Logical Fallacies

advertisement

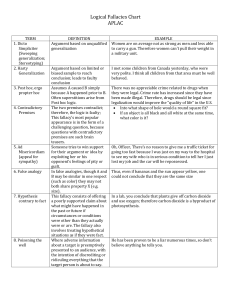

Logical Fallacies If you want to maintain your ethos and appear logical, you need to avoid logical fallacies. These errors in reasoning, if noticed, can cause your audience to suspect your assertion and your support for it. You will need to know these fallacies for a quiz. You will also want to watch for them during our class debates. In addition, they could prove helpful for the AP test. The most important lesson, however, to apply to the AP test is to recognize unsound logic—even if you are not able to retain the name of that particular fallacy. “The jawbone of an ass is just as dangerous a weapon today as in Sampson’s time.” —Richard Nixon Note that some of the statements given as fallacies may be true, but they do not provide enough logic or connection to prove the truth. They are not currently functioning as sound reasoning or developed, logical arguments. Also, the examples given as fallacies reflect many different opinions, and I am not trying to suggest any political/moral truth due to the particular examples selected. Note: Rather than providing an alphabetical list of fallacies, I have “chunked” them based on meaning. Source Note: Much of the info. and wording below comes from various sources, including McGraw-Hill’s 2004 5 Steps to a 5: Writing the AP English Essay (pgs. 69-70); Essentials of Speech Communication (pgs. 188-89); http://www.livestrong.com/article/14725-watchout-for-these-common-fallacies/; http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/mathew/logic.html; and Wikipedia’s articles on Propaganda and Persuasion. Handout put together by Shauna McPherson (and TAs), Lone Peak High School. Tier 1 You are required to read and memorize the following fallacies. They may appear on the quiz (with a word bank). Some have been known to appear on the AP test by name. However, they do not often show up on the test; they are mostly helpful in aiding students to distinguish between good logic and manipulation/over-reliance on emotion. The ideas of logical fallacies—whether you can use the exact name or not—may also help you on the essay portion of the AP test. Note: some of the fallacies are known by many different names, including the Latin version as well as English. In some cases, I have bolded the particular title used on the quiz. (In the cases where no one term is bolded, I may offer additional help later.) Non Sequitur: (Latin phrase for “does not follow”). This is an argument where the conclusion does not follow from the premise. This fallacy appears in political speeches and advertising with great frequency. For example: A waterfall in the background and a beautiful girl in the foreground have nothing to do with an automobile's performance. In another example: “Tens of thousands of Americans have seen lights in the night sky which they could not identify. The existence of life on other planets is fast becoming certainty!” (Ex 3: Jesse drives a Mercedes. He must have a great deal of money and live in a mansion. Ex 4: Dr. X is being sued. He must be a terrible doctor. Ex. 5: I saw some suspiciouslooking people in this neighborhood last night. This must be a dangerous neighborhood.) Note that sometimes the conclusion could be true—if more clues/data added up to it, but based on the one item, the conclusion seems to come out of nowhere. (Note: Colloquially, “non sequiturs” can refer to a random statement that someone—such as a character in a movie—says that leaves people laughing and scratching their head, wondering, “Where did that come from?”) Here’s a few things people have said or written in my class that I would call non sequiturs (in the colloquial sense): “I can be in whatever mood I want to be because you’re sitting in my seat.” (and then: “I don’t care if what I said made sense. You’re sitting in my seat, so it doesn’t matter.”) “Although players had shaved legs, the team unity at the State Meet was high.” “Why are there three girls’ choice dances in a row?” “Because the girls soccer field needs to be re-done.” Transfer: This fallacy is also known as association; this is a technique that involves projecting the positive or negative qualities of one person, entity, object, or value onto another to make the second more acceptable or to discredit it. It evokes an emotional response. Often highly visual, this technique sometimes utilizes symbols superimposed over other visual images. These symbols may be used in place of words; for example, placing swastikas on or around a picture of an opponent in order to associate the opponent with Nazism. Transfer makes an illogical (or stretched/distorted) connection between unrelated things; for example, if politics is corrupt, this candidate also is corrupt. Another example: Transfer is used when a soda ad includes a party or an attractive woman: it suggests that there is some kind of causal connection between drinking the soda and having a good time or attracting girls, without ever directly proving the logic of such. Note: The following four fallacies are quite similar. Begging the Question: An argument in which the conclusion is implied or already assumed in the premises. Basically, the writer assumes something in his assertion/premise that really needs to be proved. (Ex. 1: All good citizens know the Constitution’s Bill of Rights. Therefore, a test on the Bill of Rights should be given to all those registering to vote. Ex. 2: A good Christian would definitely support the such-and-such act, which bans international prostitution. Therefore, so-and-so who is arguing for it must not be Christian. Ex. 3: “Our ineffective mayor should be replaced.”) Circular Reasoning: This mistake in logic restates the premise rather than giving a reason for holding that premise. (Ex. 1: Science should be required of all students because all students need to learn science. Ex. 2: Of course the Bible is the word of God. Why? Because God says so in the Bible. Ex. 3: Conversation in Fletch that goes something like this: “Who are you?” “I’m Frieda’s boss.” “Who’s Frieda?” “She’s my secretary.”) Often, the proposition is rephrased so that the fallacy appears to be a valid argument. For example: “Homosexuals must not be allowed to hold government office. Hence any government official who is revealed to be a homosexual will lose his job. Therefore homosexuals will do anything to hide their secret, and will be open to blackmail. Therefore homosexuals cannot be allowed to hold government office.” Note that the argument is entirely circular; the premise is the same as the conclusion. An argument like the above supposedly has actually been cited as the reason for the British Secret Services' official ban on homosexual employees. (Note: I’d say this particular example could be categorized as false premise or begging the question as well.) Circular Definition: The definition includes the term being defined as a part of the definition. Example: “A book is pornographic if and only if it contains pornography.” (We would need to know what pornography is in order to tell whether a book is pornographic.) False Premise: A speaker begins with a false assumption that is assumed true. Ex. 1: “All other leading antacid remedies take 20 minutes to provide relief.” (If some of the competitors take less than 20 minutes to work, the example would be a false premise) Ex. 2: “Because Ms. McPherson is the worst teacher in the school, she should be fired.” (Understood premise of “The worst teachers should be fired”; hopefully false premise that Ms. M is the worst teacher). Ex. 3: Because you are in AP, this work must come easy for you. (Understood—and likely false—premise that hard/AP work is easy for advanced students) Note: The following three fallacies are quite similar. Attacking the Person / Ad hominem: (Latin phrase for “argue against the man”) This technique attacks the person rather than his/her argument or the issue under discussion. (Ex. 1: We all know that Brady was forced to leave college. How can we trust his company with our investments? Ex. 2: “You claim that atheists can be moral—yet I happen to know that you abandoned your wife and children.”) This is a fallacy because the truth of an assertion doesn't depend on the virtues of the person asserting it. A less blatant argumentum ad hominem is to reject a proposition based on the fact that it was also asserted by some other easily criticized person—could also call this Reductio ad Hitlerum. For example: “Therefore we should close down the church? Hitler and Stalin would have agreed with you.” (Note: It’s not always invalid to refer to the circumstances of an individual who is making a claim. If someone is a known perjurer or liar, that fact will reduce their credibility as a witness. It won’t, however, prove that their testimony is false concerning whatever matter is under discussion. It also won’t alter the soundness of any logical arguments they may make.) Obtain Disapproval or Reductio ad Hitlerum: This technique is used to persuade a target audience to disapprove of an action or idea by suggesting that the idea is popular with groups hated, feared, or held in contempt by the target audience. Thus, if a group which supports a certain policy is led to believe that undesirable, subversive, or contemptible people support the same policy, then the members of the group may decide to change their original position. (Ex. 1 A couple years ago in Utah, some who argued for Proposition 1 charged that those against it included the liberal NEA and Hillary Clinton.) Distraction by Nationalism: A variant on the traditional ad hominem and bandwagon fallacies applied to entire countries. The method is to discredit opposing arguments by appealing to nationalistic pride or memory of past accomplishments, or appealing to fear of dislike of a specific country, or of foreigners in general. It can be very powerful as it discredits foreign journalists (the ones that are least easily manipulated by domestic political or corporate interests). Example: “The only criticisms of this trade proposal come from the United States. But we all know that Americans are arrogant and uneducated, so their complaints are irrelevant.” Straw Man argument: This fallacy occurs when you misrepresent (or distort) someone else’s position so that it can be attacked more easily, knock down that misrepresented position, then conclude that the original position has been demolished. Or, Straw man is also explained as putting an opponent’s weak argument with his stronger arguments and then suggesting that when you’ve overcome the weak argument, you’ve overcome the opponents’ arguments as a whole. Example: “Those who favor guncontrol legislation just want to take all guns away from responsible citizens and put them into the hands of the criminals.” Ex. 2: Grouping all those opposed to the 2003 invasion of Iraq as “pacifists” allows the speaker to refute the group by arguing for war in general. Likewise, someone might call those who are for the war “warmongers” or “lackeys of the United States.” Note: The next two fallacies are quite similar. Hasty generalization: A person who makes a hasty generalization forms a general rule by examining only a few specific cases, which aren’t necessarily representative of all cases. Basically, the evidence is insufficient to warrant the conclusion being applied to a larger population. (Ex. 1: The well-known computer expert found a virus in his own PC. All computers must be contaminated with this virus. Ex. 2: Utah county high schools have had a rise with gang violence, so this must be a rising problem for all of Utah. Ex. 3: Obama changed his mind on how long the troops need to stay in Irag; therefore, we can’t trust our politicians—they never stick to what they originally say they will do. Ex. 4: “Jim Bakker was an insincere Christian. Therefore all Christians are insincere.”) Overgeneralization or False Generalization or Dicto Simpliciter or Sweeping Generalizations: (Stereotyping) The writer/speaker draws a conclusion about a large number of people, ideas, things, etc. based on very limited evidence. Any statement assuming all members of an ethnic, religious, or political group are all the same in all or most respects is false. (Ex. 1: All members of the Wooden Peg Club are not to be trusted. Ex. 2: Whites are well-off so they shouldn’t be in the pool for a scholarship for those who are needy or who have overcome challenges.) Words such as never, always, all, every, everyone, everywhere, no one are usually indicative of overgeneralization. It’s best to use and to look for qualifiers (some, seem, appear, often, perhaps, frequently, etc.), which indicate that the writer has an awareness of the complexities of the topic or group under discussion. (However, in writing an analysis, don’t use too many qualifiers, such as “seems” a lot—go ahead and stick your neck out, particularly if you’re pretty sure.) Another definition says that oversimplification occurs when favorable generalities are used to provide simple answers to complex, social, political, economic, or military problems. This is also sometimes called glittering generalities (See below.). A sweeping generalization occurs when a general rule is applied to a particular situation, but the features of that particular situation mean the rule is inapplicable. It's the error made when you go from the general to the specific. For example: “Christians generally dislike atheists. You are a Christian, so you must dislike atheists.” (Note: If you felt the first sentence was erroneous, you could also call this a false premise fallacy.) Note: The next five fallacies are quite similar. Glittering generalities: Oversimplification/favorable generalities are used to provide simple answers to complex social, political, economic, or military problems. The speaker/writer uses clichés; makes broad, sweeping, positive statements with little or no substance; or otherwise tries to make the audience accept something by associating it with other things that are values. Another explanation says: glittering generalities are “emotionally appealing words applied to a product or idea, but which present no concrete argument or analysis.” (Ex. 1: “Good citizens will support new housing developments in our communities.” Ex. 2: “Ford has a better idea.”) Virtue words: These are words in the value system of the target audience which tend to produce a positive image when attached to a person or issue. “Peace,” “happiness,” “security,” “wise leadership,” and “freedom,” are virtue words. See Transfer. (Ex. 1: A speech mentions phrases/words like “justice for our children, peace in our lands, virtue in our hearts,” etc.) Name Calling, Stereotyping, or Labeling. A speaker uses emotionally charged, negative terms for a group or idea, without providing proof or examining the real issues. For example, calling someone a “loser” or a “racist” is meant to turn people against him or her. This technique attempts to arouse prejudices in an audience by labeling the object of the propaganda campaign as something the target audience fears, hates, or finds undesirable. For instance, reporting on a foreign country or social group may focus on the stereotypical traits that the reader expects, even though they are far from being representative of the whole country or group; such reporting often focuses on the anecdotal. Slanting: This is a form of misrepresentation in which a statement is made which may be true, but the phrasing, connotations of words, or emphases are manipulative. For example: “I can’t believe how much money is being poured into the space program” (suggesting that “poured” means heedless and unnecessary spending). Complex question / Loaded question / Fallacy of interrogation / Fallacy of presupposition: This is the interrogative form of Begging the Question. One example is the classic loaded question: “Have you stopped beating your wife?” The question presupposes a definite answer to another question which has not even been asked. This trick is often used by lawyers in cross-examination, when they ask questions like: "Where did you hide the money you stole?” Similarly, politicians often ask loaded questions such as: “Does the Chancellor plan offer two more years of ruinous privatization?” or “How long with this EU interference in our affairs be allowed to continue?” (Anecdotal Evidence often functions as a sub-category of the hasty generalization fallacy.) Anecdotal Evidence: One of the simplest fallacies is to rely on anecdotal evidence. For example: “There's abundant proof that God exists and is still performing miracles today. Just last week I read about a girl who was dying of cancer. Her whole family went to church and prayed for her, and she was cured.” It is quite valid to use personal experience to illustrate a point; but such anecdotes do not act as proof by themselves. For example, your friend may say he met Elvis in the supermarket, but those who haven’t had the same experience will require more than your friend’s anecdotal evidence to convince them. Anecdotal evidence can seem very compelling, especially if the audience wants to believe it. This is part of the explanation for urban legends; stories which are verifiably false have been known to circulate as anecdotes for years. Note: When a speaker/writer tries to use an anecdote alone to prove a point, it is also a hasty generalization (perhaps such and such did occur in one person’s experience, but that experience alone is likely not enough evidence to generalize as a rule). Note: Anecdotes are often effective in creating pathos or helping a speaker connect with the audience, but they are not good at creating a foundation of logos—although, an anecdote may be one building block in creating evidence. Note: The next three fallacies are quite similar—as well as similar to the hasty generalization. False Cause (or Non Causa Pro Causa): This fallacy occurs when something is identified as the cause of an event, but it has not actually been shown to be the cause. For example: “I took an aspirin and prayed to God, and my headache disappeared. So God cured me of the headache.” Two specific forms of this fallacy include the cum hoc ergo propter hoc and post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacies, which follow. Correlation vs. Cause or Cum Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc: The fallacy, a form of hasty generalization or false cause, asserts that because two events occur together, they must be causally related. It’s a fallacy because it ignores other factors that may be the cause(s) of the events. “Literacy rates have steadily declined since the advent of television. Clearly television viewing impedes learning.” (Possibly a third factor has caused literary rates to decline.) Post hoc (full name is Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, but most just call Post hoc): A form of a hasty generalization or false cause in which it is inferred that because one event followed another it is necessarily caused by that event. Example: Mary joined our class and the next week we all did poorly on the quiz. It must be her fault. Or: “The Soviet Union collapsed after instituting state atheism. Therefore we must avoid atheism for the same reasons.” Basically, this fallacy cites an unrelated (or, at least, not proved as related) event that occurred earlier as the cause of a current situation. (Ex. 1: I had an argument with my best friend the night before my driver’s test; therefore, I blame her for my failure. Ex. 2: Ever since Bush came into office, our economy has tanked; therefore, it’s Bush’s fault.) Eithor/or (also called Black-and-White and False Dichotomy or False Dilemma): The writer asserts that there are only two (usually extreme) possibilities, when, in reality, there are more. (Ex. 1: Tomorrow is my chemistry final; therefore, I must study all night, or I will fail the course. Ex. 2: You can have an unhealthy, unreliable engine, or you can use Brand X oil. Ex. 3: “Either man was created, as the Bible tells us, or he evolved from inanimate chemicals by pure random chance, as scientists tell us. The latter is incredibly unlikely, so . . . ”) Slippery Slope: This line of reasoning assumes that if one action is taken, it will lead to inevitable and extreme consequences. There is no gray area or middle ground. This argument argues for (or against) the first step because, if you take the first step, you will inevitably follow through to the last. For example: “If one Aggie sits down during a football game, soon everyone will; then all our traditions will be ruined.” Ex. 2: “We can’t allow students any voice in decision-making on campus; if we do, it won’t be long before they are in total control.” Ex. 3: “If we legalize marijuana, then more people would start to take crack and heroin, and we’d have to legalize those too. Before long we’d have a nation full of drug-addicts on welfare. Therefore we cannot legalize marijuana.” Ex. 4: If we allow PDA in the halls, next thing we know tons of girls will be pregnant and then who will be working our stores and running our economy? (This last one is pretty similar to what a student wrote in a paper for AP. It is an example of slippery slope as well as non sequitur.) Plurium Interrogationum / Many Questions: This fallacy occurs when someone demands a simple (or simplistic) answer to a complex question. For example: “Are higher taxes an impediment to business or not? Yes or no?” Red Herring: This fallacy introduces an irrelevant issue into a discussion as a diversionary tactic. It takes people off the issue at hand; it is beside the point. (It might be related to what’s being discussed, but it’s not the exact issue on the table.) Example: Many people say that engineers need more practice in writing, but I would like to remind them how difficult it is to master all the math and drawing skills that an engineer requires. Ex. 2: “You may claim that the death penalty is an ineffective deterrent against crime—but what about the victims of crime? How do you think surviving family members feel when they see the man who murdered their son kept in prison at their expense? Is it right that they should pay for their son’s murderer to be fed and housed?” Note: The next two fallacies are quite similar. Appeal to Authority: Appeals to authority cite prominent figures to support a position, idea, argument, or course of action. Oftentimes it is an authority in one field who is speaking out of his field. For example: “Isaac Newton was a genius and he believed in God.” Other examples include sports stars selling cars or hamburgers, or the actor on a TV commercial that says, “I'm not a doctor, but I play one on TV.” This line of argument isn't always completely bogus when used in an inductive argument; for example, it may be relevant to refer to a widely-regarded authority in a particular field, if you're discussing that subject. For example, the following would be pretty good as a piece of evidence: “Hawking has concluded that black holes give off radiation.” (Hawking is a renowned physicist, and so his opinion seems relevant.) Unrelated testimonials: Authorities in one field are used to endorse a product or an idea that they lack expertise about. (Ex. 1: A famous basketball player endorses a political candidate.) Appeal to Emotion: In this fallacy, the arguer uses emotional appeals rather than logical reasons to persuade the listener. The fallacy can appeal to various emotions, including pride, pity, fear, hate, vanity, or sympathy. Generally, the issue is oversimplified to the advantage of the arguer. Appeal to fear: Appeals to fear seek to build support by instilling anxieties and panic in the general population. This fallacy is often used by politicians, and can be summarized as “might makes right.” For example: “In any case, I know your phone number and I know where you live. Have I mentioned I am licensed to carry concealed weapons?” (Note that it doesn’t have to be an implied threat from the speaker; it can merely motivate by causing fear—fear of foreigners, fear of another Great Depression, etc.) Argumentum ad Misericordiam (Appeal to pity; Special pleading): The fallacy is committed when someone appeals to pity for the sake of getting a conclusion accepted. For example: “I did not murder my mother and father with an axe! Please don't find me guilty; I'm suffering enough through being an orphan.” Note: The next three fallacies are quite similar. Argument from Analogy or False Analogy: An unsound form of inductive argument in which an argument is based completely or relies heavily on analogy to prove its point. Example: “This must be a great car, for, like the finest watches in the world, it was made in Switzerland.” Ex. 2: “Saddam Hussein had killed quite a few people. He was another Hitler and if we hadn’t have killed him at this point, just imagine what he might have done next.” False Assumption: The assumption that because two things are alike in some ways, they must be in other ways. Natural Law fallacy / Appeal to Nature (related to false analogy): This is a common fallacy in political arguments. One version consists of drawing an analogy between a particular conclusion, and some aspect of the natural world—and then stating that the conclusion is inevitable, because the natural world is similar: “The natural world is characterized by competition; animals struggle against each other for ownership of limited natural resources. Capitalism, the competitive struggle for ownership of capital, is simply an inevitable part of human nature. It’s how the natural world works.” Another form of appeal to nature is to argue that because human beings are products of the natural world, we must mimic behavior seen in the natural world, and that to do otherwise is “unnatural.” Card-stacking. The speaker mentions only the facts that will build the best case for his or her argument, ignoring other factors or evidence. For example, an advertisement for a sale on spring clothing doesn’t mention that only 20 items are on sale, making people believe everything in the whole store in on sale. Tu quoque or Two Wrongs Make a Right: This fallacy is committed when we try to justify an apparently wrong action by charges of a similar wrong. The underlying assumption is that if they do it, then we can do it too and are somehow justified. Example: Supporters of apartheid are often guilty of this error in reasoning. They point to U.S. practices of slavery to justify their system. Note: The next two fallacies are quite similar. Appeal to Ignorance / Ad Ignorantium. This occurs when it’s argued that something must be true, simply because it hasn't been proved false. Or, vice versa: If you can’t prove that something is true then it must be false. Example: You can't prove there isn’t a Loch Ness Monster, so there must be one. (Note that this isn’t the same as assuming something is false until it has been proved true. In law, for example, you’re generally assumed innocent until proven guilty.) Here are a couple of examples: Ex. 1: “Of course the Bible is true. Nobody can prove otherwise.” Ex. 2: “Of course telepathy and other psychic phenomena do not exist. Nobody has shown any proof that they are real.” See also Shifting the Burden of Proof. Shifting the Burden of Proof: The burden of proof is always on the person asserting something. Shifting the burden of proof, a special case of Argumentum ad Ignorantiam, is the fallacy of putting the burden of proof on the person who denies or questions the assertion. The source of the fallacy is the assumption that something is true unless proven otherwise. Ex. 1: “Okay, so if you don't think the grey aliens have gained control of the U.S. government, can you prove it?” Equivocation: An assertion that falsely relies on the use of a term in two different senses. The arguer uses the ambiguous nature of a word or phrase to shift the meaning in such a way as to make the reason offered appear more convincing. Example: An ad from a sugar company says “Sugar is an essential component of the body, a key material in all sorts of metabolic processes, so buy some P&R sugar today.” The word “sugar” is being used with two definitions that the ad does not acknowledge. Ex. 2: “What could be more affordable than free software? But to make sure that it remains free, that users can do what they like with it, we must place a license on it to make sure that it will always be freely redistributable.” One way to avoid this fallacy is to choose your terminology carefully before beginning the argument, and avoid/take care with words like “free” which have many meanings. (Or define/be clear with your terms.) Note: The following six fallacies are quite similar/related. (For now, studying the common idea of these fallacies is more important than distinguishing between them. For the quiz, I will let you know which of the following six you should know well.) Common Belief: This fallacy is committed when we assert a statement to be true on the evidence that many other people allegedly believe it. Being widely believed is not proof or evidence of the truth. Example: “Of course Nixon was guilty in Watergate. Everybody knows that.” Past Belief or Appeal to Tradition/Argumentum ad Antiquitatem (a form of the Common Belief fallacy): The same error in reasoning is committed except the claim is for belief or support in the past. In other words, asserting that something is good or bad simply because it’s old, or because “that’s the way it’s always been.” Example: “Everyone knows that the Earth is flat, so why do you persist in your outlandish claims?” This is the opposite of the Argumentum ad Novitatem fallacy, which suggests something is better just because it is newer. Example of Appeal to Tradition: “For thousands of years Christians have believed in Jesus Christ. Christianity must be true, to have persisted so long even in the face of persecution.” Ex. of Argumentum ad Novitatem: “BeOS is a far better choice of operating system than OpenStep, as it has a much newer design.” Common Man: The “plain folks” or “common man” approach attempts to convince the audience that the propagandist’s positions reflect the common sense of people. It is designed to win the confidence of the audience by communication in the common manner and style of the target audience. Propagandists use ordinary language and mannerisms (and clothe their message in face-to-face and audiovisual communications) in attempting to identify their point of view with that of the average person. Bandwagon Appeals: This form of fallacy/persuasion attempts to persuade the target audience to join in and take the course of action that “everyone else is taking.” (Similar to Argumentum ad Numerum.) Tier 2 You are required to read these fallacies and try to digest them, but they will not appear on the quiz and they likely would not appear on the AP test by name. Argumentum ad Numerum: This fallacy is closely related to the argumentum ad populum. It consists of asserting that the more people who support or believe a proposition, the likelier that that proposition is correct. For example: “The vast majority of people in this country believe that capital punishment has a noticeable deterrent effect. To suggest that it doesn't in the face of so much evidence is ridiculous.” Ex. 2: “All I'm saying is that thousands of people believe in pyramid power, so there must be something to it.” Argumentum ad Populum (Appeal to the people or gallery): You commit this fallacy if you attempt to win acceptance of an assertion by appealing to a large group of people. This form of fallacy is often characterized by emotive language. For example: “Pornography must be banned. It is violence against women.” (Note that the example before might be turned more logical if it proved harm against women and showed a detrimental effect on women, but, currently, it merely appeals to what people want to hear, or to a general value/superstition.) Ex. 2: “For thousands of years people have believed in Jesus and the Bible. This belief has had a great impact on their lives. What more evidence do you need that Jesus was the Son of God? Are you trying to tell those people that they are all mistaken fools?” Argumentum ad Lazarum: This fallacy assumes that someone poor is sounder or more virtuous than someone who’s wealthier. This fallacy is the opposite of the Argumentum ad Crumenam. For example: “Monks are more likely to possess insight into the meaning of life, as they have given up the distractions of wealth.” Argumentum ad Crumenam: The fallacy of believing that money is a criterion of correctness; that those with more money are more likely to be right. The opposite of Argumentum ad Lazarum. An example of Argumentum ad Crumenam: "Microsoft software is undoubtedly superior; why else would Bill Gates have gotten so rich?" Argumentum ad Nauseam: Tireless repetition. An idea, especially a slogan, once repeated enough times, is taken as the truth. Used especially by the media. Employs constant repetition in asserting something, or saying the same thing over and over again, to try and wear down the audience/make you convinced. Amphiboly: A fallacy of syntactical ambiguity deliberately misusing implications. Example: “Three out of four doctors recommend this type of pain relief!” The implied assertion here is that “three out of four” means seventy-five percent of all doctors and that “this type of pain relief” means this particular pain reliever. In actuality, they might have only polled four doctors, or they might have polled twenty and then chosen four out of those twenty to act as their sample size.