Her life and her music

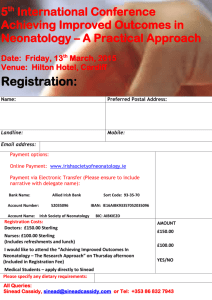

advertisement