B6701A – Strategy Formulation

advertisement

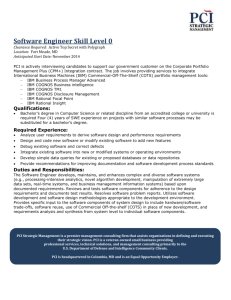

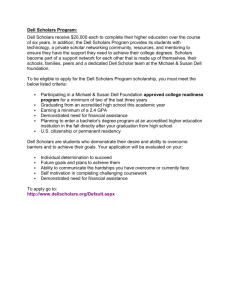

rei B6701A Strategy Formulation Professor Lihua Wang MIDTERM EXAM – Matching Dell CLUSTER Y GROUP 3 Angela Butler Deirdre Eng Alessandro Santo Rei Shinozuka Agam Singh Angela Butler, Deirdre Eng, Alessandro Santo, Rei Shinozuka, Agam Singh February 7, 2005 -1- Angela Butler, Deirdre Eng, Alessandro Santo, Rei Shinozuka, Agam Singh MIDTERM EXAM – Matching Dell 1. How and why did the personal computer industry come to have such low average profitability? The personal computer was designed from the outset as a commodity product, and the market was deliberately engineered to prevent market dominance. IBM laid out the framework of the PC marketplace in such a way that no one, especially itself, would be able to establish a leadership positions by erecting barriers to entry to other vendors. In 1981, IBM a virtual monopolist in the computer industry had vaguely sensed the growing importance of microcomputers. IBM believed that this new segment would represent limited opportunities, but nevertheless did not wish to be cut out of it, and so IBM’s strategy was to create a market for a simple low-margin product in which it could participate. HISTORY IBM believed that success of the new PC would depend on building a critical mass of compatible software and hardware from the microcomputer industry. Phil Estridge, the IBM Vice President credited as the father of the PC, said in 1982: "We believed that a very wide array of software would be one of the key factors in the widespread use of the Personal Computer. There is no way that a single company could produce that much software; even if it were possible, it would take too long. So we needed to have the participation of other software authors and companies." 1 Bill Sydnes, IBM Engineering Manager, echoed: "The definition of a personal computer is third-party hardware and software." 2 COMPLEMENTORS Ironically, while IBM's presence would legitimize the microcomputer market to its customers, IBM's reputation would also threaten the very players in the nascent microcomputer industry IBM needed as partners. Fearing IBM’s dominance in computers, no one wanted IBM as a potential competitor. It was critical that IBM convince these players that they could invest in and profit from this new platform free from fear of IBM's dominance. Estridge's strategy was to define the hardware ISA (Industry Standard Architecture) in which IBM had no proprietary interest. Furthermore, Estridge emphasized that IBM would not change the microcomputer market: "We wanted to fit into what we believed was the existing infrastructure of software houses, authors, hardware vendors, and retail distribution channels that had arisen. We were very anxious to get people to understand that we really did want to fit in and that we weren't trying to set rules for others to live by." 3 Finally, IBM’s PC marketing consciously avoided the strong IBM brand. The PC did not have the traditional IBM product number, and IBM licensed the Charlie Chaplin character to communicate its “kinder and gentler” image.. Nothing within the PC itself was leading edge. The PC was conceived not in IBM's Thomas J. Watson Research Laboratories, but in Boca Raton by a 12-man team headed by Estridge. Their selection of two particular components in the PC would have resounding effects over the next quarter-century, yet were made almost by happenstance. The Intel 8088 CPU was uninspired; in comparison, the Motorola 68000 was a true next-generation design. However, the Intel 8088 was inexpensive, and importantly IBM already possessed a manufacturing agreement to use the 8088 in another product. Similarly, Microsoft's MS-DOS was offered on the strength of that company's well-regarded BASIC language interpreter; Microsoft had never created an operating system. SUPPLIERS http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,1759,1176262,00.asp http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,1759,1163291,00.asp 3 http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,1759,1176262,00.asp 1 2 -2- Angela Butler, Deirdre Eng, Alessandro Santo, Rei Shinozuka, Agam Singh By virtue of IBM’s selection, Intel and Microsoft became single-source suppliers to PC manufacturers, and both companies exploited this position to become extremely powerful forces. By this selection, IBM used its market influence to establish a secure market position not for itself, but on behalf of two then-minor and unthreatening players in the computer world. Vendor support for the new PC was enormous, and soon clone PCs appeared in competition with the IBM PC. Because of the PC's low-tech components, cost of entry was very low. Michael Dell started his business part-time assembling computers while a college freshman. A relatively sophisticated mass production line could be constructed for a $1 million capital equipment. The success and cost-efficiency of the PC market would gradually diminish the role of substitutes in the market, which included Apple computer, but also such diverse players as DEC and Sun and part of IBM and HP’s business. COMPETITION By the time that IBM management recognized the importance of the PC market, the die had been cast, and even IBM was powerless to change the course of PC development. In 1985, Estridge was killed in an airplane crash and IBM management began to reevaluate its PC strategy. In 1987, IBM attempted to strengthen its role in the PC market. IBM introduced MicroChannel as a proprietary and licensed replacement for ISA. On the software front, IBM released OS/2 as an advanced operating system to replace MS-DOS. In response to IBM's moves, in 1988 nine clone-makers led by Compaq formed a consortium to promote an open alternative to MicroChannel. Intel won this skirmish with its PCI standard, still in use today. OS/2 never found an audience, and Microsoft increased its dominance with its Windows OS. The control was rapidly shifting from the PC manufacturers to the "Wintel" Axis. The failure of IBM to assert its control over the PC market in 1987 vindicated Estridge's strategy of the open platform. So long as vendors perceived IBM's control over the industry, they would not play. Ironically Estridge's vision would prove more enduring than IBM's marketing. During the period between 1985 and 1989, IBM saw its market share slide 20 percentage points from 37% to 16.9%, and IBM forever relinquished its influence over the PC industry. Compatibility is the most important characteristic of every PC; it is critical that all PCs run all software precisely the same and interoperate with the same hardware peripherals as the industry standard. So seriously has the compatibility issue been addressed that it is hardly a concern today. Given that compatibility is the prime objective, it is impossible for PC manufacturers to differentiate themselves by way of features. Differentiation by computer performance is also not possible because all manufacturers have access to the same microprocessors, disk drives and other components used to improve performance. The only significant differentiator between the vendors is cost, and customers are very sensitive to price. Customers are in a powerful position since there are virtually no switching costs between PC brands. Given that the cost of supplies is similar for all manufacturers, only the most efficient manufacturer is able to keep internal costs low and either pass on lower costs to the consumer, preserve margins, or a combination of the two. CUSTOMERS 2. Why has Dell been so successful despite the low average profitability in the PC industry? Discuss Dell’s core positioning, strategy and the activities underlying Dell's position and the manner in which they fit together. Dell recognizes itself as a service provider rather than a product manufacturer. In many ways, Dell has more in common with Federal Express than with IBM. Much of Dell's business model hinges upon routing information, components and product quickly and efficiently between -3- Angela Butler, Deirdre Eng, Alessandro Santo, Rei Shinozuka, Agam Singh suppliers and customers. In an environment where computer components decline in value by 2530% per year, or as in 1998 decline 1% per day, Dell's zero-inventory model is not a luxury but a survival factor. The build-to-order model exemplifies the service perspective. In a market where both the finished product and components used in its manufacture are commoditized, Dell differentiates itself from the competition by the manner in which it interacts with the customer through the Dell Direct, and then in the efficiency by which it coordinates convergent delivery of all parts and services needed to land the PC at the customer’s door. Michael Dell explains: "Dell is a company that--from the ground up... started with a very distinctive and different way of doing business." The company is principally an extraordinarily efficient extension of the 18-year old freshman assembling PCs for clients. Much of Dell's success derives simply from what it chooses not to do, and conversely its competitor's failings are a largely a result of a lack of focus as PC manufacturers. The strength of Dell’s direct distribution and zero-inventory model is what it does not have: it does not have resellers or middlemen to squeeze margins, and it does not have costly and wasteful inventory. Dell's competitors distribute product to businesses through valueadded resellers and to home consumers through retail outlets. The inventory and support provided by these channels are prohibitively costly in the low-margin PC marketplace. Rapid obsolescence makes inventory management a large problem, and buy-backs and price protection cost PC makers 2.5% of revenue. Distribution markups and channel advertising cost 5-7% of gross revenue. COMPLEMENTORS By eschewing the middleman, Dell can retain that markup for itself, and replace channel support by contracting this support directly from Xerox, Wang and Unisys. Physical distribution is contracted to UPS and Airborne Express. Dell reduces expensive services typically provided by distribution channels into commoditized services which can be multiply sourced and switched with little cost. In the late 1990's HP and Compaq both attempted to emulate Dell's direct marketing program, but neither would commit to duplicating Dell’s entire business model. They fashioned awkward compromises to create direct marketing portals while pacifying their partners. Rather than recognizing Dell's direct distribution as the face of its service model, HP and Compaq sought to duplicate Dell’s distribution in isolation and graft it onto their existing models. Similarly when attempting to duplicate Dell's zero-inventory model, rivals cut inventory so blindly that they were unable to deliver product. These half-hearted measures not only doomed the new initiatives to failure, but succeeded in alienating resellers into partnerships with generic "whitebox" PC makers or setting up manufacturing operations of their own. Companies with wide product portfolios like HP or IBM depend on the reseller relationship to support their wider product line and cannot afford to alienate resellers. Their wider market scope, often touted as a synergy, is actually a disadvantage versus Dell. COMPETITORS HP and IBM lack Dell’s PC focus. As long-time traditional (non-PC) computer manufacturers they attempted to transplant that business model to PC manufacturing. In traditional computer manufacturing, companies design their own proprietary hardware, operating systems and software. These systems compete primarily on performance and features. The price position is protected because from the customer’s vantage, these systems almost always involve high switching costs. Furthermore, the traditional computer market has a high barrier to entry, since -4- Angela Butler, Deirdre Eng, Alessandro Santo, Rei Shinozuka, Agam Singh new entries must pay high costs for R & D to design proprietary software and hardware, as well as branding and marketing the product. HP and IBM both run expensive R & D programs; HP filed 1,400 patents in 2003. R&D is of limited value in a commoditized industry, and R&D costs have been long dropping in the PC market. As a percent of sales, Dell spends a quarter of what IBM or HP spends on R&D. Dell is more efficient overall, with SG&A and Advertising expenses about half what they are for its rivals, but the difference is striking in R&D. Unlike HP or IBM, Dell has no illusion of itself as a "high-tech company" with its expensive trappings. In the "Wintel" universe, R&D is the province of Microsoft and Intel, and Dell again wins by what it does not do. 3. What, if any, competitive advantages do they have because of the choices they have made? Dell succeeds because the company has self-awareness its rivals lack. Because of this, Dell can concentrate on PC manufacturing. In late 90's, Compaq was busy emulating IBM as a fullservice computer company, and embarking on reckless multi-billion-dollar mergers with Tandem and Digital Equipment while CEO Eckhard Pfeiffer declared: "We want to do it all and we want to do it now." Gateway 2000 was similarly engaged in distracting mergers while losing track of its growing inventory. The trend toward consolidation culminated in 2001 when HP merged with Compaq, resulting in large product overlap which even today remains unresolved. Figure 1 shows the effects of increased expenses and reseller markups in a scenario of Dell versus Compaq and Reseller selling a $1000 PC. Because of the commoditized nature of the products, both cost of components and cost to customer are fixed at $800 and $1000 respectively. Dell is able to extract a 7.6% margin from the transaction, whereas Compaq loses 7.4%. Dell saves $14 by over Compaq by maintaining a smaller inventory, $90 via expenses, and some $60 in reseller markup. By only holding 7 days of inventory, which depreciates at a rate of 25% per year, Dell saves $14 for each PC versus Compaq. Figure 2 shows how Dell and Compaq’s expenses have dramatic effects on profit margins and how close total costs are to revenue (grey bars in front). Expenses and markup tip Dell’s positive margin into Compaq’s negative margin. Compaq is under pressure to increase its prices, or to renegotiate terms with its resellers to reduce their markup. -5- Dell Sale Hardware Components Advertising R&D SG&A Reseller Markup @ 60% Net Income Net Profit Margin Day of Inventory Holding Loss/Year Cost per $1000 sales Compaq & Reseller 1000 800 11 15 98 0 76 7.60% 1000 800 11 43 160 60 -74 -7.40% 7 25% $3.84 34 25% $18.63 Table 1Costs for $1000 PC $1,200 $1,000 $800 $600 $400 $200 Reseller Markup R&D Advertising SG&A Hardware Selling Price $Dell Compaq + Reseller Figure 2 Profit Margin for a $1000 PC