Research Paper for CORPORATE LAWS - I

advertisement

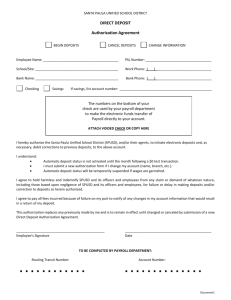

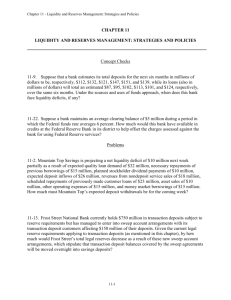

Research Paper in CORPORATE LAWS - I AN ANALYSIS OF THE LEGAL REGIME OF COMPANY DEPOSITS Submitted By Sachin Malhan BLIG 757 2 Table of Contents TABLE OF CASES 3 INTRODUCTION 4 The Coming into Vogue of Company Deposits Thorns in the Side? A Cause for Control RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 6 WHAT CONSTITUTES A COMPANY DEPOSIT 7 What is a Deposit? Constitution of “Public” Loans and Deposits Debentures and Deposits Secured Deposits DEPOSITS EXEMPT FROM THE REGULATORY FRAMEWORK 11 Status of Unclaimed Deposits INVITATION OF DEPOSITS 13 INCORPORATION OF CREDIT-RATING IN DEPOSIT ADVERTISEMENTS CRISIL Ratings 15 FINALISATION OF MATTERS RELATING TO ACCEPTANCE OF DEPOSITS Limits on Amounts Invited for Acceptance 17 The FERA Factor Penalty for Accepting Deposits in Excess of Limits PAYMENT OF INTEREST 19 Penalties for Default REMEDIES FOR REFUND OF DEPOSITS 20 Company Law Board Writ Jurisdiction THE CONTROVERSIAL RULE 3A 21 COMMERCIAL PAPERS 23 CONCLUSION 24 BIBLIOGRAPHY 26 3 Table of Cases Ahmedabad Manufacturing and Calico Printing Co. Ltd. v. Union of India, (1983) 53 Comp. Cas. 904. Annamalai v. Veerappa, AIR 1956 SC 12. Delhi Cloth and General Mills Co. Ltd. v. Union of India, (1983) 54 Comp. Cas. 674. Durga Prasad Mandelia v. Registrar, (1987) 61 Comp. Cas 479. Ittiavira Thomas v. Joseph Tile Works Ltd., AIR 1957 TLC 6. Modi Carpets Ltd., [1991] 6 CLA 152 (CLB). Modi Spinning & Weaving Mills Company Ltd. v. Union of India, AIR 1979 All 221. Pure Drinks (New Delhi) Ltd, Patiala, (1992) 73 Comp Cas 190 (CLB). Ram Janki Devi v. Juggilal Kamlapat, AIR 1971 SC 2551. State of West Bengal v. Union of India, AIR 1996 Cal 181. Vijay Kumar Gupta v. Eagle Paint & Pigment Industries P. Ltd., (1997) 13 SCL 179 (CLB). 4 INTRODUCTION The Coming into Vogue of Company Deposits The early 1960s saw the private sector face a cash crunch. As the five-year plans swung into operation availability of finance to the private sector from traditional resources began to fail to meet the growing demands of the companies. Companies saw deposits from the public as a hassle free and easy way of securing capital. The public that went in for this was happy with the offer since the interests raised were higher than in the case of bank deposits and apparently safer than the fluctuation of share values. Since it was a new practice there were no legal restrictions or procedural hang-ups. More and more corporate enterprises including trading and investment companies went in for this route of raising capital.1 Thorns in the Side? However this apparently pleasant state of affairs was constantly embittered by the nefarious activities of mushroom companies that had the object of cheating unwary public and who cashed in on the enthusiasm shown by the deposit subscribing public. Since a legal was absent depositors began to get defrauded frequently. What was even more worrisome than the actions of these defrauding companies were the defaults of the genuine companies. These companies could not honor their commitments to pay interest or repay deposits accepted by them due to financial crunches. A Cause for Control In light of such a situation the RBI stepped in and assumed powers to regulate acceptance of deposits by non-banking institutions through an amendment to the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934. RBI followed up the assumption of these powers by issuing directives regulating the acceptance of deposits by NonBanking Financial, Non-Banking Non-Financial, Miscellaneous Non-Banking and Residuary Non-Banking companies.2 All this while the principle Act governing the activities of companies i.e. the Companies Act, 1956 remained devoid of any provision affecting the legal regime 1 2 Raghuraman, G., “ Company Deposits: Protection to Depositors”, (1990) 1 Comp LJ 109. Ibid; Also see Majumdar, A.K., “Acceptance of Deposits by Companies”, 50 Taxman 254 (1990). 5 of company deposits. This anomaly was rectified in 1974 by an amendment, which inserted s.58A which in turn mandated the making of certain disclosures by way of an advertisement which every company seeking deposits was expected to issue. Importantly, the section empowered the Central Government to make rules pertaining to the manner in which companies could accept deposits.3 In 1975 the Central Government in exercise of it’s power under s.58A introduced the Companies (Acceptance of Deposit) Rules, 1975. The Sachar Committee Recomendations The Sachar Committee which went into the simplification of the Companies and MRTP Acts had looked into the various aspects of protection to deposit holders in its report in 1978. They explained that though depositors were themselves undertaking a risk by going in for unsecured deposits which came with higher rates of interest it was still the duty of the legislators to educate and caution the depositors about such risk. The Sachar Committee also recommended that some effective be made available to aggrieved creditors.4 Thus though s.58A and the rules of 1975 ushered in an operative legal regime for company deposits they left a fair bit to be desired in terms of dealing with the consequences of default in repayment and in payment of interest. Successive amendments in 1988 and in 1996 have remedied the situation to an extent by invoking the control of the Company Law Board (as per the advice of the Sachar Committee way back in 1978). 3 4 The Companies (Acceptance of Deposit) Rules, 1975 are a outcome of such an exercise of power. Chandratre, K.R., Handbook on Company Deposits, Bharat Law House: New Delhi, 1994, p.4, 5. 6 Research Methodology In this research paper the researcher has to strike a balance between the procedural formalities and substantive intricacies of the legal regime of company deposits. The law of company deposits spans not just one of the most exhaustive sections in the Companies Act, 1956 in the shape of s.58A but also an entire set of rules in the shape of the Companies (Acceptance of Deposit) Rules,1975. The area is typically riddled with procedural formalities incorporated to safeguard the interests of the public. There are substantial questions relating to the nature of deposits, credit-rating trends and judicial attitudes towards constitutional challenges to s.58A but an analysis of the regime entails an illustration of the procedure. Prior literature on this subject is restricted to reasons for the imposition of the regime and instructions on how to go about the process of inviting deposits. As a recourse a fair bit of statute analysis had to be undertaken by the researcher and for a few issues reliance was placed purely on leading case law. The method of research combined statute and case analysis wherever possible with descriptive summarisation of necessary procedure to give the reader an idea of the procedural depth of the subject. In the opinion of the author this subject topic would make a suitable research topic for a student undertaking a seminar. The paper adopts a three-pronged approach; 1) What qualifies as a public deposit for the purposes of regulation? 2) What are the procedural formalities involved in inviting and accepting deposits? 3) What are the main areas of contention and development? The manner of footnoting is standard and uniformly followed. 7 What Constitutes a Company Deposit What is a Deposit? Section 58A offers no assistance in proffering an exhaustive definition of the term “deposit”. According to the explanation deposit means any amount of money borrowed by a company (but exclusive of exempt categories for the purposes of s.58A). Rule 2(c) of the corresponding rules define a “depositor” as including any person who has given a loan to a company. The best statutory definition is proffered by the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934 in which s.45-I(bb) states, “deposit shall include, and shall be deemed always to have included, any money received by a non-banking institution by way of deposit, or loan or in any other form, but shall not include amounts raised, by way of share capital, or contributed as capital by partners of the firm.”5 It is an action that establishes the relationship of debtor and creditor or borrower and lender.6 Constitution of “Public” Since the regulations under s.58A of the Companies Act apply to invitations to the public to deposit the scope of the expression “public” assumes critical importance. The contentious question here concerns the status of the employees of the company. The Department of Company Affairs vide clarification No,8/48 of 1984 stated that; 1) Public included a section of the public as well; 2) Neither sub-section (1) nor sub-section (2) of s.58A excluded from it’s ambit the employees of the company. Thus employees are to be taken as “public”. Since s.58A is attracted only if the invitation or acceptance is from the public deposits accepted from friends, relatives and associates are not affected (employee excluded). In such application upon request from the prospective depositor it must be made clear that the form cannot be made available to a third person because then it would enter the public sphere for the purposes of the law. 5 Supra n.4 at 5. Shanbhogue, K.V. and Ganesan, K., Guide to Company Deposits and Commercial Paper, 3rd Edn., Wadhwa: Nagpur, 1990, p.59. 6 8 Loans and Deposits The explanation to Section 58A of the Companies Act supplies a wide connotation to the term “deposit”. It states that the term “deposit” means any deposit of money with, and includes any amount borrowed by a company. Prima facie, the explanation suggests that loans are also deposits within the meaning of the Act. This conclusion seems to be reinforced by the definition of “depositor” under Section2 (c) of the Acceptance of Deposits Rules. Depositor is defined to include any person who has given a loan to the company.7 Thus we are left with a familiar but awkward situation where the relevant statutes do not offer any help in drawing a distinction. The distinction is to be found in the judgements of the Apex Court, which has repeatedly pointed out that the distinction is fundamental. In Annamalai v. Veerappa8, the Supreme Court observed that although, in a particular case, the term “loan” may include “deposits”, every loan is not a deposit. It indicated, in the course of drawing the distinction, that; The person making the deposit has no right to call back the deposit; The deposit does not become a debt until the period for which the money is deposited expires and As a consequence the creditor has no right to recover the money before the deposit period concludes. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that whether a transaction is a loan or a deposit will depend on the surrounding circumstances, the relationship and character of the transaction and the manner in which the parties treated the transaction.9 However despite this three-point distinction it cannot be concluded that there exists no confusion since the two overlap considerably. 7 Chakraborti, A M, Taxman's Corporate Law, Taxman Allied Services (P) Ltd.: New Delhi, 1995, p.227. AIR 1956 SC 12 9 Ram Janki Devi v. Juggilal Kamlapat, AIR 1971 SC 2551; Durga Prasad Mandelia v. Registrar, (1987) 61 Comp. Cas 479; cited from Chandratre, K.R., Handbook on Company Deposits, Bharat Law House: New Delhi, 1994, p.7. 8 9 Debentures and Deposits Thought the definition of “debenture” contained in clause (12) of section 2 is inclusive it does not throw much light on the true nature of a debenture it clearly categorizes a debenture as a kind of security. A debenture can be said to an issue of security by a company for being put into the money market in order that they remain transferable.10 A deposit differs from a deposit in certain fundamental respects; A deposit receipt is not a security; A deposit is not issued or put into the money market; A debenture is transferable (secs.118, 111,112 and 113) while a deposit is not; A debenture can be perpetual (s.120) while the very nature of deposits implies a specific period; There are also several statutory differences that set apart debenture from loans.11 Secured Deposits Normally deposits are unsecured but there is no bar under the rules to securing of deposits though it is interesting to note that it was this unsecured nature of deposits that spurred the imposition of the legal regime in the 1960s. However, as per s.125 the charge created by securing the deposits has to be registered with the Registrar of Companies. Where security is to be given, a mention must be made in the advertisement seeking deposits.12 Since under the Capital Issues (Control) Act, 194713 all issue 10 Ittiavira Thomas v. Joseph Tile Works Ltd., AIR 1957 TLC 6. The Companies Act permits the re-issue of redeemable debentures (s.121) while a deposit can only be renewed in accordance with rules made by the Central Government (s.58A (1)). The Act requires the maintenance of register of debenture holders (s.152), issue of debenture certificates (s.113) and the calling of meetings of debenture holder (s.170). None of these requirements apply to deposits. 12 A specimen statement of such a security notification is as follows; “ The deposits are secured. The security is charge by way of hypothecation of the current assets of the company. This charge is subject to the charges already created or which may hereafter be created in favour of banks and financial institution. The charge has been registered with the Registrar of Companies,……..pursuant to the provisions of Section 125 of the Companies Act, 1956.” Obtained from Shabhogue, K.V., op.cit.. 11 13 10 of capital involving securities has to be made with the consent of the Controller of Capital Issues the same has to be obtained in the case of the secured deposits. 11 Deposits Exempt from the Regulatory Framework For the purposes of the Rules certain categories of borrowings are excluded. Therefore, none of the restrictions specified in the rules specified in the Rules (limitation on amount of deposits, terms of deposit, interest ceiling etc.) are applicable to these exempt deposits. Therefore exempt deposits can be accepted freely as usual.14 The following deposits are exempt;15 Amounts Received from the Government16 Amounts Received from Foreign Sources17 Loans from Banks18 Loans from Institutions19 Deposits by Wholly Owned Government Financial Companies Notified Financial Companies/ Public Financial Institutions Amount Received from another Company (Inter-Company Deposits)20 Amount Received from Employee by way of Security Deposit21 Amount Received from Agents22 Advances against Orders (for supply of goods etc.)23 Subscriptions to Securities24 Calls in Advance of Shares25 Trust Moneys26 Money in Transit27 Amount Received from Directors28 Shareholders Money29 Secured Bonds or Debentures30 14 They, are still obviously subject to other restrictions such as articles of association and memorandum of association. 15 Supra n.6 at 78-85. 16 Rule 2(b)(i). 17 Rule 2(b)(i). 18 Rule 2(b)(ii). 19 Rule 2(b)(iii). 20 Rule 2(b)(iv). 21 Rule 2(b)(v). 22 Rule 2(b)(vi). 23 Rule 2(b)(vi). 24 Rule 2(b)(vii). 25 Rule 2(b)(vii). 26 Rule 2(b)(viii). 27 Rule 2(b)(viii). 28 Rule 2(b)(ix). 29 Rule 2(b)(ix). 12 Convertible Bonds or Debentures31 Promoters Unsecured Loans32 Earlier Deposits33 Status of Unclaimed Deposits Deposits that have matured but have not been claimed by the depositors are known as “unclaimed deposits.” The importance of qualifying the status of these deposits arises in the context of the determination of the ceiling (imposed by the rules) on receivings by way of deposits. If the unclaimed deposits are X and the ceiling is 5X then the company can further accept only 4X (i.e. 5X - X). However if the unclaimed deposits can be treated as monies held in trust then they are exempt for the purpose of the rules and can be discounted in the ascertainment of the ceiling. The Company Law Board has issued such a clarification34, which has sorted out the dispute in a manner unfavourable to companies holding unclaimed deposits. According to the circular both unclaimed and unpaid deposits are to be taken into account for computing the ceiling on deposit holdings. Thus having regard to the clarification it is advisable that companies in their accounts show unclaimed matured deposits under Fixed Deposits. 30 Rule 2(b)(x). Rule 2(b)(x). 32 Rule 2(b)(xi). 33 Explanation in Rule 2(b). 34 Circular No. 8/13 of 1986 c.f. Supra n.6 at 92. 31 13 Invitation of Deposits Before a company allows or invites any other person to invite deposits, on its behalf, it must issue an advertisement including therein a statement illustrative of the financial position of the company and other particulars prescribed under the rules vide Section 58A(2). Of course such requirement need not be fulfilled by “exempt” deposits. The advertisement must contain a reference to the condition subject to which deposits shall be accepted and the date on which it was approved by the directors (as per rule 4(2)) and the particulars to be mandatorily included are: Name of the Company Date of Incorporation of the Company The Business carried on by the Company Brief Particulars of the management of the Company Details of Directors of the Company Profit Accounts for three financial years Dividends declared in respect of the three aforesaid years Summarised financial position35 Ceiling on amounts that may be raised by deposits and present deposit holdings Declaration of no overdue deposits or in the case of overdue deposits; indication of the same Declaration of compliance with regulations.36 It is important to note that the above list of what can be included in the advertisement under S.58A. It is merely indicative of the mandatory requirements. A company may include any other statement, not amounting to mis-statement under S.58B, which inspires confidence in the creditworthiness and investor-friendliness of the advertising company. It is for this purpose that such as CRISIL ratings are frequently exercised. Besides the above listed mandatory requirements the company must also include information 35 36 Rule 4(2)(h) of the Rules. Rule 4(2) of the Rules. 14 corresponding to the type of deposit scheme proffered and any statutorily specified terms thereof.37 Since the provisions of the Act relating to prospectus are applicable so far as they may be to 58A advertisements the scope of the extra information that may be given is roughly set out.38 37 For instance in the case of a secured deposit a statement expressing that intention must be made. Such a statement assumes mandatory nature. 38 S.58B of the Companies Act, 1956. 15 Incorporation of Credit-Rating in Deposit Advertisements With a view to create confidence in the minds of prospective depositors ensuring better response to offers of deposits companies now seek credit ratings and place the same in the advertisements seeking deposits.39 The credit rating must be received from an agency recognized by the central government. At present there are three credit-rating agencies in India, they being, Credit Rating Information Services Ltd. (CRISIL) Investment Information and Credit Rating Agency of India (ICRA) Credit Analysis and Research Ltd. (CARE) Ratings are based on objective analysis of information, as also clarifications obtained from the concerned company and other sources. CRISIL Ratings CRISIL’s prime objective is to rate debt obligations of Indian companies. It’s ratings provide a guide to the investors as to the risk of timely payment of interest and principal on a particular debt instrument. Besides rating deposit schemes CRISIL also rates debentures, short-term instruments and preference shares. A CRISIL rating relates specifically to a particular debt instrument and is not a rating for the company as a whole. The rating is not a recommendation to invest or not to invest but merely to help the prospective investor make the correct investment choice. CRISIL adopts a two-pronged approach in considering the credit-worthiness of the borrowing company; Business Analysis Financial Analysis In it’s Business Analysis it considers; Industry Risk (nature and business of competition; key success factors; demand supply position; structure of industry; Government policies) Vijia Kumar, N., “Company Deposits – From window-dressing to credit rating”, 5 Sebi & Corporate Laws 73 (1995). 39 16 Market Position of the Company within the Industry (market share; competitive advantages; selling and distribution arrangements; product and customer diversity) Operating Efficiency of the Company (location advantages; labour relationships; cost structure and manufacturing efficiency as compared to those of competitors) Legal Position (terms of prospectus, trustees and their responsibilities; systems for timely payment and for protection against forgery/fraud) In it’s Financial Analysis CRISIL considers; Accounting Quality (misstatement of profits; auditors’ qualifications; methods of income recognition; inventory valuation and depreciation policies; off balance sheet liabilities) Earnings Protection (sources of future earnings growth; profitability ratios; earnings in relation to fixed income charges) Adequacy of Cash Flows (in relation to debt and fixed and working capital needs; variability of future cash flows; capital spending flexibility; working capital management) Financial Flexibility (alternative financing plans in times of stress; ability to raise funds; ARP (Asset Reemployment Potential)) The above-mentioned list is not exhaustive of the factors considered by CRISIL.40 Rating symbols for deposit schemes are as follows41; Rating Indications regarding Degree of Safety FAAA Degree of Safety regarding timely payment of interest and principal is very strong FAA Degree of Safety regarding timely payment of interest and principal is strong. However relatively weaker than FAAA rating holders FA Degree of Safety regarding timely payment of interest and principal is satisfactory. Changes in circumstances can affect these issues more than those in higher rated categories FB Degree of Safety regarding timely payment of interest and principal is inadequate. Issues are susceptible default 40 41 Other factors to be considered depends on type of company. Obtained from Supra n.6 at 96. 17 Finalisation of Matters relating to Acceptance of Deposits Limits on Amounts Invited for Acceptance The various types of deposits are divided into two categories, which are subject to different quantitative limitations.42 The table below represents the categorisation;43 Category and Accorded Limitations Category I Deposits The limit is 10 % of the aggregate of the paid-up capital and free reserves44 as reduced by accumulated balance of loss, balance of deferred revenue expenditure and other intangible assets Category II Deposits 25% of the aggregate of the paid-up capital and free reserves as reduced by accumulated balance of loss, balance of deferred revenue expenditure and other intangible assets 42 Types of Deposits Deposits against unsecured debentures Deposits from Shareholders Deposits guaranteed by persons who were directors, managing agents or secretaries of company at the time of the guarantee Short-term deposits of 3 months or more but less than 6 months of the above categories up to 10% but within 15%45 All Other Deposits Rule 3 See supra n.6 at 99. 44 See next sub-chapter on how this is arrived at. 45 Rule 3(1)(2); As from April 1 st 1981, only the following categories of short term deposits can be accepted; (1) deposits against unsecured creditors; (2) deposits from shareholders; 43 18 Calculation of Paid-up Capital and Free Reserves The aggregate of paid-up capital and free reserves (for the purposes of calculating the ceiling) is arrived at as per the latest audited balance sheet. 46 Audited balance sheet is one which has been audited by the statutory auditors for the purpose of laying down before the annual general meeting and on which the auditors should have given a report in terms of s.227 of the Companies Act. 47 Free reserves means reserves of funds not set-aside for any specific purpose.48 The FERA Factor While finalizing the terms, the conditions, if any, imposed by the RBI under s.26(7) of the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act, 1973 on certain companies should be kept in mind and incorporated in the terms and conditions governing the acceptance. Section 26(7) mandates that no company (other than a banking company) in which the non-resident interest49 is more than forty percent shall borrow money from a person resident in India, or accept a deposit of money from such person without the permission of the RBI. Penalty for Accepting Deposits in Excess of Limits Acceptance of deposits beyond prescribed limits is an offence by way of Rule 3(ii) and Rule 11 of the Companies Acceptance of Deposits Rules, 1975. The entire amount borrowed by a company in excess of the permitted limits and treated as deposits under Rule 2 (b)(ix) would be repayable within 30 days with interest at the market rate subject to a ceiling envisaged in the rules.50 (3) deposits guaranteed by a director of the company or by it’s managing agent at the relevant time. 46 Explanation to Rule 3. 47 Supra n.6 at 99. 48 The term free reserves is defined under s.373 explanation (b) as being “those reserves which as per the latest audited balance sheet of the company, are free for distribution as dividend and shall include balance to the credit of securities premium account but shall not include share application money.” 49 For the purpose of this section non-resident interest means participation in the share capital or entitlement to the distributable profits of a company by any individual or company resident outside India or any company not incorporated under any law in force in India or any branch of such company whether resident outside India or not. 50 Vijay Kumar Gupta v. Eagle Paint & Pigment Industries P. Ltd., (1997) 13 SCL 179 (CLB). 19 Payment of Interest Interest is normally paid annually or half-yearly. It may be paid on specific dates or on the expiry of some period. Payment on fixed dates is usually preferred because it facilitates processing and control. Default in Payment of Interest When a company defaults in the payment of interest, there is no contravention of the Act or the Rules but a cause of action will arise because the default would amount to a breach of contract. The depositor may file a civil suit for the amount due and damages, if any.51 Under s.434 of the Companies Act it is provided that a company will be deemed to be unable to pay it’s debts if the creditor, to whom an amount of not less than 500 rupees is due from the company, serves a notice on the company. In light of the remedies presently available it would seem reasonable for the Rules to incorporate a remedial provision with regard to non-payment of interest. 51 Supra n.6 at 193. 20 Remedies for Refund of Deposits Company Law Board Prior to 1988 the legal regime of company deposits was devoid of any effective remedial provisions for the aid of aggrieved depositors. The Companies (Amendment) Act, 1988 remedied that situation by introducing sub-section (9) to s.58A. Vide the effect of these recent amendments the Company Law Board is now equipped with suo moto powers with regard to ordering the repayment of deposits.52 Sub-section (9) of s.58A provides that where a company has failed to repay any deposit or part thereof in accordance with the terms and conditions of such deposit, the Company Law Board (CLB) may (if it is satisfied, either on it’s own motion [suo moto] or on the application of the depositor, that it is necessary to do so to safeguard the interests of the company, the depositors or in the public interest) direct, by order, the company to make repayment of such deposit or part thereof forthwith or within such time and subject to such conditions as may be specified in the order. In Modi Carpets Ltd.53 it was held that the CLB, on it’s own motion, can call details of all the outstanding deposits of the company and issue directions for their directions for their discharge in the order of the maturity dates together with the respective simple interest. As regards Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFC’s) the CLB has been empowered by the insertion of s.45QA in the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1997 to order repayment of deposits. This action can be taken suo moto or on the application of the depositor. Writ Jurisdiction In State of West Bengal v. Union of India54, the Calcutta High Court allowed a writ petition filed in the interest of depositors by way of public interest litigation and observed that the mere existence of an alternative remedy did not deter effective writ jurisdiction. It said that since the remedy must not be merely alternative but also efficacious an “alternative remedy” defeating writ jurisdiction cannot be said to be there in the Companies Act which incorporates insufficient remedies. 52 Supra n.7 at 74 [1991] 6 CLA 152 (CLB). 54 AIR 1996 Cal 181. 53 21 Rule 3-A of the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Act, 1975: A Permanent Bone of Contention In Modi Spinning & Weaving Mills Company Ltd. v. Union of India55, the validity of rule 3-A was first questioned. The matter was re-agitated in Ahmedabad Manufacturing and Calico Printing Co. Ltd. v. Union of India56 and then finally settled by the Supreme Court in Delhi Cloth and General Mills Co. Ltd. v. Union of India57. Since the issues were common they are addressed together. The suspect rule provides that every company accepting deposits should maintain some liquid assets by depositing or investing [10%]58 of the amount collected by way of public deposits in a bank or in securities of the Central Government. The contentions of the petitioners were twofold; 1. Rule 3A did not relate to invitation or acceptance of deposits but affected their utilisation and thus was ultra vires the power under s.58A 2. Rule 3A was arbitrary and injured the very purpose of taking deposits i.e. making available funds and thus it was unreasonable and hence struck down by Art.14 of the Constitution. In response to the first question the Supreme Court held that Rule 3A cannot be said to have no nexus to the objects sought to be achieved by s.58A since the rule extends protection to the depositor in accordance with the purpose of s.58A. It said that s.58A was designed to introduce some measure of control over nonbanking companies and rule 3A was one such condition that made would make available a small portion of the deposit available to the depositor (if the company failed in it’s obligation). It said that an implicit part of “acceptance” was the condition that repayment of the deposit would be made and made at the time of the maturity. Thus, it could not be said that rule 3A bore no relation to the theme of s.58a and was ultra vires the same. 55 AIR 1979 All. 221. (1983) 53 Comp. Cas. 904. 57 (1983) 54 Comp. Cas. 674. 58 Now the figure is 15% vide the Companies (Acceptance of Deposits) Amendment Rules, 1992. 56 22 In response to the second contention the Supreme Court said that requiring the company to invest or deposit 10% of it’s deposits maturing in a year with prescribed institutions did not amount to a deprivation of funds of the company. The 10% amount is an earmarked fund necessary to fulfil the protective purpose of s.58A of the Act. Thus the validity of rule 3A stands judicially affirmed and re-affirmed. 23 Commercial Papers : A Practice in Vogue The commercial paper (CP) is an unsecured promissory note issued by corporate borrowers to meet their short term requirement of funds. Although it is new to the Indian Money Market the instrument is most likely to play an important role in the generation of funds. Commercial paper borrowings are deposits exempt from the purview of s.58A and thus the corresponding rules.59 By exempting CPs from the purview of s.58A, raising of funds by way of commercial papers is subject to regulation by the directions of the Reserve Bank of India. All Indian companies wishing to raise deposits by issue of commercial paper have to comply with the Non-Banking Companies (Acceptance of Deposits through Commercial Paper) Directions, 1989. By a general permission the RBI has permitted Indian Companies to raise funds from NRIs by issue of untransferable commercial papers.60 59 60 Nathan, Joseph, “Commercial Papers: Salient Feature and Tax Implications”, 51 Taxmann 170 (1990). Notification No.FERA 85/89-RB of 9th October, 1989. 24 In Conclusion The Role of the Company Law Board In Pure Drinks (New Delhi) Ltd, Patiala61, the Company Law Board declared that there was no merit in the contention that the CLB had no power to frame a scheme for payment to depositors and that it could pass orders only on individual applications.62 By virtue of the amendment in 1988 the CLB has powers to act suo moto or on application of depositors. Earlier, the power of the CLB under sub-section (9) was restricted in respect of non-banking non-financial companies but now as a consequence of the insertion of s.45QA in the RBI Act, 1934 (vide amendment in 1997) the CLB can also check NBFCs. All the above developments are indicative of the growing power of the CLB in controlling the financial activities of these companies. The last 10 years have seen the CLB’s functions diversify to the extent of checking what are purely financial activities of companies. Provisions in the pending New Companies Bill The Companies Bill, 1993 contains a salutary provision in clause 444 – a. enabling depositors to appoint a nominee who may claim the amount in the event of the death of the depositor; b. debarring a company which has failed to repay any deposit or any part thereof or interest thereon from accepting further deposits till the default is made good; and c. making it mandatory that a credit rating certificate shall be obtained by the company from a credit rating agency recognised by the Central Government in this behalf. Clause (b) is greatly appreciated because it places at par defaults in payment of interest and payment of deposits. By constantly according the two different gravity the legislature has weaned away the rights of the person wrongfully deprived of his interest. Now the company faces the same consequence for both. 61 (1992) 73 Comp Cas 190 (CLB). 25 Clause (c) is an excellent improvement because it allows the public to evaluate the credit worthiness of a company by using a standard benchmark which would over a period of time become easily identifiable to the public.63 However, since the transition from a Bill to an Act is as uncertain as it gets all we can do is cross our fingers. Chandrachud, Y.V. and Dugar, S.M., Ramaiya’s Companies Act, 14th Edn., Wadhwa: Nagpur, 1998, p.529. 63 See chapter on Credit Ratings. 62 26 BIBLIOGRAPHY Articles Majumdar, A.K., “Acceptance of Deposits by Companies”, 50 Taxman 254 (1990). Nathan, Joseph, “Commercial Paper – Salient Features and Tax Implications”, 51 Taxman 170 (1990). Raghuraman, G., “ Company Deposits: Protection to Depositors”, (1990) 1 Comp LJ 109. Sahai, R.N., “Invitation and Accepting of Public Deposits by a Company”, 18 Corporate Law Advisor 78 (1995). Vazifdar, N.J.N., “Acceptance of Deposits”, Chartered Secretary, September 1997. Vijia Kumar, N., “Company Deposits – From window-dressing to credit rating”, 5 Sebi & Corporate Laws 73 (1995). Books Chakraborti, A M, Taxman's Corporate Law, Taxman Allied Services (P) Ltd.: New Delhi, 1995. Chandratre, K.R., Handbook on Company Deposits, Bharat Law House: New Delhi, 1994. Farrar, J H et al, Farrar's Company Law, 3rd Edn., Butterworths: London, 1991. Pennington, R, Company Law, 7th Edn., Butterworths: London, 1995. Ramaiya, A, Guide to Companies Act, 14th Edn., Wadhwa and Co.: Wadhwa, 1998. Shanbhogue, K.V. and Ganesan, K., Guide to Company Deposits and Commercial Paper, 3rd Edn., Wadhwa: Nagpur, 1990. Singh, Avtar, Company Law, 12th Edn., Eastern Book Company: Lucknow, 1999. 27 Miscellaneous Sachar Committee Report, 1978. Miscellaneous Non-Banking Companies (Reserve Bank) Directions, 1973. Non-Banking Financial Companies (Reserve Bank) Directions, 1966. Non-Banking Non-Financial Companies (Reserve Bank) Directions, 1966. The Companies (Acceptance of Deposit) Rules, 1975. The Companies Act, 1956. The Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.