A Midsummer Night`s Dream | Introduction

advertisement

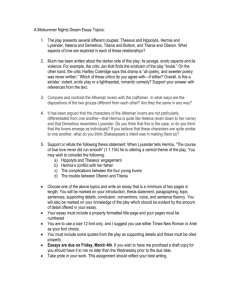

A Midsummer Night’s Dream | Introduction 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Printable Version Download PDF Cite this Page Ask a Question Tweet This Probably composed in 1595 or 1596, A Midsummer Night's Dream is one of Shakespeare's early comedies but can be distinguished from his other works in this group by describing it specifically as the Bard's original wedding play. Most scholars believe that Shakespeare wrote A Midsummer Night's Dream as a light entertainment to accompany a marriage celebration; and while the identity of the historical couple for whom it was meant has never been conclusively established, there is good textual and background evidence available to support this claim. At the same time, unlike the vast majority of his works (including all of his comedies), in concocting this story Shakespeare did not rely directly upon existing plays, narrative poetry, historical chronicles or any other primary source materials, making it a truly original piece. Most critics agree that if a youthful Shakespeare was not at his best in this play, he certainly enjoyed himself in writing it. The main plot of Midsummer is a complex contraption that involves two sets of couples (Hermia and Lysander, and Helena and Demetrius) whose romantic crosspurposes are complicated still further by their entrance into the play's fairyland woods where the King and Queen of the Fairies (Oberon and Titania) preside and the impish folk character of Puck or Robin Goodfellow plies his trade. Less subplot than a brilliant satirical device, another set of characters—Bottom the weaver and his bumptious band of "rude mechanicals"—stumble into the main doings when they go into the same enchanted woods to rehearse a play that is very loosely (and comically) based on the myth of Pyramus and Thisbe, their hilarious home-spun piece taking up Act V of Shakespeare's comedy. A Midsummer Night's Dream contains some wonderfully lyrical expressions of lighter Shakespearean themes, most notably those of love, dreams, and the stuff of both, the creative imagination itself. Indeed, close scrutiny of the text by twentieth-century critics has led to a significant upward revision in the play's status, one that overlooks the silliness of its story and concentrates upon its unique lyrical qualities. If A Midsummer Night's Dream can be said to convey a message, it is that the creative imagination is in tune with the supernatural world and is best used to confer the blessings of Nature (writ large) upon mankind and marriage. Symbol The Moon The moon represents as many different things in the play as night. Night is called "fairy time," but it’s also a time for human mourning and love-making, as well as a time for the natural world to be unleashed, with scary animals and ghosts traipsing about. As the moon presides over the night, it has as many facets as the night itself. It’s a source of light (or lack thereof) when Hermia and Lysander get lost in the woods, and it’s presented in Pyramus and Thisby as a lantern and a central part of rural folklore. The moon is also the center of learned allusions – Puck refers to the moon as the realm of that dark witchy figure Hecate, while the lovers and Oberon refer to the moon’s position as a symbol of Diana, the virgin goddess. The moon provides the light for lovers, but it also weeps at it’s own chastity, which is why dewdrops sprinkle the earth when the moon sets. This is a gorgeous idea, but the moon gets a beautiful connection to another important Shakespearean woman as well. When Oberon describes the time that Cupid’s arrows hit the pansy and turned it all magical, it’s because Cupid was aiming for a royal virgin (which we can assume is a nod to Queen Elizabeth). Oberon mentions that the moon’s virgin waves of light deterred Cupid’s arrows to protect the Virgin Queen. In this way, Diana and Elizabeth I are included together into the same holy cult of cherished chastity. Of course, the moon also seems to have some influence over the lovers. The play opens with Theseus’s lament that the moon should keep him and Hippolyta apart so long. For the older lovers, the moon is a symbol of the time that must be waited patiently. For the young lovers, though, the moon suits their tempestuousness, rather than inspiring them to virtue. The moon waxes and wanes, and in Shakespeare’s time (remember from Romeo and Juliet: "Swear not by the moon, the inconstant moon"?) it was thought of as more fickle than constant. These constant changes reflect the tendency of lovers to fall in and out of love – all lovers, from the King and Queen of the Fairies to the youthful Athenians. Nature When we first meet Puck at the beginning of the second act, he’s with a fairy out running errands for Titania, obviously tied closely to the natural world. The flowers they talk about are part of the cult of Titania – weighed down by dewdrops, the petals bow their heads to the Fairy Queen. The red spots on the flowers are rubies, presents from the fairies. Even the little sprites that attend Titania and Bottom have names that hearken back to the natural world, not any seriously magical element. In this way, natural is made magical, not by any fairy tricks, but by virtue of inherent beauty. Setting Athens in antiquity; A wood outside of Athens; During midsummer The play is set in Athens, where the rule of law is strong. The threat of death (or celibacy) that Theseus has to raise against Hermia is enough of an excuse to contrive for all four lovers to be in the wood getting their plot complications on. Here, the majority of the action takes place. As in all pastorals, the wood is the perfect space for man-made rules to get suspended: Bottom, a lowly workman, can cavort with the Queen of the Fairies, the Athenian lovers can fight and love as lovers do, and most importantly, fairy magic (not the rule of law) can reign supreme. Once everyone is back in Athens, the setting has dropped all semblance of being any kind of ancient Greek place, and seems more like a generic noble house of the Elizabethan era. The Duke and his new wife have courtly entertainments befitting contemporary Elizabethan society. (Speculation about the play places it as a piece written for some courtly wedding celebration, which would shed some light on why the customs in the play are Elizabethan.) Besides the courtly/pastoral element of the setting, the other notable setting element is the play’s timing. Shakespeare is careful to not give us an exact year, but we do know by the title that the play is set at midsummer, which marks the summer solstice, around June 21. The celebration of the summer solstice is rooted in paganism, but it survived into the JudeoChristian era with celebrations like May Day. Theseus even comes into the woods announcing that the youngsters must’ve come to "observe the rite of May," or perform the rituals associated with May Day and the celebration of spring’s approach – which, by the way, is also the time of mating and creating. This setting element influences the actions of the play in a way that’s unique even among Shakespeare’s pastorals. Many plays are concerned with marriage and fertility, but this play’s May Day setting specifically emphasizes the natural and seasonal influences on fertility and fortunes. Spring is the natural season of blossoming and fertility. Everyone seems to have decided that love also blooms in this time, which paves the way for the new Athenian residents (we’re talking about babies) that Oberon talks about at the end of the play. The natural setting is important for it’s rule relaxation, but the rituals of this particular time (and the fairies that rule over this time) influence the courtly world. Even the court must be blessed by nature in order to reap her benefits. A final word on setting: Puck ends the play asking the audience to think of the play as only a dream, which would go a long way to explain how silly, absurd and literally incredible it often is. If you wanted to, you could argue the entire play is set in a dream. Narrator Though all works of literature present the author’s point of view, they don’t all have a narrator or a narrative voice that ties together and presents the story. This particular piece of literature does not have a narrator through whose eyes or voice we learn the story. Genre Comedy, Pastoral As with many of Shakespeare’s plays, we know this one’s a comedy because it ends in marriage and, to the best of our knowledge, no one dies a horrible and misinformed suicidal death. It’s also a prototypical comedy in that it can make fun of anything. Besides the mockery that the royal court contributes, absurdity is a central element of the humor. That the Queen of the Fairies can be enamored of a donkey is it’s own kind of hilarity, but the youths fall victim to all the absurd and irrational foibles of love. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a comedy of social mores (which are mocked in the pastoral setting), but it also jokes on the problems of love and courting that even exist in the natural (fairy) world – the little tempests, the changes of heart, the misunderstandings – all of which we can relate to, and with a little distance, have a good laugh over. Tone Light, Mocking, Airy The play is, essentially, not that deep. Not that its issues don’t run deep, but the issues are more superficial than anything earth shattering. Shakespeare introduces dark material, but even that is done with a light touch: Hermia can dodge a death sentence by a moonlit escape with her lover, Pyramus and Thisby’s suicides are comic, and Helena’s crushing romantic rejection can be solved with some love-juice. Puck, who often delivers the dark material of wolves and graves and all that stuff, is a fairy-ish sprite. As we all know, fairies are not that serious. It’s not just the content that’s light, but the magic of the play that makes it seem gauzy. Dreams and imagination, never mind magical fairies, are central to the story. Love has an ethereal, dream-like nature, which is only augmented by the magical spirits who have power over the goings-on of the night. Shakespeare acknowledges the night is a scary time, but he makes sure that nighttime is also fairy-time – a decidedly sparkling portrayal, more about the stars than the darkness that envelops them. Between lovers and fairies, and fairy lovers, the play can’t help but be light, a little mischievous, and all together delightful. Writing Style Flippant, Melodramatic, and Really Quite Lovely The content of the play allows Shakespeare some opportunity to mock his characters and the general glibness of the web of love in which they’ve been tangled. Even though the lovers’ escape is forced by the very serious possibility of Hermia’s death sentence, the escape to the wood allows the central problem of the play to be the lovers’ interactions with each other. They are plagued by misunderstandings and quick tempers. Shakespeare lightly mocks the stupid stuff love makes us do, but he also mocks human understanding and temperament; we often judge before we think. Characters change their minds and hearts faster than Alberto Gonzales changes stories. It’s hard to take them seriously when their main inspiration to love is pansy-juice. As a result, the lovers’ prose is often melodramatic, like Hermia’s curses of Helena, and Demetrius and Lysander’s mutual chase. Shakespeare uses the Mechanicals’ play to be a mock-up of that kind of feeling: Pyramus and Thisby are so melodramatic in their language that their feelings seem silly and trite, but actually, their feelings aren’t that different from Lysander, Demetrius, Hermia, and Helena’s. The saving grace of the play is the loveliness of the language in the fairy parts. The lilting and lush images of Titania laughing, or of a fairy gathering dewdrops to hang like ornaments on flowers bowing to the morning are unparalleled. Shakespeare can mock the frivolity that naturally comes with love, but at heart he’s a poet, and reveres the wonders of nature. What’s up with the title The title clues us in on when the story occurs. Locating the action within a particular time of the year establishes up how we should think of the play. The “Midsummer” part means that it’s the time of year for May Day and the summer solstice. These notions focus our attention on celebration, fertility, and the influence of the natural world on the human realm. The "Dream" part of the title is important, too. Dreams are central to explaining the fairy world within the play, but dreams provide a broader motif as well. At the closing of the story, Puck likens the world of the play to a dream. This comparison is a big idea you should carry with you: both plays and dreams, although they contain elements of reality, are removed from reality. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as a whole, can be seen as a commentary on the different versions of reality that make up our own human story, which is at times odd enough to be a dream.

![A Midsummer Night`s Dream Pwr Pt[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005762557_1-5af7c72ea5c24654d8d99c77f3efc253-300x300.png)