, I’m doing my coursework”! or “No I’m considering the skills I need for my future business success”! Of course, I don’t encourage you to overindulge. You will find that if you begin to ask yourself these questions within 24 hours of having done something (e.g. participated in an event, activity or ‘done’ some planning for your business venture) compared to within, say, 7 days afterwards, then you will find that how you view something, (your perception of it) may be different. Your perception of something changes over time. For example you may have been trying to develop your communication skills and have had a bad or negative learning experience when something went wrong and you feel you have made little or no or even backwards progress. You may reflect upon this the next day and your thoughts and feelings may be mainly negative ones. If you reflect about the experience 3-5 weeks later on you may find that you have now overcome the negative experience and have used it to develop further and improve yourself. Skills rarely suddenly develop or improve ‘overnight’ (but they 19 sometimes do). Learning new knowledge and applying it within a skills context usually takes time, effort and perseverance. At first it may seem difficult to start to critically reflect upon your own learning, over time though, you will find that it becomes easier. The more often that you practice the skill of self reflection then the easier it will become. You can use your learning log to record courses you have attended, books you have read, discussions you have had, Internet sites you have looked at, television programmes you have watched. At the end of the day your log should become something that is directly relevant to you and your learning. If you genuinely engage in the process of critical self reflection via a learning log you really will be able to help your own learning and personal development and go a long way to developing you skills. Is there a ‘best’ or ‘correct’ way of producing a learning log? Not really, the log should be relevant to you and your voluntary activities. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way of producing a learning log. Perhaps the three key questions when engaging in the process of producing a learning log are: Am I being honest with myself? Is this a useful process for me? Is this helping my own process of learning? If you require any help, advice or guidance about your learning log or about how to get started on one then please discuss it with your tutor and with others on the module. How can producing a learning log and developing the skill of critical self reflection help me? Again, that depends very much upon you. Some people will get more out of engaging in the process of producing a learning log than other people will. Research has identified that reflection can help people to change. Some of the changes which have been identified are listed on page 24. How do I know what ‘good’ reflective writing looks like? You may find it useful to read the article at http://escalate.ac.uk/resources/reflection/index.html 20 Also read the articles on the differences between surface and deep learning at http://www.hull.ac.uk/php/cesagh/SURFACEANDDEEPLEARNING.rtf and see the diagram http://www.hull.ac.uk/php/cesagh/LEARNINGASKILL.rtf The learning log template on the next pages is a sample one. You should either photocopy it and use it or produce your won version in MS word. A copy of the learning log is available for you to download from the Internet at http://www.hull.ac.uk/workbasedlearning/ you need to scroll down right to the bottom of the page on this website where you will find a copy of the learning log, the skills audit and the knowledge audit. 21 LEARNING LOG What did I do? E.g. what event did you attend? What did you do there? Who did you speak with? etc How do I think/feel about this? Did I learn anything? Was it a positive experience? How well (or badly) did it go? 22 What did I learn? How or in what way will this help me? What will I do differently next time or in a similar situation? How will I do it differently next time? 23 What have I achieved? What have I learnt: about myself? about my business? About enterprise? (How) have I put any theory into practice? 24 What did I think/feel but not say? What should I have said or asked but didn’t? How can I use this plan for the future? (How) can I use this to plan new learning experiences? What are the key action points I will take away? i.e. what am I going to do next? 25 CHANGES ASSOCIATED WITH REFLECTION From To Accepting Questioning Intolerant Tolerant Doing Thinking Being Descriptive Analytical Impulsive Diplomatic Being Reserved Being more Open Unassertive Assertive Unskilled Communicators Skilled Communicators Reactive Reflective Concrete Thinking Abstract Thinking Lacking Self Awareness Self Aware (Adapted from C Miller, A Tomlinson, M Jones, Researching Professional Education 1994, University Of Sussex). You way want to want to discuss you thoughts and feelings with other budding entrepreneurs who are, like you, students on this module, or with your friends, or the tutor. 26 QUESTIONS TO ASK YOURSELF TO HELP REFLECTION What did I do? How do I think/feel about this? How well (or badly) did it go? Could it have gone better? Or could I have done it better - If so it what way? What did I learn? What did I want to say but did not say? What will I do differently next time? How will I do it differently next time? What have I achieved? Have I put any theory into practice? How does what I have been doing lead to me becoming better at a skill? How can I use this plan for the future? (How) can I use this to plan new learning experiences? What did I think/feel but not say? 27 SKILLS AUDIT A skills audit is a review of your existing skills against the skills you need both now and in the future. It’s an important part of personal development planning. It can help you to identify your existing skills, identify what skills you may need to carry out your existing voluntary work and role more effectively and to plan, develop and improve the skills and knowledge needed for your future career. Carrying out a skills audit for the purpose of this module is a five stage process. Stage 1 - Existing Skills and Knowledge Identification First you write down, as a bullet point list, the knowledge and skills which you consider to be important for your current voluntary work. You may find it useful to refer to the section 'How are skills learnt' to do this and to refer to your ‘job description’ (if there is one for your voluntary work) and to information within the University’s Careers service. Stage 2 - Future Skills and Knowledge Identification Next write down as a bullet point list, the knowledge and skills which you consider to be important for your future career. Each list should comprise roughly between fifteen to twenty bullet points. Stage 3 - Rating Your Ability Once you have produced your lists you need to rate your current ability against each one. This may be done via a 3 point rating of strong, weak and somewhere in-between, or you may find it more useful to use a five point scale such as the one below. 1. = No current knowledge or skill (no current competency), 2. = Some awareness but not sufficiently competent to use it, 3. = Familiar with and able to use the knowledge or skill (some competency), 4. = Proficient in the knowledge or skill and able to show others how to use it (high level of competency), 5. = Expert with a high degree of skill and/or comprehensive knowledge (fully competent). 28 Stage 4 - Review Your Ability Ratings Next ask a friend or your supervisor, or tutor to review your list and give you feedback. Try to ensure that you choose someone who is honest and not afraid to tell you the truth. There is no point in asking a close friend if they are unwilling to be honest for fear that they may hurt your feelings by telling you that you are possibly not as good at something as you think you are. Stage 5 - Your Future Development The final stage is simply that of using the information to concentrate on developing the skill and knowledge areas where you have a low score or have identified that you are not fully competent. SKILLS AUDIT - AN ALTERNATIVE METHOD A more advanced method of carrying out a skills audit is to produce three bullet point lists: 1. Behavioural skills These are the transferable personal and interpersonal skills which are necessary for almost every career. These are typically the skills of: Communication, working with and relating to others, problem solving, communication skills, ITC skills, mathematical skills, self management and development, time management, managing tasks, time management, communicating clearly and effectively, applying initiative. 2. Technical knowledge and skills These are those which are specific to the particular technical/professional area(s) in which you work. For example: if you are doing voluntary work in a school then there may be specific knowledge you may need in order to work with children, or, if you know that your chosen career will be as a counsellor then you will identify that you need to develop specific counselling skills. 3. Other knowledge and skills Those which do not appear on either of the other two lists. They may relate specifically to the area that you do your voluntary work in and may include particular methods and procedures you use or may relate to the position that you occupy and role you carry out. 29 SKILLS AUDIT Knowledge and skills which I consider to Your Ability Rating (1-5) or strong / be important for my future business weak / somewhere in between enterprise Consider numeracy, literacy, written and verbal communication, knowledge of your market, taxation, etc etc 30 GAP ANALYSIS - (Skills Analysis for the future). Another similar process to a skills audit is that of carrying out a gap analysis. A gap analysis is basically the process of matching and comparing the knowledge and skills that you currently have against those that you need for your future role and career and identifying where there are gaps. This matching process can help you to focus better on the skill areas which you need to develop. It’s a tool of personal development planning (PDP). Using the information from your skills audit, think about the voluntary work you do and write down against each of the knowledge and skills on your list the ‘target level’ that you think is required to be fully effective in the job. Next carry this out for the knowledge and skills which you consider to be important for your future career. It is useful at this stage to ask a friend or your tutor, or supervisor to review your list and rate you as well. For example, if one of your required skills for your future career is 'competency in setting up internet home pages' you may have rated you current ability as a 3 (familiar with and able to use the knowledge or skill yourself - some competency). A friend may have rated you as being a 2 (some awareness but not sufficient to use the skill). Ideally you wish to be a 5 (expert with a high degree of skill and/or comprehensive knowledge - fully competent). You therefore have a gap between your existing competency and your required competency. If on the other hand you have rated yourself as a 5, and your friend also rated you as being a 5, then you have no current skills gap in this skill area. If you have used a scale of strong/weak/in between then you may wish to identify your gaps as being small gap/large gap/no gap. Note though that not having a current gap does not mean to say that you will not have a gap in, say, 12 months time - this is particularly the case for information technology based skills where new computer programmes and systems are frequently introduced. You may want to do the same thing for the job position you ultimately aspire to (although many people find long-term planning like this very difficult to do). Thinking about these objectives may mean that you need to add to your list some knowledge and skills which you will need in the future. You may find it useful to consult information in the University’s Careers Service or the Enterprise Centre. 31 GAP ANALYSIS Knowledge and skills which I consider Rating (1-5) or Gap (in points to be important for my current strong, weak, or small, voluntary work in between large, none) Knowledge and skills which I consider Rating (1-5) or Gap (in points to be important for my future chosen strong, weak, or small, career in between large, none) 32 RECOMMENDED READING Due to the nature of this module there are no specific books that you have to read, but your portfolio of evidence must demonstrate that you have engaged in some background reading in order to provide you with greater understanding and underpinning knowledge. You will not be able to gain a good mark unless you engage in and evidence your reading using appropriate quotations and references I recommend that if you wish to purchase one book to help you develop your skills and knowledge then you should buy David Rae’s Entrepreneurship from opportunity to action (2007 Palgrave macmillan ISBN 978-1-4039-4175-6). Useful web sites There is a host of information you can use from internet searches. Some useful sites are listed below. Job match aptitude test at http://www.testcafe.com/job/?affil= Various career and job evaluation tools at http://www.quintcareers.com/career_assessment.html Career management skills web sites hub http://www.agcas.org.uk/employability/career_management_skills/ Business Link Yorkshire – www.businesslinkyorkshire.co.uk – wide range of support materials, training, advice and funding for those starting a business Web sites on Entrepreneurship National Council for Graduate Entrepreneurship http://www.ncge.com/home.php General Entrepreneurship (free downloads of business plans etc) http://www.innovateur.co.uk/key.html Entrepreneurship Education http://ncge.com/content/page/85 Enterprise week http://www.enterpriseweek.org.uk/ Creativity resources from lifehack http://www.lifehack.org/articles/lifehack/essential-resources-for-creativity-163techniques-30-tips-books.html 33 Business Advice http://www.startups.co.uk/UK_entrepreneurship_is_booming.YR-p95JoS63Ijg.html Businessballs website – lot’s of useful resources for business people here http://www.businessballs.com/ Creativity Tools and modelling tools http://www.mindtools.com/pages/main/newMN_CT. http://www.ifm.eng.cam.ac.uk/dstools/ Venture Navigator – business start up advice etc from University of Essex http://venturenavigator.co.uk/ Social Enterprise www.ashoka.org – the Ashoka Social Enterprise network www.globalideasbank.org http://www.leadertoleader.org/ www.socialentrepreneurs.org American National Centre for Social Entrepreneurs The UK Patent Office (Patents, Trade Marks, Registered Designs) http://www.patent.gov.uk/ http://www.prowess.org.uk/ women’s enterprise promotion and support site Reading list - Books you may wish to consult Vass, J. The "Which?" Guide to Starting Your Own Business, Which Books, 2000 Green, J. Starting Your Own Business, How-to Books, 2000 Hingston, P. DK Small Business Guides - Starting Your Business, Dorling Kindersley 2001 Stone, P. Raising Start-up Finance Essentials, 2001 Deakins D, Entrepreneurship and Small Firms, 2nd Ed, McGraw Hill Publishing, 1999 Rae D Entrepreneurship from opportunity to action 2007 Palgrave macmillan If you only read one book about entrepreneurship then read this one. There’s an online student resource site to support David Rae’s book available at http://www.palgrave.com/business/rae/students/ This includes and entrepreneurship toolkit http://www.palgrave.com/business/rae/students/toolkit.html with the following materials: Entrepreneurship toolkit Create a career plan Assess your entrepreneurial capabilities 34 Assess your management capabilities Assess a business opportunity Select a business opportunity (word doc) Build a business model (word doc) Create an action plan (word doc) Information to support venture plan (word doc) Presenting your venture plan (pdf) Financial planner This study pack produced by A.G.Holmes@hull.ac.uk October 2008 35 CLL REFERENCING GUIDELINES Introduction The golden rules of referencing Be consistent – use only the guidelines provided by your department and stick to them for all your work, unless a lecturer tells you otherwise. Follow the detail in these guidelines absolutely, for example punctuation, capitals, italics and underlining. If you do not do this, you may lose marks for your work. Referencing is all about attention to detail! If the source of information you are referencing does not fit any of the examples in your referencing guidelines (see below), choose the nearest example and include enough information for your reader to find and check that source, in a format as close to the example as possible. For further guidance on these types of references, see “Frequently Asked Questions” section (below). Gather all the details you need for your references whilst you have the sources of information in your possession. If you forget to do this and cannot find the sources of information again (they may have been borrowed from the Library, for example, by another reader), you cannot legitimately use them in your essay. If you do so without referencing them, you could be accused of plagiarism. Keep the referencing details you have gathered in a safe place. You can use small index cards for this or an electronic database such as the EndNote program, so that you can sort your references into the order laid down in your guidelines – usually alphabetical by author’s surname. What referencing is Referencing is acknowledging the sources of information (originated by another person) that you have used to help you write your essay, report or other piece of work. In your academic work, you should use the existing knowledge of others to back up and provide evidence for your arguments. The sources of information you use may include books, journal articles (paper or electronic), newspapers, government publications, videos, websites, computer programmes, interviews etc. Why you must reference your sources of information There are: are several reasons why you must reference your work. In no order, these As courtesy to the originator of the material. To provide evidence of the depth and breadth of your reading. To enable your reader to find and read in more detail, a source of information to which you refer in your work. To allow your lecturer/marker to check that what you claim is true; or to understand why you have made a particular mistake, and teach you how to avoid it in future. To enable you to find the source of information if you need to use it again. To avoid accusations of plagiarism. What plagiarism is 36 In its Code of Practice on the Use of Unfair Means (http://www.studentadmin.hull.ac.uk/downloads/code.doc), the University of Hull defines plagiarism as follows: Plagiarism is a form of fraud. It is work which purports to be a candidate’s own but which is taken without acknowledgement from the published or unpublished work of others. (University of Hull, 2004) In other words, plagiarism is using the work of others without acknowledging your source of information; that is, passing off someone else’s work as your own (stealing it). The same Code of Practice lays down severe penalties for committing plagiarism, which is regarded as a serious offence. Further information can be found at http://student.hull.ac.uk/handbook/academic/unfair.html When you must use a reference in your work You must use a reference whenever you: Use a direct quotation from a source of information. Paraphrase (put into your own words), someone else’s ideas that you have read or heard. This is an alternative to using a direct quotation. Use statistics or other pieces of specific information, which are drawn from a recognisable source. How to use quotations in the text of your work Quotations should be used sparingly, for example as primary source material or as evidence to support your own arguments. They should be fairly brief if possible, so that there is room in your work for plenty of your own arguments, not just those of others. When using quotations in your work: Copy the words and punctuation of the original, exactly, except when you wish to omit some words from the quotation. In this case, use three dots … to indicate where the missing words were in the original. If the original has an error, quote it as written but add [sic] in square brackets to tell your reader that you know it is an error but that this is what the original says. Make minor amendments to grammar if necessary, so that your writing and the quotation flow naturally. Put your amendments in square brackets, for example: “In his autobiography, Churchill says that [he] was born at an early age…” The original says “I was born at an early age…” You must also explain how to format and present quotations within the text of your work, depending on your department’s preferences. One example is: If the quotation is a line long or less, incorporate it into your text and enclose it in quotation (speech) marks. If the quotation is longer than a line, put it in an indented paragraph (start it on a new line; indent it at either side; single space it; and do not use quotation (speech) marks). 37 Referencing in the text of your work In the text of your work you are expected to reference your sources of information in an abbreviated (short) format, which signposts your reader to the full details of the sources in your list of references/bibliography at the end of your work (see below). You do not use full references in the middle of your work because they are bulky; they break up the flow of your writing; and they are included in your word count. The Harvard system involves referring to Authors in the text in the following ways. Harris (2003) argues that postmodernism has a dubious future. It has been argued that postmodernism has a dubious future (Harris 2003). The point has been made that ‘it is not easy to see what contribution postmodernism will make in the twenty-first century’ (Harris 2003: 131). At the end of your work the full details for ‘Harris 2003’ would be given in the Bibliography as follows. Harris, J. 2003. The meaning of postmodernism for research methodology, British Journal of Sociological Research. 15:249-66. If you make use of notes or endnotes in an essay, consecutive numbers enclosed in brackets and listed at the end of the essay should identify them in the text. You should make use of this method when citing Web sites. Referencing at the end of your work The references at the end of your work must give the full details of your sources of information, which are signposted from the short references in the text of your work. These full references enable your reader to find and check your sources of information if they wish to. The Harvard system involves the use of a Bibliography only and is the preferred style of referencing for CLL. References are quite rare when the Harvard system is used as the information on sources is firstly contained in the text and then full details are found in the bibliography. You may however use references to indicate that you cannot elaborate on a point but include a reference where a more detailed discussion can be found see example below.1 You may perhaps use a reference to elaborate on some details of your argument - see example 2. The following web page provides a good summary of the Harvard method of referencing http://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/academic_services/documents/Library/Citing_Refer ences.pdf 1 For a general discussion of this problem see, Wright, Levine and Sober (1992). By “material interests” here I simply mean the interests people have in their material standard of living 2 38 A bibliography includes all references, plus all the other sources of information which have been used to assist with the writing of a piece of work, but which are not actually quoted from, paraphrased or referred to in the text of a piece of work. A bibliography shows better than a list of references, how widely a student has read around his/her subject. Using the Harvard method entries should be in alphabetical order of surname, initials and year of publication, title, and publisher. This does not mean that you should include every book and article you have read for the duration of the programme in every Bibliography; you should only include the books and articles you have read in the preparation for that particular assignment. The publication title might be written in italics, in some cases underlining is used (see referencing guidelines below). At the end of an essay all references used should be listed in alphabetical order according to the following guidelines: ELEMENTS OF REFERENCE ORDER OF ELEMENTS AND FORMAT OF REFERENCE Books surname, initials and year of publication, title, place and publisher Young, K., 1999. The Art of Youth Work, Dorset: Russell House Publishing. Chapters in books that are a collection of chapters by different authors surname, initials and Jeffs, T., 1997. Changing their ways: Youth work and year, title. In editor’s “underclass” theory. In R. MacDonald (ed.) Settlements, Social Change and Community Action. Good Neighbours, initials. surname, (ed.) Title, publisher, pages London: Jessica & Kingsley. pp. 231- 239. Printed journal/periodical articles surname, initials., year. Jeffs, T & Smith, M., 2002. Individualisation and Youth Title. journal, volume, Work. Youth & Policy, No. 76. pp 39-65. number, pages Electronic journal/periodical articles as above plus include Neuman, B.C., 1995. Security, payment and privacy for the URL of the electronic network commerce. IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, Vol. 13, No. 8, October, pp. 1523-31. site at which they may be found Extracted from www.IEEE.com Individual work on the web Mandelson, P (1998) Tackling Social Exclusion. Speech, Author's /Editor's name, 14th April 1998, Fabian Soceity, London, extracted from initials., Year. Title . Social Exclusion Unit website( www.cabinet-office), (Edition). Place of www.seu.gov.uk/indix/more.html publication, Publisher (if ascertainable). Extracted from: URL 39 Thesis surname, initials, year of publication. Title of thesis, designation, (and type). Name of institution to which submitted. AGUTTER, A.J., 1995. The linguistic significance of current British slang. Thesis (PhD). Edinburgh University. Videos, films or broadcasts Title, Year. (For films the preferred date is the year of release in the Macbeth, 1948. Film. Directed by Orson WELLES. USA: country of production.) Material designation. Republic Pictures. Subsidiary originator. Yes, Prime Minster, Episode 1, The Ministerial Broadcast, (Optional but director is preferred, SURNAME in 1986. TV, BBC2. 1986 Jan 16. capitals) Production details – place: News at Ten, 2001. Jan 27. 2200 hrs. organisation. Programmes and series: the number and title of the episode should normally be given, as well as the series title, the transmitting organisation and channel, the full date and time of transmission. Frequently asked questions What do I do if there is more than one author? If an item is the co-operative work of many individuals, none of whom have a dominant role, e.g. videos or films, the title may be used instead of an originator or author. If there are two authors the surnames of both should be given:- e.g. Matthews and Jones (1997) have proposed that… If there are more than two authors the surname of the first be given, followed by et al.:e.g. Office costs amount to 20% of total costs in most business (Wilson et al.1997) A full listing of names should appear in the bibliography. 40 What about sources of information with no acknowledged author? For anonymous works use ‘Anon’ instead of a name. What about sources of information which have an editor, not an acknowledged author? Use the following format: Editor surname, initial(s). (ed.) (Year) Title of book, Publisher, Place of publication How do I reference a quotation by an author, which I found as a quotation in a book written by someone else? You should mention the person’s name and you must cite the source author:- e.g. Richard Hammond stressed the part psychology plays in advertising in an interview with Marshall (1999). e.g. “Advertising will always play on peoples’ desires”, Richard Hammond said in a recent article (Marshall 1999, p.67). (You should list the work that has been published, i.e. Marshall, in the bibliography.) If you refer to a source quoted in another source you cite both in the text:e.g. A study by Smith (1960 cited Jones 1994) showed that…(You should list only the work you have read, i.e. Jones, in the bibliography.) If you refer to a contributor in a source* you cite just the contributor:- e.g. Software development has been given as the cornerstone in this industry (Bantz 1995). What do I do if the source of information has no date? If an exact year or date is not known, an approximate date preceded by ‘ca.’ may be supplied and given in square brackets. If no such approximation is possible, that should be stated, e.g. [ca.1750] or [no date]. How should I reference from lecture notes or handouts? You should try to avoid this as much as possible by looking up the information you want to refer to in a textbook or article, preferably recommended by your tutor, and referencing that. If you cannot find the information anywhere else you should reference it with the tutors name as the author , the year , Unpublished lecture notes from... and the date of the class. For individual help with referencing, you can contact the Study Advice Services by email (studyadvice@hull.ac.uk), or: In Hull, make an appointment by telephoning (01482) 466344 or visiting the Study Advice Services Desk on the ground floor of the Brynmor Jones Library (turn left immediately after entering the Library). In Scarborough, make an appointment by telephoning the Library on (01723) 357277 or visiting the Study Advice Services office in room C17b on the first floor of College House (up the stairs near Careers). The Study Advice Services website has a comprehensive leaflet on referencing, available at www.hull.ac.uk/studyadvice. Bibliography HOLLAND, M., 2005. Guide to citing Internet sources. Poole, Bournemouth University. Extracted from: http://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/library/using/guide_to_citing_internet_sourc.html [Accessed 25 August 2005]. 41