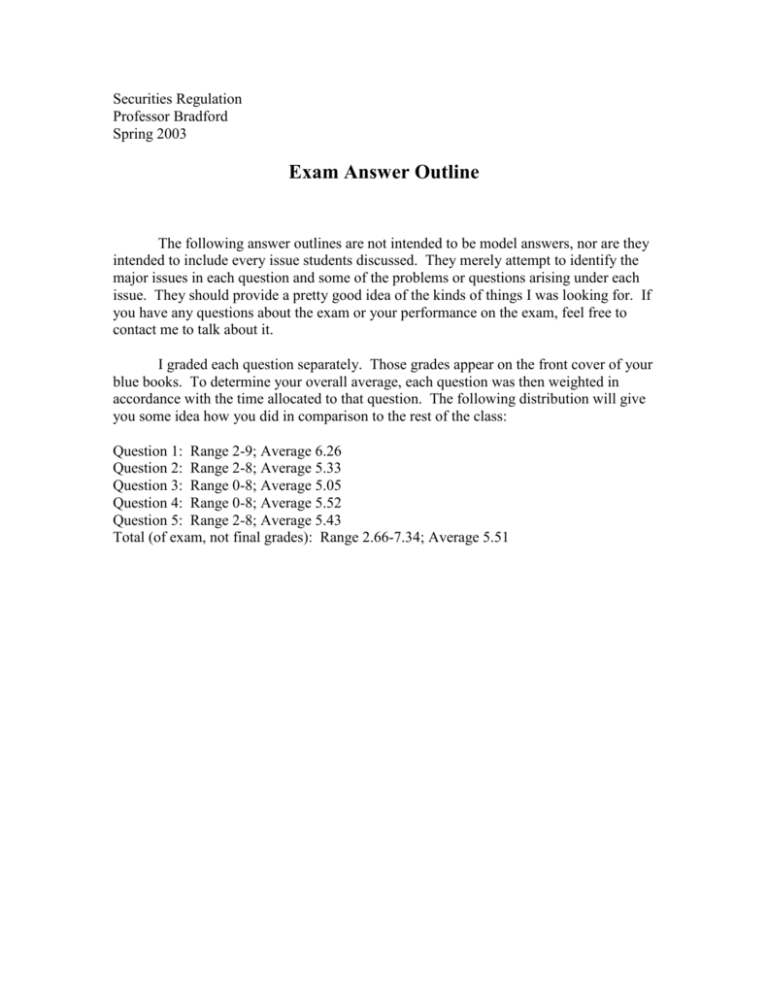

Spring 2003

advertisement

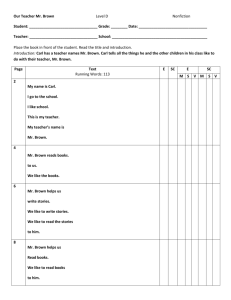

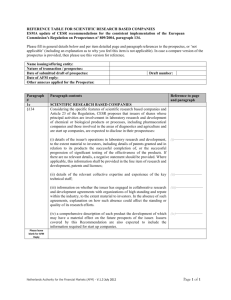

Securities Regulation Professor Bradford Spring 2003 Exam Answer Outline The following answer outlines are not intended to be model answers, nor are they intended to include every issue students discussed. They merely attempt to identify the major issues in each question and some of the problems or questions arising under each issue. They should provide a pretty good idea of the kinds of things I was looking for. If you have any questions about the exam or your performance on the exam, feel free to contact me to talk about it. I graded each question separately. Those grades appear on the front cover of your blue books. To determine your overall average, each question was then weighted in accordance with the time allocated to that question. The following distribution will give you some idea how you did in comparison to the rest of the class: Question 1: Range 2-9; Average 6.26 Question 2: Range 2-8; Average 5.33 Question 3: Range 0-8; Average 5.05 Question 4: Range 0-8; Average 5.52 Question 5: Range 2-8; Average 5.43 Total (of exam, not final grades): Range 2.66-7.34; Average 5.51 Question 1 Broker’s contact with Client occurred on March 30, after the March 1 effective date. Absent a refusal order or stop order, the only part of section 5 that applies after the effective date is section 5(b). Section 5(a) only applies “unless a registration statement is in effect,” and one is. Section 5(c) only applies “unless a registration statement has been filed,” and one has. Section 5(b)(1) makes it unlawful for any person, using, among other possibilities, the mails, to transmit a prospectus, unless it meets the requirements of section 10. Broker used the mails, so the jurisdictional requirement is met. Nothing in section 5 limits its coverage to offering participants, so Broker’s actions could be covered. Section 2(a)(10) defines “prospectus as, among other things, a written communication which offers any security for sale; it expressly includes letters within its terms. An offer to sell is “every attempt or offer to dispose of, or solicitation of an offer to buy, a security . . . , for value.” Section 2(a)(3). Broker is attempting to interest Client in purchasing Seedling stock and that purchase would clearly be for value, so the letter appears to be a prospectus within this broad definition. This letter does not fall within the section 2(a)(10)(a) free-writing exception because it was not accompanied or preceded by a section 10(a) final prospectus. And the letter does not fall within the section 2(a)(10)(b) exception or its Rule 134 expansion because it includes more than either allows, and does not include the mandatory language. This letter also does not meet the requirements of section 10. Gustafson limits the term “prospectus” to public offerings, but this is a registered public offering, so that is not a concern. However, there is also language in Gustafson equating prospectuses to carefully drafted documents of wide public dissemination. If that dictum is followed, this personal letter would not qualify as a prospectus and there would be no section 5(b)(1) violation. Assuming the letter is a prospectus, Broker has violated section 5(b)(1) unless he has an exemption. The section 4(1) exemption is not available because Broker, a professional broker, is a dealer. Section 2(a)(12). The section 4(4) exemption is not available because Broker is not merely executing Client’s purchase order. The letter is soliciting the purchase and section 4(4) excludes “the solicitation of such orders.” Section 4(3), as modified by Rule 174, is available, however. Section 4(3) excludes transactions by a dealer, except for transactions within a specified time after the effective date or the first offer, whichever is later. Ordinarily, for IPOs, the relevant time period is 90 days, which would not help Broker. His letter was clearly sent within 90 days of the effective date. However, Rule 174 shortens that time period in certain cases. Rule 174(d) reduces the time to “twenty-five calendar days after the offering date” if “as of the offering date, the security is . . . authorized for inclusion in an electronic inter-dealer quotation system sponsored and governed by the rules of a registered securities association.” This is a reference to NASDAQ, and Seedling’s common stock was authorized for trading on that system as of the offering date. “Offering date”, for purposes of this rule, is the later of the effective date or the date of the first bona fide offer to the public. Rule 174(d). Broker’s letter was more than 25 calendar days after the effective date, so it is exempted from section 5 by section 4(3) as modified by Rule 174(d). Broker did not violate section 5. Question 2 Coverage of Section 12(a)(2). Section 12(a)(2) imposes liability for misleading statements made “by means of a prospectus or oral communication.” The allegedly misleading statement here was oral—the statement in the elevator. A prospectus must be written, or on radio or T.V. Section 2(a)(10). The Supreme Court in Gustafson indicated that “oral communications” in section 12(a)(2) is limited to oral communications relating to prospectuses—which the Court indicated is limited to public offerings. This is clearly a registered public offering but, when the Court required oral communications to be related to a prospectus, did it mean that the oral statement must be directly concerned with the prospectus, or merely that it must be in a public offering. This statement is not directly related to the contents of the prospectus, because the prospectus says nothing about the Superior contract, but that’s probably not a requirement. Materially Misleading. Finance’s statement clearly is misleading. He said he was sure IHOP would get the Superior contract even though, at the time, Superior had dropped IHOP from the bidding. A misstatement is material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important. TSC Industries. Without more details about the size of the company and the size of the contract, it is impossible to know for sure if it’s material, but it probably is, since it’s a multi-milliondollar contract. However, it is not clear from the problem was else the market knew about the bidding process for Superior’s contract. If the market knew that IHOP had been dropped from the bidding, that should be reflected in the price IHOP is able to get for its stock, and Finance would have a “truth-on-the-market” defense similar to that in Wielgos. Seller. To be liable, Finance must have offered or sold the security to Buyer. Pinter v. Dahl was a section 12(a)(1) case, but the relevant language of section 12(a)(2) is the same, and it is accepted that Pinter also applies to section 12(a)(2). Finance did not directly sell any securities to Buyer, so he is not a seller in the title-passing sense. Therefore, he is a seller under Pinter v. Dahl only if he solicited Buyer for value—to serve his own or the issuer’s personal interest. Finance did not purposely solicit Buyer, but his statement would be considered an offer under the broad reading of “offer to sell” in section 2(a)(3)—it would affect Buyer’s willingness to purchase the IHOP stock. The real question is whether the solicitation has to be intentional—did Finance “attempt” to offer the stock to Buyer? If he did, he probably did so for value. As CFO of IHOP, he was serving the financial interests of IHOP in his conversation with Pro. Reasonable Care Defense. If he is a seller, Finance may still avoid liability by showing that “he did not know, and in the exercise of reasonable care could not have known, of such untruth or omission.” Finance did not know what he was saying was untrue, although he certainly was reckless. Given his position, a single phone call would have provided an answer. Although most courts don’t believe section 12(a)(2) creates a duty of inquiry, but see Sanders v. John Nuveen, it’s hard to see how making statements deliberately with no knowledge of whether or not they were true, when that knowledge is easily obtainable by the speaker, could constitute reasonable care. Buyer’s Knowledge. Buyer did not know of the untruth, so the defense in the parenthetical in section 12(a)(2) does not apply, and a plaintiff clearly has no duty to investigate under section 12(a)(2). Damages. The ordinary measure of damages in a section 12 action is rescission—Buyer can recover the full purchase price, since he still owns the security. However, section 12(b) provides a negative causation defense. Finance is not responsible for any part of the loss he can show did not result from the misleading statement. Finance will try to argue that, since the price did not drop when the truth was announced, the fraudulent statement had no effect. See Ackerman (dealing with a similar issue under Section 11’s negative causation defense). However, IHOP’s announcement of a government contract on the same day could have masked any negative effect. Moreover, the news might have leaked out earlier, and explain part of the earlier drop (although the fact that the market as a whole was also falling cuts against that argument). Buyer could also argue that the lie never affected the market in the first place, since it was a private conversation in an elevator. However, the representatives of several large institutional investors were also in the elevator; if the lie was material, it is unlikely there was no positive effect on the market. The key is whether the court will follow Ackerman in deciding that the lack of a post-announcement price reaction shifts the burden to the plaintiff. Whoever has the ultimate burden is likely to lose. Question 3 Rule 506 is a safe harbor for the section 4(2) private offering exemption, and therefore its policy rationale is the same as that for section 4(2). As the Supreme Court indicated in Ralston Purina, the private offering exemption is limited to those who are “able to fend for themselves” and therefore do not need the protection Securities Act registration provides. To be able to fend for themselves, these investors need access to the kind of information registration would provide and sufficient sophistication to evaluate that information. Rule 506 does not exactly fit that policy rationale. For one thing, its 35-purchaser limit, Rule 506(b)(2)(i), seems a little odd in this context. The number of purchasers in the offering seems irrelevant to their need for protection; Ralston Purina itself discounted the importance of the number of investors. As to non-accredited investors, the sophistication requirement in Rule 506(b)(2)(ii) seems appropriate to the policy rationale. The provision for a sophisticated purchaser representative for an unsophisticated investor also fits the rationale, particularly given the conflict-of-interest provisions in Rule 501(h). The representative’s sophistication can protect the unsophisticated purchaser. However, the Rule 506(b)(2)(ii) sophistication requirement does not apply to accredited investors and it is here that the fit to the policy rationale breaks down a little. Some of the accredited investors in Rule 501(a)—such as most broker-dealers, banks, and investment companies—undoubtedly are sophisticated enough that they don’t need the protection of registration. But that is probably not true for many of the people in other categories. For example, is a natural person whose joint income with her spouse is $300,000 [Rule 501(a)(6)] necessarily sophisticated with respect to investment matters? And many people today who have assets with a value in excess of $1 million [Rule 501(a)(5)] aren’t that sophisticated, particularly when the value of retirement assets is included. For that matter, does every corporation with $5 million in assets [Rule 501(a)(3)] really have investment sophistication? That is not a particularly large business by today’s standards, particularly if the business is some type of manufacturing. Moreover, Rule 506 does not perfectly fit the access to information aspect of Ralston Purina. Rule 502(b)(1) requires that information be provided to non-accredited investors, but it does not require that accredited investors be furnished the same information. They have an opportunity to request information, Rule 502(b)(2)(v), but, as discussed above, not all of the accredited investors will have sufficient sophistication to ask for, or sufficient bargaining power to obtain, the information necessary to evaluate the investment. Finally, it’s not clear that the prohibition on general solicitation is necessary to satisfy the policy rationale for Rule 506. If all the eventual purchasers are able to fend for themselves, why should it matter how the issuer contacted those purchasers, or whether the issuer also contacted other potential purchasers who aren’t sophisticated, as long as the issuer doesn’t sell to the unsophisticated offerees? Question 4 Nothing in section 5 of the Securities Act limits its application to sales by the issuer, so Cash is required to register unless he has an exemption. The common exemption for resales is section 4(1)—“transactions by any person other than an issuer, underwriter, or dealer.” Section 4(1) The issuer, Exxam, is not involved in Cash’s resales. Fleecam is a professional broker, which makes her a dealer. Section 2(a)(12). However, if that’s the only problem, the section 4(3) exemption would exempt her since Cash’s shares are not part of an underwriter’s unsold allotment and the required time period has expired since the Exxam offering was 18 months ago. Thus, Cash has the section 4(1) exemption unless his resales involve an underwriter. Fleecam is not an underwriter, unless Carl is and it’s participating in his underwriting. Fleecam is not selling for an issuer (or control person) in connection with a distribution, since Carl is not a control person. However Carl himself might be an “underwriter” as defined in section 2(a)(11) if he purchased from the issuer, Exxam, with a view to distribution. It’s not clear if Carl’s 18-month holding period is sufficient to establish investment intent. The case law under the statute saw two years as the turning point; after that, investment intent was presumed. However, Rule 144 has now shortened its holding period to one year, so perhaps the case law under section 4(1) would also be adjusted. If this is long enough to establish investment intent, Carl is not an underwriter. Carl can also establish investment intent by showing a change of circumstances since his purchase of the Exxam shares. However, his impending retirement is something he could have anticipated 18 months ago. Therefore, unless his retirement was unexpected for some reason, he cannot show an adequate change of circumstances. In any event, the SEC purported to abolish the “change of circumstances” test when it adopted Rule 144, although it’s not clear it has the authority to do this, since this test is an interpretation of the “purchased with a view” language in the statute. If Carl can’t establish investment intent, and therefore the securities have not come to rest from Exxam’s offering, Carl is an underwriter only if his resales constitute a “distribution.” Before the issuer’s offering comes to rest, resales constitute a distribution if the resales are inconsistent with the issuer’ original exemption. Carl’s resales would clearly be inconsistent with Exxam’s Rule 505 exemption. Rule 505(b)(2)(ii) says the securities may be sold to no more than 35 purchasers, although this excludes accredited investors. Rule 501(e)(iv). Exxam sold to exactly 35 nonaccredited investors. If Carl resells to 15 individuals, only half of whom are accredited, the securities will come to rest in the hands of more than 35 nonaccredited purchasers, a violation of Rule 505(b)(2)(ii), and therefore inconsistent with Exxam’s exemption. Carl would therefore be an underwriter if he is unable to establish investment intent. Rule 144A The Rule 144A safe harbor would be unavailable to Carl because it limits sales to qualified institutional buyers. Rule 144A(d)(1). These individuals are not institutions. See Rule 144A(a)(1). Rule 144 The Rule 144 safe harbor also would not work. These are restricted securities under Rule 144(a)(3)(ii) because they are subject to the Regulation D resale limitations. Therefore, Rule 144 would be available if all the conditions of the rule are met. Rule 144(b). Carl has held the stock for the one-year period required by Rule 144(d), but not, unfortunately, for the two-year period after which the conditions are relaxed for noncontrol persons. See Rule 144(k). Exxam appears to meet the current public information requirement of Rule 144(c), since it is an Exchange Act reporting company and has filed its reports on time. But Carl does not meet either Rule 144(e) or (f). Rule 144(e) limits the amount of securities Carl can sell to the greater of 1% of the shares of the class outstanding, Rule 144(e)(2), (1)(i) [1% of 1,000,000 is 10,000] or the average weekly trading volume, Rule 144(e)(1)(ii),(iii) [20,000]. Carl cannot sell more than 20,000 shares and he wants to sell 25,000. In addition, Rule 144(f) says the shares must be sold in a broker’s transaction, which precludes solicitation by the person selling the securities. Rule 144(f)(1). Rule 144(g)(2)(ii) relaxes this slightly, allowing Felicia to solicit customers who have expressed an interest in the securities in the past ten business days, but it’s unlikely all 15 individuals fall within this. Thus, Rule 144(f) is also not met, so Rule 144 is unavailable to Cash. Question 5 There are two ways in which this ad might be misleading. First, the statement that Linkcyst cards are “The Best in the World: No One Else Comes Close” is arguably misleading because most experts believe there are technically superior Ethernet cards. Second, stating that Linkcyst has 85% of the market while omitting the rumors about Macrohard’s potential entry into the market could be misleading. A fact is material if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important in deciding how to act. TSC Industries. Best in the World Statement The first statement appears to be mere puffery; most people would not expect this to have much meaning. The appearance of this statement in an advertisement rather than in a financial context reinforces this argument. Furthermore, Linkcyst may believe its cards are the best in the world, no matter what most of the experts say. And, if only “most” of the experts believe there are technically superior cards, at least some of them must think Linkcyst’s cards are the best. Even the experts who believe other cards are technically better may believe Linkncyst’s card is best when price is considered. Moreover, the experts’ opinions are probably public, so there’s a truth on the market defense. See Wielgos. If the market is already aware of the experts’ opinions, this statement would not have any effect on the market price. 85% Market Share Statement The second statement is more difficult. Omitting Macrohard’s planned entry while claiming an 85% market share is arguably misleading, if the Macrohard rumors are material. Macrohard’s entry into the market is a future event that may or may not occur. Therefore, the Basic probability and magnitude test must be applied. The probability that the event will occur must be balanced with the magnitude of the effect on Linkcyst if it does occur. The magnitude here could be large, but that’s not totally clear. This product is responsible for 1/3 of Linkcyst’s revenue and income, and the entry of a huge, cash-rich company like Macrohard could have a big effect on both Linkcyst’s market share and its profits. On the other hand, Macrohard has never made computer hardware and it’s not clear that they will succeed even with a lot of money. The probability is relatively minor, at least based on the information Linkcyst currently has. Macrohard has not announced any plans, nor has the press reported any such plans. Linkcyst has no reliable information that the market entry will occur, just unconfirmed rumors. Given the weakness of this information, the probability that it will happen must be discounted. A low probability by itself does not keep something from being material, if the magnitude is high enough. It’s unclear how any given court might balance these, but it seems unlikely that a court would require Linkcyst to report unsubstantiated rumors, without more. That in itself could be misleading. Therefore, it is unlikely a court would find the omission of these rumors materially misleading.