New Deal Outline - U-System

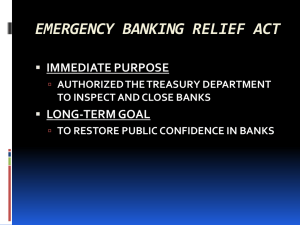

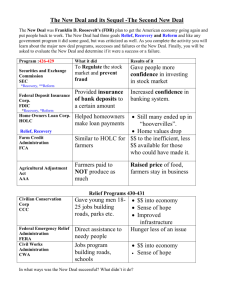

advertisement