Context - Liceo E. Medi

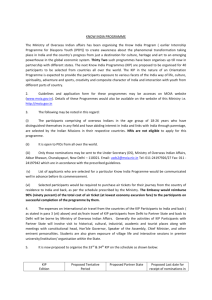

advertisement