Susan Allen`s Alliance columns

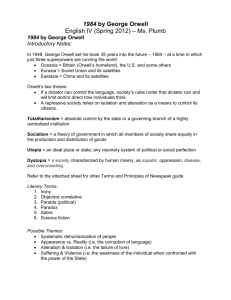

advertisement