Here - Ambleside Online

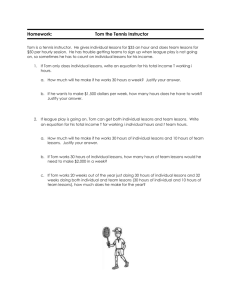

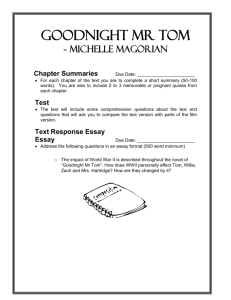

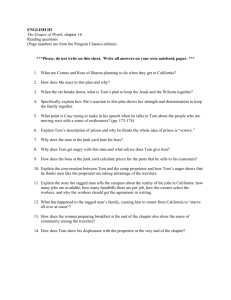

advertisement