Family-centred, person-centred planning

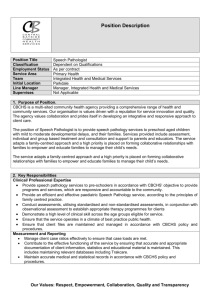

advertisement