Introduction - Blogs @ Baylor University

advertisement

Mystery, Manners and Violence:

Flannery O’Connor’s Ontology in Light of Hart’s The Beauty of the Infinite

by

Nathan Carson

for

ENG 5308: Ontology and Literary Theory

Dr. Phillip Donnelly

May 9th, 2007

Carson 1

I. Introduction

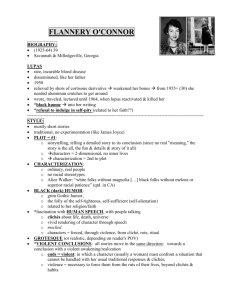

Flannery O’Connor is a writer known for her violent fiction. Indeed, many readers,

unable to stomach the intensity and grotesqueries of her work, leave off after finishing a single

short story. However, O’Connor was also a well-read, self-taught theologian, and she often

persisted that her Catholic theology was the singular driving force behind her artistic work. In

light of the difficulty of violence in her work, it may be provocative to suggest that her

theological allegiances, and thus perhaps her fiction, bring her into striking alignment with David

Bentley Hart’s theological understanding of a Christian “ontology of peace.” In his Beauty of the

Infinite, Hart, argues that Christianity marks the essential rupture between the age-old

ontological polarity between Apollo and Dionysus, both of which hold to violence as a

necessary, a built-in inevitability in the fabric of reality itself.

Does O’Connor, given her violent proclivities, hold to an ontology of violence or of

peace? In this paper we intend to demonstrate that O’Connor’s theology parallels Hart’s

“ontology of peace” in three central ways: she takes the surface of sensible reality with utmost

seriousness, explicitly sees the Incarnation as the rationale for this, and holds to the analogia

entis, whereby the sensible surface of reality, including rhetoric itself, participates in the mystery

of the divine life. With this claim in hand, we will also argue that in her non-fictional work,

O’Connor does not see violence as ontically necessary or “redemptive,” but rather as wholly

instrumental to her invective against nihilism and to the opening of her readers and characters to

the possibility of grace and the vision of divine mystery. Finally, however, we will also offer a

reading of O’Connor’s “Good Country People,” in which we will argue O’Connor achieves only

partial success in embodying an ontology of peace. In order to demonstrate these claims, we will

delve briefly into Hart’s trenchant analysis of the necessary violence inherent in Apollonian and

Carson 2

Dionysian metaphysics, together with his suggestion that a Christian ontology of peace is an

unprecedented interruption between them. Next we will examine O’Connor’s non-fiction in

order to show her fundamental alignment with Hart’s ontology of peace, followed by an

explication of her comments on violence, in order make sense of the place violence occupies in

her ontology. Finally, we will offer a reading of O’Connor’s “Good Country People,” in order to

see how O’Connor’s ontology of peace fares in the context of her fiction.

II. Hart’s Aesthetics of the Surface

The history of Western metaphysics has been fraught with presuppositional problems,

stemming from late scholastic nominalism, of a rupture between the surface of being and the

veiled sublime. In all its manifestations Western metaphysics has been an effort to impose

mastery over the “real” by reference to its “ground” which lies veiled behind it (Hart 415). In this

sense traditional Western metaphysics, from Parmenides, through Plato, to Malebranche,

embodies a cosmic Apollonian order which for Hart, is at bottom a nihilistic ontology of

violence. The protest leveled against this history was most clearly articulated by Nietzsche, who

recognized the incipient nihilism of this approach in its denial and evaporation of meaning from

the surface of existence, as the particular is surrendered to the universal.i In addition to Hart’s

critique of the necessary violence inhering in the Greek Attic tragedies, Rene Girard adds that the

ancients either considered violence part of the divine, or they saw the inflicting of violence upon

an innocent victim as a necessary means of preventing large-scale outbreaks of violence and

preserving societal order and peace (Girard 49ff.). Either way, violence was seen as an inevitable

part of being as such, and the focusing of violence on a particular individual for the sake of the

Carson 3

universal order, is one example of the need for an Apollonian ontology to slight the particular in

order to preserve a universal order.

Among those opposed to Apollo, Nietzsche leads the way. Thus Nietzsche is in one sense

(and only one!) the father of postmodernity in its nearly unilateral suspicion of totalizing

metanarratives and fervent project to tell the story of the death of metaphysics; the universal is

annihilated in favor of the particular. However, Hart suggests that as much as all things

postmodern emphasize the death of metaphysics, nearly all its forms hold on to one central

metaphysical assumption: “that the unrepresentable is; more to the point, that the unrepresentable

(call it difference, chaos, being, alterity, the infinite…) is somehow truer than the representable

(which necessarily dissembles it), more original, and qualitatively other” (Hart 52). Thus, for

Hart, even the postmodern act of renouncing mastery over the “grounds” of being and the

departure from any and all foundations that might be lurking behind sensible existence,

inevitably asserts itself as yet another tyrannical monopoly over the nature of reality, another

narrative that would render all others censured and inept (Hart 421). In denying and resisting all

narratives of “closure” and homogeneity, this “narrative of the death of metaphysics”

inescapably becomes another sort of “‘colonial’ discourse of its own, imperiously inscribing its

negations across every other narrative” by reserving for itself a privileged extra-metanarrative

space whence to act as final arbiter and judge (Hart 420):

…postmodernity, broadly speaking, neither subverts nor reverses metaphysics, but simply

confirms it: it preserves a classic polarity within the metaphysical tradition, though it

embraces one pole rather than (as is traditional) the other. It merely marks the triumph of

Heracleitos over Parmenides, of the narrative of being as dynamic flow and aimless

differentiation over the narrative of being as immobile totality. If indeed metaphysics, in its

every manifestation, is really the attempt to erect a hierarchy within totality that will still the

turbulence of difference, dam up the alluvial force of becoming, and scaffold Dionysian

energy in a framework of Apollonian reserve, the collapse of metaphysics must be (for

thought) the setting free of chaos and its prodigal play of creation and destruction. But a

mirror preserves the image it inverts. (Hart 37-38)

Carson 4

As Hart further notes, the victory of a narrative of being as flux and dynamism, of the interplay

of “creation and destruction,” inevitably remains tied not only to the polarity between Apollo and

Dionysus, but in favoring the latter, it effectively glorifies violence and reduces all transactions

in the world to raw assertions and counter-assertions of the insatiable Dionysian will-to-power.ii

For Hart, both Apollonian order behind the surface of sensible being, which must sacrifice the

particular, and the Dionysian affirmation of the sensible world in all its difference as it hovers

above the void of chaos, both exist as totalizing systems, as ontologies of violence.

Christian ontology is by contrast, says Hart, is an “ontology of peace” that disrupts and

rejects either side of this ancient duality; it affirms the goodness of the surface of being and

denies that violence is inevitable or necessary for the good. Such an ontology, Hart adds, affirms

the whole of sensible reality—including the goodness of the textual surface, of rhetoric and

metaphor—since it participates analogically in the peaceful and beautiful difference of the

infinite.iii For Hart, the surface of being as such is groundless, as all finitude is perpetually taken

up into the beauty of the infinite, the latter of which can be known, though not exhaustibly, by

way of analogy, rhetoric and metaphor precisely because of the Incarnation of Christ, the form

and infinite beauty of the divine logos. Only such an ontology—first made possible by the

Incarnation of God—whereby the surface of sensible reality participates by analogy in the

infinite beauty of God, can really plumb the full depths of the surface and fully expose and

oppose violence as utterly surd, without also depending on it as an ontic necessity. As Erich

Auerbach has shown, the history of Western representation of reality was utterly changed by the

Christian claim that God had become incarnate. Everything in the sensible world, including the

most mundane of daily tasks or the most insignificant of peasant lives, became freighted with the

Carson 5

utmost significance since all participated in the life of God himself; all of sensible reality was

now potentially a site for the holy (Auerbach 194, 198).iv

In Hart’s view, any attempt to posit a veiled ground of being and “get behind” or beneath

its “surface,” or to cut the surface off from analogical participation of finitude in the difference

and beauty of the infinite, inevitably leads back into the totalizing gridlock between the order of

Apollo and the chaos of Dionysus and their nihilistic ontologies of necessary violence. Thus he

says that “…against the God declared in Christ, Dionysus and Apollo stand as allies, guarding an

enclosed world of chaos and order against the anarchic prodigality of his love” (Hart 127). In

opposition to this unholy alliance, Hart argues that Christ himself marks a fundamental break

from the whole system of ontological violence and totalizing systems of mastery over reality. In

light of this, Hart contends that the Christian posture must be an embrace of the surface of being:

“Theology should always remain at the surface (aesthetic, rhetorical, metaphoric), where all

things, finally, come to pass” (Hart 28). Rather than being concerned with grasping the “depths”

of reality and so turn Christian truth into a series of abstractions in collusion with ontological

violence, Hart contends that the Christian grasp must be of the surface of reality, that “fabric” in

which God’s glory is given splendid, assorted, and dynamic expression (Hart 24). For Hart,

theology should take its cue from the prodigality, gratuity and superficiality of divine beauty that

finds its singular habiliment in “the intensity of surfaces, the particularity of form, the splendor

of created things” (Hart 24).

Carson 6

III. O’Connor’s “Mystery and Manners”

Manners

At least in her non-fiction, O’Connor aligns, we will argue, quite closely with Hart’s

general argument: she is intimately focused in her work on the surface of sensible reality, views

the Incarnation as the foundation under girding this approach, and embraces the analogia entis,

whereby the surface of being, including the symbols inhering in fictional texts themselves,

participates in the mystery of the divine life. Our aim for this portion of the present study will be

to demonstrate this congruence with Hart’s “ontology of peace,” in order to fully contextualize

the issues involved in understanding how, and in precisely what way violence can figure so

centrally in O’Connor’s fiction.

Throughout her brief life O’Connor spent a great deal of effort exploring, in her aesthetic

theory and fiction, the relation between “surface” and “depth.” Indeed, the twofold relation of

“mystery” and “manners,” comprising the title of the collection of O’Connor’s comments on her

own work, bespeaks her central concern with the sensible, concrete specificity of manners on the

one hand, and the boundless depths of mystery on the other. For O’Connor, mystery and manners

are the two central qualities that make fiction work (MM 103). When she speaks of “manners,”

O’Connor is referring to “the texture of existence” that surrounds human beings, especially in its

regional or local character. For the southern writer, an emphasis on manners will mean a specific

focus on the social fabric, local idiom, and unique aspects of the Southern region, and this

emphasis provides O’Connor with the subject matter, setting and characters of her fiction, which

remain deeply rooted in southern landscapes, Protestant fundamentalism and (comic) depictions

of southern manners and hospitality.

Carson 7

More broadly, however, “manners” serves as a term for sensible, concrete reality in

general. Thus O’Connor continually emphasizes that good fiction must appeal “through the

senses” because that is where human knowledge and perception begins; “you cannot appeal to

the sense with abstractions” (MM 78). She contends that good fiction is not “an escape from

reality,” but rather “a plunge into reality” that is “very shocking to the system” (MM 78), and it is

this emphasis on the concrete and the sensible that explains O’Connor’s description of herself as

a “realist.”v This “realism” which seeks to “penetrate the concrete” derives, for O’Connor,

precisely from Augustine’s theological affirmation that the sensible “things” of the created world

are good because they “pour forth from God” and “proceed from a divine source” (MM 157).

However more important than the divine source of sensible reality, for O’Connor, was

the thorough coinherence of the finite with the infinite, of the human and the divine, in the

person of the incarnate Christ (MM 68). Indeed, O’Connor’s rootedness in the sensible things of

the world derives ultimately from her belief in the Incarnation. O’Connor’s opposition to the

anti-incarnational “Manichean imagination” that would separate matter and spirit is wellattested. What is notable, however, is that in her invective against Manichean sensibilities,

O’Connor was highly influenced by Jesuit theologian William F. Lynch.vi In his book Christ and

Apollo, for which O’Connor published an enthusiastic review, Lynch equates the Manichean

“disease of the imagination” with Apollo, whom he saw as the “infinite dream” opposed to the

“definiteness and actuality” of Christ incarnate (Lynch, CA, xiv; TA, 66). In addition to calling

Lynch “one of the most learned priests in this country” and repeatedly recommending his works

to her friends, in her copy of Lynch’s article, “Theology and the Imagination,” O’Connor

underlined Lynch’s assertion that “Christianity has from the beginning demanded that the search

for redemption and the infinite be through the finite, through the limited, through the human”

Carson 8

(Lynch, TA, 66). Elsewhere, O’Connor’s emphasis on the need for novelists to fully “penetrate

the concrete” is taken nearly verbatim from Lynch, who stressed the Incarnate Christ as the

touchstone for the whole of Christian imaginative work (Lynch, xiv).

All of this serves to underscore the fact that, for O’Connor, the “surface” of sensible

reality was crucially important because of the Incarnation of Christ, in whom the surface would

forever be inscribed with fresh registers of meaning that inhere within it and reach beyond it.

Such is Auerbach’s point in his chapter on Dante in Mimesis: the Western representation of

sensible reality in all its social, political, mundane and particular vicissitudes was made possible,

chiefly, by new avenues opened to the Western imagination by the Incarnation, whereby finite

realities could be utterly finite, and yet participate in something beyond the finite at the same

time.vii

The point in all of this discussion is merely to highlight the way in which O’Connor’s

view of reality was utterly opposed to Apollonian ontology, which she viewed in a way that was

similar to Hart, as a flight from and thus necessarily enacting violence against the particulars of

sensible reality for the sake of getting “behind” it to its universal grounds.viii The Apollonian

ontology of necessary violence, whether the particular violence against a sacral victim for the

sake of preserving the polis, or the more general violence of slighting the sensible for the sake of

an ordered backdrop is, as far as we can gather from her non-fiction, foreign to O’Connor’s view

of reality. This is most evident, however, in her explication of the way sensible reality, including

her own fictional texts, mysteriously participates in the life of God.

Mystery and Analogia Entis

Carson 9

As if to predict the Dionysian ontology of violence presupposed by critical constraining

of texts as the mere free play of signifiers, O’Connor recognized that all too many people in the

modern world embrace the wholly naturalistic idea that the “reaches of [our] reality end very

close to the surface” (MM 157). Thus O’Connor adds her emphasis on “mystery” as an essential

element of being that is disclosed when the artist “penetrate[s]” the natural world (MM, 163).

The true novelist knows, she contends, that he must “make his gaze extend beyond the surface,

beyond mere problems, until it touches that realm which is the concern of prophets and poets”

(MM 45). For O’Connor, this “realm” is the special province of “mystery,” which involves “the

Divine life and our participation in it” (MM 72). The mystery of life, for O’Connor, is that at the

depths of the concrete world lies “the image of its source, the image of ultimate reality,” which is

that divine life from which all sensible things proceed (MM 157).

Of course the phrase “beyond the surface” immediately has potential for implicating

O’Connor in the violent ontology of Apollo. However here we must keep firmly in mind the

incarnational understanding at work here. Christ himself, as fully human and divine in one

person, is the foundation of the “Christic imagination” as Lynch calls it, such that the finite and

infinite, the sensible and invisible, manners and mystery share, in Lynch’s words, a relation of

“unqualified interpenetration” such that, much like Hart argues, difference is all the more truly

upheld.ix This explains O’Connor’s explicit critique of both Graham Greene and Francois

Mauriac when they make a kind of unexpected, deus ex machina appeal to the supernatural in

their novels; for O’Connor this is the Manichean imagination at work, the Apollonian violence

against the surface in an appeal to what lies “behind” it.x Thus, when O’Connor speaks of going

“through” or “beyond” the surface, she simply means that there is far more to reality than mere

Carson 10

surfaces, but that in the pursuit of vision into the mystery of reality, the literal level of the surface

can never be slighted or left behind (MM, 41-42).

This theological seed of O’Connor’s view on the interpenetration of mystery and manners

grows to bear much interpretive fruit when we realize that she connects the theory to her

understanding of the literary symbol, which she explicitly ties to the analogy of being presumed

in the medieval exegesis of Scriptural texts.xi For the medieval exegetes, the literal, or historical

meaning of the biblical text could never be left behind; it was always maintained within their

interpretations of the text’s additional registers of meaning: the allegorical, typological and

anagogical. O’Connor explicitly ties this practice to the kind of vision a writer ought to have:

The kind of vision the fiction writer needs to have, or to develop, in order to increase the meaning

of his story is called anagogical vision, and that is the kind of vision that is able to see different

levels of reality in one image or one situation. The medieval commentators on Scripture found

three kinds of meaning in the literal level of the sacred text: one they called allegorical, in which

one fact pointed to another; one they called tropological, or moral, which had to do with what

should be done; and one they called anagogical, which had to do with the Divine Life and our

participation in it. Although this was a method applied to biblical exegesis, it was also an attitude

toward all of creation, and a way of reading nature which included most possibilities, and I think it

is this enlarged view of the human scene that the fiction writer has to cultivate if he is ever going to

write stories that have any chance of becoming a permanent part of our literature.” (MM, 72-73)xii

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that O’Connor claims that her own fiction functions much

(though not entirely) the same way as the biblical text, wherein the literal symbols in her stories

always remain literal and necessary to the story, while also taking on additional registers of

meaning that somehow make “contact with mystery.” Again, the incarnate Christ provides the

foundation not only for viewing existence as such and human reality itself as participatory of the

life of God through the analogia entis, but also for viewing language this way, analogia verbis,

wherein human rhetoric and literary symbol also participate, by analogy, in the life of God.

Consequently, throughout her stories, O’Connor perpetually looks for an image or literary

symbol that is at once literal and opens out into an “anagogical vision”; a symbol that contains a

Carson 11

polyphonic register of meaning wherein the literal brims with the life of God and our

teleological participation in it:

I often ask myself what makes a story work, and what makes it hold up as a story, and I have

decided that it is probably some action, some gesture of a character that is unlike any other in the

story, one which indicates where the real heart of the story lies. This would have to be an action or

a gesture which was both totally right and totally unexpected; it would have to be one that was both

in character and beyond character; it would have to suggest both the world and eternity. The action

or gesture I’m talking about would have to be on the anagogical level, that is, the level which has to

do with the Divine life and our participation in it. It would be a gesture that transcended any neat

allegory that might have been intended or any pat moral categories a reader could make. It would

be a gesture which somehow made contact with mystery. (MM 111)xiii

By now it should be fairly evident that—not least in light of her immersion in the NeoThomism of Etienne Gilson and Jacques Maritain, as well as in the Angelic Doctor himself—

O’Connor explicitly shares Hart’s affirmation of the analogia entis and its complementary

analogia verbis (MM 71-72). Rhetoric and metaphor can indeed, in O’Connor’s view, reveal the

participation of the sensible world in mystery of the divine life. At least in the central “action” or

“gesture” that lies at the heart of her stories, and arguably outside of that moment as well,

O’Connor expects her literary symbols to open her readers to mystery. This, we perhaps need not

mention, thoroughly parts ways with both ontologies of violence inherent in Apollo and

Dionysus. The reasons for parting with the former have already been examined. However in this

section of our study it should also be evident that a Dionysian ontology of violence, suggesting

of a primal chaos of competing forces, as well as its postmodern incarnation, which locks down

the surface of sensible reality as the only thing we apparently have access to—a surface rife with

chaos and violence in which people, as well as texts, subsist merely as encoded discourses of

power—was also utterly foreign to O’Connor.xiv By now we hope to have demonstrated that

O’Connor shares with Hart three central aspects of a Christian ontology of peace in which

violence may happen, but is never necessary: in addition to her determination to root herself in

the surface of sensible being, O’Connor also grounds this approach in the Incarnation, and

Carson 12

finally holds to the analogia entis, whereby the sensible surface of reality, including rhetoric

itself, participates in the mystery of the Divine life.

What then are we to make of the violence that so pervades the fiction of this apparent

proponent of a peaceful ontology? How does this fit into the picture thus far drawn, and does the

fictional text ever “get away” and out from under O’Connor’s guiding view of reality? Whatever

we make of violence in O’Connor’s fiction, if these elements do indeed generally outline aspects

of O’Connor’s ontology, her very lenses for viewing reality, then when the fiction appears to

depart from this we should be no less vigilantly aware of our own ontological assumptions than

we are of O’Connor’s, before we assign to her texts a view of reality wholly foreign and utterly

contradictory to that of its author.

IV. Violence, Mystery and Grace

Violence as Instrumental Literary Technique

Unlike Hart and his emphasis on the beauty of the infinite revealed in the surface, a

perspective she was very well-acquainted with through Maritain’s suggestion that the artist’s task

was to illumine the splendor formae of divine beauty, O’Connor deems it necessary to distort the

surface in order to get at the depths of the mystery, both of the analogia entis and the “action of

grace” (Maritain 23, 28). For O’Connor, this need for distortion is partly due to the audience she

is writing to, and this explains some of her proclivities for the grotesque, including violence.

Bringing readers to the point of being able to recognize the mystery that inheres in sensible

reality will require, in O’Connor’s view, violent measures. The attempt to connect the surface of

things with mystery, through the use of multivalent symbols, is so intractably odd to the ordinary

reader, that O’Connor suggests “the look of this fiction is going to be wild…it is almost of

Carson 13

necessity going to be violent and comic, because of the discrepancies it seeks to combine;” the

writer of this fiction will have to “use the concrete in a more drastic way” namely, “the way of

distortion” (MM 41-42, 43). Thus O’Connor seeks to stretch the angles of concrete reality, render

them odd and ill-proportioned, grotesque, and infuse them with the bizarre.

By now we can discern that O’Connor’s fictional distortion of sensible reality, including

her use of grotesque images or characters, psychological extremity, and the suffering of physical

violence, all serve the instrumental telos of recalibrating her readers’ sensibilities to the point at

which they can perhaps be led into a vision of mystery. This is no easy task, in O’Connor’s

view, since the Christian artist has to recognize the aberrant perception of the sensible in her

modern audience, which is bolstered by acclimation to malignant societal structures and

sensibilities:

The novelist with Christian concerns will find in modern life distortions which are repugnant

to him, and his problem will be to make these appear as distortions to an audience which is

used to seeing them as natural; and he may well be forced to take ever more violent means to

get his vision across to this hostile audience. . . . [Y]ou have to make your vision apparent by

shock - to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and

startling figures. (MM 33-34)

The instrumental character of O’Connor’s approach is clear; the “large and startling figures,” the

grotesqueries and violence in O’Connor’s fiction, are there, at least in part, for the “hard of

hearing” and “the almost-blind.” In other words, her use of distortion is meant to be a revelatory

conflux of both manners and mystery to a modern audience largely immersed in materialistic

nihilism, and for whom the notion of Incarnation is madness.xv In her use of violence, the

grotesque and the bizarre, O’Connor attempts to pump oxygen into the lungs of those who

typically do nothing but “breathe in nihilism. In or out of the Church, it’s the gas you breathe.”xvi

From Instrumental to Necessary Violence?

Carson 14

The way O’Connor uses violence as an instrumental means of communicating her vision

must certainly be kept in mind when interpreting her fiction. However, beyond audience-oriented

tactics, one of the things that complicates her use of violence is that O’Connor typically

intensifies it precisely in the “significant action” or “gesture,” in that moment that is the “heart of

the story” when she tries to make “contact with mystery.” In essence this binds her central

“action of grace” to the most violent and disturbing part of each story, and this raises the

question: does divine grace and its revelation of mystery necessarily come about through

violence? This raises further questions: Is it the offer of grace or actual redemptive grace itself

that comes to O’Connor’s character’s through violence? Finally, does grace or the offer of grace

come those who inflict violence upon another, or to those who suffer violence as its

recipients?xvii Finally, are we to limit “violence” only to physical aggression, or can we also

account for non-visible forms of violence like the verbal and psychological, which are in fact its

most prevalent forms in O’Connor’s fiction? These are substantial distinctions, and result in

vastly different interpretations depending on which relation we discern at work in O’Connor’s

fiction.

However before we delve into an analysis of O’Connor’s story, “Good Country People,”

we must note here that, at least in her non-fiction, O’Connor is quite clear about the precise

nature of these relationships; she doesn’t simply slap on a label called “redemptive violence” like

so many of her critics. In a single passage that gathers together and integrates the main thrust of

her thinking here, O’Connor talks about the violence of the “significant action,” that moment of

grace and the response to it, and the nature of satanic involvement in making this moment

possible:

There is a moment in every great story in which the presence of grace can be felt as it waits

to be accepted or rejected, even though the reader may not recognize this moment.

Story-writers are always talking about what makes a story ‘work.’ From my own experience

Carson 15

in trying to make stories ‘work,’ I have discovered that what is needed is an action that is totally

unexpected, yet totally believable, and I have found that, for me, this is always an action which

indicates that grace has been offered. And frequently it is an action in which the devil has been the

unwilling instrument of grace. This is not a piece of knowledge that I consciously put into my

stories; it is a discovery that I get out of them.

I have found, in short, from reading my own writing, that my subject in fiction is the action

of grace in territory held largely by the devil. (MM 118)

Some interpretive observations are in order here. First, it is clear that the “action of

grace” does not indicate a kind of internal regeneration of the recipient, but rather an invasion

into the character’s reality that constitutes an offer. This seems to be the dominant mode of

O’Connor’s thinking, however there are times when the character is subject to the action of grace

with or without their own say in the matter. Such seems to be the case for Tarwater in The

Violent Bear it Away, both in the baptismal scene and the rape scene.xviii However even here,

these invasions of grace penultimately await the character’s definitive and final acceptation of

the offer of grace. In this passage we also see, secondly, that for O’Connor the devil is an

unwitting and “unwilling instrument of grace.” Again, however, it would seem that what she

implies is that the devil’s work can bring a person to the point at which grace is offered, but may

still be either accepted or rejected. We will see precisely this moment at work when we examine

“Good Country People.” What O’Connor by no means implies here, is that the devil (or satanic

character) is an instrument or agent of grace and the redemptive conveyor of grace. On the

contrary, says O’Connor, “In my stories a reader will find that the devil accomplishes a good

deal of groundwork that seems to be necessary before grace is effective” (MM 117). What is

more, there seems to be no indication, here or in her stories, that the violent act is in itself

redemptive, or that the perpetrator is somehow redeemed or purified in the act. Finally, for

O’Connor to say that the grace she depicts is at work specifically “in territory largely held by the

devil,” is also to say that the action of grace will, in such a context, necessarily be a kind of

violence relative to the level of recalcitrance in the recipient and complicity in the devil’s order

Carson 16

of things. Ultimately however, the devil doesn’t have to be tied to violence. This is evident in

perhaps the strangest portion of O’Connor’s view that, with respect to ends, violence is a kind of

neutral force or energy, an “extreme situation” which can instrumentally serve either good ends

or bad ones. Her comments on the matter clarify the concept here:

We hear many complaints about the prevalence of violence in modern fiction, and it is always

assumed that this violence is a bad thing and meant to be an end in itself. With the serious writer,

violence is never an end in itself. It is the extreme situation that best reveals what we are

essentially, and I believe these are times when writers are more interested in what we are

essentially than in the tenor of our daily lives. Violence is a force which can be used for good or

evil, and among other things taken by it is the kingdom of heaven. (MM 113)

With this final piece in hand, we suggest that at the far end of each salient element

examined in O’Connor, violence perpetually retains an instrumental quality. Whether used to

awaken a nihilistic readership, open a character to the operation of grace, or take the kingdom of

heaven by forceful advance, violence does not appear to be, for O’Connor, ontologically

necessary. Although O’Connor’s fictional world certainly doesn’t appear to come off as an

“ontology of peace,” we can at least say, nonetheless, that she does not hold an Apollonian view

of violence, wherein violence is always necessary, but held at bay by a universal order at the

violent expense of the particular, be that the sensible world as such (in the case of metaphysics),

or the redemptive act of violence inflicted on the sacral victim for the sake of the polis.xix It is

equally evident, however, that O’Connor avoids a wholly Dionysian ontology of violence,

whereby the forces of chaos and struggle are built into the fabric of being itself, and sensible

violence is either celebrated as a kind of liberating pathos or despaired over as the inevitable

destructiveness of relationships, political forces or textual signifiers. No matter how disturbing

and violent O’Connor’s texts may be, her instrumental view of violence automatically precludes,

in the full sense of these views, an Apollonian or Dionysian ontology of violence.

Carson 17

V. Ontology and Violence in “Good Country People”

In O’Connor’s story, “Good Country People,” we are introduced to the main character,

Joy Hopewell, who has had her name changed to “Hulga.” Clearly reminiscent of O’Connor’s

own terminal illness and confinement in her mother’s house in Milledgeville, Georgia, Hulga is

an intense intellectual, stuck at the age of 32 in her platitude-spouting mother’s house in a small

backwater southern locale full of “good country people.” Hulga has her PhD in philosophy, but

her weak heart keeps her from being able to leave her mother’s house or the southern backwoods

life. In addition, at the age of ten a hunting accident occurred in which one of Hulga’s legs was

blasted off by a shotgun; she now wears a prosthetic leg (CS 274). All of these bleak details

combine to form a character who is thoroughly disgusted with her life, and determined to

embody her disgust in her every action, interpersonal gesture and intellectual belief.

With this in mind, the first point of analysis on violence in this story is that of Hulga’s

violence against herself. She is so disgusted with the clichés which her mother spouts off, like

“nothing is perfect,” and “a smile never hurt anyone,” that she utterly refuses to entertain any

sympathy toward her mother’s mannerisms whatsoever. The narrative voice in fact subtly aligns

with Hulga’s critique:

Mrs. Hopewell had no bad qualities of her own but she was able to use other people’s in such a

constructive way that she never felt the lack…Mrs. Hopewell was a woman of great patience. She

realized that nothing is perfect and that in the Freemans she had good country people and that if, in

this day and age, you get good country people, you had better hang on to them. She had had plenty

of experience with trash. (CS, 272, 273)

The difference, however, between this subtly sarcastic and ironical tone of the narrator, and

Hulga’s response to it, is substantial. At one point in the story Mrs. Hopewell recalls how Hulga

exploded at the dinner table “without warning and without excuse…her face purple and her

mouth half full,” screaming, “Woman! do you ever look inside? Do you ever look inside and see

what you are not? God!” (CS 276) The narrative voice, employing Mrs. Hopewell’s own

Carson 18

thoughts on the matter, wryly concludes the scene: “Mrs. Hopewell had no idea to this day what

brought that on. She had only made the remark, hoping Joy would take it in, that a smile never

hurt anyone” (CS 276).

While subtly critiquing Mrs. Hopewell’s platitude-laden, sugar-coated view on life,

O’Connor’s narrator also suggests that Hulga’s rage is violently stripping her of personhood and

reducing her to a machine; the “large hulking” Hulga’s “constant outrage had obliterated every

expression from her face” while her “icy blue” eyes betray the “look of someone who had

achieved blindness by an act of the will and means to keep it” (CS 273). Hulga’s machine-like

personhood is emphasized through the mannerisms she takes on, such as her intentional

stumping around the house “with about twice the noise necessary,” her attempts to add a look of

“blatant ugliness to her face,” and finally in her “highest creative act” of legally changing her

name from Joy to Hulga: “She had arrived at it first purely on the basis of its ugly sound and then

the full genius of its fitness struck her. She had a vision of the name working like the ugly

sweating Vulcan who stayed in the furnace and to whom, presumably, the goddess had to come

when called” (CS 275). In equating herself to the Roman god of fire and metal-working, Hulga

achieves the ultimate violence against herself.

As the narrative proceeds, however, it becomes clear that the violence of Hulga’s stance

toward herself and her mother is an embodiment of O’Connor’s unflagging critique of nihilism,

of which Hulga is an explicit proponent. The grotesque and angular images with which she

describes Hulga, serve the instrumental purpose of revealing the true character of the nihilist

“gas we breath” to her implied readers; surely the smoke typically linked with the forge and fire

of Vulcan implies this.

Carson 19

Another technique by which O’Connor emphasizes the hostility of nihilism in its violent

and privative effect on humanity, is the ironical relation she draws in this story between

blindness and sight. Although Hulga says that “some of us have taken off our blindfolds and see

that there is nothing to see,” she is in fact unable to see at all, “having achieved blindness by an

act of the will” (275) but also receiving blindness against her will when her glasses, as well as

her prosthetic leg stolen from her later on (287). If the stolen glasses weren’t enough, the narrator

suggests that even if she did have them on, she would still be unable to see anything

“exceptional” in the landscapes around her, “for she seldom paid any close attention to her

surroundings” (CS 287). This is highly significant, because for O’Connor, the ability to see (even

through physical blindness) the mystery and analogical inexhaustibility of the divine life

illumining the natural world, is utterly essential for anyone who would embrace full humanness

the peace of being.

The reason the instrumental character of O’Connor’s depiction of Hulga must be noted, is

because there are numerous interpreters who take these grotesqueries and violations of

personhood and construct an ontology of violence out of them, assigning it to O’Connor.xx

Others take the different approach of ignoring O’Connor’s actual view of reality, and instead

forcibly impose their own ontology of violence onto the story. One example of this move is

clearly evident in Christine Atkins’s feminist interpretation of this story as a “rape script.”

Misreading the depth of O’Connor’s critique of nihilism by assuming O’Connor’s point-of-view

aligns with the “God-fearing and eternally optimistic” Mrs. Hopewell and “her cache of clichés,”

Atkins decries the way the story “fractures” Hulga’s “subjectivity,” whereby her “rational mind,”

“masculine persona” and the “cumulative power of years of education—a central aspect of her

identity,” is “shattered” (Atkins 126-127). Atkins clearly prizes the resources of personal

Carson 20

autonomy and will-to-power that Hulga embodies: her intellectual might, her masculinity, and

her sense of being in control are all praised by Atkins. It is interesting that in bemoaning the

“rape-script” in which Hulga is violated by the bible salesman, Atkins expresses no qualms

whatsoever about Hulga’s sinister objective to violate him; since this intention springs directly

from Hulga’s prized intellectual power and strength of subjectivity, it is somehow above

reproach. In lamenting the loss of Hulga’s intellectual powers, Atkins seems to forget that

Hulga’s sardonic use of those powers, toward the end of believing in nothing, is precisely what

legitimates Manley Pointer’s violation of Hulga at the close of the story; the only difference is

gender. Unlike Hulga’s inability to retain absolute nihilism, he’s “been believing in nothing ever

since I was born” (CS 291), and this enables him, without any reservations at all, to utterly

violate and humiliate Hulga since all things are permissible for him.

If, as Atkins suggests, what constitutes violence is anything that reduces another person’s

strength of autonomous subjectivity, then we certainly wouldn’t want to “violate” Adolf Hitler,

for instance, for his intellectual powers, control, strength of belief and disdain for others; though

perhaps we would, since he is male. The point is that what quickly emerges from Atkins’s

analysis is a Dionysian ontology wherein one will to power is subverted by another, and the

violence is inevitable. This is clearly evident in a closing statement she makes: “His [Pointer’s]

violation and humiliation of her are redemptive and necessary because her rejection of religion

and affirmation of masculine characteristics function to undermine the patriarchal order of

things” (Atkins 127).xxi While Atkins admirably intends to oppose a text that may legitimate

sexual violation, it comes at too high a price, since she fails to realize that her own Zarathustran

ontology under writes the very violation she opposes. Patriarchal domination may win in this

case, but the solution Atkins proposes would be simply to replace it with female domination. In

Carson 21

any case, it is clear why she fails to catch O’Connor’s critique of Hulga’s nihilism; Atkins

herself is an unreflective proponent of nihilism, the Dionysian ontology of necessary violence

Atkins’s focus on the central moment of violation in this story brings us to the final scene

that we have space here to consider. Earlier we spoke of the way in which O’Connor seeks, in

the height of the moment of “contact with mystery” and possibility of grace, to use multivalent

literary symbols that can open the text itself up to mystery. One example of such a singular

image that is at once concrete and releases additional levels of vision is Hulga’s wooden leg.

O’Connor comments:

As the story goes on, the wooden leg continues to accumulate meaning ... by the time the

Bible salesman comes along, the leg has accumulated so much meaning that it is, as the

saying goes, loaded. And when the Bible salesman steals it, the reader realizes that he has

taken away part of the girl’s personality and has revealed her deeper affliction to her for the

first time. If you want to say the wooden leg is a symbol, you can say that. But it is a wooden

leg first, and as a wooden leg it is absolutely necessary to the story. It has its place on the

literal level of the story, but it operates in depth as well as on the surface. It increases the

story in every direction, and this is essentially the way a story escapes being short. (MM 99100)

In this example we discern that although O’Connor seeks to “penetrate” the surface of her

fictional text, like the medieval exegetes she does not leave the literal surface behind but rather

opens it up to mystery. This example also shows the way in which physical objects like wooden

legs are linked up to dramatic actions of violence through which, like the Sophoclean tragedy,

O’Connor unveils the central action which is “both totally right and totally unexpected.”xxii In

fact, O’Connor admits that she didn’t realize the leg needed to be stolen until about ten lines

before it happens.xxiii Thus when the bible salesman makes off with Hulga’s wooden leg, which

“she took care of…as someone else would his soul,” she is divested of multiple aspects of that

autonomous edifice of personhood which she has constructed for herself: her intellectual

superiority is stripped by someone thought to be cognitively inferior; her familiar mode of

exerting her will to power is thwarted by the reversal of her intent to seduce him; her amoral

Carson 22

nihilism is turned against her and its ends are revealed as utterly evil; her attempt to rid herself of

female gender is subverted. Thus, for O’Connor, the most disturbing and poignant instance of

violence, the gesture or action that is “unlike any other in the story,” is intended as the highdensity moment of grace offered to her characters.xxiv This illustrates her view that while

violence is never “an end in itself,” even so “grace must wound…before it can heal” and that

“violence is strangely capable of returning my characters to reality and preparing them to accept

their moment of grace” (MM 112).xxv

However, what are the implicit effects of this scene, which leaves Hulga “sitting on the

straw in the dusty sunlight” with a “churning face?” Does the wooden leg do its work, such that

when it is stolen, the reader, as well as Hulga herself, are brought into contact with mystery and

offered a kind of grace? We suggest that in this case, any positive sense of O’Connor’s ontology

appears to be compromised. There is no vision of “depth upon depth” as with Hazel Motes in

Wise Blood, no burst of sunlight and influx of “arabesque” colors as with Obadiah Elihue in

“Parker’s Back,” and no sight “suddenly restored” by a “light unbearable” as with Mrs.

Greenleaf as she is gored by a bull. Everything that happens to Hulga, by contrast, is a thorough

stripping away. The only clue we are given that this violence is indeed instrumental and in

service of a constructive good, is the sunlight shining on Hulga’s face, though even that is

“dusty,” and in any case the sunlight imagery is ambiguous in this story. While the light of the

sun could evoke, as O’Connor’s other narratives often suggest, an entrance into the divine

mystery and thus possible grace for Hulga, the sun can equally be a “cosmic metaphor for the

divine eye,” a “malevolent witness” or judge (Bleikasten 80). Which of these two it is, is usually

clearly suggested in the text; here the sunlight is simply “dusty.” Aside from the sun, the only

“contact with mystery” we are given is the image of Hulga’s “churning face,” which looks out,

Carson 23

without clear vision in the absence of her glasses, on the same vague “green speckled lake” she

looked at earlier, though before she saw “two green swelling lakes” (CS, 287, 291). Her vision is

not clarified, and the “mystery” which is offered to reader is a very vague one indeed.

Where O’Connor further seems to undermine consistency of her images is in the presence

of “wooden imagery.”xxvi McMullen notes that wooden imagery is sometimes used by O’Connor

to suggest the cross and redemption, while at other times it signifies the “wooden soul” of her

recalcitrant characters. Given Hulga’s wooden leg, are we to read its robbery as a moment of

gracious opportunity, or of an ugly, stubborn and reprobate nihilist being shut out of the kingdom

forever? In this image as well as others, O’Connor’s ambiguous use of the concrete “continually

sets up turmoil in the minds of O’Connor’s readers trying to achieve consistency of image and

meaning” (McMullen, 74).

Another element contributing to narrative obscurity is what McMullen calls the

“grammar of negativity.” Here she offers a statistical analysis of the percentage differential, from

the time Hulga meets the bible salesman to the end of the story, between positive and negative

verbal constructions. If this story is supposed to lead up to Hulga’s violation as a moment of

potential redemption, then why are the vast majority of verbal constructions negative in this

story?xxvii While O’Connor explicitly attributes her “fierce” and “negative” narrative voice to her

battle against nihilism, clearly applicable here as the “gas” Hulga and Pointer are breathing, the

implicit effect of this negative grammar seriously mitigates any sense of redemptive possibility

for Hulga after the robbery of her leg.xxviii As we have noted, the supposed moment of

redemptive possibility is immediately followed by a description of Hulga who “was left” with

her “face churning.”xxix The reader is left, then, with a sense of ambiguity over whether the

Carson 24

horrific violation of Hulga is indeed instrumental of a grace that opens her to redemptive

possibilities.

It doesn’t help that negative constructions continue to plague the narrative even after the

supposed moment of grace occurs. Indeed, O’Connor often follows epiphanic moments with

such a negative conclusion in her other stories, producing just the same effect.xxx Here the

negative ending is also granted ironic reversal as the salesman, who is the villain, is depicted

instead as running across a field, “struggling successfully over the green speckled lake,”

reminiscent of Jesus walking on water (CS, 291). The implicit effects of the story leave the

reader wallowing in the murk of uncertainty. In terms of ontological assumptions then, the effect

produces not a comedy of redemption accompanied by instrumental violence, but rather

something more akin to Greek tragedy; Hulga has been duped by the gods and by fate. What we

do have in hand, however, is an entirely negative argument aimed at stripping down the defenses

of nihilism, and showing its true violence for what it is. In that sense, then, it could be that

O’Connor intends the violation of Hulga to merely bring this point fully home. What threatens to

overwhelm that point, however, is the sense of tragic helplessness in the face of fate which, of

course, is an aspect of an ontology of necessary violence.xxxi

However, while this ambiguity is certainly a problem, there are nonetheless some

interpretations which O’Connor’s ontological assumptions, even if only negatively, preclude.

These interpretations would, in this context, view Manley Pointer’s violation of Hulga as either a

celebration of the “liberating power of destruction,” or as a violence that is redemptive for him,

such that violence itself is “an expression of the sacred.” We will examine these two possibilities

in turn. The first comes from a critic who imports her Dionysian ontology of necessary violence

into O’Connor’s fiction:

Carson 25

In images or isolation and entrapment, O’Connor defines a world where life is a perpetual struggle,

erupting in acts of violence, subsiding in an emotional void…. If she set out to make morals, to

praise the old values, she I ended by engulfing all of them in an icy violence. If she began by

mocking or damning her murderous heroes, she ended by exalting them. She grew to celebrate the

liberating power of destruction. O’Connor became more and more the pure poet of the Misfit, the

oppressed, the psychic cripple, the freak—of all of those who are martyred by silent fury and

redeemed through violence. (Hendin 87)

Given the ground we have covered thus far it should be clear that such a Dionysian celebration

of “the liberating power of destruction” is utterly foreign to O’Connor’s view of reality. In

addition, the multiple sets of binaries running through Hendin’s treatment, and her argument that

O’Connor grew to celebrate the conflict between the two, clearly implicates her in a postmodern

ontology of violence which presupposes the rhetorical violence of the text.xxxii Hendin’s

proclivity for difference will perhaps only issue, as Hart has soundly argued, in the totality of a

univocal meta-metanarrative that would exclude all others. To be fair to Hendin, Hulga’s story

could possibly be seen as the “liberating power” of the destruction of nihilism, though that is

clearly not the point Hendin is after here.

This leads into the second precluded interpretation, beginning with the observation that

Hendin uses the ambiguous phrase, “redeemed by violence,” with reference not only to the

victim, but to O’Connor’s most notorious murderer as well, the Misfit. By implication we can

say that for Hendin, Manley Pointer is somehow “redeemed” by virtue of his violation of Hulga,

his theft of her leg. This of course would be to sacralize the violent act itself, a view peddled

elsewhere by Parrish. In his analysis of O’Connor, Parrish, apparently forgetting Girard’s

unambiguous advocacy of a non-violent gospel, claims that O’Connor and Girard agree that

“there can be no return of the sacred without violence” (Parrish 43). Parrish misses the fact that

this view constitutes Girard’s depiction of an Apollonian ontology, wherein the inflicting of

violence upon a sacral victim was necessary for the preservation of societal order (Girard 49ff.).

Girard examines this view in order to contrast it with the Christian view, that the inflicting of

Carson 26

violence upon a victim is wholly unnecessary for the return of the sacred (Girard 121ff.).

Missing this rather central thesis of Girard’s work, Parrish applies the partial insights to

O’Connor, stating that “The Misfit at once murders and redeems the babbling grandmother”

(Parrish 43). However Parrish pushes further, stating that “O’Connor represses” the fact that “the

Misfit’s words figure his own redemption as well as the grandmother’s: if only he could be

shooting someone every minute of her life, then he would be saved as well” (Parrish 43). In this

way, Parrish finds in O’Connor’s fiction the implicit suggestion that violence is more than

merely an agent of redemption, it is also “an expression of the sacred” (Parrish 43). Applying

this insight to our story, this would mean that Pointer’s theft of wooden legs is, for O’Connor,

something both sacred and intrinsically redeeming. Our suggestion is that, while O’Connor’s

fiction may at times imply an ontology that conflicts with her central affirmations, there are some

readings of her work that, in light of O’Connor’s Christian ontology, stretch beyond the limits of

credibility.

VI. Conclusion

O’Connor notes that for the novelist who would seek to use distortion, “The

problem…will be to know how far he can distort without destroying” (MM 50). While

O’Connor would abhor the suggestion, we have argued here that at times, her use of violence,

when issuing in ambiguous results, can indeed suggest an ontology of violence. Yet O’Connor’s

alignment with an ontology of peace, as we have demonstrated, is striking: she doggedly dwells

on the surface of sensible reality, grounds this approach robustly in the Incarnation, and

embraces a theology of analogia entis, whereby the surface participates in and brims with the life

of God. Consequently, inasmuch as O’Connor’s theological view of reality aligns so well with

Carson 27

Hart’s ontology of peace, we might expect that, however off-putting her violent images and

characters might be even for those whose aesthetics have been shaped by a Christian conception

of beauty, her ontology will nonetheless find its way into countless nooks and crannies of her

stories, and succeed in offering, through the violence, a vision of peace.

Bibliography

Atkins, Christine. "Educating Hulga: Re-Writing Seduction in 'Good Country People'." 'on the

Subject of the Feminist Business': Re-Reading Flannery O'Connor. Ed. Teresa Caruso. New

York, NY: Peter Lang, 2004. 120-128.

Auerbach, Erich. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 2003.

Bleikasten, Andre. “The Role of Grace in O’Connor’s Fiction.” Readings on Flannery O’Connor.

San Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2001, 77-82.

Gentry, Marshall Bruce. "How Sacred is the Violence in 'A View of the Woods'?" 'on the Subject

of the Feminist Business': Re-Reading Flannery O'Connor. Ed. Teresa Caruso. New York,

NY: Peter Lang, 2004. 64-73.

Girard, I See Satan Fall Like Lightning. Trans. James G. Williams. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis

Books,

2001.

Hart, David Bentley. “Infinite Lit,” Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity 18: 9 (Nov.

2005): 47-49.

Hart, David Bentley. The Beauty of the Infinite: The Aesthetics of Christian Truth. Grand

Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

Hendin, Josephine. “Violence in O’Connor’s Work.” Readings on Flannery O’Connor. San

Diego: Greenhaven Press, 2001, 83-87.

Kahane, Claire. “the Re-Vision of Rage: Flannery O'Connor and Me.” The Massachusetts

Review 46 (2005): 439-61.

Kinney, Arthur F. Flannery O’Connor’s Library: Resources of Being. Athens, University of

Georgia Press, 1985.

Carson 28

Lynch, William F., S.J. Christ and Apollo: The Dimensions of the Literary Imagination.

Wilmington, DE: ISI Books, 2004.

__________________. “Theology and the Imagination,” Thought 29:112 (Spring 1954): 61-86.

Maritain, Jacques. Art and Scholasticism. J. F. Scanlan, trans. New York: Charles Scribner’s

Sons, 1930.

McEntyre, Marilyn Chandler. “Mercy that Burns: Violence and Revelation in Flannery

O'Connor's Fiction.” Theology Today 53 (1996): p331(14).

McMullen, Joanne Halleran. Writing against God : language as message in the literature of

Flannery O'Connor. Macon, Ga. : Mercer University Press, 1996.

O’Connor, Flannery. The Complete Stories. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971.

___________________. The Habit of Being. Sally Fitzgerald, intro. and ed. New York: Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 1979.

___________________. The Violent Bear it Away (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux,

1988).

___________________. Mystery and Manners. Sally and Robert Fitzgerald, eds. New York:

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969.

Parrish, Tim. "The Killer Wears the Halo: Cormac McCarthy, Flannery O'Connor, and the

American Religion." Sacred Violence, I: Cormac McCarthy's Appalachian Works; II:

Cormac McCarthy's Western Novels. Ed. Wade Hall and Rick Wallach. El Paso, TX: Texas

Western, 2002. 35-50.

Piper, Wendy. “The Hubris of the Sacred Self: Evocations of the Tragic in the Christian Vision

of Flannery O’Connor,” in Flannery O’Connor Review 1 (2001-2002): 26-31.

Raab, Joseph Quinn. "Theology Today; Flannery O'Connor's Art of Conversion.(''Good Country

People'')." 63 (2007): 442(8).

Rosengarten, Richard A. “The Catholic Sophocles: Violence and Vision in Flannery O'Connor's

‘Revelation’.” Religion and Culture Web Forum, November 2003.

Tate, Allen. Essays of Four Decades. Chicago: Swallow Press, 1968.

Westarp, Karl-Heinz. Precision and Depth in Flannery O’Connor’s Short Stories. Arhus: Aarhus

University Press, 2002.

Carson 29

Wood, Ralph C. The Comedy of Redemption: Christian Faith and Comic Vision in Four

American Novelists. Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 1988.

Yaeger, Patricia. “Flannery O’Connor and the Aesthetics of Torture.” Flannery O’Connor:

New Perspectives. Eds. Rath, Sura P. and Mary Neff Shaw. Athens, Georgia: University

of Georgia Press, 1996.

Zuber, Leo J., comp. The Presence of Grace and Other Book Reviews by Flannery O’Connor.

Carter W. Martin, ed. and intro. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1983.

Throughout this paper we will use this word, “surface,” to refer to the whole of sensible reality, but also,

where specified, “surface” will also refer to the rhetorical surface of a text itself; that is to say, to the

sensible reality of the text.

i

Hart notes that “Deleuze, Foucault, and others who adopt language similar to theirs tend to be somewhat

oblivious (or indifferent) to the ways their account of the will to power can easily turn into an

endorsement of, quite precisely, a will to, quite precisely, power. Hart, 69.

ii

iii

Defending himself against claims to innovation here, Hart cites his sources for this ontology in the

Patristics: “My understanding of a Christian ‘ontology of peace’ is something I learned from Gregory of

Nyssa, Augustine, Denys, Maximus and many others; and I am rather of the opinion that the true

ontological implications of high patristic thought have rarely received the appreciation or the deep study

that they merit.” Hart, “Infinite Lit,” 96.

Dostoevsky’s anguish, for instance, over a peasant child who is bound, mouth stuffed with her own

feces, and locked in an outdoor privy to endure a long Russian winter’s night, is simply not a concern for

the high style of classic tragedy. As Hart notes in a response article to critics, the tragic genre of Greek

antiquity treated only of the aristocracy and the high matters of the polis with a necessary gravity:

“I continue to maintain that a serf boy torn apart by hounds, or a little middle-class girl weeping

in an outhouse on a winter’s night, or a village baby murdered by a Turkish soldier would not constitute

subject matter appropriate to the Dionysian stage…they simply lack the requisite quality of tragic

nobility; they could not imbue resignation to fate with the fuliginous glamour necessary for ‘true’

tragedy.”

The real problem with tragedy, says Hart, is that it is not serious enough about the horrors of

suffering and violence: “If we read the gospel within the horizon of tragic necessity, then we find its

power to disturb us and transform our vision of reality diminished; for, as much as Attic tragedy casts a

light upon human suffering, it also glamorizes, beautifies and ritually dissembles both the particularity

and the horror of evil…” Hart, “Infinite Lit,” 100. It is in this sense that tragedy does not take violence

seriously enough, nor can it, because there is a certain necessity and inevitability to it that deadens the

impact of its absurdity and horror.

iv

Given this approach, it is wholly appropriate to compare Hart’s approach to the “surface” of being itself,

and the “surface” of O’Connor’s fictional text. Here we must also recall that part of Hart’s surface of

being is rhetoric, supremely manifest of course in the incarnate Christ. The importance of this emphasis

on the Incarnation will presently be explored.

v

vi

William F. Lynch, S.J. (1908-1987), was a literary scholar, theologian and philosopher, who was

immensely interested in the intersection between imaginative literature and Catholic theology. He was

Carson 30

also the senior editor of Thought from 1950-1956, a leading Catholic journal to which O’Connor

subscribed and read voraciously.

vii

Auerbach, 194-197. Also, it is perhaps quite significant that Lynch himself drew a great deal from

Auerbach’s work. In Christ and Apollo (CA), which O’Connor reviewed, Lynch quotes key sections of

Auerbach’s Mimesis, especially emphasizing the latter’s treatment of Farinata and Calvicante in Dante’s

Inferno. Cf. Lynch’s discussion of Auerbach and Dante’s figural realism in Christ and Apollo, 329-330.

viii

In addition to Lynch, the theologically-minded New Criticism of Allen Tate was also quite influential

in the regard. Everything of importance which Tate wrote was sent to O’Connor by his wife, her good

friend Caroline Gordon. Cf. especially Tate’s essay on “The Angelic Imagination” and its invective

against Manichean and Apollonian sensibilities, in his Essays of Four Decades.

ix

Lynch, CA, 203. Note the similarities between Hart and Lynch, on the idea that the analogy of being

accentuates rather than closes down difference: “Is it true or not that the natural order of things has been

subverted and that there has been a new creation, within which the one, single, narrow form of Christ of

Nazareth is in process of giving its shape to everything? To think and imagine according to this form is to

think and imagine according to a Christic dimension. It would also make every dimension Christic.

However, like analogy itself, this would not destroy difference but would make it emerge even more

sharply.” Lynch, CA, 250 (emphasis original).

O’Connor regularly read the quarterly Catholic journal called Thought, and in response to Elizabeth

Sewell’s 1954 review of Graham Greene’s work, she says in a letter to a friend: “What he [Greene] does. .

. is try to make religion respectable to the modern unbeliever by making it seedy. He succeeds so well in

making it seedy that then he has to save it by the miracle.” Flannery O’Connor, The Habit of Being, 201

(hereafter cited as HB). As for Mauriac, O’Connor responds, in a book review, to an author who equates

Mauriac’s “weakness” of appealing to the miraculous, with Catholic theology. She says: “He considers

this the weakness of Catholic theology generally. To the reviewer it appears strictly a novelistic

weakness.” The review cited here is: The Bulletin, December 23, 1961. Review of The Novelist and the

Passion Story by F.W. Dillistone (Sheed and Ward, 1960), cited in Zuber, 127-128.

x

For the definitive influence of Lynch on this connection, see O’Connor’s review of his Christ and

Apollo in Zuber, 74-75 (The Bulletin, August 8, 1959).

xi

Again, at this point, Lynch’s influence is substantial. This quotation is one of the most heavily analyzed

and discussed passages in O’Connor’s non-fiction. However, few scholars note that, in her review of

Lynch’s Christ and Apollo, O’Connor essentially repeats this quotation. This is no surprise, given

Lynch’s strong emphasis on medieval exegesis, but the influence on O’Connor of his connection between

this exegesis and the literary imagination, has gone far too unnoticed.

xii

It is clear that, while other New Critical influences contributed here, O’Connor gets the ontological

idea for this kind literary symbol again, from William Lynch. Compare his comments here with

O’Connor’s: “For our present purposes, we may roughly and initially describe the analogical as that habit

of perception which sees that different levels of being are also somehow one and can therefore be

associated in the same image, in the same and single act of perception.” Lynch, “Theology and the

Imagination,” 66. In her copy of this article, O’Connor underlined this passage. Kinney, 180.

xiii

This is not, we must emphatically note, to limit interpretation of violence in O’Connor’s fiction to her

stated intentions or beliefs. It is, however, simply to grasp a general sense of how O’Connor viewed

reality, as surely this can indeed guide the range of the interpretive options we entertain, both within and

outside of the umbrella of authorial intention.

xiv

Carson 31

The connections between O’Connor’s capture of mystery and manners in a singular symbol, and the

Incarnation, are evident in a letter she writes to her friend, Betty Hester, on the difficulties of writing for a

secular audience: “One of the awful things about writing when you are a Christian is that for you the

ultimate reality is the Incarnation, the present reality is the Incarnation, the whole reality is the

Incarnation, and nobody believes in the Incarnation; that is, nobody in the audience. My audience are the

people who think God is dead. At least these are the people I am conscious of writing for.” Collected

Writings, 943; cited in Westarp, 9-10.

xv

O’Connor continues her comment here: “If I hadn’t had the Church to fight it with or to tell me the

necessity of fighting it, I would be the stinkingest logical positivist you ever saw right now. With such a

current to write against, the result almost has to be negative. It does well just to be.” 28 August 55, Letter

to “A”, HB 97

xvi

xvii

A related, and important question here, is to ask for whom is the violence redemptive? Oftentimes

different O’Connor scholars object to the idea of “redemptive” or “sacred” violence, on the premise that

senseless violence is still, regardless of whatever “redemption” takes place, pervasive throughout

O’Connor’s stories. For instance, Gentry questions whether the violence in “A View to the Woods” is

indeed “sacred” at all, given that at the end of the story, an abusive father continues to have his way with

his children. This misses the point that the possibility of redemption through the suffering of violence, is

focused on Mary Pitts. Gentry, 72.

In the baptismal scene of The Violent Bear it Away, for instance, Tarwater’s plan, under the influence

of a devil figure, is to drown the dimwit boy Bishop and thus repudiate his [Tarwater’s] inextirpable

prophetic calling. Tarwater succeeds, of course, in drowning the boy, but as he does so he finds himself

unable to resist uttering the words of baptismal institution. There is no indication in this scene, that

Tarwater has accepted a kind of offer of grace. Rather, this is one instance in which grace breaks in upon

him and compels his complicity. O’Connor, The Violent Bear it Away, 209-210, 221.

xviii

For an excellent example of this, see Girard’s recounting of an ancient Ephesian purging of citywide

disease and discord through the stoning of a beggar. Girard, 49ff.

xix

xx

We will presently examine the way in which Josephine Hendin makes precisely this move.

xxi

What, one wonders, might Atkins mean by the word “redemption?”

MM, 111. For the insight of connecting O’Connor’s dramatic action to Greek tragedy, I am indebted to

Piper and Rosengarten. Piper notes that O’Connor prepares the reader for the central dramatic action in

which grace is offered to a character by means of, among other things, the gradual accumulation of

concrete images which bolster the final anagogical epiphanic moment: “Thus The Misfit appears on the

first page of ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’; the exposed beams in the attic cast foreboding shadows long

before Norton hangs himself in ‘The Lame Shall Enter First’; and in The Violent Bear it Away, the

continual presence of water early in the novel signals Bishop’s fatal baptism.” Piper, 28.

xxii

MM, 100. O’Connor adds, “when I found out that this was what was going to happen, I realized that it

was inevitable. This is a story that produces a shock for the reader, and I think one reason is that it

produced a shock for the writer.”

xxiii

We must note here, however, that not all of O’Connor’s literary moments are an attempt to do this;

some moments will imply contact with mystery, grace, and the violence associated with this, while others

xxiv

Carson 32

appear simply to be a depiction of violent, sensible reality. A good example of this is found in

O’Connor’s story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” The focus of the contact between the literal level of the

text and an additional register of “mystery” is focused around the interaction between the Misfit and the

grandmother, and the latter’s sudden murder at the hands of the former. On the periphery of this central

action, all the members of the grandmother’s family have been shot and killed in the woods. Their deaths

are not the symbolic occasion for O’Connor’s attempted connection of the literal level with mystery or

with grace. They simply die. It is notable that their deaths are not described, and only occur off the side of

the page, as it were.

However, although O’Connor suggests that her readers “be on the lookout for…the action of

grace in the Grandmother’s soul, and not for the dead bodies” (MM, 113), it is still appropriate to ask

what the dead bodies suggest about O’Connor’s overall view of violence. The typical problem that arises

among O’Connor critics is that theological interpretations, in their focus on the Grandmother’s moment of

“grace” (which in itself is debatably something other than grace), ignore the surd quality of evil to which

the senseless murders attest. It is precisely the bypassing of the dead bodies which most anti-theological

interpreters protest, and rightly so, in our view. The problem with these protestors, however, is their

exclusion of any moments of “grace” in the text, since they do not share O’Connor’s view that the

sensible, even the rhetorical, can participate in the mystery and life of God.

As Ralph C. Wood suggests, a “classic natural theology built on our native desire for God is, in

O’Connor’s view, no longer possible” (Wood, 81). This is not to say that nature is no longer graced or

that the natural desire for God is eradicated; it is rather to emphasize the utter vacuity of the modern

situation. But even given this state of things, the desire for God manifests itself. Even in their frontal

denial of God, her characters, such as Hazel Motes in Wise Blood or Francis Tarwater in The Violent

Bear it Away, remain obsessed with Him, and are marked with a desire for the transcendent which cannot

be muted or stilled.

xxv

However O’Connor does succeed with some of her metaphors. For instance, Manley Pointer’s hat

successfully serves, as in other stories by O’Connor, to an indicate his evil or demonic role. The Misfit in

“A Good Man is Hard to Find” is the most famous example of this typical use of hats, and in this story we

find that the villain, Manley Pointer, dons a hat when he meets up with Hulga, intent on stealing her leg.

Notably, the narrative action slows down at this point in order to focus on the hat, its colors and detail.

O’Connor adds a nice touch of foreshadowing, as Hulga “wondered if he had brought it for the occasion”

(287). In addition, even when he is kissing Hulga later on, “he did not remove his hat but it was pushed

far enough back not to interfere,” though tellingly, Hulga’s glasses do get in the way, so he slips them

into his pocket (287).

xxvi

xxvii

McMullen includes a list of words that, in context, have negative connotations: illusions, nowhere,

empty, blindfolds, losing, escaping, detached, distance, destroy, surrendering, escaping, forgetting,

doubted, abashed, unusual, unexceptional, uncertain, blankly, mesmerized, different. McMullen, 102.