Cause of the Crusades - Madison County Schools

advertisement

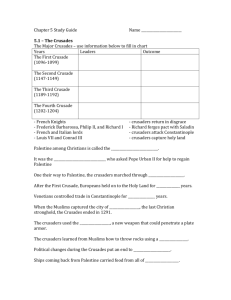

Cause of the Crusades The reason and cause of the crusades was a war between Christians and Moslems which centered on the city of Jerusalem and the Holy places of Palestine. The City of Jerusalem held a Holy significance to the Christian religion. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem commemorated the hill of crucifixion and the tomb of Christ's burial. Pilgrims throughout the Middle Ages made sacred pilgrimages to the Holy city of Jerusalem and the church. Although the city of Jerusalem was held by the Saracens the Christian pilgrims had been granted safe passage to visit the Holy city. In 1065 Jerusalem was taken by the Turks, who came from the kingdom of ancient Persia. 3000 Christians were massacred and the remaining Christians were treated so badly that throughout Christendom people were stirred to fight in crusades. These actions aroused a storm of indignation throughout Europe and awakened the desire to rescue the Holy Land from the grasp of the "infidel." Cause of the Crusades - 3000 Christian Pilgrims massacred in Jerusalem Among the early Christians it was thought a pious and meritorious act to undertake a journey to some sacred place. Especially was it thought that a pilgrimage to the land that had been trod by the feet of the Savior of the world, to the Holy City that had witnessed his martyrdom, was a peculiarly pious undertaking, and one which secured for the pilgrim the special favor and blessing of Heaven. The Saracen caliphs, for the four centuries and more that they held possession of Palestine, pursued usually an enlightened policy towards the pilgrims, even encouraging pilgrimages as a source of revenue. But in the eleventh century the Seljukian Turks, a prominent Tartar tribe and zealous followers of Islam, wrested from the caliphs almost all their Asiatic possessions. The Christians were not long in realizing that power had fallen into new hands. 3000 Christian Pilgrims were insulted and persecuted in every way. The churches in Jerusalem were destroyed or turned into stables. Cause of the Crusades - Religious Conviction If it were a meritorious thing to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre, much more would it be a pious act to rescue the sacred spot from the profanation of infidels. This was the conviction that changed the pilgrim into a warrior, this was the sentiment that for two centuries and more stirred the Christian world to its profoundest depths, and cast the population of Europe in wave after wave upon Asia. Cause of the Crusades - The Instinct to Fight Although this religious feeling was the principal cause of the Crusades, still there was another concurring cause which must not be overlooked. This was the restless, adventurous spirit of the Teutonic peoples of Europe, who had not as yet outgrown their barbarian instincts. The feudal knights and lords, just now animated by the rising spirit of chivalry, were very ready to enlist in an undertaking so consonant with their martial feelings and their new vows of knighthood. Cause of the Crusades - The Preaching of Peter the Hermit The immediate cause of the First Crusade was the preaching of Peter the Hermit, a native of Picardy, in France. Having been commissioned by Pope Urban II. to preach a crusade, the Hermit traversed all Italy and France, addressing everywhere, in the church, in the street, and in the open field, the crowds that flocked about him, moving all hearts with sympathy or firing them with indignation, as he recited the sufferings of their brethren at the hands of the infidels, or pictured the profanation of the holy places, polluted by the presence and insults of the unbelievers. Cause of the Crusades - The Threat of the Turks Whilst Peter the Hermit had been arousing the warriors of the West, the Turks had been making constant advances in the East, and were now threatening Constantinople itself. The Greek emperor (Alexius Comnenus) sent urgent letters to the Pope, asking for aid against the infidels, representing that, unless assistance was extended immediately, the capital with all its holy relics must soon fall into the hands of the barbarians. Cause of the Crusades - Pope Urban II & the Council of Clermont Pope Urban II called a great council of the Church at Placentia, in Italy, to consider the appeal (1095), but nothing was effected. Later in the same year a new council was convened at Clermont, in France, Pope Urban purposely fixing the place of meeting among the warm tempered and martial Franks. Pope Urban II himself was one of the chief speakers. He was naturally eloquent, so that the man, the cause, and the occasion all conspired to achieve one of the greatest triumphs of human oratory. Pope Urban II pictured the humiliation and misery of the provinces of Asia; the profanation of the places made sacred by the presence and footsteps of the Son of God. Pope Urban II then detailed the conquests of the Turks, until now, with all Asia Minor in their possession, they were threatening Europe from the shores of the Hellespont. Cause of the Crusades - "It is the will of God" "When Jesus Christ summons you to his defense," exclaimed the eloquent pontiff, "let no base affection detain you in your homes; whoever will abandon his house, or his father, or his mother, or his wife, or his children, or his inheritance, for the sake of my name, shall be recompensed a hundred-fold, and possess life eternal." Here the enthusiasm of the vast assembly burst through every restraint. With one voice they cried, "Dieu le volt! Dieu le volt!" meaning "It is the will of God! It is the will of God!" Thousands immediately affixed the cross to their garments as a pledge of their sacred engagement to go forth to the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre. The fifteenth day of August of the following year (1096) was set for the departure of the expedition - the Crusades had begun. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/cause-of-crusades.htm Holy Land Pilgrimage The crusades were first and foremost a spiritual enterprise. They sprang from the pilgrimages which Christians had long been accustomed to make to the scenes of Christ's life on earth. Men considered it a wonderful privilege to see the cave in which He was born, to kiss the spot where He died, and to kneel in prayer at His tomb. The eleventh century saw an increased zeal for pilgrimages, and from this time travelers to the Holy Land were very numerous. For greater security they often joined themselves in companies and marched under arms. It needed little to transform such pilgrims into crusaders. Holy Land Pilgrimage - Abuse of the pilgrims by the Turks The Arab conquest of the Holy Land had not interrupted the stream of pilgrims, for the early caliphs were more tolerant of unbelievers than Christian emperors of heretics. But after the coming of the Seljuk Turks into the East, pilgrimages became more difficult and dangerous. The Turks were a ruder people than the Arabs whom they displaced, and in their fanatic zeal for Islam were not inclined to treat the Christians with consideration. Many tales floated back to Europe of the outrages committed on the pilgrims and on the sacred shrines venerated by all Christendom. Such stories, which lost nothing in the telling, aroused a storm of indignation throughout Europe and awakened the desire to rescue the Holy Land from the grasp of the "infidel." Holy Land Pilgrimage - The Christian and Infidel in the Holy Land The ranks of the crusaders were constantly filled by fresh bands of pilgrim knights who visited Palestine to pray at the Holy Sepulcher and cross swords with the infidel. In spite of constant border warfare much trade and friendly intercourse prevailed between Christians and Moslems. They learned to respect one another both as foes and neighbors. The crusaders' states in Syria became a meeting-place of East and West. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/holy-land-pilgrimage.htm The First Crusade - 1096 - 1099 A brief description and outline of the Cause of the Crusades is as follows: The massacre of 3000 Christian Pilgrims in Jerusalem prompted the first crusade Religious Conviction of crusaders The Instinct to Fight The Preaching of Peter the Hermit The Threat of the Turks The Council of Clermont led by Pope Urban II - "It is the will of God" Leaders of the First Crusade The leaders of the First Crusade included some of the most distinguished representatives of European knighthood. Count Raymond of Toulouse headed a band of volunteers from Province in southern France. Godfrey of Bouillon and his brother Baldwin commanded a force of French and Germans from the Rhineland. Normandy sent Robert, William the Conqueror's eldest son. The Normans from Italy and Sicily were led by Bohemond, a son of Robert Guiscard, and his nephew Tancred. The First Crusade - The People's Crusade The months which followed the Council of Clermont were marked by an epidemic of religious excitement in western Europe. Popular preachers everywhere took up the cry "God wills it!" and urged their hearers to start for Jerusalem. A monk named Peter the Hermit aroused large parts of France with his passionate eloquence, as he rode from town to town, carrying a huge cross before him and preaching to vast crowds. Without waiting for the main body of nobles, which was to assemble at Constantinople in the summer of 1096 a horde of poor men, women, and children set out, unorganized and almost unarmed, on the road to the Holy Land. This was called the Peoples Crusade, it is also referred to as the Peasants Crusade. Dividing command of the mixed multitudes with a poor knight, called Walter the Penniless, and followed by a throng of about 80,000 persons, among whom were many women and children, Peter the Hermit set out for Constantinople leading the Peoples Crusade via an overland route through Germany and Hungary. Thousands of the Peoples Crusade fell in battle with the natives of the countries through which they marched, and thousands more perished miserably of hunger and exposure. The Peoples Crusade was badly organized - most of the people were unarmed and lacked the command and discipline of the military crusaders. The Byzantium emperor Alexius I sent his ragged allies as quickly as possible to Asia Minor, where most of them were slaughtered by the Turks. The daughter of Alexius, called Anna Comnena wrote a book about her father and the crusaders called the Alexiad which provides historical details about the first crusaders. Those crusaders who crossed the Bosphorus were surprised by the Turks, and almost all of the Peoples Crusade were slaughtered. Peter the Hermit did survive and eventually led the Crusaders in a procession around the walls of Jerusalem just before the city was taken. The Main Body of the First Crusade Meanwhile real armies were gathering in the West. Recruits came in greater numbers from France than from any other country, a circumstance which resulted in the crusaders being generally called "Franks" by their Moslem foes. They had no single commander, but each contingent set out for Constantinople by its own route and at its own time. The First Crusade - The Siege of Antioch Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lorraine, and Tancred, "the mirror of knighthood," were among the most noted of the leaders of the different divisions of the army. The expedition numbered about 700,000 men, of whom fully 100,000 were mailed knights. The crusaders traversed Europe by different routes and reassembled at Constantinople. Crossing the Bosphorus, they first captured Nicaea, the Turkish capital, in Bithynia, and then set out across Asia Minor for Syria. Arriving at Antioch, the survivors captured that place, and then, after some delays, pushed on towards Jerusalem. The Siege of Antioch had lasted from October 1097 to June 1098. The First Crusade - The City of Jerusalem Reduced now to perhaps one-fourth of their original numbers, the crusaders advanced slowly to the city which formed the goal of all their efforts. When at length the Holy City burst upon their view, a perfect delirium of joy seized the crusaders. They embraced one another with tears of joy, and even embraced and kissed the ground on which they stood. As they passed on, they took off their shoes, and marched with uncovered head and bare feet, singing the words of the prophet: "Jerusalem, lift up thine eyes, and behold the liberator who comes to break thy chains." Before attacking it they marched barefoot in religious procession around the walls, with Peter the Hermit at their head. Then came the grand assault. The First Crusade - The Capture of Jerusalem The first assault made by the Christians upon the walls of the city was repulsed; but the second was successful, and the city was in the hands of the crusaders by July 1099. Godfrey of Bouillon and Tancred were among the first to mount the ramparts. Once inside the city, the crusaders massacred their enemies without mercy. A terrible slaughter of the infidels took place. For seven days the carnage went on, at the end of which time scarcely any of the Moslem faith were left alive. The Christians took possession of the houses and property of the infidels, each soldier having a right to that which he had first seized and placed his mark upon. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/the-first-crusade.htm The Second Crusade - 1147 - 1149 The success of the Christians in the First Crusade had been largely due to the disunion among their enemies. But the Moslems learned in time the value of united action, and in 1144 A.D. succeeded in capturing Edessa, one of the principal Christian outposts in the East. The fall of the city of Edessa, followed by the loss of the entire county of Edessa, aroused western Europe to the danger which threatened the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and led to another crusading enterprise. The Second Crusade and the Origin of the Religious Orders of Knighthood In the interval between the Second and the Third Crusade, the two famed religious military orders, known as the Hospitallers and the Templars, were formed. A little later, during the Third Crusade, still another fraternity, known as the Teutonic Knights was established. The objects of all the orders were the care of the sick and wounded crusaders, the entertainment of Christian pilgrims, the guarding of the holy places, and ceaseless battling for the Cross. These fraternities soon acquired a military fame that was spread throughout the Christian world. They were joined by many of the most illustrious knights of the West, and through the gifts of the pious acquired great wealth, and became possessed of numerous estates and castles in Europe as well as in Asia. Religious Knights Teutonic Knights Knights Hospitaller Templar Knights The Cause of the Second Crusade - The Fall and Massacre at Edessa In the year 1146, the city of Edessa, the bulwark of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem on the side towards Mesopotamia, was taken by the Turks, and the entire population was slaughtered, or sold into slavery. This disaster threw the entire West into a state of the greatest alarm, lest the little Christian state, established at such cost of tears and suffering, should be completely overwhelmed, and all the holy places should again fall into the hands of the infidels. The Second Crusade - The Preaching of St. Bernard The apostle of the Second Crusade was the great abbot of Clairvaux, St. Bernard. Scenes of the wildest enthusiasm marked his preaching. The scenes that marked the opening of the First Crusade were now repeated in all the countries of the West. St. Bernard, an eloquent monk, was the second Peter the Hermit, who went everywhere, arousing the warriors of the Cross to the defense of the birthplace of their religion. When the churches were not large enough to hold the crowds which flocked to hear him, he spoke from platforms erected in the fields. The Second Crusade & King Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany The contagion of the holy enthusiasm seized not only barons, knights, and the common people, which classes alone participated in the First Crusade, but kings and emperors were now infected with the sacred frenzy. St. Bernard's eloquence induced two monarchs, Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, to take the blood-red cross of a crusader. Conrad III., emperor of Germany, was persuaded to leave the affairs of his distracted empire in the hands of God, and consecrate himself to the defense of the sepulcher of Christ. Louis VII., king of France, was led to undertake the crusade through remorse for an act of great cruelty that he had perpetrated upon some of his revolted subjects. The Failure of the Second Crusade The Second Crusade, though begun under the most favorable auspices, had an unhappy ending. Of the great host that set out from Europe, only a few thousands escaped annihilation in Asia Minor at the hands of the Turks. Louis and Conrad, with the remnants of their armies, made a joint attack on Damascus, but had to raise the siege after a few days. This closed the crusade. As a chronicler of the expedition remarked, "having practically accomplished nothing, the inglorious ones returned home." The strength of both the French and the German division of the expedition was wasted in Asia Minor, and the crusade accomplished nothing. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/the-second-crusade.htm The Third Crusade 1189 - 1192 Not many years after the Second Crusade, the Moslem world found in the famous Saladin a leader for a holy war against the Christians. Saladin in character was a typical Mohammedan, very devout in prayers and fasting, fiercely hostile toward unbelievers, and full of the pride of race. To these qualities he added a kindliness and humanity not surpassed, if equaled, by any of his Christian foes. The Third Crusade was caused by the capture of Jerusalem in 1187 by Saladin, the sultan of Egypt. The capture of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187 Having made himself sultan of Egypt, Saladin united the Moslems of Syria under his sway and then advanced against the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Christians met him in a great battle near the lake of Galilee. It ended in the rout of their army and the capture of their king. Even the Holy Cross, which they had carried in the midst of the fight, became the spoil of the conqueror. Saladin quickly reaped the fruits of victory. The Christian cities of Syria opened their gates to him, and at last Jerusalem itself surrendered after a short siege. Little now remained of the possessions which the crusaders had won in the East. The Third Crusade is organized The news of the taking of Jerusalem spread consternation throughout western Christendom. The cry for another crusade arose on all sides. Once more thousands of men sewed the cross in gold, or silk, or cloth upon their garments and set out for the Holy Land. When the three greatest rulers of Europe - King Philip Augustus of France, King Richard I of England, and the German emperor, Frederick Barbarossa assumed the cross, it seemed that nothing could prevent the restoration of Christian supremacy in Syria. These great rulers set out, each at the head of a large army, for the recovery of the Holy City of Jerusalem. Biography of Richard the Lionheart King Richard raises Money for the Third Crusade King Richard I of England (afterwards given the title of 'Coeur de Lion', the "Lion-hearted," in memory of his heroic exploits in Palestine) was the central figure among the Christian knights of this crusade. He raised money for the enterprise by the persecution and robbery of the Jews the imposition of an unusual tax upon all classes the sale of offices, dignities, and the royal lands When some one expostulated with him on the means employed to raise money, he declared that "he would sell the city of London, if he could find a purchaser." The Death of Frederick Barbarossa, the German Emperor The German crusaders, attempting the overland route, was consumed in Asia Minor by the hardships of the march and the swords of the Turks. The Germans under Frederick Barbarossa were the first to start. This great emperor was now nearly seventy years old, yet age had not lessened his crusading zeal. The Emperor Frederick, according to the most probable accounts, was drowned while crossing a swollen stream, and the most of the survivors of his army, disheartened by the loss of their leader, returned to Germany. The Third Crusade - the Siege of Acre The English and French kings finally mustered their forces beneath the walls of Acre, which city the Christians were then besieging. It is estimated that 600,000 men were engaged in the investment of the place. After one of the longest and most costly sieges they ever carried on in Asia, the crusaders at last forced the place to capitulate, in spite of all the efforts of Saladin to render the garrison relief. The Third Crusade - the Capture of Acre in 1191 The expedition of the French and English achieved little, other than the capture of Acre. Philip and Richard, who came by sea, captured Acre after a hard siege, but their quarrels prevented them from following up this initial success. King Philip soon went home, leaving the further conduct of the crusade in Richard's hands. The Third Crusade - King Richard and Saladin The knightly adventures and chivalrous exploits which mark the career of Richard in the Holy Land read like a romance. Nor was the chief of the Mohammedans, the renowned Saladin, lacking in any of those knightly virtues with which the writers of the time invested the character of the English hero. At one time, when Richard was sick with a fever, Saladin, knowing that he was poorly supplied with delicacies, sent him a gift of the choicest fruits of the land. And on another occasion, Richard's horse having been killed in battle, the sultan caused a fine Arabian steed to be led to the Christian camp as a present for his rival. For two years did Richard the Lion-hearted vainly contend in almost daily combat with his generous antagonist for the possession of the tomb of Christ. King Richard in the Holy Land 1191 - 1192 The English king remained in the Holy Land. His campaigns during this time gained for him the title of "Lion-hearted," by which he is always known. He had many adventures and performed knightly exploits without number, but could not capture Jerusalem. Tradition declares that when, during a truce, some crusaders went up to Jerusalem, Richard refused to accompany them, saying that he would not enter as a pilgrim the city which he could not rescue as a conqueror. The Truce between King Richard and Saladin The English king remained for longer in the Holy Land than the other leaders. King Richard and Saladin finally concluded a truce by the terms of which Christians were permitted to visit Jerusalem without paying tribute, that they should have free access to the holy places, and remain in undisturbed possession of the coast from Jaffa to Tyre. King Richard then set sail for England, and with his departure from the Holy Land the Third Crusade came to an end. The Ransom of King Richard King Richard on his return from the Holy Land was shipwrecked off the coast of the Adriatic. Attempting to travel through Austria in disguise, he was captured by the duke of Austria, whom he had offended at the siege of Acre. The king regained his liberty only by paying a ransom equivalent to more than twice the annual revenues of England. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/the-third-crusade.htm The Fourth Crusade - 1202 - 1261 The real author of the Fourth Crusade was the famous pope, Innocent III. Young, enthusiastic, and ambitious for the glory of the Papacy, he revived the plans of Pope Urban II and sought once more to unite the forces of Christendom against Islam. No emperor or king answered his summons, but a number of knights (chiefly French) took the crusader's vow. None of the Crusades, after the Third, effected much in the Holy Land; either their force was spent before reaching it, or they were diverted from their purpose by different objects and ambitions. The crusaders of the Fourth expedition captured Constantinople instead of Jerusalem. The Fourth Crusade - The Crusaders and the Venetians The leaders of the crusade decided to make Egypt their objective point, since this country was then the center of the Moslem power. Accordingly, the crusaders proceeded to Venice, for the purpose of securing transportation across the Mediterranean. The Venetians agreed to furnish the necessary ships only on condition that the crusaders first seized Zara on the eastern coast of the Adriatic. Zara was a Christian city, but it was also a naval and commercial rival of Venice. In spite of the pope's protests the crusaders besieged and captured the city. Even then they did not proceed against the Moslems. The Venetians persuaded them to turn their arms against Constantinople. The possession of that great capital would greatly increase Venetian trade and influence in the East; for the crusading nobles it held out endless opportunities of acquiring wealth and power. Thus it happened that these soldiers of the Cross, pledged to war with the Moslems, attacked a Christian city, which for centuries had formed the chief bulwark of Europe against the Arab and the Turk. The Fourth Crusade - The Sack of Constantinople in 1204 The crusaders, now better styled the invaders, took Constantinople by storm. No "infidels" could have treated in worse fashion this home of ancient civilization. They burned down a great part of it; they slaughtered the inhabitants; they wantonly destroyed monuments, statues, paintings, and manuscripts - the accumulation of a thousand years. Much of the movable wealth they carried away. Never, declared an eye-witness of the scene, had there been such plunder since the world began. The Fourth Crusade - The Wealth of Constantinople The victors hastened to divide between them the lands of the Roman Empire in the East. Venice gained some districts in Greece, together with nearly all the Aegean islands. The chief crusaders formed part of the remaining territory into the Latin Empire of Constantinople. It was organized in fiefs, after the feudal manner. There was a prince of Achaia, a duke of Athens, a marquis of Corinth, and a count of Thebes. Baldwin, Count of Flanders, was crowned Emperor of the East. Large districts, both in Europe and Asia, did not acknowledge, however, these "Latin" rulers. The new empire lived less than sixty years. At the end of this time the Greeks returned to power. Consequences of the Fourth Crusade Constantinople, after the Fourth Crusade, declined in strength and could no longer cope with the barbarians menacing it. Two centuries later the city fell an easy victim to the Turks. The responsibility for the disaster which gave the Turks a foothold in Europe rests on the heads of the Venetians and the French nobles. Their greed and lust for power turned the Fourth Crusade into a political adventure. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/the-fourth-crusade.htm The Children’s Crusade - 1212 The so-called Children's Crusade illustrates at once the religious enthusiasm and misdirected zeal which marked the whole crusading movement. During the interval between the Fourth and the Fifth Crusade, the epidemical fanaticism that had so long agitated Europe seized upon the children, resulting in what is known as the Children's Crusade. The Children’s Crusade - Stephen of Cloyes The preacher of the Children's crusade was a child about twelve years of age, a French peasant lad, named Stephen of Cloyes, who became persuaded that Jesus Christ had commanded him to lead a crusade of children to the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre. The children became wild with excitement, and flocked in vast crowds to the places appointed for rendezvous. Nothing could restrain them or thwart their purpose. "Even bolts and bars," says an old chronicler, "could not hold them." The movement excited the most diverse views. Some declared that it was inspired by the Holy Spirit, and quoted such Scriptural texts as these to justify the enthusiasm: "A child shall lead them;" "Out of the mouth of babes and sucklings thou hast ordained praise." Others, however, were quite as confident that the whole thing was the work of the Devil. The great majority of those who collected at the rallying places were boys under twelve years of age, but there were also many girls. The French Children’s Crusade During the year 1212 A.D. about 30,000 French children assembled in bands and marched through the towns and villages, carrying banners, candles, and crosses and singing, "Lord God, exalt Christianity. Lord God, restore to us the true cross." The French children, set out from the place of rendezvous for Marseilles. Those that sailed from that port were betrayed, and sold as slaves in Alexandria and other Mohammedan slave markets. The children could not be restrained at first, but finally hunger compelled them to return home. The German Children’s Crusade In Germany, during the same year, a lad named Nicholas really did succeed in launching a crusade. He led a mixed multitude of men and women, boys and girls totaling 50,000 in number, over the Alps into Italy, where they expected to take ship for Palestine. From Brundusium 2000 or 3000 of the little crusaders sailed away into oblivion. Not a word ever came back from them. Many other children perished of hardships, many were sold into slavery, and only a few ever saw their homes again. "These children," Pope Innocent III declared, "put us to shame; while we sleep they rush to recover the Holy Land." The Children’s Crusade marked the decline of the Crusades This remarkable spectacle of the children's crusade affords the most striking exhibition possible of the ignorance, superstition, and fanaticism that characterized the period. Yet we cannot but reverence the holy enthusiasm of an age that could make such sacrifices of innocence and helplessness in obedience to what was believed to be the will of God. The children's expedition marked at once the culmination and the decline of the crusading movement. The fanatic zeal that inspired the first crusaders was already dying out. "These children," said the Pope, referring to the young crusaders, "reproach us with having fallen asleep, whilst they were flying to the assistance of the Holy Land." http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/the-childrens-crusade.htm Minor Crusades None of the Crusades, after the Third, effected much in the Holy Land; either their force was spent before reaching it, or they were diverted from their purpose by different objects and ambitions. The crusaders of the Fourth expedition captured Constantinople instead of Jerusalem! The children's crusade affords the most striking exhibition possible of the ignorance, superstition, and fanaticism that characterized the period. The fanatic zeal that inspired the first crusaders was already dying out. But other Crusades were mounted - referred to as the Minor Crusades The Minor Crusades Timeline The Minor Crusades include the following dates and events Minor Crusades Dates of Crusade Fifth Crusade 1217 - 1221 Sixth Crusade 1228 - 1229 Seventh Crusade 1248 - 1254 Eighth Crusade 1270 Ninth Crusade 1271 - 1272 Minor Crusades Timeline of Events The 5th Crusade led by King Andrew II of Hungary, Duke Leopold VI of Austria, John of Brienne The 6th Crusade led by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II The 7th Crusade led by King Louis IX of France The 8th Crusade led by Louis IX The 9th Crusade led by Prince Edward (later Edward I of England) The Minor Crusades The last four expeditions, the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth and Ninth crusades were undertaken by the Christians of Europe against the infidels of the East, may be conveniently grouped as the Minor Crusades. The Minor Crusades were marked by a less fervid and holy enthusiasm than that which characterized the first movements, and exhibit among those taking part in them the greatest variety of objects and ambitions. The Fifth Crusade The Fifth Crusade (1216-1220) was led by the kings of Hungary and Cyprus. Its strength was wasted in Egypt, and it resulted in nothing The Sixth Crusade The Sixth Crusade (1227-1229), headed by Frederick II. of Germany, succeeded in securing from the Saracens the restoration of Jerusalem, together with several other cities of Palestine. The Seventh Crusade The Seventh Crusade (1249-1254) was under the lead of Louis IX. Of France, surnamed the Saint. The Eighth Crusade The Eighth Crusade ( 1270 ) was incited by the fresh misfortunes that, towards the close of the thirteenth century, befell the Christian kingdom in Palestine. The leader of the eighth crusade was King Louis IX of France. King Louis IX directed his forces against the Moors about Tunis, in North Africa. Here the king died of the plague. Nothing was effected by this crusade. The Ninth and Last Crusade The Ninth Crusade (1271 - 1272) was also incited by the misfortunes that, towards the close of the thirteenth century, befell the Christian kingdom in Palestine. The leader of this crusade was Prince Edward of England, afterwards King Edward I. The English prince, was, however, more fortunate than the ill-fated King Louis IX. Edward succeeded in capturing Nazareth, and in compelling the sultan of Egypt to agree to a treaty favorable to the Christians in the Last Crusade . The Last Crusade The flame of the Crusades had burned itself out leading to the Last Crusade. The fate of the little Christian kingdom in Asia, isolated from Europe, and surrounded on all sides by bitter enemies, became each day more and more apparent. Finally the last of the places (Acre) held by the Christians fell before the attacks of the Mamelukes of Egypt, and with this event the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem came to an end (1291). The second great combat between Mohammedanism and Christianity was over, and "silence reigned along the shore that had so long resounded with the world's debate." http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/minor-crusades.htm he End of the Medieval Crusades The crusading movement came to an end by the close of the thirteenth century. The emperor Frederick II for a short time recovered Jerusalem by a treaty, but in 1244 A.D. the Holy City became again a possession of the Moslems. They have never since relinquished it. Acre, the last Christian post in Syria, fell in 1291 A.D., and with this event the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem ceased to exist. The Hospitallers, or Knights of St. John, still kept possession of the important islands of Cyprus and Rhodes, which long served as a barrier to Moslem expansion over the Mediterranean. The Results of the end of the Medieval Crusades The crusades, judged by what they set out to accomplish, must be accounted an inglorious failure. After two hundred years of conflict, after a vast expenditure of wealth and human lives, the Holy Land remained in Moslem hands. It is true that the First Crusade did help, by the conquest of Syria, to check the advance of the Turks toward Constantinople. But even this benefit was more than undone by the weakening of the Roman Empire in the East as a result of the Fourth Crusade. Reasons why the Crusades Failed Reasons why the crusades failed. Of the many reasons for the failure of the crusades, three require special consideration. In the first place, there was the inability of eastern and western Europe to cooperate in supporting the holy wars. A united Christendom might well have been invincible. But the bitter antagonism between the Greek and Roman churches effectually prevented all unity of action. The emperors at Constantinople, after the First Crusade, rarely assisted the crusaders and often secretly hindered them. In the second place, the lack of sea-power, as seen in the earlier crusades, worked against their success. Instead of being able to go by water directly to Syria, it was necessary to follow the long, overland route from France or Germany through Hungary, Bulgaria, the territory of the Roman Empire in the East, and the deserts and mountains of Asia Minor. The armies that reached their destination after this toilsome march were in no condition for effective campaigning. In the third place, the crusaders were never numerous enough to colonize so large a country as Syria and absorb its Moslem population. They conquered part of Syria in the First Crusade, but could not hold it permanently in the face of determined resistance. Why the Crusades ended Why the Crusades stopped. In spite of the above reasons the Christians of Europe might have continued much longer their efforts to recover the Holy Land, had they not lost faith in the movement. But after two centuries the old crusading enthusiasm died out, the old ideal of the crusade as "the way of God" lost its spell. Men had begun to think less of winning future salvation by visits to distant shrines and to think more of their present duties to the world about them. They came to believe that Jerusalem could best be won as Christ and the Apostles had won it "by love, by prayers, and by the shedding of tears." http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/end-of-medieval-crusades.htm The Founding of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem In 1099 Crusaders led by Godfrey of Bouillon, Duke of Lower Lorraine, took Jerusalem back from the Turks. No sooner was Jerusalem in the hands of the crusaders than they set themselves to the task of organizing a government for the city and country they had conquered. The government which they established was a sort of feudal league, known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Kingdom of Jerusalem came into being with the capture of Jerusalem in July of 1099. The new kingdom contained nearly a score of fiefs, whose lords made war, administered justice, and coined money, like independent rulers. The main features of European feudalism were thus transplanted to Asiatic soil. The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and other Crusader States The winning of Jerusalem and the district about it formed hardly more than a preliminary stage in the conquest of Syria. Much fighting was still necessary before the crusaders could establish themselves firmly in the country. Instead of founding one strong power in Syria, they split up their possessions into the three principalities of Tripoli Antioch Edessa These small states of Tripoli, Edessa and Antioch owed allegiance to the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Godfrey of Bouillon and the Kingdom of Jerusalem At the head of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem was placed Godfrey of Bouillon, the most valiant and devoted of the crusader knights of the Knights Templar order. Godfrey of Bouillon refused the title and vestments of royalty, declaring that he would never wear a crown of gold in the city where his Lord and Master had worn a crown of thorns. The only title he would accept was that of "Defender of the Holy Sepulchre." Many of the crusaders, considering their vows fulfilled, now set out on their return to their homes, some making their way back by sea and some by land. Godfrey, Tancred, and a few hundred other knights, were all that stayed behind to maintain the conquests that had been made, and to act as guardians of the holy places. Baldwin of Boulogne the first King of Jerusalem Baldwin of Boulogne was one of the leaders of the First Crusade, who became count of Edessa and then the first titled king of Jerusalem. He was the brother of Godfrey of Bouillon. After Godfrey's death, in July of 1100, Baldwin was invited to Jerusalem by the supporters of a secular monarchy. Baldwin was crowned the first king of Jerusalem on Christmas Day. The coronation took place in Bethlehem. Baldwin the first crowned ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem died on April 2, 1118. His cousin Baldwin of Bourcq was chosen as his successor, although the kingdom was also offered to Eustace III, who did not want it. The Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem On July 4, 1187, the army of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was utterly destroyed by Saladin at the Battle of Hattin. Saladin then overran the entire Kingdom, except for the port of Tyre. Richard the Lionheart recaptured many of the cities in the Kingdom but the Kingdom of Jerusalem was forced to move its capital from Jerusalem to Acre. The Kingdom included the cities of Beirut, Tyre, Tripoli and Antioch. The Mamluks under Sultan Baibars took all of the cities of the Kingdom of Jerusalem one by one until, in 1291, Acre, the last stronghold, was taken by the Sultan Khalil. The Kingdom of Jerusalem ceased to exist. The Rulers of the Kingdom of Jerusalem Between 1099 and 1291 the Kingdom of Jerusalem was ruled by many Europeans. The Kings and Queens who ruled the Kingdom of Jerusalem often appointed regents for the role. The names of the rulers of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were as follows: Godfrey of Bouillon - Protector of the Holy Sepulchre (1099 -1100) Baldwin I (1100 - 1118) Baldwin II (1118 - 1131) Melisende and Fulk (1131 - 1153) Baldwin III (1143 - 1162) Amalric I (1162 - 1174) Baldwin IV (1174 - 1185) Baldwin V (1185 - 1186) Sibylla and Guy of Lusignan (1186 - 1187) Isabella I (1192 - 1205) Maria of Montferrat (1205 - 1212) John of Brienne (1210 - 1212) Yolande (Isabella II) and Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor (1212 - 1228) Conrad of Hohenstaufen, Conrad II (1228 - 1254) Conrad III of Jerusalem (1254 - 1268) Hugh I (1268 - 1284) Charles of Anjou (1277 - 1285) John II (1284 - 1285) Henry II (1285 - 1291) Many European rulers claimed to be the rightful heirs to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, however none of these, have ever actually ruled over any part of the Kingdom. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/kingdom-of-jerusalem.htm Effects of the Crusades The Crusades kept all Europe in a tumult for two centuries, and directly and indirectly cost Christendom several millions of lives (from 2,000,000 to 6,000,000 according to different estimates), besides incalculable expenditures in treasure and suffering. They were, moreover, attended by all the disorder, license, and crime with which war is always accompanied. On the other hand, the Holy Wars were productive indirectly of so much and lasting good that they form a most important factor in the history of the progress of civilization. The effects of the crusades influenced: The role, wealth and power of the Catholic Church Political effects Effects of the Crusades on Commerce Effects of the Crusades on Feudalism Social development Intellectual development Social Effects of the Crusades Effects of the Crusades - Intellectual Development Effects of the Crusades - Material Development Effects of the Crusades - Voyages of Discovery Effects of the Crusades on the Catholic Church The Crusades contributed to increase the wealth of the Church and the power of the Papacy. Thus the prominent part which the Popes took in the enterprises naturally fostered their authority and influence, by placing in their hands, the armies and resources of Christendom, and accustoming the people to look to them as guides and leaders. As to the wealth of the churches and monasteries, this was augmented enormously by the sale to them, often for a mere fraction of their actual value, of the estates of those preparing for the expeditions, or by the out and out gift of the lands of such in return for prayers and pious benedictions. Thousands of the crusaders, returning broken in spirits and in health, sought an asylum in cloistral retreats, and endowed the establishments that they entered with all their worldly goods Besides all this, the stream of the ordinary gifts of piety was swollen by the extraordinary fervor of religious enthusiasm which characterized the period into enormous proportions. In all these ways, the power of the Papacy and the wealth of the Church were vastly augmented. Effects of the Crusades on Commerce One of the most important effects of the crusades was on commerce. They created a constant demand for the transportation of men and supplies, encouraged ship-building, and extended the market for eastern wares in Europe. The products of Damascus, Mosul, Alexandria, Cairo, and other great cities were carried across the Mediterranean to the Italian seaports, whence they found their way into all European lands. The elegance of the Orient, with its silks, tapestries, precious stones, perfumes, spices, pearls, and ivory, was so enchanting that an enthusiastic crusader called it "the vestibule of Paradise." Effects of the Crusades on Feudalism The crusades could not fail to affect in many ways the life of western Europe. For instance, they helped to undermine feudalism. Thousands of barons and knights mortgaged or sold their lands in order to raise money for a crusading expedition. Thousands more perished in Syria and their estates, through failure of heirs, reverted to the crown. Moreover, private warfare, which was rife during the Middle Ages, also tended to die out with the departure for the Holy Land of so many turbulent feudal lords. Their decline in both numbers and influence, and the corresponding growth of the royal authority, may best be traced in the changes that came about in France, the original home of the crusading movement. Political Effects of the Crusades As to the political effects of the Crusades, they helped to break down the power of the feudal aristocracy, and to give prominence to the kings and the people. Many of the nobles who set out on the expeditions never returned, and their estates, through failure of heirs, escheated to the Crown; while many more wasted their fortunes in meeting the expenses of their undertaking. At the same time, the cities also gained many political advantages at the expense of the crusading barons and princes. Ready money in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries was largely in the hands of the burgher class, and in return for the contributions and loans they made to their overlords, or suzerains, they received charters conferring special and valuable privileges. And the other political effects of the Crusades was that in checking the advance of the Turks the fall of Constantinople was postponed for three centuries or more. This gave the early Christian civilization of Germany time to acquire sufficient strength to roll back the returning tide of Mohammedan invasion when it broke upon Europe in the fifteenth century. Social Effects of the Crusades The Social effects of the Crusades upon the social life of the Western nations were marked and important. The Crusades afforded an opportunity for romantic adventure. The Crusades were therefore one of the principal fostering influences of Chivalry. Contact with the culture of the East provided a general refining influence. Effects of the Crusades - Intellectual Development The influence of the Crusades upon the intellectual development of Europe can hardly be overestimated. Above all, they liberalized the minds of the crusaders. The East at the time of the Middle Ages surpassed the West in civilization. The crusaders enjoyed the advantages which come from travel in strange lands and among unfamiliar peoples. They went out from their castles or villages to see great cities, marble palaces, superb dresses, and elegant manners; they returned with finer tastes, broader ideas, and wider sympathies. The crusades opened up a new world. Furthermore, the knowledge of the science and learning of the East gained by the crusaders through their expeditions, greatly stimulated the Latin intellect, and helped to awaken in Western Europe that mental activity which resulted finally in the great intellectual outburst known as the Revival of Learning and the period of the Renaissance. Effects of the Crusades - Material Development Among the effects of the Holy Wars upon the material development of Europe must be mentioned the spur they gave to commercial enterprise, especially to the trade and commerce of the Italian cities. During this period, Venice, Pisa, and Genoa acquired great wealth and reputation through the fostering of their trade by the needs of the crusaders, and the opening up of the East. The Mediterranean was whitened with the sails of their transport ships, which were constantly plying between the various ports of Europe and the towns of the Syrian coast. In addition to the effects of the crusades on material development various arts, manufactures, and inventions before unknown in Europe, were introduced from Asia. This enrichment of the civilization of the West with the "spoils of the East" can be seen in the artifacts displayed in modern European museums. Effects of the Crusades - Voyages of Discovery Finally, the incentive given to geographical discovery led various travelers, such as the celebrated Italian, Marco Polo, and the scarcely less noted Englishman, Sir John Mandeville, to explore the most remote countries of Asia. Even that spirit of maritime enterprise and adventure which rendered illustrious the fifteenth century, inspiring the voyages of Columbus, Vasco de Gama, and Magellan, may be traced back to that lively interest in geographical matters awakened by the expeditions of the crusaders. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/effects-of-crusades.htm Crusades Timeline The following Crusades Timeline provide the basic dates and key events of all the crusades in the two hundred years when Europe and Asia were engaged in almost constant warfare. Crusades Timeline The Crusades Timeline Crusade Dates of Crusade First Crusade 1096 - 1099 Second Crusade 1144 -1155 Third Crusade 1187 -1192 Fourth Crusade 1202 -1204 The Children's Crusade 1212 Fifth Crusade 1217 - 1221 Sixth Crusade 1228 - 1229 Seventh Crusade 1248 - 1254 Eighth Crusade 1270 Ninth Crusade 1271 - 1272 Crusades Timeline of Events The People's Crusade - Freeing the Holy Lands. 1st Crusade led by Count Raymond IV of Toulouse and proclaimed by many wandering preachers, notably Peter the Hermit Crusaders prepared to attack Damascus. 2nd crusade led by Holy Roman Emperor Conrad III and by King Louis VII of France 3rd Crusade led by Richard the Lionheart of England, Philip II of France, and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I. Richard I made a truce with Saladin 4th Crusade led by Fulk of Neuil French/Flemish advanced on Constantinople The Children's Crusade led by a French peasant boy, Stephen of Cloyes The 5th Crusade led by King Andrew II of Hungary, Duke Leopold VI of Austria, John of Brienne The 6th Crusade led by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II The 7th Crusade led by Louis IX of France The 8th Crusade led by Louis IX The 9th Crusade led by Prince Edward (later Edward I of England) http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/crusades-timeline.htm Crusaders Who were the Crusaders? What age were they? Did women travel to the crusades? And what prompted people to undertake the incredibly arduous journey from Europe to the Middle East? The Numbers of Crusaders What could possess tens of thousands of people to travel to a country over 1000 miles away when most people in the Middle Ages never left their villages? The first crusade was called the 'People's Crusade'. Men, women and children were so motivated by the preaching’s of men like Peter the Hermit and Walter the Penniless that they left their homes and followed the call to the crusades. The crusaders, consisting of ordinary people, who followed Peter the Hermit eventually numbered over 15,000. Other massive numbers of crusaders followed men like Walter the Penniless and the numbers increased to 80,000. The Knights and armies did not accompany these people - the military expeditions took far longer to organize. The estimated forces of the First Crusade numbered 4,500 cavalry and 30,000 foot soldiers. The Crusaders of the First Crusade traveled overland to Jerusalem. The Route of French Crusaders The route of the French Crusaders of the First Crusade passed France, Italy and Greece on to Palestine through the following cities: Paris Lyon Genoa Rome Brandusium Constantinople Edessa Antioch Jerusalem Mustering the Crusaders Western Europe rang with the cry, "He who will not take up his cross and follow me, is not worthy of me." The contagion of enthusiasm seized all classes; for while the religious feelings of the age had been specially appealed to, all the various sentiments of ambition, chivalry, love of license, had also been skillfully enlisted on the side of the undertaking. Promises made to Crusaders The council of Clermont had declared Europe to be in a state of peace. The council took action to ensure that peace in Europe was maintained: The council pronounced a formal ecclesiastical ban, curse, or excommunication against any one who should invade the possessions of a prince engaged in the holy war By further edicts of the assembly: all crusaders, were instantly absolved from all his sins, of whatever nature any debtor was released from meeting his obligations whilst he was a soldier of the Cross and the interest on any debts were to cease Under such inducements princes and nobles, bishops and priests, monks and anchorites, saints and sinners, rich and poor, hastened to enroll themselves beneath the consecrated banner. Every one was eager to become crusaders The Crusaders of the Upper Classes The crusades were not simply an expression of the simple faith of the Middle Ages. Something more than religious enthusiasm sent an unending procession of crusaders along the highways of Europe and over the trackless wastes of Asia Minor to Jerusalem. The crusades, in fact, appealed strongly to the warlike instincts of the feudal nobles. They saw in an expedition against the East an unequalled opportunity for acquiring fame, riches, lands, and power. The Normans were especially stirred by the prospect of adventure and plunder which the crusading movement opened up. By the end of the eleventh century they had established themselves in southern Italy and Sicily, from which they now looked across the Mediterranean for further lands to conquer. The Crusaders of the Lower Classes The crusades also attracted the lower classes. So great was the misery of the common people in medieval Europe that for them it seemed not a hardship, but rather a relief, to leave their homes in order to better themselves abroad. Famine and pestilence, poverty and oppression, drove them to emigrate hopefully to the golden East. The Privileges of the Crusaders The Church, in order to foster the crusades, therefore promised both religious and secular benefits to those who took part in them. A warrior of the Cross was to enjoy forgiveness of all his past sins. If he died fighting for the faith, he was assured of an immediate entrance to the joys of Paradise. The Church also freed him from paying interest on his debts and threatened with excommunication anyone who molested his wife, his children, or his property. The Crusaders of the People's Crusade Before the regular armies of the crusaders were ready to move, those who had gathered about Peter the Hermit, becoming impatient of delay, urged him to place himself at their head and lead them at once to the Holy Land - the People's Crusade. Dividing command of the mixed multitudes with a poor knight, called Walter the Penniless, and followed by a throng of about 80,000 persons, among whom were many women and children, the Hermit set out for Constantinople by the overland route through Germany and Hungary. Thousands of the crusaders fell in battle with the natives of the countries through which they marched, and thousands more perished miserably of hunger and exposure. Those that crossed the Bosporus were surprised by the Turks, and almost all were slaughtered. http://www.middle-ages.org.uk/crusaders.htm