Medical problems in Autistic Disorders

advertisement

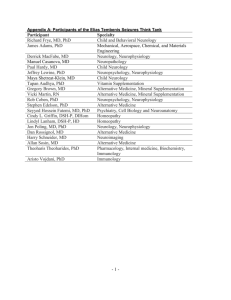

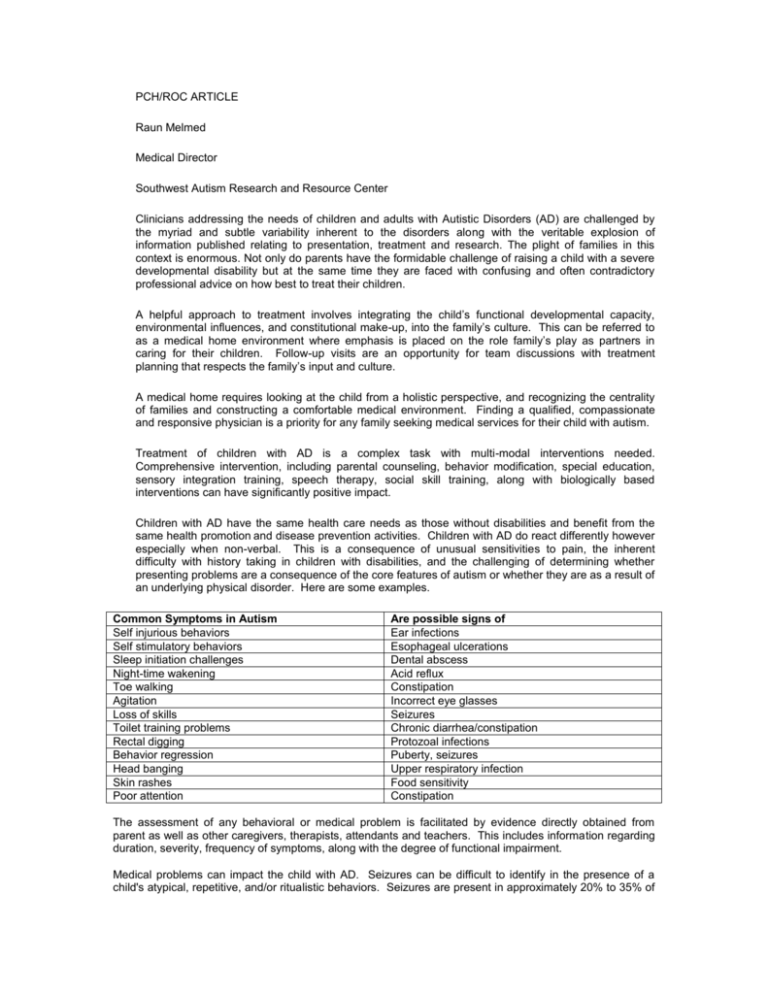

PCH/ROC ARTICLE Raun Melmed Medical Director Southwest Autism Research and Resource Center Clinicians addressing the needs of children and adults with Autistic Disorders (AD) are challenged by the myriad and subtle variability inherent to the disorders along with the veritable explosion of information published relating to presentation, treatment and research. The plight of families in this context is enormous. Not only do parents have the formidable challenge of raising a child with a severe developmental disability but at the same time they are faced with confusing and often contradictory professional advice on how best to treat their children. A helpful approach to treatment involves integrating the child’s functional developmental capacity, environmental influences, and constitutional make-up, into the family’s culture. This can be referred to as a medical home environment where emphasis is placed on the role family’s play as partners in caring for their children. Follow-up visits are an opportunity for team discussions with treatment planning that respects the family’s input and culture. A medical home requires looking at the child from a holistic perspective, and recognizing the centrality of families and constructing a comfortable medical environment. Finding a qualified, compassionate and responsive physician is a priority for any family seeking medical services for their child with autism. Treatment of children with AD is a complex task with multi-modal interventions needed. Comprehensive intervention, including parental counseling, behavior modification, special education, sensory integration training, speech therapy, social skill training, along with biologically based interventions can have significantly positive impact. Children with AD have the same health care needs as those without disabilities and benefit from the same health promotion and disease prevention activities. Children with AD do react differently however especially when non-verbal. This is a consequence of unusual sensitivities to pain, the inherent difficulty with history taking in children with disabilities, and the challenging of determining whether presenting problems are a consequence of the core features of autism or whether they are as a result of an underlying physical disorder. Here are some examples. Common Symptoms in Autism Self injurious behaviors Self stimulatory behaviors Sleep initiation challenges Night-time wakening Toe walking Agitation Loss of skills Toilet training problems Rectal digging Behavior regression Head banging Skin rashes Poor attention Are possible signs of Ear infections Esophageal ulcerations Dental abscess Acid reflux Constipation Incorrect eye glasses Seizures Chronic diarrhea/constipation Protozoal infections Puberty, seizures Upper respiratory infection Food sensitivity Constipation The assessment of any behavioral or medical problem is facilitated by evidence directly obtained from parent as well as other caregivers, therapists, attendants and teachers. This includes information regarding duration, severity, frequency of symptoms, along with the degree of functional impairment. Medical problems can impact the child with AD. Seizures can be difficult to identify in the presence of a child's atypical, repetitive, and/or ritualistic behaviors. Seizures are present in approximately 20% to 35% of children with AD and have 2 peaks of onset, the first during early childhood and the second during adolescence. Subclinical signs of seizures can be subtle and accurate history taking and observation is needed. The high incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptomatology in children with AD has been reported. At SARRC, studies have shown that 25% of the children had chronic diarrhea, and a further 25% had chronic constipation. Carbohydrate intolerance secondary to disaccharidase deficiency has been seen in 55% of children with AD with combined deficiency of disaccharidase enzymes seen in 15%. Symptoms which result from these conditions need assessment by an astute physician. Daytime irritability, inattention, or lethargy may be due to inadequate sleep. Between 50% and 80% of children with AD have abnormal sleep patterns. The value of strict sleep hygiene habits cannot be underestimated - sometimes more aggressive treatment might be warranted. All team members – including the family - should understand the indications, side effects, and limitations of any therapeutic approach. The individual with AD should be involved in the treatment process as much as possible, despite any developmental limitations. For example, every effort should be made to help the child understand the reason and purpose for taking medication and the possible side effects. The child with AD becomes a partner in the treatment process. Development is a transactional process. A wide variety of environmental interactive experiences can produce physical changes and visa versa. For these forces to be harnessed, families’ treatment choices for their children need to be understood and respected. That way, the healing capacity of health care providers can be enhanced. An open-minded and integrated approach to caring along with an awareness of the complex medical problems that children with AD face will benefit everyone.