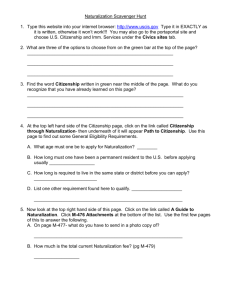

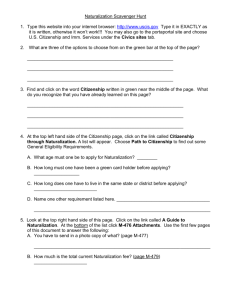

014.doc - Columbia Law School

advertisement