Mark Burnett, School of English

advertisement

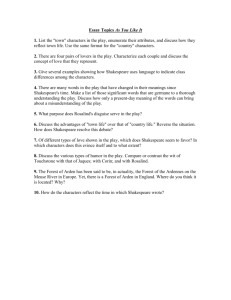

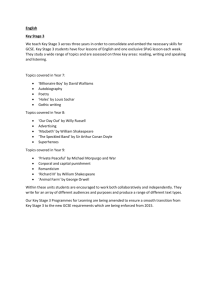

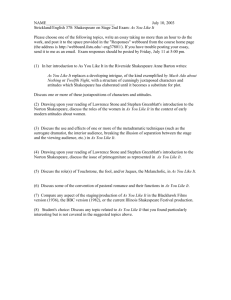

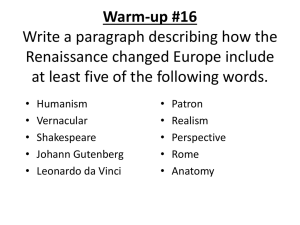

APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 QUB TEACHING AWARDS APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 (Open to individual academic and learning support colleagues who have been teaching/supporting learning within higher education for 5 or more years) Contact details Name (including title): Professor School/Department: Mark Thornton Burnett English 1 APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 1. CONTEXT FOR THE APPLICATION (300 words maximum) Please provide a context for your application. This should consist of an introductory statement about your contribution to learning and teaching/learning support to date. Examples of the information you might include are; the subject you teach or the area of learning support you work in, the type of learning and teaching/learning support activities you are involved in, how many learners are involved, your particular learning and teaching/learning support interests and an outline of your overall teaching/learning support philosophy? I have been teaching at QUB for 23 years and have always regarded teaching and research as inseparable. I teach at all levels of the School, including team-teaching at Stages 1 and 2 and research-led modules at Stage 3 and MA. At Stage 3, my module is among the most popular in the School and has attracted praise from a succession of external examiners. At MA level, I have pioneered a new programme, taught between QUB and UCD, which has increased module offerings and student numbers. I also take seriously my PhD supervisions, and my track-record of successful completions and job placements is exemplary. My teaching and research focus on the English Renaissance – the age of Shakespeare and Marlowe. It is a privilege to teach this period, but this also brings its own challenges. For me, these challenges must be met in a student-led learning environment which balances subject-specific knowledge with the acquisition of transferable skills. My methods for achieving this balance – in a student-led environment – will be discussed in 2a in relation to my Stage 3 module, ‘Reading Shakespeare Historically’ (which has been running, albeit in an ever-developing format, since 2000). My teaching has received excellent feedback from students and has led to invitations to disseminate my methods. I have written two best-selling textbooks (cited in 2b). More recently, in 2011, I was invited to talk about my teaching on the National Endowment for the Humanities summer institute for college and university teachers at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC. I find opportunities like these are a wonderful way of reflecting on my teaching and the ways in which it has continued to develop. Hence, I was pleased to contribute a chapter on teaching, entitled ‘Teaching Shakespeare Historically’, in the Palgrave collection, Teaching the Early Modern Period (2011). 2. DISCUSSION You should illustrate your discussion throughout with reference to specific learning and teaching/learning support activities. You should also provide examples of the influence of learner feedback on your learning and teaching/learning support practice. (a) Promoting and enhancing the learners’ experience (1000 words maximum) My Stage 3 research-led module, ‘Reading Shakespeare Historically’, is challenging in several ways. Firstly, ‘Shakespeare’ and ‘History’ are equally prioritized, which means that students have to get to grips with a wide range of unfamiliar materials (including early printed pamphlets and ballads) and learn how to relate these to a series of Shakespearean plays and poems. From the start, I flag up three elements of critical engagement – textual (how to read a play), historical (how to deploy historical evidence) and theoretical (how to be self-conscious regarding approach). Because I believe that students learn best by doing, I encourage a student-led method, using every opportunity to keep students active. An active learning environment is, I find, the best way in which to nurture transferable skills (in particular, critical thinking, creativity, and written and oral communication). For me, as tutor, a growing confidence is 2 APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 palpable in the classroom, while feedback highlights students’ own sense of the extent to which they have grown over the course of the semester. Given the module’s ambitions, orientation is essential. The first session centres on creating active learners. ‘What is history, and where can we find it?’ are the open questions posed as I distribute course materials. The context pack – which comprises extracts, illustrations, citations, lists of further reading, and so on – is a first port of call. I focus attention on relevant passages and, in this way, a question that frequently occurs – how, exactly, do we historicize at the level of an argument? – is confronted early on via practical examples. Important here is my stress on the fact that the context pack represents a startingpoint only. I also direct attention to areas of the library, to collections of facsimiles, to early printed book holdings and, most importantly, to Early English Books on Line (EEBO), an online resource that makes available the wealth of early modern literature and culture. This resource, in conjunction with resources available at the McClay Library, holds out infinite possibilities for contextualization, and taking full advantage of this technology has been one of the major ways in which this module has developed and been refined. One group exercise invites students to pick topics out of a hat – and then withdraw in pairs – to select a salient and stimulating EEBO example. Crucial in these activities is having students value not just the ‘what’ but also the ‘how’ of discovery. Orientation is inseparable from the assumption of certain kinds of student responsibility. At Stages 1 and 2, teaching is organized around tutorials and lectures, an arrangement that makes for a two-pronged ‘go’ at a particular text. By Stage 3, however, students are given a stand-alone seminar, with the result that time needs to be spent on easing the way into a new – and more individually-oriented – teaching situation. Encouraging responsibility is the module requirement of a seminar presentation (worth 10%) from every student. Students compose two to four pages of questions, comment and pertinent contextual ‘finds’ that are distributed, in advance, to the rest of the class. For the accompanying oral presentation, I encourage interactivity by stressing the need explicitly to engage the class. The significance of the provision of material to the other members of the class is explained as follows – each presentation represents a potential body of evidence to be taken up in later endeavours. If each student completes his/her presentation, the class will possess, by the end of the semester, a file that can be marshalled in the assessed essay. Feedback suggests that students value the ways in which individual pieces feed into a final compilation; each member of the class can shape, and have an effect on, the writing process. Students learn to appreciate that they are working not just for themselves but also for each other. The need to read according to theoretical templates is impressed upon students in the session devoted to writing skills. As well as seeing students individually, I offer a group discussion, having assembled a generalized list of the positive and less positive aspects of work submitted for formative assessment. This has the advantage of de-individuating students (everything is anonymous) while, at the same time, opening up a group dialogue and a concomitant sense of a shared enterprise. For example, in reflecting upon how we describe ‘character’ inside ‘history’, two statements might be contrasted – ‘Hal is constructed as fundamentally determined by the anxieties of his time’ and ‘Hal is worried about his family and inheritance’. Notably, the statements are presented not as wrong and right but as examples for students actively to adjudicate between. Debate introduces an element of peer-assessment into the writing process as well as alerting students to the need for due reflection as the summative writing process begins. No less important to the acquisition of skills is the sample model essay (an exercise I agreed to try rather reluctantly, at the urging of a particular student, but now value tremendously). The sample essays are anonymous, either belonging to a now-graduated student or a critic. We discuss the essay as a group, pointing out its flaws and merits. At stake, as well as the honing of critical skills, is a confrontation with authority: students are more ready to value their own contribution if they see its features reproduced elsewhere. A process of decentring is encouraged at the same time: critics, this exercise invariably 3 APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 suggests, are the prompts to further insights rather than the embodiment of an opinion that cannot be contested. Assessments (3000 word essay and class presentation) use a wide range of contexts and materials drawn from EEBO and elsewhere – sometimes not even known to me! Examiners have consistently praised the depth and density of materials enlisted, the fact that students are generally knowledgeable, the selfconsciousness of approach, and the agility and nimbleness with which students integrate text and history. One examiner describes the module as a ‘model in the field of Renaissance studies’. Most gratifyingly, there is much evidence that students carry their skills forward into the next semester’s classes and assessments. (b) Supporting colleagues and influencing support for student and/or staff learning (350 words maximum) I have always participated actively in education strategy and, at some point, have held most educationrelated posts. Putting research and teaching on an equal footing has been something of a mission – at the time of application, I am both Stage One Convenor and Director of Research. In the first role, I oversee all Stage One teaching offerings, liaise with teaching assistants, facilitate SSCC discussion and moderate examinations, ensuring that staff and students are provided with appropriate support. I hope that my enthusiasm for doing this job alongside the School’s key research post has demonstrated that both roles are important. Indeed, the positions complement each other, particularly with respect to nationallydefined ‘quality’ benchmarks. I regularly convene at Stages 1 and 2 and value a reflective practice in my team. While Stage One Convenor, I held review meetings during which I would distribute examples of graded essays and models for tutorial work. More generally, I mentor younger colleagues via my membership of probation committees and a practical pedagogical involvement in the development of PhD students. With PhD students, alongside underscoring the relevant research goals, I aim to produce a cohort of teacher-scholars eminently equipped in terms of the academic marketplace. More broadly, I am a passionate proponent of the peer review system for teaching in the School. I believe that a continued engagement with national pedagogical practice is crucially instructive. Through my external examining roles (Birmingham, Exeter, Reading and Warwick) I have taken to other institutions examples of QUB best practice. At Reading, I promoted the usefulness of the ‘masterclass’ as an aid to develop undergraduates’ oral skills; at Exeter, I argued for a more sustained use of EEBO as an instrument for encouraging enquiry. On the international stage, as well as engaging colleagues on pedagogy in India and the US (see 2c), I have produced two textbooks. Reconceiving the Renaissance (OUP, 2005) is organized around innovative ways of teaching the Renaissance to undergraduates and graduates, while my edition of The Complete Plays of Christopher Marlowe (Everyman, 1999) makes the plays accessible for an undergraduate audience. Both books have been widely adopted. (c) Ongoing professional development (350 words maximum) 4 APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 It is impossible, of course, to reflect on the practice of others, and to share one’s own good practice, without learning and developing oneself. Two practical examples – in my School, a recent peer review session made me aware of mutually-held teaching interests in Indian film and literature, which have generated, in turn, successful student applications to the University of Hyderabad/QUB exchange scheme and my proposal for a formal link with St Stephen’s College, Delhi. Similarly, the QUB/UCD Renaissance MA programme has stimulated me to be aware of the benefits that accrue to students when they are able to embrace possibilities for a widening of module access and experience a team teaching approach which extends beyond the borders of one’s own institution. More generally, during periods of external examining, I have learned more about levels of student work, contact hours, module resources, feedback and the double-dissertation as a platform for MA study, and have adjusted my own pedagogy in response. Within and beyond QUB, I pursue training opportunities. I attend teaching workshops at conferences and found a Leadership Foundation course illuminating in terms of how best to inspire colleagues to take on new challenges and work as a team. I feel it is vital keep abreast of new pedagogical materials. For example, the online journal from the British Shakespeare Association, Teaching Shakespeare – which highlights contributions not only from university lecturers but also from school teachers and theatre practitioners – has made me realize that I have much to learn from creative artists in the field. While participating in the Folger Shakespeare Library educational and outreach programme, I ensured that I attended the sessions of the other guest faculty, not least those devoted to Shakespeare and the online media environment. This has already impacted on my teaching. For example, a recent development in ‘Reading Shakespeare Historically’ is the opportunity for role play in ‘Second Life: Shakespeare’ and experimentation with costuming, casting and performance. To conclude, I may have been teaching for a long time, but I am still learning, still responsive to new strategies, and always striving to keep my pedagogy under review. 5 APPLICATION FOR SUSTAINED EXCELLENCE TEACHING AWARD 2012 Teaching Awards 2012 Criteria Profile The following are suggestions of the type of information you might wish to include in your analytical application - it is not an exhaustive list. You may also wish to draw upon educational literature within your application. Evidence of Promoting and enhancing the learners’ experience how you stimulate and inspire learners how you develop, organise and present resources how you assess learners appropriately Evidence of Supporting colleagues and influencing support for learning ways in which you contribute to the development of colleagues within your area how you contribute to institutional initiatives your contribution to regional/national/international initiatives Evidence of Ongoing professional development professional development activities undertaken how you have used these activities to review and enhance your practice how this has led to improvements for your learners. 6