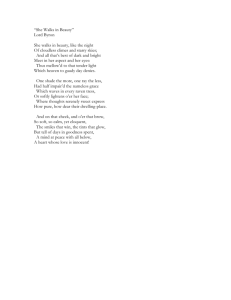

rehabilitating beauty

advertisement