Seizures

advertisement

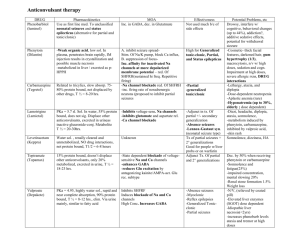

Seizures There are two kinds of seizure disorders: an isolated, nonrecurrent attack, such as may occur during a febrile illness or after head trauma, and epilepsy--a recurrent, paroxysmal disorder of cerebral function characterized by sudden, brief attacks of altered consciousness, motor activity, sensory phenomena, or inappropriate behavior caused by excessive discharge of cerebral neurons. If given a sufficient stimulus (eg, convulsant drugs, hypoxia, hypoglycemia), even the normal brain can discharge excessively, producing a seizure. In epileptics, seizures are rarely precipitated by exogenous factors, such as sound, light, and touch. Etiology and Incidence Seizures result from a focal or generalized disturbance of cortical function, which may be due to various cerebral or systemic disorders (See Table 172-1). Seizures may also occur as a withdrawal symptom after long-term use of alcohol, hypnotics, or tranquilizers. Hysterical patients occasionally simulate seizures. In many disorders, single seizures occur. However, seizures may recur at intervals for years or indefinitely, in which case epilepsy is diagnosed. Epilepsy is classified etiologically as symptomatic or idiopathic. Symptomatic indicates that a probable cause exists and a specific course of therapy to eliminate that cause may be tried. Idiopathic indicates that no obvious cause can be found. Unexplained genetic factors probably underlie most idiopathic cases. The risk of developing epilepsy is 1% from birth to age 20 yr and 3% at age 75 yr. Most persons have only one type of seizure; about 30% have two or more types. About 90% have generalized tonic-clonic seizures (alone in 60%; with other seizures in 30%). Absence seizures occur in about 25% (alone in 4%; with others in 21%). Complex partial seizures occur in 18% (alone in 6%; with others in 12%). Idiopathic epilepsy generally begins between ages 2 and 14. Seizures before age 2 are usually caused by developmental defects, birth injuries, or a metabolic disease. Those beginning after age 25 may be secondary to cerebral trauma, tumors, or cerebrovascular disease, but 50% are of unknown etiology. Symptoms and Signs Manifestations depend on the type of seizure, which may be classified as partial or generalized. In partial seizures, the excess neuronal discharge is contained within one region of the cerebral cortex. In generalized seizures, the discharge bilaterally and diffusely involves the entire cortex. Sometimes a focal lesion of one part of a hemisphere activates the entire cerebrum bilaterally so rapidly that it produces a generalized tonic-clonic seizure before a focal sign appears. Auras are sensory or psychic manifestations that immediately precede complex partial or generalized tonic-clonic seizures and represent seizure onset. A postictal state may follow a seizure (most commonly a generalized seizure) and is characterized by deep sleep, headache, confusion, and muscle soreness. Simple partial seizures consist of motor, sensory, or psychomotor phenomena without loss of consciousness. The specific phenomenon reflects the affected area of the brain (see Table 1722). In jacksonian seizures, focal motor symptoms begin in one hand and then "march" up the extremity. Other focal attacks can first affect the face area, then spread down the body to involve an arm and sometimes a leg. Some partial motor seizures begin with raising the arm and turning the head toward the moving part. Some proceed to generalized convulsions. In complex partial seizures, the patient loses contact with the surroundings for 1 to 2 min. At first, the patient may stare, perform automatic purposeless movements, utter unintelligible sounds without understanding what is said, and resist aid. Mental confusion continues another 1 or 2 min after motor components of the attack subside. These seizures may develop at any age, and structural pathology (eg, mesial temporal sclerosis, low-grade astrocytomas) should be ruled out. Complex partial seizures most commonly originate in the temporal lobe but may originate in any lobe of the brain. Complex partial seizures are not characterized by unprovoked aggressive behavior. However, if restrained during a complex partial seizure, a patient may lash out at the person restraining him, as may a patient in a postictal confused state after a generalized seizure. Between seizures, patients with temporal lobe epilepsy have a higher incidence of psychiatric disorders than does the general population; 33% may have psychologic difficulties, and 10% may have symptoms of schizophreniform or depressive psychoses. Generalized seizures cause loss of consciousness and motor function from the onset. Such attacks often have a genetic or metabolic cause. They may be primarily generalized (bilateral cerebral cortical involvement at onset) or secondarily generalized (local cortical onset with subsequent bilateral spread). Types of generalized seizures include infantile spasms and absence, tonic-clonic, atonic, and myoclonic seizures. Infantile spasms are primarily generalized seizures characterized by sudden flexion of the arms, forward flexion of the trunk, and extension of the legs. Seizures last a few seconds and are repeated many times a day. They occur only in the first 3 yr of life and then are replaced by other types of seizures. Developmental abnormalities are usually apparent. Absence seizures (formerly called petit mal) consist of brief, primarily generalized attacks manifested by a 10- to 30-sec loss of consciousness and eyelid flutterings at a rate of 3/sec, with or without loss of axial muscle tone. Affected patients do not fall or convulse; they abruptly stop activity and resume it just as abruptly after the seizure, with no postictal symptoms or even knowledge that an attack has occurred. Absence seizures are genetic and occur predominantly in children. Without treatment, such seizures are likely to occur many times a day. Seizures often occur when the patient is sitting quietly and can be precipitated by hyperventilation. They rarely occur during exercise. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures typically begin with an outcry; they continue with loss of consciousness and falling, followed by tonic, then clonic contractions of the muscles of the extremities, trunk, and head. Urinary and fecal incontinence may occur. Seizures usually last 1 to 2 min. Secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures begin with a simple partial or complex partial seizure. Atonic seizures are brief, primarily generalized seizures in children. They are characterized by complete loss of muscle tone and consciousness. The child falls or pitches to the ground, so that seizures pose the risk of serious trauma, particularly head injury. Myoclonic seizures are brief, lightning-like jerks of a limb, several limbs, or the trunk. They may be repetitive, leading to a tonic-clonic seizure. There is no loss of consciousness. Febrile seizures are associated with fever without evidence of intracranial infection. They affect about 4% of children between the ages of 3 mo and 5 yr. Benign febrile seizures are brief, solitary, and generalized tonic-clonic in form; complicated febrile seizures are either focal, last > 15 min, or recur >= 2 times in < 24 h. Overall, the occurrence of febrile seizures is associated with a 2% incidence of subsequent epilepsy; the incidence of epilepsy and the risk of recurrent febrile seizures are much greater among children with complicated febrile seizures, preexisting neurologic abnormalities, onset before age 1 yr, or a family history of epilepsy. In status epilepticus, seizures follow one another with no intervening periods of normal neurologic function. Generalized convulsive status epilepticus may be fatal. It may result from too-rapid withdrawal of anticonvulsants. Confusion may be the only manifestation of complex partial or absence status epilepticus, and an EEG may be needed to diagnose seizure activity. Epilepsia partialis continua is a rare form of focal (usually hand or face) motor seizures that recur at intervals of a few seconds or minutes for days to years at a time. In adults, it is usually due to a structural lesion, such as a stroke. In children, it is usually due to a focal cerebral cortical inflammatory process (Rasmussen's encephalitis), possibly caused by a chronic viral infection or autoimmune processes. Diagnosis Idiopathic epilepsy must be distinguished from symptomatic epilepsy. Focal seizures or focal postictal symptoms imply a focal structural lesion in the brain; generalized seizures are more likely to have a metabolic cause. In newborns, the type of seizure does not help distinguish between structural and metabolic causes. An eyewitness account of a typical seizure, the frequency of seizures, and the longest and shortest intervals between them should be recorded. A history of prior head trauma, infection, or toxic episodes must be sought and evaluated. A family history of seizures or neurologic disorders is significant. Fever and stiff neck accompanying new-onset seizures suggest meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or encephalitis. Lumbar puncture is indicated. Focal cerebral symptoms and signs accompanying seizures suggest brain tumor, cerebrovascular disease, or residual traumatic abnormalities. In an adult, even generalized seizures should stimulate a search for an unsuspected focal lesion. Appropriate studies include EEG and serum glucose, sodium, magnesium, and calcium. When the EEG or serum is focally abnormal or when seizures begin in adulthood, MRI is indicated. A lumbar puncture should be performed if infection is suspected. The EEG between seizures (interictal) in primarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures is characterized by symmetric bursts of sharp and slow, 4- to 7-Hz activity. Focal epileptiform discharges occur in secondarily generalized seizures. In absence seizures, spikes and slow waves appear at a rate of 3/sec. Interictal temporal lobe foci (spikes or slow waves) occur with complex partial seizures of temporal lobe origin. Because an EEG taken during a seizure-free interval is normal in 30% of patients, one normal EEG does not exclude epilepsy. A second EEG performed during sleep in sleep-deprived patients shows epileptiform abnormalities in half of patients whose first EEG was normal. Rarely, repeated EEGs are normal, and epilepsy may have to be diagnosed on clinical grounds. Prognosis Drug therapy completely eliminates seizures in 1/3 of patients and greatly reduces the frequency of seizures in another 1/3. About 2/3 of patients with well-controlled seizures can eventually discontinue drugs without relapse. Most patients with epilepsy become neurologically normal between seizures, although overuse of anticonvulsants can dull alertness. Progressive mental deterioration is usually related to the neurologic disease that caused the seizures. Left temporal lobe epilepsy is associated with verbal memory abnormalities; right temporal lobe epilepsy sometimes causes visual spatial memory abnormalities. The outlook is best when no brain lesion is demonstrable. Treatment General principles: Treatment aims primarily to control seizures. A causative disorder may need to be treated as well. A normal life should be encouraged. Exercise is recommended; even such sports as swimming and horseback riding can be permitted with proper safeguards. Most state licensing agencies permit automobile driving after seizures have stopped for 1 yr. Social activities should be encouraged. Alcohol intake should be minimized. Cocaine and several other illicit drugs can trigger seizures. Family members must be taught a commonsense attitude toward the patient. Overprotection should be replaced with sympathetic support that lessens feelings of inferiority and selfconsciousness and other emotional handicaps; prevention of invalidism should be emphasized. Institutional care is rarely advisable and should be reserved for severely retarded patients and for patients with seizures so frequent and violent despite drug therapy that they cannot be cared for elsewhere. During a seizure, injury should be prevented. Protecting the tongue should not be attempted because teeth may be damaged. Inserting a finger to straighten the tongue is dangerous and unnecessary. Clothing around the neck should be loosened, and a pillow placed under the head. The patient should be rolled onto his side to prevent aspiration. A responsible fellow worker may be trained to give emergency aid if the patient agrees. Causative or precipitating factors should be eliminated. Progressive structural lesions of the brain (eg, tumors, abscesses) should be sought and promptly treated. After definitive treatment of structural lesions, continued medical treatment (eg, anticonvulsants) is usually necessary. Other physical disorders (eg, systemic infections, endocrine abnormalities) should be corrected. Head injuries with skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhages, focal neurologic deficits, or amnesia cause posttraumatic epilepsy in 25 to 75% of cases. Prophylactic treatment with anticonvulsant drugs after the head injury reduces the probability of early posttraumatic seizures during the first few weeks after the injury but does not prevent the development of permanent posttraumatic epilepsy months or years later. Drug therapy: No single drug controls all types of seizures, and different drugs are required for different patients. Patients rarely require several drugs. The drug of choice for the particular type of epilepsy is started at relatively low dose and increased over about 1 wk to the standard therapeutic dose. After about 1 wk at this dose, blood levels are measured to determine whether the effective therapeutic level has been reached. If seizures continue, the daily dose is increased by small increments. If toxic blood levels or toxic symptoms develop before seizures are controlled, a second anticonvulsant is added, again guarding against toxicity. Interaction between drugs can interfere with their rate of metabolic degradation. The initial, failed anticonvulsant is then withdrawn gradually. Once seizures are controlled, the drug should be continued without interruption until at least 1 yr is seizure-free. At that time, discontinuing the drug should be considered, because about 2/3 of such patients remain seizure-free without drugs. Static encephalopathy and structural brain lesions increase the risk of relapse off medication. Patients whose attacks were initially difficult to control, those who failed a drug-free trial, and those with important social reasons for avoiding seizures should be treated indefinitely. The most effective anticonvulsants for long-term use and their doses for children and adults are given in Table 172-3. Once the drug response is known, blood levels are less useful to follow than the clinical course. Some patients have toxic symptoms at low levels; others tolerate high levels without symptoms. For generalized tonic-clonic seizures, phenytoin, carbamazepine, or valproate is the drug of choice. For adults, phenytoin can be given in divided doses or at bedtime. If seizures continue, the dose can be increased cautiously to 500 mg/day with blood level monitoring. At a higher dose, dividing the daily dose may reduce toxic symptoms. For partial seizures, treatment begins with carbamazepine, phenytoin, or valproate. If seizures persist despite high doses of these drugs, gabapentin, lamotrigine, or topiramate may be added. For absence seizures, ethosuximide orally is preferred. Valproate and clonazepam orally are effective, but tolerance to clonazepam often develops. Acetazolamide is reserved for refractory cases. Atonic seizures, myoclonic seizures, and infantile spasms are difficult to treat. Valproate is preferred, followed, if unsuccessful, by clonazepam. Ethosuximide is sometimes effective, as is acetazolamide (in dosages as for absence seizures). Phenytoin has limited effectiveness. For infantile spasms, corticosteroids for 8 to 10 wk are often effective. The optimal corticosteroid regimen is controversial. ACTH 20 to 60 U/day IM may be used. A ketogenic diet may help but is difficult to maintain. Carbamazepine may make patients with primary generalized epilepsy and multiple seizure types worse. Status epilepticus can be terminated by giving diazepam 10 to 20 mg (for adults) IV or up to 2 doses (if necessary) of lorazepam 4 mg IV. For children, IV diazepam up to 0.3 mg/kg or lorazepam up to 0.1 mg/kg is given. For adults, phenytoin 1.5 g IV may be given to prevent recurrence. Fosphenytoin, a water-soluble product, is an alternative that in equivalent doses reduces the incidence of hypotension and phlebitis. Anesthetic IV doses of phenobarbital, lorazepam, or pentobarbital may be necessary in refractory cases; in such instances, intubation and O2 therapy are required to prevent hypoxemia. In acute generalized tonic-clonic seizures due to febrile illnesses, ingestion of alcohol or other toxins, or acute metabolic disturbance, the causative condition must be treated as well as the seizures. Status epilepticus should be treated at once. If only one seizure has occurred, phenytoin should be given in full dosage (see Table 172-3) for 7 to 10 days; afterward, a decision concerning long-term therapy must be made. After a first seizure, 1/3 of patients have recurrent attacks, followed by chronic epilepsy. Anticonvulsants are of little value in preventing alcohol withdrawal seizures. Benign febrile convulsions do not require treatment because of the favorable prognosis compared with the potential toxic effects of anticonvulsants in a young child. For patients with complicated febrile seizures or other risk factors for recurrence (listed above), recurrence rates for febrile seizures can be reduced by continuous prophylactic treatment with phenobarbital 5 to 10 mg/kg/day. However, no evidence suggests that such treatment of complicated febrile seizures prevents the development of recurrent nonfebrile seizures (epilepsy). Furthermore, phenobarbital given chronically to children measurably reduces their learning capacity. Adverse effects: Possible toxic effects of anticonvulsants are listed in Table 172-3. All anticonvulsants may cause an allergic scarlatiniform or morbilliform rash. Patients receiving carbamazepine should have a CBC once a month for the first year of therapy. If the WBC or RBC count decreases significantly, the drug should be discontinued immediately. Patients receiving valproate should have liver function tests every 3 mo for 1 yr; if serum transaminases or ammonia levels increase significantly (to > 2 times the upper limit of normal), the drug should be discontinued. An increase in ammonia up to 1.5 times the upper limit of normal can be tolerated safely. When an overdose reaction occurs, the amount of drug is reduced until the reaction subsides. When more serious acute poisoning occurs, the patient is given ipecac syrup or, if obtunded, is lavaged. After emesis or lavage, activated charcoal is administered, followed by a saline cathartic (eg, magnesium citrate). The suspect drug should be discontinued, and a new anticonvulsant started simultaneously. Fetal antiepileptic drug syndrome (cleft lip, cleft palate, cardiac defects, microcephaly, growth retardation, developmental delay, abnormal facies, digital hypoplasia) occurs in 4% of the children of epileptic women who take anticonvulsants during pregnancy. Among commonly used drugs, carbamazepine appears to be the least teratogenic, but only slightly so; valproate may be the most teratogenic. Yet, because uncontrolled generalized seizures during pregnancy lead to fetal injury and death, continued treatment with anticonvulsants is generally advisable (see Ch. 249). Surgical therapy: About 10 to 20% of patients have seizures that are refractory to medical treatment. Most patients whose seizures originate from a local area of abnormal brain function improve markedly when the epileptic focus is resected. Some are completely cured. Because extensive monitoring and skilled medical-surgical teamwork are required, these patients are best managed in specialized centers. Vagus nerve stimulation: Intermittent electrical stimulation of the left vagus nerve with an implanted pacemaker-like device reduces the number of partial seizures by one third. After the device is programmed, patients can activate it with a magnet when they sense a seizure is imminent. Vagus nerve stimulation is used as an adjunct to an anticonvulsant. Adverse effects include a deepening of the voice during stimulation, cough, and hoarseness. Complications are minimal. Duration of effectiveness is not well established. Table 172-1 causes of seizures Table 172-2 partial seizures Table 172-3 drugs used in epilepsy