damien hirst`s death drive

advertisement

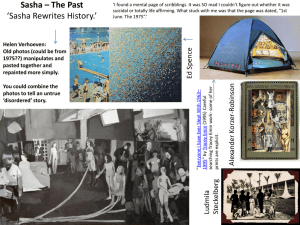

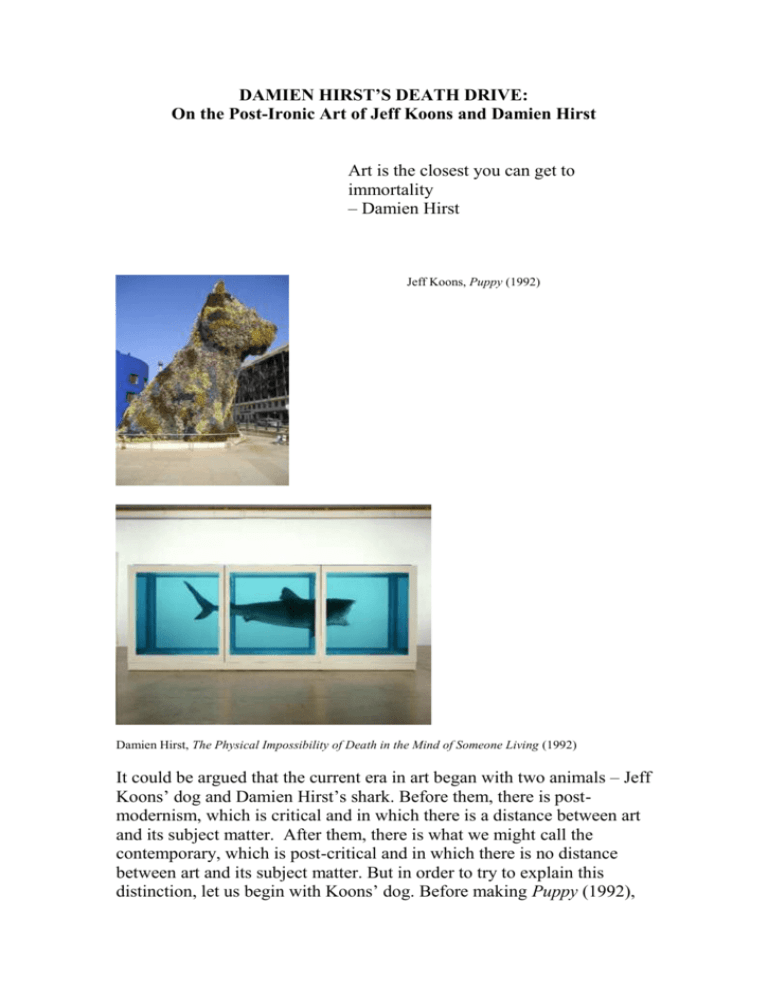

DAMIEN HIRST’S DEATH DRIVE: On the Post-Ironic Art of Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst Art is the closest you can get to immortality – Damien Hirst Jeff Koons, Puppy (1992) Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1992) It could be argued that the current era in art began with two animals – Jeff Koons’ dog and Damien Hirst’s shark. Before them, there is postmodernism, which is critical and in which there is a distance between art and its subject matter. After them, there is what we might call the contemporary, which is post-critical and in which there is no distance between art and its subject matter. But in order to try to explain this distinction, let us begin with Koons’ dog. Before making Puppy (1992), Koons was best known for a series of works featuring basketballs, bar equipment and vacuum cleaners. As one of the members of the “simulationist” art movement of the 1980s, his work was understood to be based on the French sociologist Jean Baudrillard’s critique of the “sign”. Thus Haim Steinbach’s dolls and ceramics mounted on walls or Koons’ vacuum cleaners housed in glass vitrines were spoken of by critics as an analysis of the “charms with which Madison Avenue tempts the American consumer”.1 In many ways, of course, these simulationists were merely updating Warhol’s original parody of consumerism in his Brillo Boxes (1963) and Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). The absurdly detailed descriptions of the various vacuum cleaners in Koons’ The New (1980-6) – New Hoover Deluxe Shampoo Polisher, New Hoover Convertible and New Shelton Wet/Dry Doubledecker – remind us of the equally unnecessary proliferation of flavours in Warhol’s Campbell Soup Cans. Of course, the variety of different soups in Warhol and of vacuum cleaners in Koons is intended as a commentary on the unchecked production of marginally differentiated consumer items in advanced capitalism. After all, who could really taste the difference between the Green and Split Pea soups in the Campbell’s Soup range? And who would really need a New Hoover Convertible as opposed to a New Hoover Deluxe Shampoo Polisher when cleaning their house? But, at the same time, both series are also parodies of the same minute differences being given such consequence in the evaluation of art. For are not the aesthetic discriminations connoisseurs make between seemingly identical works of art in the end just another form of product differentiation? Indeed, the ultimate point made by both Warhol and Koons is the absolute homology between the art market and the more general market: aesthetic taste is reduced to consumer preference. But what, then, of the work of art that points this out? Might it not, by making clear its own implication within the system of commodities, somehow escape it? Might not the work of art be an exception to that system of signs it otherwise admits itself as belonging to? These questions inaugurate the long agony of post-modernism, which consists of the work of art being at once inside and outside of the phenomenon it is analysing.2 Thus one could no sooner say of Warhol that his work is a cynical attempt to sell art as a commodity than it would be seen to be about the attempt to sell art as a commodity. We could no sooner say of Koons that his work evidences the collapse of all aesthetic distinctions than it would be seen to be about the collapse of all aesthetic distinctions. And this logic runs all the way through that generation of artists like Koons who first came to prominence in the 1980s. We would say, for example, of the photographs of Cindy Sherman that they do not replay the stereotypes of women in our culture but critically reframe them. We would say of the appropriations of Sherrie Levine that they are not part of the mythology of avant-gardism but distance us from it. We would say of the paintings of Julian Schnabel that they do not repeat the expressivist fallacy but undermine it. It is the logic of a generalised irony, in which every aspect of the work of art (its subject matter, technique, authorship) is treated not directly but as a kind of readymade, able to be grasped from the beginning only through its reception and elaboration within the history of art. Koons’ Puppy breaks with all of this. The remarkable thing about it is that, against all that was happening in the art world at the time, its content and form were meant sincerely, with no attempt at authorial distance. It is this that Koons himself emphasises about the work: “Puppy communicates love, warmth and happiness to everyone. I created a contemporary Sacred Heart of Jesus”.3 But it is just this lack of irony that makes it so hard for art critics, whose only mode of meaning in art is a kind of self-reflexive criticality, to take the work seriously. As one prominent commentator has been quoted as saying: “I find his work repulsive. It has no message”.4 And this absence of irony is also to be seen in the series Koons completed the same year as Puppy, Made in Heaven (1989-92). In Made in Heaven, Koons enacts a number of pornographic tableaux with his then-wife Ilona Staller, culminating as is typical of the genre with images of Koons’ penetration and ejaculation. What we might say Koons stages there is the overcoming of irony, for what defines hard-core pornography is that there is no faking it. In theory at least, male erection and ejaculation cannot be done in two minds, with that split or ambiguous intentionality that characterises post-modernism. What we see with Koons’ orgasm, as it were, is the pure expression of authorial subjectivity, with no aesthetic or conceptual second thoughts behind it. Damien Hirst, A Thousand Years (1990) It is, to start with, this emphasis on the bodily that Hirst shares with Koons. Like Koons, what Hirst pledges himself to over and over in his work is the overcoming of the de facto state of all art today as readymade. His real influences are not Duchamp and Warhol, but Beuys and Bacon. Take, for instance, the work that first brought Hirst to critical attention, A Thousand Years (1990). The installation is like Bacon, not only in the concentrating power of the glass vitrines in which its drama takes place, but also in its realisation of one of Bacon’s stated ambitions for his own work. In his original 1975 interviews with David Sylvester, Bacon reveals that one of the aims of his work is to create something that “leads a life completely of its own”.5 It is this idea of a work of art always being in transformation that explains one of Bacon’s better-known desires for his painting: that it not be about anything – which he condemns as “conveying through illustrating” – but that it actually be that thing – which he describes as coming across “directly onto the nervous system”.6 And it is this effect of immediacy that Hirst seeks to bring about with the rotting cow’s head, flies, insect-o-cutor and escape hatch of A Thousand Years: an autonomous work of art that, once set in motion, remains out of the artist’s control. It would be a work that not so much imitated nature as was nature. To repeat a distinction much used in the history of philosophy, it would be nature as process (natura naturans) and not nature as finished product (natura naturata). Indeed, it would be in this way too that Hirst would complete the ambition of Beuys (a Frankenstein-like artist, if ever there was one): that of creating “artificial” life through the putting together of different organic materials. In fact, considered more closely, Koons’ and Hirst’s oeuvres reveals themselves as opposites. In Koons, we have the desire for total authorial control over the work and the direct connection of the artist with his audience. This would be evidenced by the seamless finish of his sculptures and the well-known story of him obsessively polishing the glass vitrines of his vacuum cleaners every morning before the gallery opened to remove all human traces. In Hirst, it is not so much the artist as the work of art that communicates with the audience, and the final form of his various objects is open, provisional, contingent (typical of Hirst’s entire aesthetic in this regard would be the Spin Paintings of 1995). Nevertheless, both artists do thereby break with the irony of postmodernism. Their work is not both inside and outside of what it represents. There is no problem of authorial intentionality, insofar as it is not about our interpretation of it. We see this in Hirst’s next major work, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991). It is, of course, tempting to see the piece as merely the latest in a long line of readymades throughout the history of art, asking the question of what it means to put a shark in an art gallery. But this shark goes against the logic of the readymade on a number of levels. It is not the contingent act of artistic selection that makes the work, like selecting one out of a series of otherwise identical urinals. Rather, the shark is a unique wild animal that is not selected but captured, and that in our culture functions as the stuff of our worst nightmares, the very image of our own individual and unsubstitutable death. In a way, like Koons’ use of hardcore pornography, Hirst here through the sheer physical presence of the shark seeks to overcome all aesthetic, historical and conceptual mediation and confront us directly with the thing itself. The work is not about the gesture of putting a shark in an art gallery. On the contrary, Hirst uses the gallery as an opportunity to confront us with this shark. Damien Hirst, Mother and Child, Divided (1993) But we might go further with The Physical Impossibility of Death. For what connection might we draw between it and such early pieces as A Thousand Years and the butterfly painting In and Out of Love (1991)? And what would it and the famous vivisected animals and the later religiously themed series like Romance in the Age of Uncertainty (2003) and New Religion (2005) have in common? As we say, the shark is for us the very image of death. It speaks not just of death’s subjective impossibility for us who are alive, but also of its objective inevitability, the fact that we all will die. And this is to say that, if the shark is a figure of death, it is even more the embodiment of the death drive, that which cannot be killed. (The paradox of Hirst’s work is that, even though the shark is motionless and therefore dead – for a shark cannot breath if it does not constantly move forward – it nevertheless appears so alive and about to bite.) The death drive, in psychoanalysis, refers not so much to any tendency towards the end of things as to its opposite: a kind of undead excess, that which takes life beyond itself. It is what in the human cannot be reduced to the biological cycle of birth and death: it is wasteful and destructive but also spiritual and transcendent. It is at once the lowest and the highest of human impulses.7 And it is precisely this – this excess that stops life just being life – that Hirst is obsessively getting at in his work. It is this death drive that is not only the immortality that Hirst seeks to attain through his work but the immortality – again, the Bacon theme – that Hirst attempts to create in his works. It is from the perspective of the death drive that we might put together, for example, Hirst’s series of vivisected animals like Mother and Child, Divided (1993) and This Little Piggy (1996) and the later religious works. These two series might at first appear opposed or the result of some unresolved contradiction in Hirst’s aesthetic: the former material, despiritualised, fallen, and the latter immaterial, spiritual and transcendent. But, in fact, coming after the effort to create life in A Thousand Years, the works involving the cutting-up of animals can be understood as an attempt – almost like certain scenes in Sade – to locate the soul, that “motor” of the creature not reducible to the flesh. Looking at the various bodies’ internal organs laid out before us, we are struck by the extraordinary beauty and complexity of what we see, which seems to exceed any rational accounting or explanation. But, more than this, by a kind of subtraction or reductio ad absurdum, Hirst is wanting to show that the life of an animal is not to be mistaken for anything physical. There is something there we cannot see, no matter how hard we look, like that excess brought about in those otherwise “zero sum” games of A Thousand Years and In and Out of Love. It would be the desire of the flies to escape even though they risk death in A Thousand Years and it would be the art or beauty that is left behind in In and Out of Love.8 In a piece like This Little Piggy, in which the two halves of the pig are each in their own vitrine, incessantly sliding back and forth across each other driven by an engine, there is at once an unending vivisection, a cutting up of the body into finer and finer slices, and in this motion itself a kind of inextinguishable life, almost as though the machine were being powered by something inside the pig. The paradox of the work here, as before, is that the attempt to find out where life originates necessarily misses it. Or the reduction of life to the flesh itself produces its own immaterial spirit. And it is in this light that we might think of Mother and Child, Divided as enacting a kind of virgin birth, with the mother cow able to multiply or reproduce even across glass. It is this excess too that can be seen in the butterfly wing paintings (2002-6), where the resulting patterns that are built up appear as something greater than any individual, like some unconscious evolutionary goal or some chromosomal programming that is passed on from generation to generation. And, finally, it is this death drive that is evident in Hirst’s fascination with cigarette smoking and cancer, for in both of these things there is a kind of habit or disease that will outlive its host, that is more alive than the person it occupies.9 Damien Hirst, St Sebastian, Exquisite Pain (2007) In an apparently opposed register, it is this insight into the undead nature of the death drive that allows us to understand properly such recent Hirst series as Uncertainty in the Age of Romance and Beyond Belief (2007). Crucial to the argument of Hirst’s religious works – something forgotten by all New Age and liberal Christian denominations – is that the spirit is indissociable from (the sufferings of) the flesh.10 When we look at the metal spikes driven into the heart on the altar of New Religion or the arrows in the young bull of St Sebastian, Exquisite Pain (2007), it is their suffering that we also feel in our flesh. The profound enigma of the works – again, what Bacon might mean by wishing the work to come across “directly onto the nervous system” – is that something as immaterial as pain can be transferred from body to body. There is an affect produced by looking at the suffering of the Apostles in Hirst’s Romance in the Age of Uncertainty that is the soul. In one way, as in the Bible, each prophet in Hirst’s rendering is reduced to the particular bodily mortification that they will undergo (St Thomas is speared, St Peter is crucified upside down), but what Hirst shows us is that the human can never be reduced to this. The equation he puts his faith in is that the more suffering the body undergoes the more beautiful it is, the more it is reduced to the medical or pharmacological the more its spirituality shines forth. Damien Hirst, For the Love of God (2007) This is the true “religious” dimension of Hirst’s work: that the spirit is not to be grasped outside of its corporealisation but only in and through the flesh. And this would be just as the mystery of the Incarnation tells us that God is not to be understood as some supernatural deity but only ever in the form of the man: Christ is merely that extra dimension already within the human itself. Thus the dove of the Holy Spirit in Hirst’s A Faint Hope Beyond the Fear of Death (2005) and The Incomplete Truth (2007) appears not as something noumenal or transcendent lying behind appearances, but rather as appearance itself, a momentary gathering or condensation of the atmosphere. This is why Hirst’s work constantly flirts with kitsch: because the supernumerary is never to be conceived outside of the things of this world. And it is at this point, to conclude, that we might turn to the last work of Hirst considered here: the diamond skull of For the Love of God (2007). Obviously, the first point to note is that, like Physical Impossibility, it is a work about death. The piece has been compared to Western mementi mori or vanitas paintings and to Aztec or Mexican reliquaries. The skull even has the same open eyes and terrifying grin as the shark. But, more importantly, the presence of death serves to cut off the transcendental dimension, to remind us that there is no other world than this one. And yet, as we have seen throughout, it is this cutting off of the transcendental dimension, the forgoing of any alternative to this world, that liberates another dimension here on earth.11 For, in For The Love of God, there is a miraculous and inexplicable shining forth that gives the skull a kind of life and that, while it cannot be separated from the diamonds with which it is covered, is not simply to be identified with them. It is the same surplus or surplus value at stake in the idea of Hirst selling For the Love of God for more than it cost to make (a muchpublicised fact that is very much part of the work). This excess is the art of For the Love of God – and it is the very aura that hovers immaterially over the skull like that last fading close-up of Hitchcock’s Psycho: that of the imperishable “human” that fleshes out our bones, that lives on after we do. Rex Butler Eleanor Heartney, ‘The Hot New Cool Art: Simulationism’, Art News 86, January 1987, p. 133. One of the best essays written on post-modernism is still Wolfgang Max Faust’s ‘Du haste keiner chance. Nutze sie! With It and Against It: Tendencies in Recent German Art’, Artforum, September 1981. 3 Jeff Koons, The Jeff Koons Handbook, Thames and Hudson, London, 1992, p. 144. 4 Rosalind Krauss, cited in Sylvère Lotringer, ‘Immaculate Conceptualism’, Artscribe 90, FebruaryMarch 1992, p. 24. 5 David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, Thames and Hudson, London, 1997, p. 17. 6 Ibid, p. 18. 7 We are drawing here on the notion of the death drive recently developed by Slavoj Žižek, which breaks with the biologism of Freud in his original treatment in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. For an example of Žižek’s argument, see The Sublime Object of Ideology: Enjoyment as a Political Principle (Verso, London, 1989): “‘Death drive’ is not a biological fact but a notion indicating that the human 1 2 psychic apparatus is subordinated to a blind automation of repetition beyond pleasure-seeking, selfpreservation, the accordance between man and his milieu… ‘Death drive’ cannot be reduced to an expression of alienated social conditions, there is no solution, no escape from it; the thing to do is not to ‘overcome’ it, to ‘abolish’ it, but to come to terms with it” (pp. 4-5). 8 We might ask, for instance, why Hirst calls his work A Thousand Years. The answer is that the title refers not to the eternal life cycle of flies laying eggs and hatching but rather to the imperishable desire of the flies to escape from this cycle altogether. 9 Similarly, we might think of the various Apostles being matched with a pill in New Religion: here too the “after-life” being spoken of is the addiction to these sedatives and painkillers that lives on after we do. 10 The real artistic comparison to make with Hirst would indeed be to someone like the Mel Gibson of The Passion of the Christ. 11 For an excellent essay on this notion, see Joshua Delpech-Ramey, ‘The Idol as Icon: Andy Warhol’s Material Faith’, Angelaki 12 (1), April 2007.