OSTRAKON Part Five: Letters

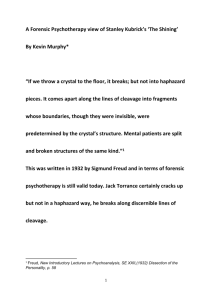

advertisement