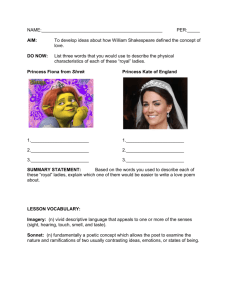

1 - PURE

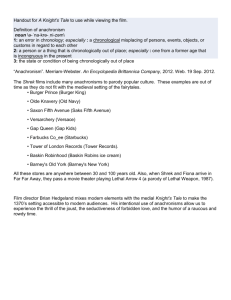

advertisement