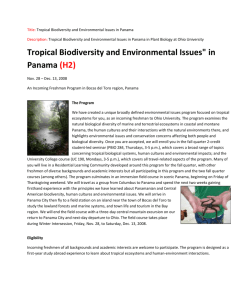

Biodiversity in Panama - Global Environment Facility

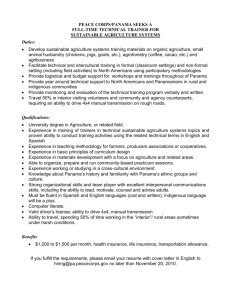

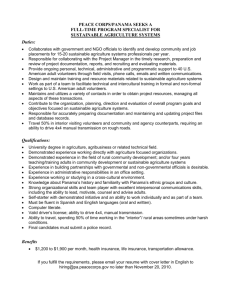

advertisement