Constitutional Law I - Black Law Students Association

advertisement

Constitutional Law I

Prof. Vermeule

By Ryan Patrick Phair

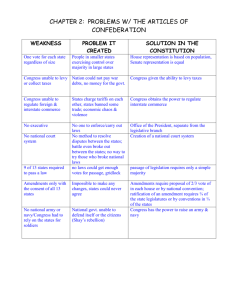

I. History of Constitutional Law

The Articles of Confederation—adopted after the Revolution to ensure some unification of the states for common

foreign and domestic problems, but state sovereignty predominated. The national government did not power to tax

and regulate commerce. There was no executive or judiciary. No Bill of Rights. There were several problems with

the Articles of Confederation:

(1) Congress unable to raise revenue to perform necessary functions. Debt piling up.

(2) A need for an executive to provide energy and resolution in domestic and foreign affairs.

(3) Interstate jealousies, producing retaliatory trade measures and inhibited flow of interstate commerce, where

pride in one’s state outweighed pride in one’s country.

(4) Individual states did not live up to commercial and other treaties, such as treaty with Britain.

However, revisionist history argues that the Articles did not generate severe general problems. The problems were

faced primarily by commercial and mercantile interests who were adversely affected by the various states and who

needed national authority for protection against states that had not fully respected rights of private property and

contract. Jensen.

a. The Antifederalist Case

Antifederalist thought drew from classical republicanism, a theory of government supported by Montesquieu and

Rousseau. Republicanism relies on civic virtue—willingness of citizens to subordinate their private interests to the

general good. Self-rule entailed selecting the values that ought to control public and private life. Public discourse

was a critical feature. Active and frequent political participation. The model was the town meeting. Government’s

first task was to ensure flourishing of the necessary public spiritedness. Since only in small communities would it be

possible to find and develop unselfishness and devotion to the public good upon which freedom depends, they

favored decentralization. Homogeneity of the people’s manners, sentiments, and interests is also necessary. For this

reason, they wanted to avoid extreme disparities in wealth, education, and power. In short, they attacked the

Constitution on several grounds.

(1) The Constitution was inconsistent with the underlying principles of republicanism.

(2) The Constitution removed the people from the political process.

(3) The Constitution created a powerful and remote national government. Representatives were a necessary evil;

however, they feared rule by remote national leaders.

(4) The Constitution emphasized commerce because it gave rise to ambition and avarice and thus to the dissolution

of communal bonds.

b. The Federalist Response

The Federalist’s reformulated republicanism by attempting to synthesize elements of traditional republicanism with

an emerging theory that welcomed rather than feared heterogeneity, and that understood the reality that self-interest

would often be a motivating force for political actors. The Federalist Papers were prominent. Although Framer’s

intent may be hard to derive from this because they were intended as propaganda to sway the ambivalent.

Madison felt the primary problem of government is controlling factions, whereas antifederalists believed corruption

was the problem, for Madison, liberty caused factions. Thus, antifederalist reform efforts of education and virtue

inculcation would not work, which Madison believed history proved. In addition, because of a republic’s ability to

control faction through diversity of interests, differences and disagreement were indispensible to government. Also, a

large republic diminishes the dangers of undue attachment to local interests. Madison favored Senate and President

more than House, long lengths of service, large election districts. Finally, Madison opposed antifederalists “right to

instruct” representatives because reps were entrusted and able to see the public good. Bicameralism intended to

ensure that some representatives were isolated from people, while others worked closely with them.

The Federalist No. 10 Madison

1. A well-constructed union tends to break and control the dangers of factions.

2. A faction is a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority, who are united and actuated by

some common interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens and the permanent interests of the community.

3. Factions may be cured in two ways:

(a) Removing the causes. There are two methods of removing causes, none of which work.

(1) Destroying the liberty that is essential to its existence. However, this remedy is worse than the disease.

(2) Giving every citizen the same interests. However, this is impossible because diversity is natural. As a

result of this inherent diversity of interest, the most common cause of faction is unequal distribution of

property. Madison recognizes that enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm to resolve the

clashes of diverse interests by ensuring the public good is served.

(b) Controlling the effects. Since the causes of faction can not be removed, controlling its effects is the only

solution.

1. If a minority faction, then the republican principle allows the majority to defeat it.

2. If a majority faction, then there are only two ways.

a) Prevent the existence of the same passion or interest in the majority at same time.

b) Render the majority unable to concert and propel schemes of oppression.

4. A democracy (small # of people who govern in person) can’t cure the mischiefs of faction.

5. A republic is different from a democracy in two ways.

(a) A republic delegates government to a small number of representatives, which filters interests through

representatives acting in the public good.

(b) A republic increases the number of people who can participate in government.

6. A large republic solves the problem of faction.

(a) With respect to the representative aspect of a republic, a large (rather than a small) republic cures the

problem of representative betrayal because there will be larger numbers of honorable representatives in the

large republic.

(b) With respect to the numbers aspect of a republic, a large republic cures the problem of representative

betrayal because more people voting makes it more difficult to deceive the people.

7. I concede that if you raise the number of representatives too much, you risk ignorance of local interests; if too

small, you risk ignorance of national interests. The Constitution, however, provides for both in that national

interests go to the national government, local interests go to the state government.

8. A large republic’s diversity of interests would reduce the risk that a common desire would be felt by sufficient

numbers of people to oppress minorities.

Madison then set up a system of checks and balances to provide a check against both factionalism and selfinterested representation. A complex system of checks is set up: national representation, bicameralism, indirect

election, distribution of powers, and federalism all operate to counteract the inevitable factional spirit.

The Federalist No. 51 (1788) Madison

The check against consolidation or usurpation of power by a government branch is giving the other branches the

constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments by other branches. The defense must be made

commensurate with the danger of attack. Ambition must counteract ambition. The government must be set up in

such a way that it is obliged to control itself. The American federalist system provides a double security against

such dangers. The different governments (federal and state) will control each other, and at the same time, each will

be controlled by itself (through checks and balances). States jealousy of federal power provides incentive to

counteract national ambition.

Judicial Review and Republicanism—Michelman argues that judicial review, in service of republican ends, provides

traces of democratic self-determination. Thus, republicanism cuts in favor of judicial activism. However, some

believe judicial restraint is consistent with republican thought because, if democratic self-determination is the end, a

powerful judiciary hardly seems to be the means.

Pluralism and Republicanism—Sullivan argues that republicanism devalues social pluralism. In light of differences

between individuals and social groups, the idea of finding a single public good often seems naïve. “Painters know

that to mix the colors of the rainbow produce mud.”

Public Choice Theory—Emerging political theory that examines the costs of mobilizing different groups to affect

the political process. Main idea is that it is harder to organize a majority than it is to organize a discrete subgroup.

Thus, Madison’s concern about majority factions may be unnecessary. See discussion infra.

The Constitution is a precommitment device (like Odysseus and the Sirens).

The three traditional reasons for why we need a written constitution—prevent factionalism, create workable plan of

government, and controlling national institutions—does not explain why the Constitution must be written. A

precommitment device does. Since the framers knew that at some future time, people’s preferences may be irrational,

we precommit to avoid such irrationality.

The Constitution precommits the people to two kinds of rules.

(1) Regulative—For example, 1st Amendment (no speech prohibition).

(2) Constitutive—enabling an activity by defining it, i.e. rules of baseball, Articles I, II, and III.

Open Issues

(1) Problem of the Dead Hand—Odysseus is binding himself, the framers bound future generations. First, where do

the framers get off binding us now? Second, at a certain point, it becomes dangerous to follow precommitments,

i.e. Congress’s power to declare war may not be fast enough. Third, circumstances may change.

(2) Who Enforces Precommitments?—Judges, executive, people through elections, states, etc.?

(3) How Do You Interpret?—There are several methods of constitutional interpretation.

(a) Textualism

(b) Original Understanding

1) Original Intent

2) Original Meaning (Federalist papers, ratification debates to derive meaning)

(c) Judicial Precedent and Common Law Constitutional Interpretation—Strauss

(d) Structuralism—Inferences from the Constitution’s general structure, i.e. we can’t interpret the Commerce

clause to say Congress can regulate everything when there are limited powers.

(e) Prudence and Morality—The problem of the precommitment that now looks like a bad idea.

Case Law—Before 1937, the Court emphasized precommitment theory. After 1937, the Court believed that the

Constitution is not a suicide pack. Since when you most want to slip your bonds, it may be when you really do want to

do that.

II. Marbury—The Supreme Court’s Power to Declare Acts of Congress Unconstitutional.

Note—Separation of Powers is purely an inference from the Articles I-III. The Massachusetts Constitution

expressly states a separation of powers principle, but the U.S. Constitution does not.

Marbury v. Madison (US 1803) Marshall

[23]

Adams appointed Marbury as a justice of the peace. The Federalist Senate confirmed the appointment on March 3,

1801. Before Marbury’s commision had been delivered, Jefferson, assuming officer several days later, told

Madison (Marshall’s replacement as SOS) not to deliver the commission. Marbury seeks a writ of mandamus. The

Court held that the Supreme Court is without power to direct the President to deliver Marbury’s commission

because the Judiciary Act’s mandamus remedy is unconstitutional.

1. Since the appointment had been made, Marbury had a right to the commission.

(a) The appointment is made when the commission has been signed by the President and the seal of the

Secretary of State had been fixed to it.

(b) In this case, Adams had signed and Marbury had affixed the seal, he just didn’t deliver it.

(c) The President may not remove Madison after the appointment because he then has a vested right in the

position.

(d) *** Note-Marshall could have ruled that delivery was required for validity, thus, disposing of the case.

2. The appointment conferred on Marbury a legal right to his office for five years.

3. The Court held that Marbury was afforded a remedy.

(a) If the U.S. is a government of laws, then there must be a remedy for violation of a vested legal right.

(b) Marshall distinguished between political acts, which are not reviewable by the courts, and acts specifically

required by law, which are reviewable.

(c) Refusal to deliver the commission is an act specifically required by law.

4. Mandamus would be a proper remedy.

(a) Marbury has no other remedy.

(b) The Secretary of State may be directed by law to do a certain act affecting the absolute rights of others.

5. However, the Court can not issue a writ of mandamus in this case.

(a) Although the Judiciary Act of 1789 allows such a writ of mandamus in the facts of this case, the Judiciary

Act of 1789 was unconstitutional so far as the mandamus provision because Article III, §2 grants the

Supreme Court original jurisdiction (as opposed to appellate jurisdiction) only in cases affecting

ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, and those in which a state is a party. This conclusion is

based on plain meaning of the statute. Affirmative words are negatives of other objects than those affirmed.

(b) According to the text, the Supreme Court would have appellate jurisdiction; however, appellate jurisdiction

corrects the proceedings in a cause already instituted. In this case, there is no case already instituted.

Indeed, mandamus must be original because it creates the cause of action.

6. If the Supreme Court identifies a conflict between a constitutional provision and a congressional statute, the

Court has the authority (and the duty) to declare the statute unconstitutional and to refuse to enforce it.

(a) The Constitution is the supreme law of the land.

(1) It would do no use setting limitations on government if they could be exceeded at will. The very

purpose of a written constitution implies is to establish a fundamental and paramount law. Counter—

Nirvana Fallacy—comparing real world alternative with a fantasy alternative.

(2) Thus, any law repugnant to the Constitution is void.

(b) The Judiciary is obligated to say what the law is.

(1) The organ that applies the law must necessarily interpret the law.

(2) If two laws are in conflict, the Court must decide which is right.

(3) The Constitution is the supreme law of the land.

(4) Thus, the Judiciary has power to declare acts of Congress unconstitutional.

(5) To deny the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review would be to say that the Court must close its

eyes to the Constitution, and see only law. This would subvert the very purpose of all written

constitutions.

(c) Since the judicial power is extended to cases “arisng under” the Constitution, it would be absurd to suggest

that the framers desired a case arising under the Constitution to be decided without reference to it.

(d) The fact that judges take an oath to support it implies that they must decide cases according to the

Constitution.

(e) The Supremacy clause states the Constitution is the supreme law of the land, not acts of Congress.

Marbury’s Critics—There are several possible criticicisms of Marbury.

(1) The categories of original and mutual jurisdiction are not mutually exclusive. The Constitution sets up a

provisional allocation, which Congress may alter. The alteration power is recognized in the Exceptions

clause. Therefore, it is constitutional for Congress to grant to the Court original jurisdiction over cases over

which it had appellate jurisdiction under the Constitutin’s provisional allocation.

(2) The Constitution defines an irreducible minimum of original jurisdiction, but permits Congress to expand

original jurisdiction if it so chooses. Note that Marbury’s reasoning has been rejected insofar as it suggests

that Congress may not give lower courts jurisdiction over cases falling within the original jurisdiction of the

Supreme Court. Illinois v. Milwaukee (1972).

(3) Look at Emanuel’s and Tribe for others.

David Currie has said that judicial review was nothing new. However, two cases he relied upon Ware and Cooper

involved a federal law-state law conflict under the Supremacy clause, not an Act of Congress-Constitution conflict.

Thus, it may yet still have been new question.

Some criticize the inference argument. Marshall’s argument that judicial review is inferred from the fact of a written

constitution is criticized because many countries have had written constitutions without having judicial review. Van

Alstyne. However, Currie argues that the framers were smart people who surely wouldn’t have put the fox as the

guardian of the henhouse. Tribe’s argument.

Some criticize the supremacy clause argument. They claim that it never says who determines whether any given

law is in fact repugnant to the Constitution. Marshall never asks this question. His question was whether a law

repugnant to the Constitution binds the courts.

Some criticize the “arising under” argument. Bickel argues that there could be cases where the court would be

required to pass on questions arising under the Constitution that do not involve legislative or executive acts, such as

military, judicial, administrative acts. Thus, Marshall’s reading is possible, but optional. Currie also criticizes this

argument by saying that the arising under clause is merely a jurisdictional provision, it need not be taken to dictate

when the Constitution must be given precedence over other laws.

Some criticize the “judge’s oath” argument. Eakin v. Raub (PA 1825) held that an oath to support the Constitution

is not peculiar to judges. It is meant as a test of one’s political principles. One must support the Constitution only as

far as that may be involved in one’s official duty. Thus, we are left again with the question of whether judicial review

is a judge’s duty.

Some structural supporters hold that the various arguments are more forceful in combination than they appear when

separated.

According to Bickel, the Framer’s did indeed contemplate judicial review.

The Federalist No. 78 Hamilton

Through judicial review, courts vindicate the will of the people (as expressed in the Constitution) against the will of

mere representatives. Hamilton is thus attempting to overcome the claim that judicial review is undemocratic.

(Countermajoritarian difficulty?)

III.

Judicial Activism vs. Judicial Restraint (Natural Law Debates)

Although modern courts do not talk about natural law, this has not always been the case.

Calder v. Bull (US 1798)

The CT legislature ordered a new trial in a will contest, setting aside a judicial decree. The Court unanimously held

that the legislature’s action did not violate the Ex Post Facto clause. Although Justice Chase and Iredell agreed on

the ex post facto issue, they disagreed over the appropriate role of natural law.

Chase—The people enacted the Constitution for certain reasons set out in the preamble. People enter into society

for certain purposes, and it is these purposes that determine the nature and terms of the social compact. A

legislative act, contrary to the social compact, is void. The general principles of reason and justice presume that the

people did not entrust a legislature with the power to act contrary to natural law. Thus, Chase upheld the CT’s

legislature’s action because it impaired no vested right and therefore was consistent with natural justice.

Iredell—A legislative act against natural justice is not void. Courts should not consider natural law for several

reasons.

(1) Indeterminacy—Judges would be regulated by no fixed standard, creating indeterminacy (some argue all law

is indeterminate).

(2) Ascertainment Difficulty—Purest men have differed on the subject.

(3) Adoption of a Written Constitution is Inconsistent with Natural Law—The American government and people

have defined with precision the objects of the legislative power and restrained its exercise within marked and

settled boundaries. Only if a legislative act violates this principle is it void.

Sherry and Grey assert that the framers intended a natural law supplement to constitutional restraints.

The desirability of natural law’s application has been debated. Some argue that recognition of natural law

principles is an indispensible protection against the potential injustice of majoritarian government. However, some

others argue that this would be intolerable in light of the basic constitutional commitment to electoral control of

elected officials.

Perry argues that electorally accountable policymaking institutions are not suited to deal with the notion that

society may morally evolve. When confronted with such moral issues, the representatives reflexively refer to the

established moral conventions of the greater part of their constituencies. Thus, they preclude opportunities for

moral reevaluation and growth. Yet, this view may depend on a skeptical view of the political process as consisting

of no more than mechanical reflection of constituent pressures.

Perry’s critics:

(1)

(2)

(3)

Whether or not representatives respond mechanically to political pressure is debatable. Thus, cutting

against Perry’s view, Maass suggests Congress often engages in some form of deliberation about what the

public good requires.

Some criticize Perry’s view because, like Justice Chase’s view, it requires the existence of right answers;

thus, it rejects moral skepticism.

Learned Hand also criticized the view citing the naivete of trusting nine Platonic guardians. Who would

chose them? He says natural law is fatal to democracy—natural law is vested in the people which delegate

to legislature so we don’t want courts to enforce against decisions made by the people.

IV. The Counter-Majoritarian Difficulty and Constitutional Interpretation

The Countermajoritarian difficulty is the tension between the basic principle that the Constitution reposes sovereign

authority in the people, who elect their representatives, and the competing principle that, in interpreting the

Constitution under the doctrine of judicial review, the courts have final say over the political process. There are

several issues involving the countermajoritarian difficulty.

(1) Mechanical Interpretation—Some suggest that the tension would be eliminated if judicial review were simply a

mechanical process of whether an Act of Congress violated the Constitution. IN such circumstances, judges

would not be imposing their own judgments about basic values, but would instead be forcing legislatures to

conform to earlier choices made by the people. The Court stated this view in U.S. v. Butler (1936). If Butler is

correct, would judges be the best people to do such mechancial interpretation? One view says judicial

insulation allows them to be impartial.

(2) Problem of the Dead Hand—Even if mechanical interpretation is the correct role, why should people be bound

to the will of dead people? Also, as Ackerman suggest, there may not be a countermajoritarian difficulty, but

an intemporal difficult since the Constitution was enacted by an ancient set of majorities.

(3) Constitutional Politics—Ackerman argues that constitutional provisions are adopted in times of appeals to the

common good, ratified by a mobilized mass of Americans expressing their assent through extraordinary

institutional forms. Judicial review protects constitutional politics from the ignorance and apathy of normal

politics. However, Brest criticizes this notion because he believes the framers also thought in terms of the

short-term and because he believes that people will become enlightened visionaries at the invocation of the

word “Constitutional.”

(4) Loss of Principle—Thayer has suggested that aggressive constitutional review by the courts has harmful

consequences for normal politics because people lose moral responsibility when they rely on the courts to

make the judgments for them. Thus, questions of principle are removed from the judicial process.

Discretionary Character of Interpretation—The discretional character of interpretation creates a counter-majoritarian

difficulty. Most concerns about judicial review focus on this concern. The Constitution is ambiguous, and the judges

have wide discretion. Thus, it becomes of central importance to find a method of constitutional interpretation that

responds to this difficulty. There are several candidates.

(a) Original Meaning, Understanding, or Intent of Framers—Original understanding disciplines judges and

diminishes the democratic problems posed by judicial review. Scalia/Thomas. However, there are several

difficulties.

1) Whose Understanding? Three problems related to how you handle {1} Drafters of the Constitution or the

state ratifiers, {b}Situations where framers disagreed, {3] framer’s silence as to a particular question.

Thus, some might emphasize original meaning as opposed to subjective original intent. Scalia argues that

these problems are real, but no more than other approaches to constitutional law.

2) Specific vs. General. Given the ambiguity of constitutional language, a judge must choose between a

particular conception fixed for all time or a general conception to be filled in over time. Equal protectionjust blacks, or other groups as well? Thus, it becomes necessary to ask whether a provision establishes

specific conceptions or general concepts. There are several views.

a) The problem of interpretive intent. From Constitutional text, it often seems plausible that the framers

intended to delegate to future people the power to make decisions about what the provision means in

particular circumstances. Dworkin says that if the general conception is chosen as original intention,

then judges must make substantive decisions of political morality in service of judgments made by the

framers. There are several views of how one decides whether specific or general.

1) Constitutional language is the best evidence, and most of the important provisions read as general

concepts.

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

(g)

2) Since if courts were empowered to wield general concepts, there would be judicial tyranny, the

framers did not intend for general concepts.

3) It’s highly unlikely to identify a valid interpretive intention on the part of the framers. There

were both general concepts and particular conceptions. The framers thus can not be understood

to have a position on interpretive intent.

b) Independent justification. Even if the framers intended to set forth particular conceptions, not

concepts, one would still have to show that their intention on that matter is binding. One might

believe that the constitutional text binds future decisionmakers, but they may decide how the

document should be interpreted. Dworkin thus believes that a decision to rely on the interpretive

intent of the framers must be independently justified.

c) Changed circumstances. Easterbrook believes that courts must uphold all measures that the framers

did not meant to invalidate, since without a decision by the framers, the judges will be unable to trace

judicial outcomes to decision made by others. However, others argue that intent cannot be

mechanically transported to a new setting; to be faithful to it, one has to engage in a difficult and

discretionary task of translation-seeing what the instructions mean in new circumstances.

Constitutional Text—Constitutional text is binding on courts. A judge would look to other constitutional

provisions that use the same words or the whole text. Also, may look to originalist sources to figure out what

the words mean. Schauer points out that there are easy textual cases. Reagan can’t run for a 3rd term, a 29year old can not be President. However, Perry argues that just about any choice the Supreme Court makes can

be within the bounds of acceptable canons of judicial behavior, even in conjunction with the constitutional text.

Tradition; Precedent—Sometimes the scope of a provision is determined in part by reference to tradition and

the Court’s own precedents. Under this approach, constitutional law operates as a form of common law,

developing over time, but constrained by the past. Strauss. However, some argue that tradition should only be

binding if one has a generally favorable view of toward the tradition. Vermeule notes that legislatures can

sometimes make precedent, i.e. if a legislature repeals a statute.

Prevailing Morality or Social Consensus “Current Values”—An open-ended constitutional provision might be

given content by referring to prevailing morality or some form of consensus. However, two problems. First, it

is not clear that judges can better register the social consensus than legislators. Second, since the Constitution

and Bill of Rights is shield against social consensus, it is inconsistent or odd to suggest that its content derives

from that consensus.

Conceptions of Justice; Principle—Courts, scholarly and insulated, set out principles, whereas legislators make

policy. Dworkin believes that the American system is not purely majoritarian. Judicial review is check on

what the democratic process can do. The judges are well-suited for this enterprise of setting out principle.

However, Brest points out that judges are old white males who do not represent true democracy. Thus, the fact

that judges make principles is skewed and undemocratic.

Commensurability—As Fallon and Sunstein recognize, most judges attempt to reconcile all these theories that

often seem in conflict. Judges are aware of the impossibility of converging on a single theory of interpretation.

Structuralism—Institutional arrangements. McCulloch.

Blackstone’s Rules of Interpretation

??

Why is the Constitution binding?

(1) The Constitution is binding because it arose out of a process in which we the people agreed to it. However,

those people are now dead, consisted of small # of ratifiers, and excluded groups of people.

(2) The Constitution is binding because the Constitution is a good one.

(3) The Constitution is binding because it is enabling rather than restraining to treat it that way. If the Constitution

were not binding, chaos would ensue.

Countermajoritarian Difficulty Escape Routes—Some suggest that, in reality, there is no difficulty, since the role of

the Court is to promote, rather than undermine, democracy, properly understood. Thus, they argue that there is no

countermajoritarian difficulty. This conclusion is buttressed by the fact that the so-called democratic process is filled

with democratic infirmities, such as disparities in wealth, race, gender, etc. There are several forms.

(1) The judicial effort to impose constitutional constraints on the political process promotes democracy, since those

constraints were adopted by the people in a time of heightened deomcratic awareness and therefore occupy a

superior status to the decisions of temporary majorities. Ackerman, Madison’s Federalist No. 78, Marbury.

(2) The role of the courts is to protect certain rights indispensible to politics and certain groups that are unable to

fully participate in politics. This inability justifies judicial review as it brings about better democracy. Free

speech,voting. McCulloch. Ely.

(3) The role of the Court is to improve democracy, but not only by protecting the opportunity of traditionally

disadvantaged groups to participate or be represented. On this view, the Court might attempt to ensure that

legislation is not a response to factional pressures.

V. The Supreme Court’s Authority over State Court Decisions

Holmes said the Union would not come to an end if no Marbury power, but it would surely come to an end if no Martin

power.

Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (US 1816) Story

Hunter claimed ownership of a piece of VA land pursuant to a grant from the state of Virginia in 1789, which had

confiscated lands owned by British subjects. Martin, a British subject, claimed that the attempted confiscation was

ineffective under anticonfiscation clauses of treaties between the United States and England. The Virginia Court of

Appeals was overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court. On remand to enter judgment, they said the U.S. Supreme

Court had no right to review whatever conclusion the state court reached because the Judiciary Act provision giving

such jurisdiction to the Court was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court held that it could indeed review the

constitutionality of a decision by a state’s highest court.

1. The text of the Constitution does not limit the Supreme Court’s appellate power to any particular courts.

(a) Art. III, §2 says the judicial power shall extend to all cases; thus, it is the case, not the court, which gives

jurisdiction.

(b) Art. III, § 3 says that, in all other cases (besides original jurisdiction cases), the Supreme Court shall have

appellate jurisdiction.

(c) If some cases may be entertained by state courts (a), and no appellate jurisdiction exists, then the appellate

power would not extend to all, but to some, cases.

(d) Therefore, Virginia’s argument that it can decide cases, but that there is no appellate jurisdiction, is

contradicted by the text of the Constitution.

2. The Supremacy clause indicates that the Framers did intend for state courts to be able to hear cases involving

the U.S. Constitution otherwise there would be no need for supremacy.

3. Since the federal judicial power extends to state courts, it must extend by appellate jurisdiction because a state

court already would have original jurisdiction.

4. The Court rejects the state sovereignty argument.

(a) The Constitution took some of the state’s sovereignty away.

(b) The Court may revise legislative and executive proceedings if they are contrary to the Constitution.

(c) Thus, since exerting such power of the judiciary is not a more dangerous act, the Court may revise judicial

proceedings.

5. The Court rejects the argument that Supreme Court review would impair the independence of state judges.

(a) State court judges are part of a federalism system; thus, they are not independent.

6. The Court rejects the argument that the Supreme Court will abuse the revising power.

(a) It is always a bad argument to argue against use on the basis of danger of abuse.

(b) Wherever the decision of last resort is, state or federal, it will equally be susceptible to abuse.

7. The Court rejects the arguments that nothing bad will happen if state court judges are left to decide as the court

of last resort because they have sworn an oath to the Constitution.

(a) The Constitution made this decision, i.e. the people made it.

(b) The Constitution presumed that state interests, jealousies, and prejudices may obstruct of the administration

of justice.

(c) The Constitution enumerates federal cases because they are more important, touching on the safety, peace,

and sovereignty of the nation.

8. In interpreting the Constitution, there is a need for uniformity of decisions throughout the nation.

(a) If no uniformity, the laws would mean different things in different states.

(b) The framers could not have intended this result.

9. Since the plaintiff may always elect state court, the defendant would not be able to try his rights in federal court,

which contradicts the theory of equal rights to the judicial power.

There are two additional justifications.

(1) Maybe state judges will be less likely to react sympathetically to federal claims-either because they lack tenure

and salary protections of Article III, and are thus more susceptible to political influence, or because of a natural

alliance with state government (similar to industry capture).

(2) Maybe federal judges have more expertise in dealing with federal law.

In response to Justice Story’s uniformity argument, why is it necessary to have uniformity of federal law? Laws

vary from state to state, why not have disparate interpretations of the Constitution?

Cohens v. Virginia (US 1821) Marshall

The Court extended and reaffirmed Martin in the context of state criminal proceedings. The state of Virginia

convicted Ds for unlawful sale of lottery tickets. Ds defense was that an Act of Congress authorized the local

government of the District of Columbia to establish a lottery. The Court concluded that the congressional statute

did not authorize the sale outside the territorial boundaries of D.C. The importance of the case lies in the holding

that the Supreme Court has jurisdiction over state criminal cases and in cases where the state is a party. Marshall

held as to the latter that the federal judicial power extends to all cases, whoever may be the party. Article III’s

language referred to “all” federal question cases.

Some question may remain as to whether the judiciary exclusively interprets the Constitution.

Cooper v. Aaron (US 1958)

Arkansas had failed to comply with a district court order requiring desegregation. The Court held once again that

federal law is the supreme law of the land, and Article VI makes it binding on the states “any thing in the state

constitutions to the contrary nowithstanding.” Every state government officer is solemnly committed to the oath

taken pursuant to Article VI, §3 “to support this Constitution.” Some have suggested that this goes beyond

Marbury in establishing a special judicial authority in interpreting the Constitution.

Since the Constitution imposes on all branches of government, not just the courts, a duty to comply with the

Constitution, a necessary inference is that executive and legislative officials must make their own judgment on

constitutional issues. Some argue that since moral issues frequently become constitutional issues, if the court’s

duty is exclusive, then politics becomes drained of morality, and political actors will make decisions based on

expediency alone.

Thayer’s Rule—Courts should strike down statutes only when the legislature has made clear mistake—so cleat

that it is not open to rational question. This rule recognizes three thrings.

(1) Many things will seem unconstitutional to one man which will not seem so to another.

(2) There is a range of choice and judgment.

(3) Whatever choice is rational is constitutional.

Thayer also believes that judicial review lessens moral responsibility of legislatures.

Underenforced Constitutional Norms—The Constitution might invalidate official action, even if the Supreme

Court declines to so hold. The Court might decide out of deference or some other reason that some measure does

not violate the Constitution, but such a holding might not bind other officials in the process of deciding whether a

proposed course of action is constitutional, since those officials are not constrained by principles of deferrrence.

Thus, there is an obligation to obey underenforced constitutional law on the part of government officials, which

requires them to fashion their own conceptions of these norms and measure their conduct by reference to these

conceptions.

C. The Sources of Judicial Decisions: Text, Representation-Reinforcement, and Natural Law

There are three possible sources of constitutional law: text, natural law, and reinforcement or improvement of

democratic processes. Roe is natural law and representation-reinforcement.

McCulloch v. Maryland (US 1819) Marshall

John James brings an action for himself and the state of Maryland against James McCulloch, cashier of a bank of

the United States, alleging that McCulloch had failed to pay a state tax assessed against the bank. The Supreme

Court held that the Bank of the United States was constitutional; thus, since the tax interfered with a valid federal

activity, the tax was unconstitutional.

1. An exposition of the Constitution, deliberately established by the legislature, on the faith of which an immense

property has been advanced, which amounts to a historical practice, ought not to be lightly disregarded. The is

such a case.

2. However, the following observation does not settle the constitutionality of the question.

3. The Constitution sets up a government of the people, not of states. Its power emantes from the people.

(a) Although the Convention which framed the Constitution was elected by the state legislatures, the people, not

the states, were the ratifies of the Constitution; thus, the people give the Constitution its authority.

(b) Although the people may have ratified in the form of states, the lines of state are natural divisions that are

more expedient than anything else.

(c) The Constitution’s preamble states that the government is “ordained and established” in the name of the

people.

(d) During ratification, state governments could not negate the votes of the people.

(e) Thus, the Court rejects Maryland’s argument that the Constitution emanates from the states, not the people.

4. The Constitution sets up a government of enumerated powers. The government can only exercise those powers

granted to it.

5. The government is supreme within its own sphere of action.

(a) The government is one of alls-it representes all, its powers are delegated by all, and it acts for all.

(b) The government, on those subjects which it can act, must be able to bind its component parts (the states).

(c) The Constitution’s Supremacy clause says it is the supreme law of the land.

(d) State legislators, executives, and judicial officers must take oath to support the Constitution.

6. Among the enumerated powers, there is no express power to establish a bank or create a corporation.

7. The Constitution contemplates the existence of implied powers.

(a) The Articles of Confederation expressly excluded incidental and implied powers. The Constitution does not.

Therefore, the framers intended for implied powers to be exercised.

(b) In reserving nondelegated rights to the states, the 10 th Amendment omitted the word “expressly;” thus, the

10th Amendment framers contemplated the existence of implied powers, especially considering the

embarrassments of the Articles of Confederation.

(c) The nature of a Constitution requires it to be a general outline.

(d) The people would not understand a Constitution that partakes the prolixity of a legal code.

(e) If the government could exercise only express powers, why would Art. I, §9 puts limitations on things not

made express. Thus, Art. I, §9 indicates an understanding that the Constitution is a general outline.

(f) “It is a Constitution we are expounding!”

8. In exercising the enumerated powers, the government is entrusted with ample means to execute them.

(a) It would be illogical to say that the framers delegated enumerated powers to the federal government in the

public good, yet impeded them from achieving that good by withholding a choice of means.

9. Since the Constitution’s included the necessary and proper clause, Congress does not have unlimited discretion

in executing the enumerated powers.

10. The Court rejects Maryland’s construction of the necessary and proper clause, which argues that the word

“necessary” means that Congress may only pass laws that are indispensible to carrying out the enumerated

powers. This argument excludes Congressional discretion from the choice of means and allows them to pass

only the necessary law which is most direct and simple. (Marshall relies mostly on perceived harmful

consequences for American government of a contrary construction, as opposed to text and history.)

(a) To employ the means necessary to an end is generally understood as employing any means calculated to

produce that end, not as the single means without which the end would be entirely unattainable.

(b) Just construction requires excessive words to be understood in a more mitigated sense-in that sense which

common usage justifies.

(c) “Necessary” has many meanings depending on context.

(d) Whereas Art. I, §10’s “absolutely necessary for executing its inspection laws” uses the qualifier “absolutely”

and the necessary and proper clause does not, the framers were cognizant of different meanings of

“necessary” and yet declined to include a restrictive qualifier in the necessary and proper clause.

(e) Narrow constructions are contrary to the idea of a Constitution established for generations to come and its

consequent need to be flexible to adapt to the various crises of human affairs.

(f) To adopt such a limiting construction would deprive future legislators of the benefit of experience.

(g) Punishment is not an enumerated power. Yet, it is expressly given in cases of counterfeiting and piracy, but

nowhere else. Thus, an inference would arise that the framers did not intend to allow punishment for other

activities. However, all agree that Congress may punish any violation of the laws.

(h) Congress may establish post offices and post roads, which are decidedly singular acts. However, it has been

inferred the power and duty to carry mail and to punish mail theft. Yet, these are not indispensable.

(i) In the absence of the clause, Congress would have discretion over the choice of means. However, a

restrictive construction would destroy this power to select the means. Thus, the framers could not have

meant such a construction.

(j) The framers also could not have meant such a narrow construction for two reasons.

a) The clause is placed among the powers of Congress, not the limitations.

b) Its terms purport to enlarge, not to diminish the powers vested in government. It purports to be an

additional power.

(k) Consequentialist. A sound construction must allow discretion for the Congress to be able to carry out its

high duties.

(l) Marshall’s understanding of congressional limitation. “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of

the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not

prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.”

11. The creation of the U.S. Bank is a necessary and proper act pursuant to fiscal operations power (which

constitutional provision?) (Hamilton argues powers of collecting taxes, borrowing money, regulating trade

between the states, and raising, supporting, and maintaining armies and navies). (David Currie says it is

striking that Marshall made no serious effort)

(a) If a corporation can be created, so can a bank.

(b) History and legislation attests the universal conviction of the utility of a bank.

12. The state of Maryland may not tax the Bank of the United States.

(a) The Constitution is the supreme law of the land.

(b) A simple corrollary:

(1) The power to create (a bank) implies the power to preserve.

(2) The power to destroy (a bank), if wielded by a different hand, is hostile to and incompatibly with the

power to create and preserve.

(3) When this repugnancy exists, the supreme authority must control.

(4) A state power to tax the Bank of the United States destroys it; thus, the Constitution controls.

(c) The nature of supremacy is to remove all obstacles to its actions within its own sphere. Thus, subordinate

government’s powers must be modified.

(d) Representation-reinforcement—Marshall finds an implicit prohibition on state taxation of the national bank.

He inquires not into text and history, but the operations of representative government. He claims that the

power to elect representatives will act as a safeguard against the abuse of political power by elected officials.

The judicial role is defined by reference to the understanding that the political process itself will ensure

against improper conduct. Marshall also indicates that the ordinary presumption disappears when a state

imposes a tax on a national instrumentality because the state is harming people who are not represented in

the state legislature. Judicial intervention is justified in order to make up for the absence of political

remedies for those burdened by legislative action. Thus, McCulloch is foundation for the notion of

representation-reinforcement, the central idea being that the judicial role is to make up for defects in the

ordinary operation of representative government; the source of judicial decision is the breakdown in political

processes.

Constitution expounding question is controversial. Frankfurter thinks it is single most important utterance in con

law. However, he also said, precisely because it is a constitution we are expounding, we should not take liberties with

it. Tidewater dissent. Moreover, Kurland argues that whenever a judge quotes this phrase, you can be sure it is

ignoring text, history, and structure in reaching its conclusion.

A constitution may be different from a statute in the sense that a constituion must be broad, whereas a statute need

not be (although it probably does? Agencies).

There are several views of Marshall’s position.

(1) The power-granting provisions of the Constitution should be broadly construed. Those provisions are meant to

endure over time. Flexible interpretation assists when unforeseen problems arise. But this does not mean that

courts may strike down legislation based on changed circumstances.

(2) All Constitutional provisions should be broadly construed. Constitutions simpy do not contain specific

answers to questions all the time.

(3) Constitutional meaning changes with changing circumstances, in accordance with changing social norms and

needs. Judges need not adhere to specific framer’s intent, but must interpret document flexibly in light of

contemporary necessities.

McCulloch v. Marbury—One view says that —One view says that Marbury rested on perception that interpretation

process was mechanical. That understanding was the ground on which judicial review was built. In McCulloch, a

difference arises, judges are recognized as having considerable discretion.

Hamilton and Madison disagreed over the constitutionality of the Bank of the U.S.

Black, pointing to Marshall’s use of structures and relationships, says this approach is preferable. Text binds judges

even if it doesn’t make sense. Structuralism lets us consider practicalities and proprieties of things. We get to deal with

policy not grammar.

II.

Limits on Judicial Power

Article III, §2’s “case of controversy” requirement forbids courts from invalidating legislative or executive action

merely because it is unconstitutional. The courts may only rule in the context of a constitutional case. Such a rule

serves several purposes.

(1) Judicial Restraint—By limiting the occasions for judicial intervention into legislative and executive processes,

the case or controversy requirement reduces the friction between the branches produced by judicial review. This

rationale is often tied to a concern with the countermajoritarian difficulty.

(2) Ensures Concrete Disputes—The requirement ensures that constitutional issues will only be resolved in the

context of concrete disputes rather than in response to problems that may be hypothetical, abstract, or

speculative.

(3) Promotion of Individual Autonomy—The requirement promotes the ends of individual autonomy and selfdetermination by ensuring that constitutional decisions are rendered at the behest of those actually injured rather

than at the behest of bystanders attempting to disrupt mutually advantageous accomodations or to impose thier

own views of public policy on government. This rationale is sometimes accompanied by a suggestion that the

requirement ensures real adversity between the parties and thus ensure against collusive litigation. However,

sometimes a law suit will not result because of ignorance, poverty, or alienation rather than from satisfaction

with the status quo.

Bickel’s ‘The Least Dangerous Branch’ (1965)

The case or controversy requirement accomplishes two things. (1) It functions as a national second thought.

After the legislature passes the law, a court can see how it plays out in consequence and reconcile any

unforeseen problems. (2) It creates a time lag between legislation and adjudication so as to cushion the clash

between the Court and any given legislative majority. Furthermore, Bickel believes that the “passive virtues” of

inaction operate as a necessary means of mediating between the two competing ideas at work in U.S.

government: electoral accountability and governance according to principle. The “passive virtues’ operate to

ensure that the latter idea does not swallow up the former, by permitting the Court to defer to the political

process without resolving the issue either way.

Gunther’s ‘The Subtle Vices of the Passive Virtues’

Objects that an unprincipled approach to justiciability issues is unacceptable and will ultimately undermine the

Court’s role.

The justiciability doctrine is rooted in 20th century attempts by Frankfurter and Brandeis seeking to immunize

progressive government and administrative agencies from judicial review. The Framer’s did not establish it.

1.

Advisory Opinions

Under President Washington, the Supreme Court said that it was unconstitutional to issue advisory opinions. The

Supreme Court cited separation of powers and its special role as a court of last resort as reasons for forbidding

advisory opinions. The executive power to call on heads of departments for opinions (Opinions and Writing Clause)

is limited to the executive branch. Some other people suggest that an advisory body would end up having close

collegial relations with those to whom they gave advice undermining independence of the judiciary.

Two kinds of advisory opinions.

(1) Binding—Framers rejected Council of Revision, which could veto legislation on constitutional grounds.

(2) Advice—Truman and Vinson’s poker games.

Some of the advantages of the advisory opinion idea is furnished by the declaratory judgment procedure. Also, the

Office of Legal Counsel of the DOJ has assumed advice-giving role for executive.

2.

Standing

Legal Right Model—An Article III “case” requires that a case involve a legal right. To make a case between A and

B, A has to have a legal right against B, and apply to court for redress. There is little difference between standing and

winning on the merits. The bite of this whole model is in cases where there is no extralegal harm, i.e. Lujan.

Particularized Injury Model—A concrete injury is a necessary and sufficient condition for a law suit. The bite of

this model is that it says that some legal rights do not confer standing. Modern standing model.

Association of Data Processing Services Organization v. Camp (US 1970)

In this case, the Court boldly altered previous law by abandoning the legal injury test altogether for the injuryin-fact test. Several things are notable.

(1) The decision purported to be an interpretation of the Administrative Procedure Act, not of Article III; the

injury-in-fact test was said to be a part of the APA.

(2) The Court clearly intended to broaden standing doctrine, emphasizing that the injury-in-fact requirement is

relatively lenient. According to the Court, it may include a wide variety of economic, aesthetic,

environmental, or other harms.

(3) The consequence of this case is that beneficiaries of government regulation, not merely those trying to

fend off government action, have standing to sue.

a. Constitutional and Prudential Limits—The Court has broken down standing limitations into constitutional

and prudential limits. A Court can raise this issue sua sponte.

Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United (US 1982)

1. The Article III limitation requires the party who invokes the court’s authority to show three things.

(a) He has personally suffered some actual or threatened injury as a result of the putatively illegal conduct of

the defendant.

(b) The injury can be fairly traced to the challenged action.

(c) The injury is likely to be redressed by a favorable decision.

2. Beyond these constitutional requirements, the federal courts have also crafted three prudential limitations.

(a) The plaintiff generally must assert his own legal rights and interests and cannot rest his claim to relief on

the legal rights or interest on 3rd parties. Only difficulty is when you have parties that stand in some

parental or professional relationship to some party.

(b) Even when the plaintiff has alleged redressable injury sufficient to meet Article III’s requirement, the

Court refrains from adjudicating abstract questions of wide public significance which amount to

generalized grievances, pervasively shared and most appropriately addressed in Congress.

(c) The plaintiff’s complaint must fall within the zone of interests to be protected or regulated by the statute or

constitutional guarantee in question.

b. Underlying Concerns

There are several function served by standing doctrine.

(1) It ensures that courts will decide cases that are concrete rather than abstract or hypothetical.

(2) It promotes judicial restraint by limiting the occasions for judicial involvement in the political process. This

rationale may be criticized as an arbitrary means of accomplishing judicial restraint, but the fact that injuries

to citizens at large are not cognizable judicially, but only politically, responds to such criticism.

(3) It ensures that decisions will be made at the behest of those directly affected rather than on behalf of

outsiders with a purely ideological interest in the controversy. This factor will promote vigorous advocacy.

Two problems: (1) Sometimes those directly affect will fail to sue for reasons other than the contentment

with the status quo. (2) A theory is needed to decide who is “directly affected” and who is an “outsider.”

(4) It is an important part of the separation of powers system by ensuring that courts will not hear cases simply

because they want to. Instead, by requiring a concrete stake, it gives the executive and legislative branches

breathing room.

c. Doctrinal Components

1. Injury in Fact—The injury-in-fact requirement evolved over a long period of time. The roots of modern

standing law, however, can be traced to the following case. Sierra Club, Lyons. How do we define the injury?

Cass Sunstein wants to put it in terms of common law baselines, such as property interest, etc. Millian thesis

says that only things that count as harms are tangible harms. The bare knowledge of harm is not harm.

(Inconsistent with tort system’s emotional distress—indeterminacy).

Sierra Club v. Morton (US 1972)

The Sierra Club alleged that it had a special interest in the conservation and sound maintenance of national

parks by which it could challenge construction of a recreation area in a national forest. In their view, the

construction would have violated federal law. The Court denied standing saying that the fact that an aesthetic,

conservational, or recreational harm would be sufficient did not mean that the Court would abandon the

requirement that the party seeking judicial review must have himself suffered an injury. The Sierra Club failed

to allege that it or its members used the site in question.

United States v. Scrap (US 1973)

The Court held that environmental groups could challenge the ICC’s failure to suspend a surcharge on railroad

freight rates as unlawful under the Interstate Commerce Commission Act. The plaintiffs claimed that their

members used forests, streams, mountains, and other resources in the Washington area for camping, hiking,

and sightseeing. The Constitution was satisfied by the attenuated line of causation to the injury—a rate increase

would cause increased use of nonrecyclable commodities, resulting in the need to use more natural resources to

produce such goods, some of which might be taken from the Washington area, resulting in more refuse that

might be discarded in Washington’s national parks.

Scrap may not be able to command a majority today.

Allen v. Wright “stigmatic injuries” p. 102 ?????

According to Duke Power and SCRAP, the injury-in-fact requirement is usually met by those who can show

a sufficient threat of future injury. The threat must be real and immediate rather than speculative or

hypothetical. This plays an important rule in suits seeking injunctive relief.

City of Los Angeles v. Lyons (US 1983)

Lyons brings action against L.A.P.D. seeking injunctive relief to prevent the use of choke holds, of which he

was a victim. Lyons also brought a suit for damages. The Court held that this latter fact did not mean that

he could also obtain an injunction when he was not likely to suffer any future injury from the use of

chokeholds by police officers.

2. Widely Diffused Harms—A widely diffused harm is one where many or all citizens feel it equally.

Schlesinger v. Reservists to Stop the War (US 1974)

A Reservist group alleges that several congressman’s reserve status violates the Incompatibility clause. The

Court held that the Reservist’s only interest was a general one shared by all citizens in proper constitutional

governance, which is an abstract injury. To hold otherwise would provide potential for abuse of the judicial

process, distort separation of powers, and open the Court up to a charge of government by injunction. In

addition, the Reservists did not meet the requirements of Flast v. Cohen.

United States v. Richardson (US 1974)

A taxpayer challenges the CIA Act of 1949, permitting CIA expenditures to be made public, as violative of the

Accounting clause. Finding a generalized grienvance, the Court stated that the taxpayer did not allege he is in

danger of suffering any particular concrete injury as a result of the operation of the statute. The Court added

that the very fact that no one will be able to litigate this issue gives support that the political process is the only

recourse available.

Concurrence (Powell)

The Court has always expressed its antipathy to efforts to convert the judiciary into an open forum for the

resolution of political disputes about the performance of government. Several considerations underlie this.

(1) As in the public reaction to the New Deal’s substantive due process holdings, it is believed that history

will repeat itself again. ???

(2) The Court should not divert limited resources to resolution of public-interest suits brought by litigants

who cannot distinguish themselves from all citizens.

(3) Judicial review over cases or controversies maintains public esteem and permits the peaceful existence

of the countermajoritarian implications of judicial review and the democratic principle.

The generalized grievance problem frequently arises in taxpayer standing cases.

Flast v. Cohen (US 1968)

A taxpayer challenges aid to religious schools as violative of the establishment clause. In a rare recognition of

taxpayer standing, the Court found standing because there was a logical nexus between the status asserted and

the claim thought to be adjudicated. The nexus demanded of federal taxpayers has two aspects to it.

(1) The taxpayer must establish a logical link between the status and the type of legislative enactment

attacked. It will not be sufficient to allege an incidental expenditure of tax funds in the administration of

an essentially regulatory measure.

(2) The taxpayer must establish a nexus between that status and the precise nature of the constitutional

infringement alleged. The taxpayer must show that the challenged enactment exceeds specific

constitutional limitations imposed upon the exercise of the congressional taxing and spending powers.

Fronthingham v. Mellon (US 1923)

The Court refused taxpayer standing where a taxpayer sought to enjoin under the 10 th Amendment

expenditures made to reduce maternal and infant mortality under federal statute.

Valley Forge Christian College v. Americans United (US 1982)

The Court refused taxpayer standing where a taxpayer challenged under the Establishment clause a conveyance

of property formerly used as a military hospital to the Valley Forge Christian College. The Court emphasized

that the plaintiffs challenged a property transfer, not an expenditure of funds.

There are three views of whether a widely diffused injury/generalized grievance is a sufficient basis for judicial

relief.

(1) Richardson, Schlesinger, and Valley Forge are right, Flast is wrong. If there is a generalized grievance,

the appropriate forum is the legislature. The mechanism of political accountability are a sufficient

guaranty. If those mechanisms fail, the problem must not be severe enough in any event.

(2) Richardson, Schlesinger, and Valley Forge are wrong because they render constitutional restraints

unenforceable. Constitutional requirements are not meant to vary with public opinion; they operate

largely as constraints on outcomes, even if they accurately reflect popular opinion. If plaintiffs in those

cases do not have standing, no one ever will.

(3) The real standing question is whether any law creates a cause of action. When a constitutional provision

benefits all citizens, courts should not infer from it a cause of action on behalf of any citizen in particular.

Flast is a sensible exception because of the distinctive character of the establishment clause, a guarantee

against the expenditure of taxpayer funds for religion.

3. Nexus—As suggested by Allen and Valley Forge, the nexus requirement has two prongs; however, in

practice, the two prongs almost always amount to the same thing. The plaintiff must show that:

(a) The allegedly unlawful conduct has caused the injury in fact.

(b) The injury is likely to be redressed by a favorable decision.

Linda R.S. v. Richard D. (US 1972)

An unwed mother of an illegitimate child brings an action to enjoin discriminatory application of a Texas

criminal statute that penalized any parent who failed to support his children. Plaintiff contended that judicial

interpretation excluded illegitimate fathers from prosecution and sought to require a prosecutor to initiate

criminal proceedings for failure to provide child support. The Court denied standing because they believed

prosecution might lead only to the father’s incarceration, not in payment of support.

One view is that the plaintiff’s claim in this case involved unequal treatment, and if the injury is one of

inequality under the law, there is no problem of redressability.

Easterbrook’s ‘The Court and the Economic System’ (1984)

It is incorrect to say that enforcement of legal rules does not affect bystanders. I suffer an injury if the police

announce they will no longer enforce rule against murder in my neighborhood. A plaintiff need not show a

sure gain of winning in order to prove that some probability of gain is better than none, thus he suffers an

injury in fact.

Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welfare Rights Organization (US 1976) Powell

Several indigents and organizations challenged IRS ruling that granted favorable tax treatment to certain nonprofit hospitals that limited aid to indigents to emregency room services. Plaintiff’s theory was that the ruling

was unlawful because it reduced amount of services necessary to qualify as charitable corporations; thus, they

would have less medical services available to them. The Court held that there was no standing because it was

speculative whether the denials of service could be traced to the IRS’s encouragement. It is also speculative

whether the Court would be able to remedy the problem so that the result is availability of services. Causation

case.

Concurrence (Brennan, Marshall)

The relevant injury is the opportunity and ability to receive free medical services. Furthermore, the plaintiff’s

interest was not too diffuse to support standing. Finally, the further requirement imposed by the Court served

no purpose.

Warth v. Seldon (US 1975)

Various organization and individuals in Rochester, N.Y. bring action against the town of Penfield to enjoin

application of its exclusionary zoning ordinance. The Court denied the assertion of standing by people of low

or moderate income and as members of minority groups. The Court emphasized that the plaintiff failed to

show that their inability to locate housing in Penfield resulted from Penfield’s statutory and constitutional

violations. They were required to show a substantial probability that they would have been able to buy land in

Penfield, and that, if the Court affors the relief requested, the inability would be removed.

Concurrence (Brennan)

The plaintiffs cannot be expected to know, prior to discovery and trial, the future plans of building companies,

the details of the Penfield housing market, etc. To require them to allege such facts reverts back to factpleading days.

Duke Power Co. v. Carolina Environmental Study Group (US 1978)

Plaintiffs—40 people who lived near power plants, an environmental group, and a labor organization—sought

a declaration to challenge the Price-Anderson Act, which limited aggregate liability for a nuclear power plant

accident to $560 million. The Court found a sufficiently concrete injury in plaintiff’s in the environmental and

aesthetic consequences of the thermal pollution of the two lakes in the vicinity of the disputed power plants.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (US 1978)

Plaintiff challenged an affirmative action program established by UCD without alleging that, if the program

were not in place, he would have been admitted to the medical school. The Court upheld as sufficient the trial

court’s characterization of the injury as the University’s decision not to permit Bakke to compete for all 100

places in the class, simply because of his race.

This may suggest that EKWRO and Warth are wrongly decided. Notice that whether the injury is

speculative depends on how it is characterized, i.e. an opportunity or a more common law-type one.

Chayes’s ‘Public Law Litigation and the Burger Court’ (1982)

Suggests that characterization of the injury is dispositive in standing cases. How an injury and causation is

characterized depends on the interests and sympathies of shifting configurations of five Justices.

Diamond v. Charles (US 1986)

The Court held that a pediatrician who had intervened below to defend a state’s criminal statute regulating

abortions lacked standing to appeal when the state itself failed to seek review of a decision enjoining

enforcement of the statute.

(1) Even if the abortion law was constitutional, the Court held that the pediatrician could not compel the state

to enforce it against violators because a private citizen lacks a judicially cognizable interest in prosecution

of another.

(2) The Court found that the pediatrician’s alleged injury of financial gain derived from more live births was

too speculative that the babies would ever be his patients.

(3) The Court held that an award of attorney’s fees is not a direct stake/injury because the mere fact that

appeal could provide a remedy for this award is only a byproduct of the suit itself.

Maine v. Taylor (US 1986)

A Maine fisherman was prosecuted under a federal law prohibiting the importation of live baitfish into a state

that prohibits it. Maine intervened to defend the constitutionality of its statute. The lower court found the ME

statute constitutional. The 1st Circuit reversed. The U.S. sought no further review, but ME appealed to the

Supreme Court. The Court held that ME had a sufficient stake in the outcome to give it standing because a

state has a legitimate interest in the continued enforceability of its own statutes.

4. Injuries to 3rd Parties and “Zone of Interests”

“Third Parties”—Third parties must litigate their own rights.

“Zone of Interests”—Derived from Data Processing, a plaintiff must show that he is within the zone of interests

protected by the statutory scheme. In the constitutional context, the plaintiff must be an intended beneficiary of

the constitutional provision at issue. This requirement has never been the basis for denying standing in a

constitutional case, but has occasionally in other cases.

Possibly, the following two cases have started reassert the view that standing is ultimately a question of

substantive law: whether relevant statutes and constitutional provisions confer on the plaintiff a right to bring

suit.

Air Courier Conference v. APWU (US 1991)

Postal Service employees challenge Postal Service decision to partly relinquish its monopoly of the mails by

allowing private courier services to engage in ‘international remailing.’ The court concluded that the

employees were not within the zone of interests of the statutes creating a national postal monopoly, which

Congress did not enact to protect Postal Service jobs.

International Primate Protection League v. Administrators (US 1991)

Plaintiffs challenge use of certain monkeys in federally funded medical experiments. The action was filed in

state court and removed to federal court. The Court held that the right to sue in state court was an injury

traceable to the challenged action and likely to be redressed by the remedy sought; thus, plaintiff had standing

to contest the removal. The Court said that standing should be seen as a question of substantive law,

answerable by reference to the statutory and constitutional provision whose protection is invoked.

Following this line of reasoning, there are few or perhaps no limits on Congress’s power to confer standing.

The Court, however, has not always recognized this standing analysis, which was the framer’s position.

Fletcher’s ‘The Structure of Standing’ (1988)

Reemphasizes this notion of the true standing question and calls for reexamination of all current standing law.

He also urges that where a constitutional violation is at issue, the question is whether the constitutional

provision confers on the plaintiff a right to relief.

Sunstein and Currie hold similar views.

Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife (US 1992) Scalia

[111]

Plaintiffs, an organization dedicated to wildlife and other environmental causes, brings this action against the

Secretary of the Interior seeking a declaratory judgment that the Endangered Species Act of 1973 extends to

foreign nations, not to just the U.S. and high seas, as well as an injunction requiring the Secretary to

promulgate a new regulation restoring the initial interpretation.

1. When plaintiff’s injury arises from the government’s unlawful regulation of others, as opposed to situations

where he himself is the object of the regulation, standing is not precluded, but is substantially more

difficult to establish. Summary judgment more difficult too.

2. The complaint contains no facts showing how damage to the species will produce injury to the two women.

(a) A previous visit proves nothing.

(b) “Some day intentions”—without any description of concrete plans, or indeed even any specification of

when the some other day will be—do not constitute an actual or imminent injury.

3. The ‘ecosystem nexus,’ ‘animal nexus,’ and ‘vocational nexus’ theories all fail because they do not require

an injury in fact.

4. There can be no redressability in this case. (Not opinion of the court, only Scalia, Rehnquist, Thomas, and