Conscience of Memphis for Forty Years, 1968 - 2010

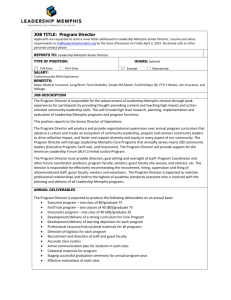

advertisement