The Human Development Index and beyond

advertisement

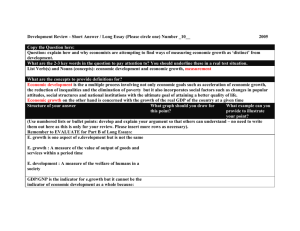

Statistics, Development and Human Rights Session I-PL 6/7 The Human Development Index and Beyond: Which Are the Prerequisites for a Consistent Design of Development Indicators - Should There Be a Human Development Index? Jacob RYTEN Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights The Human Development Index and Beyond: Which Are the Prerequisites for a Consistent Design of Development Indicators - Should There Be a Human Development Index? Jacob RYTEN "Southleigh" Cirencester, GL7 1TX, United Kingdom T. + 44 1285 657 606 F. + 44 1285 658 889 Rytenjacob@email.msn.com ABSTRACT The Human Developmet Index and Beyond: Which Are the Prerequisites for a Consistent Design of Development Indicators – Should There Be a Human Development Index? In this paper, the question is asked under which conditions should an official statistical agency engage in representing complex social changes by means of a single number. There are examples of successful single numbers such as the GDP. The circumstances for them to be useful and credible are examined and found not to exist in the case of the Human Development Index (HDI). The current method of calculating the HDI comes in for criticism because it does not take into account a measure of distribution even though social development can be stunted in the absence of a distribution regarded as fair and equitable by all. The indicators derived from the Health and Education sectors also come in for criticism because they lack a common structure. One such structure is proposed as a starting point for future research. The paper’s conclusions are that while the strength of a single number as a communication device is recognized, at this stage Human Development should be measured by a set of at least half a dozen numbers. In any event and for the time being, official statisticians should abstain from publishing a HDI and preferably ought to leave the publication of related numbers in the hands of either their research arm or with research institutions. RESUME L’Indice du Développement Humain et au-delà : Quels sont les pré-requis pour une conception cohérente des indicateurs du développement - Devrait-il y avoir un Indice de Développement Humain? Dans cette présentation, la question est de savoir dans quelles conditions une agence officielle des statistiques pourrait s’engager dans la représentation de changements sociaux complexes moyennant de simples chiffres. Il existe des exemples de simples chiffres couronnés de succès tels que le GDP. Les circonstances les rendant utiles et crédibles ont été examinées et il se trouve qu’elles ne sont pas présentes dans le cas de l’Index sur le Développement Humain (HDI). La méthode habituelle de calcul du HDI est l’objet de critiques car elle ne tient pas compte d’une mesure de distribution même si le développement social peut être retardé en l’absence d’une distribution considérée comme loyale et équitable par tous. Les indicateurs dérivés du secteur de la Santé et de l’Education sont aussi l’objet de critiques car une structure commune leur fait défaut. Une telle structure est proposée comme point de départ de la recherche future. Les conclusions de 2 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights cette présentation sont les suivantes : quoique la force d’un simple chiffre en tant qu’outil de communication soit reconnue, à ce stade le développement humain devrait être mesuré par un ensemble d’au moins une demi-douzaine de chiffres. A l’occasion de tout événement et jusqu’à nouvel ordre, les statisticiens officiels devraient s’abstenir de publier un HDI et de préférence laisser la publication de tels chiffres aux mains soit de leur section de recherche, soit des institutions de recherche. 1. Background At first I wanted to limit my efforts to debunking the idea of a Human Development Index (HDI). Official statisticians ought to resist the lure of single numbers designed to represent complex social changes until such time as those numbers are solidly backed by theory and by operational definitions of the magnitudes they purport to represent. There are several single numbers that have been extraordinarily successful in conveying environmental information to the general public, danger signals to policy makers, and an empirical basis for academics to test theoretical hypotheses. But not all complex realities lend themselves to representation by a single number nor does it follow when the matter is still the subject of active research that official statistical agencies ought to lend their stamp of legitimacy by making the single number public. The experience of the international statistical community with the International Comparison Project 1 convinced me that the criteria that allow us to adopt certain numbers as official must be made explicit. But if a particular number exists, has even acquired some legitimacy by virtue of being around for some time and yet must be debunked, it is the burden of the debunker to suggest an alternative. At this stage I have not yet come to the formulation of such an alternative. I do have arguments to suggest that in the absence of certain initial conditions, one should sacrifice the simplicity of a single number for the sake of a more robust and more nuanced description, in this case of “human development”. While I have no operational definitions of what it is that we should be measuring nor of a proposal to aggregate the various measurements, I do have an outline of the direction in which I would like to see research go, the underlying assumptions to justify it, and the steps that should be taken if the proposal below is considered to hold promise. My paper attempts to discuss – if not to answer - the following questions. Firstly, when is it legitimate to compile a single figure to represent a complex social (or economic, or environmental) reality? Secondly, what are the circumstances that make it acceptable for an official statistical agency to publish a particular statistic? Thirdly, is the Human Development Index a construct with interesting properties? Fourthly and lastly, are there more useful and more interesting alternatives to the current HDI? 2. The first question : When is it legitimate to compile a single figure to represent a complex social (or economic, or environmental) reality? There are well known examples of single figures used currently to represent complex changes. To start with the best known of all – the GDP - we have all come across statements of the following form and content: “…in the two last quarters, real GDP growth has slowed down considerably making it virtually impossible to reach the 2 per cent per annum forecast by the Ministry of Finance …” In this hypothetical example, no one would question the adequacy of the concept of GDP to provide a warning to the authorities that for reasons to be looked into, the rhythm of economic J. Ryten: “The International Comparison Project” An Evaluation Report, 29 the Session of the United Nations Statistical Commission. New York 1998. Ian Castles: Review of the Eurostat-OECD PPP Programme, OECD Paris 1997 3 1 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights activity was insufficient to attain an official government expectation. Underlying the concept of GDP are many complex conventions, accepted internationally, and abided by all serious practitioners. For example, there is the convention on how to separate capital from current expenditure; where to draw the production boundary; how to separate domestic from foreign transactions; how to divide changes in values measured in nominal monetary terms into the components caused by pure price variations and those accounting for all other causes; how to allow for the effect of seasons –climatic or institutional – on the quarter to quarter variation of GDP values; how to demarcate private from public transactions; and so on. Beyond agreement on definitional conventions there is an acceptance that national economies change slowly and therefore the figures that represent them are strongly auto correlated. What happens in one quarter is strongly conditioned by what happened in the previous quarter and in turn is a strong conditioner of what is to happen in the next. Given a particular value for one quarter – so goes the assumption - it is highly improbable for subsequent values to be very much different from what went on in the immediate past. These agreements did not always exist. There was a time when the GDP figure was viewed much as certain categories of experimental figures - the results of the Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) comparisons for example - are viewed today. In the early fifties there was a debate whether the GDP as an aggregate was interesting and suitable as a basis for action by Ministries of Finance; there was a question about the legitimacy of deflation and whether it led to meaningful results; there were doubts about the suitability of calculating GDP at quarterly intervals and whether the required degree of imputation was not such as to invalidate the resulting rates of change; and finally there was concern that seasonal adjustment distorted figures unjustifiably and that possibly the data should be left in their original condition. Even today there is no universal consensus over some of these questions. For example, there are statistical agencies (NSO’s) that claim that their role is to calculate the best possible basic statistics. They argue that transformations based on arguable assumptions such as seasonal adjustment and imputations based on deductive inferences rather than on empirical observation are best left to research departments and to academic institutions. The debate over whether a single quarterly GDP figure provided useful and reliable information lasted more than ten years. And whether it is the role of official statistical agencies to compile it is still a moot question in many parts of the world. Today the centre of discussion has shifted. In fact it has shifted to get closer to matters such as those that underlie the construction of a Human Development Index. The issues faced are whether the standards for GDP compilation and their definition of the production boundary are socially acceptable in the light of current public concerns. The fact that the GDP number excludes unpaid work conducted within the household is questioned by many quarters; that the GDP does not discriminate among agents and cannot answer how much of current production (and current income) is imputable to female participation and how much to the rest is reckoned to be a shortcoming by many critics. Moreover, to add to the current criticism, the income and expenditure accounts do not take into account the impact of production on natural resources – the rate at which the latter are being contaminated and depleted. In spite of these questions – and some of them deserve serious consideration – there is no serious doubt either among the user constituencies or among the official producers of GDP accounts that the number itself is necessary, whatever scope there may exist for its future improvement. Many policies are predicated on the timely publication of the GDP accounts and it is difficult to imagine how the public sector would organize its fiscal and financial activities if no GDP and related figures were made available. What are then the properties that a single high impact synthetic number should have, irrespective of who publishes it? 4 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights Properties of a high profile single number The following is not an exhaustive list but rather an enumeration of the key attributes of a high profile single number: • • • • • it must be communicable2 in the sense that if questioned, a short and simple explanation can be given of what the number pretends to measure and the elements that are required in order to compile it with the conviction that such an explanation will be accepted and understood by the majority of potential users; it must be replicable (more or less) in the sense that an interested user with access to sufficient resources, the same basic data, and armed with the same book of definitions and procedures will reach roughly the same results; it must be related to theory in the sense that if someone asked for the conceptual basis of the figure, an answer could be given in terms of the interrelationship of the components and in the particular instance of a HDI, where and how those components fit in a theory of social and economic development; it must be related to possible action in the sense that if the estimated figure behaves in a particular way, one can think of decisions that can and will be taken and policies that will or will not be adopted as a result; and it must be credible where credibility is associated with the authority and legitimacy of the compilers, the expected use of the figure in the framing of policies, and the perception that its estimation is based on objective methods rather than on partisan views. The attributes mentioned above are the most basic. In addition, the following technical characteristics are essential requirements: • • • the components of a synthetic number must be independent of each other. A sound construction of the synthetic number implies that subject to constant quality, the number of components must be minimized (efficiency). Sound construction also implies that subject to the input being held constant the information yielded by the number must be maximized (effectiveness); the attributes must share a common metric or in the absence of a common metric must be standardized (for example, expressed in units of standard deviation from a natural origin); the manner in which the attributes are aggregated – the functional form and the weights – must be the result of a selection from an easily understandable set or else chosen so as to be robust. It must be possible to claim that there are no policy applications in sight that would be disadvantaged depending on the choice of the aggregation function and its weights. 3. Second question: What are the circumstances that prompt an official statistical agency to publish or refrain from publishing a particular statistic? In the past serious arguments have been put forward that would have statistical agencies give up on the compilation of the CPI. The alternative was that they should publish every month or every week a list of prices and the exact specifications of the goods and services to which those prices corresponded. They would also make available the latest pattern of consumer expenditure as well as 2 The following quote is reproduced from Ian Castles: Comments on the UNDP response to the Castles Critique of HDR 1999 “… Amartya Sen has explained that he came to accept Mahbub ul Haq’s view that the HDI was valuable ‘as an instrument of public communication’, in order to ‘[get] the ear of the world through the high publicity associated with [its] transparent simplicity … ‘ (‘Mahbub ul Haq: The courage and creativity of his ideas’, speech at the Memorial Meeting for Mahbub ul Haq, 15 October 1998). 5 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights software, which would make it possible for serious users to calculate their own index choosing the functional form that best suited their needs. This way the statistical agency would do what it knew best – to measure an operationally defined magnitude under controlled conditions; it would stay away from opting for one or another of several possible aggregation functions, all of which are controversial; and would allow users a better understanding of the concept underlying a CPI while giving them freedom of choice of how to combine many numbers into one, if they so wished. The tenor of this proposal is the logical consequence of the injunctions to stay away from controversial assumptions and to maintain objectivity throughout. But tradition, political realities, general acceptance and expectations, all combine to suggest that this view is much too extreme and that it is in line with the mission of an NSO to compile the CPI. Even so, what are the conditions that demand that a line be drawn? There is a category of aggregates that most if not all statistical agencies would refuse to compile. What are the grounds for refusal? Or is there virtue in remaining ambiguous because no one is sure of how to describe those grounds? Official statistical agencies have not developed or been provided with an international agreed code of “publishability”. There are codes of quality and texts proffering advice on suitability and relevance. For example, on the IMF website, the references to data quality in the papers and reports quoted - address “fitness for use”3 in terms of timeliness, precision, error, cost, and other dimensions normally associated with quality. But those standard quality attributes do not answer the underlying question of whether it is appropriate for a statistical agency to lend its legitimacy and moral endorsement to a particular number nor do they examine the theoretical (as derived from social science rather than from statistics) attributes that number should have. In other words, they do not question what statistics a statistical agency should regard as fit to publish. It follows that ultimately, the decision whether or not to publish is very much in the hands of the head of an NSO and his immediate advisers. Suppose the example is “human development” and the management of an NSO identify a user and a use. The user argues justifiably that the GDP is much too limited a variable. High GDP per capita is compatible with socially atrophied situations – situations where there is high illiteracy and health standards are poor. Accordingly the GDP per capita is rated to be an incomplete measure if not downright misleading for certain policy purposes. The user is prepared to fund the compilation of an alternative so long as the alternative includes explicitly those social dimensions about which the GDP has nothing to say and which we shall assume are not strongly related to GDP per capita. The explicit purpose of the index is to provide an objective measure of “development” to help with the allocation of funds presumably to combat social deprivation in the form of low life expectancy, high illiteracy, low rates of access to social services etc. The alternative to having the official statistical agency compile such a number is to have it compiled and published by a private research institution, which of course is in no position to stamp the result with the trademark of the statistical agency. Suppose that there is an international dimension to this initiative and that an international consensus has been reached on the name, components, and aggregation form for the new synthetic measure. What is the right course of action for the official statistical agency? Properties of a number fit to publish (as opposed to a number “fit to use”) The following may constitute criteria to decide whether or not to publish: • 3 Relevance. If a number is to be compiled it must have a final user and a final use both of which the authorities in charge of an official statistical agency can identify and rank as of sufficient priority to justify the effort; G. Brackstone: Managing Data Quality in a Statistical Agency, Survey Methodology, December 1999, Ottawa. 6 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights • • Robustness. Even though a synthetic number may be well compiled in the sense that all its components are correctly estimated, the aggregation function may be so sensitive to small changes in weights or in the functional form that its usefulness as an effective guide to decision taking is questionable. Moreover, if a number is unstable over time its credibility. For example, suppose that a group of countries are ranked using an index that makes inter-country comparisons possible. Suppose two rankings take place at times t and t+k. Suppose that the rank correlation between the two rankings is no better than if the two had no relationship. What credibility would we attach to the procedure if we knew that the ranking variable changed slowly irrespective of the country to which it applied? The point is that we expect some constancy of characteristics over time and movements that are too rapid incite our suspiciousness. This gets aggravated if there is no accepted body of theory capable of explaining the shifts. Adequacy. For an ongoing statistic to be useful it must keep on answering the right question. One way to explain this property is by example. Suppose there is the question of adopting a CPI to measure inflation in a traditional society. The decision is to opt for a Laspeyres price index on the grounds that to inform the government (assuming that it wants to be informed) about whether there are any inflationary (or deflationary) pressures on the horizon, it is sufficient to measure the changes in expenditure on a fixed basket of goods and services. Now suppose the society surrenders to a rapidly changing technology and the consequent changes in expenditure pattern, and the speed at which the pattern is changing become the question of the day. Even though the CPI answers the earlier question well, the question it answers is no longer the right one. 4. Third question: Is the Human Development Index a construct that has interesting properties? The answer is probably “no”. But a few remarks to set the stage are in order. For a synthetic number such as the HDI to be interesting it must be sufficiently different from all others not to be redundant; it must be sensitive to change to provide signals while at the same time time-resistant so as not to signal in excess; and its changes must lead to questions that in turn provide a basis for insights. It is not specifically a number designed to settle questions of fact because such questions are usually settled by reference to a basic statistic. As an example: has the school enrolment gone up or down this year in relation to last? The answer is settled by looking up a time series of basic enrolment statistics. If the variations of a synthetic number are mostly caused by one of its components, it is the component that is worthy of attention and study. Take the example of the HDI as calculated in the Human Development Report. It consists of three components: GDP per capita corrected by purchasing power parities (PPP’s); life expectancy at birth; and a combination of literacy and gross enrolment rates. In other words, the goal of human development is to produce a citizen who is affluent, healthy and well educated. Now let us make the reasonable assumption that health and knowledge (or literacy or education however defined) are long-term functions of income and that their variation is explained by the lagged variation in GDP. It follows that the synthetic measure fails on account of redundancy. Moreover the interesting insights the HDI might give rise to are in fact derivable from those of the responsive component. Suppose alternatively that the three components are independent but respond to policy at very different speeds. Imagine that the two social components are slow moving partly because they are demography driven and partly because they presume very different lengths of what economists would call “roundaboutness”. If the period of observation is one year and some policy is instituted to act on all components naturally the driver of the synthetic index will be the most responsive. So 7 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights once again an index constructed on that basis fails the redundancy test. Suppose that all components of a synthetic index can move up or down but that in the case of one of them, a downward movement implies a catastrophic event (life expectancy?) whereas downward movements in the case of the others are subject to relatively quick recovery. In such a case we do not wish the synthetic index to obscure the movements of the components and would prefer to see on its own the component that records catastrophic events. In this example, the synthetic index obscures rather than sheds light on the matter under study. Suppose a synthetic index is designed in order to construct an international league table and imagine that all countries are ranked by their shortfall from some average or by the value of their HDI. And suppose that the probabilities of variation in components other than the GDP are as much a function of explicit policies as they are of the initial demographic composition of the country. It follows that for the same amount of effort, assuming that all else is constant, the outcome will be different depending on the demographic structure about which little if anything can be done and certainly not in the short run. These reasons should be sufficient to argue that an HDI – such as we know it - may not have properties that are analytically interesting. 5. Fourth Question: Index of Human development: are there more useful and interesting alternatives? The answer is probably yes. But first consider the following. Other than simplicity and communicability and other than a residual dissatisfaction with GDP or with a related measure such as consumption of goods and services per capita, are there reasons to attempt to compile a single indicator to represent the social and economic sides of human development? The answer is probably not in the sense that there is no theory other than the trite statement that the richer a society, the greater its production and consumption possibilities, the faster the increase it experiences in longevity, probability of surviving the first year of life, literacy, feeling at home with the achievements of modern technology, participation in community development, etc. Conversely, there is the argument that sustained growth requires a number of fundamentals such as high literacy rates, good health and health care etc. The point is that there is no tested theory to link the social, environmental and economic factors that are required for human development and therefore the synthetic index is no more than a statistical device to make possible the aggregation of selected indicators presumed to be relevant but with unknown inter-relationships. Other attributes Irrespective of which way the causality links go – they may go both ways but at different speeds - the list of ingredients that constitute the development index, leaves out for no explainable reason a number of important factors that one might imagine are also worthwhile considering. For example: • • • • • Uncertainty, especially uncertainty in the labour market but also uncertainty with respect of the value of fixed income; Predictability (the converse of uncertainty) through the absence of corruption, the sanctity of contract, the openness of government, and the fairness of public administration; Security (related as a distant cousin to the two above) from internal and external dangers; Upward mobility. To expect that one’s probability of economic and social success (however defined) not be conditioned by circumstances of birth, sex, ethnic origin, social class etc. Absence of excessive inequality. The situation where neither income nor wealth is disproportionately concentrated in the hands of the privileged few. 8 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights The list could be considerably longer. Moreover for each of these attributes one could devise one or more statistical indicators, all of them susceptible of being defined, measured, compiled, standardized, and used as ingredients to construct a synthetic index. The problem though would remain in our inability to define a criterion for aggregation because no theory exists that provides an underlying conceptual framework. Distribution, concentration, inequality In addition to the fact that a synthetic indicator such as the HDI is deficient in theoretical terms, its properties in a number of boundary cases are questionable. Consider that the current HDI is marked by the absence of a measure of distribution or concentration of income and wealth and imagine the following: • • • • • • • • There is a country called Kryptonia; Kryptonia has an index that combines one well known economic indicator (production, household consumption what have you) with several social indicators (derived from health and education); The economic indicator varies relatively fast but the social indicators vary slowly; Wealth and income are poorly distributed – according to a consensus view. Indicators of inequality – whatever they are – suggest that a small proportion of the population owns most wealth and accounts for most income. All the others live as serfs. The country’s wealth is derived from a unique resource in high demand – let us call it Kryptonite; The international prices of Kryptonite went up but since demand for the resource is highly inelastic so did incomes. There was no short term effect on internal income distribution; There is trickle through - as is implicitly assumed in human development indexes – but it is much slower than the increase in incomes and assets experienced by the privileged few; The HDI of Kryptonia goes up faster than the HDI of other countries particularly of those that are buyers of kryptonite rather than sellers. Is this a property that we want a HDI to have? And if not, how should we change it? 6. Ménage à trois, ménage à quatre: a proposal One possibility to modify the HDI while retaining the same components and supplying it with a structure that it sorely misses is to consider for each of them three analogous conditions: the ratio of actual to eligible entrants; the efficiency of transformation of inputs into outputs; and the ratio of actual to potential outputs. In the case of education the three conditions translate themselves into an average of enrolments; a ratio of graduates to entrants; and a ratio of graduates to the relevant portion of the population (after netting out duplication). To find exact measurable counterparts in the case of health is not that easy. In the case of the GDP derived indicators it is understood that they must be adjusted for Purchasing Power Parities. 9 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights Purchasing Power parities – a sideline At the same time as there is an effort to find suitable indicators for a comparative study of the conditions of human development, there is still some dithering about the use of Purchasing Power Parities in the adjustment of values expressed in nominal monetary terms. 4 The evidence that there is no alternative to this adjustment and that comparisons made on the basis of exchange rate terms are wildly misleading is overwhelming. 5 While there is genuine doubt about the management and the resources made available for the corresponding statistical programmes there should be no hesitation in ruling out the alternatives. In the discussion that follows it is understood that all GDP related indicators are PPP adjusted and researchers engaged in improving the statistics necessary to compare human development are encouraged to devote some of their rime and resources to a corresponding improvements in the quality of the purchasing power numbers. The following are the elements of my proposal for an alternative to the HDI. The proposal is addressed to national and international official statistical agencies. It includes a research programme for official statistical agencies interested in pursuing the matter. 1. Resist the temptation to publish a single number to measure “human development”, a single figure measuring the shortfall in “human development”, or any other variant that ends up by being a single figure; 2. Accept the idea that for a suitable description of human development to be given, more than one figure is necessary. Think in terms of a situation where you are asked to provide all the expenditure components of GDP but you are barred from adding them up because they lack a minimum of coherence; 3. Think in terms of a description that improves by adding modules as more research takes place into the various dimensions of human development and as operational definitions for each of those dimensions are proposed. As more is known about a certain feature of human development – access to public services or participation in political life or engagement in voluntary associations – a corresponding module is drawn up; 4. Refrain from the temptation of compiling international league tables even if there are solid international agreements that ensure that all modules are calculated in the same way and there is guaranteed inter country comparability. At this stage of our knowledge, league tables are silly and give rise to unjustified and invidious comparisons. 5. Provide all modules with a structure and try and make it the same even if in some cases – at least at first – the results look somewhat forced. Inevitably there will be gaps either because the indicator cannot be compiled or because the underlying concept cannot be found. Let those gaps constitute a programme of research nationally and internationally. 4 5 See United Nations Development Report 1999. New York 1999 See Castles and Ryten, op.cit 10 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights 6. Examine how sensitive the results are to different types of weighting in the first instance to be able to reject all attempts at forcing the premature creation of a single figure. 7. Make very sure that there is clarity in the minds of the public as to who calculates the basic indicators of human development and explain the inadequacy of an “ersatz” single figure for the spurious purposes of engaging in international comparisons. 8. For purposes of research, development, and publication use a framework along the lines of Table 1 below. Table 1 Framework for an alternative to HDI Modules Stages Economic growth Health Input Employed as proportion of total labour force Transformation Ratio of hours worked to total number of hours; labour productivity GDP per head Education Infantile mortality; rate of maternal mortality ? Life expectancy Output Distribution Gini coefficient of income distribution or equivalent “Healthfulness” coefficient Other Enrolments in first year of each stage of the formal education system ? Ratio of graduations to enrolments ? Successful graduates over total possible graduates ? Rate of functional ? literacy Notes to the proposal A great deal remains to be done within this framework. For example: is there a means of combining a measure of central tendency – GDP per capita or household consumption per capita – with a measure of distribution? Ands if so, what would the combined number mean? An arbitrary score? What is the most suitable measure of distribution? One possibility is to popularise the Gini coefficient. But it has known shortcomings. There are more sophisticated alternatives. Measures of entropy6 have interesting properties but can they be readily explained to politicians and to the public? And if they cannot, how is a combined figure to gain credibility? Whatever measure is adopted it is important to bear in mind that it must retain the property of communicability. Thus if a number is adopted but cannot be explained in as many words as say the CPI or the maternal mortality at birth, the chances are that it will not flourish. Even so a successful number must take into account distribution of income and wealth (or at least income). After all, human development 6 The Kullback-Liebler measure or the Theil coefficient of redundancy for example. 11 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000 Statistics, Development and Human Rights as commonly understood would be thwarted if most means of purchase remain in the hand of the very few. Nor is the first of the columns the only one that is open ended. What is the output of the health sector, awkwardly designated as “healthfulness” in the table? Somehow one would like to have a physical output measure similar in concept to caloric equivalent. For example, can healthfulness be measured in pain free days? And what is the health sector counterpart of years spent in school? Is there a counterpart to measure the society’s capacity to restore to health those afflicted by disease and pain? And subsequently to measure the ratio of those restored to those that could be restored if the capacity were fully utilized? Implications of the proposal The obvious implication is that instead of publishing a single figure – one index or one shortfall – each country would be characterized by at least a triplet and each component of the triplet might be a set of two figures. Accordingly: Table 2 What replaces the single figure “Achievement” Distribution Total goods and services X11 X21 Education Health X12 X22 X13 X23 7. Conclusions Before attempting to publish a sextuplet, a study must take place into the most effective means of aggregating the component indicators. It is not obvious how to combine a number on unemployment with a number on productivity and one number on the GDP even though the set is much more coherent than the grouping that constitutes the HDI. The recommendation in this paper is for a systematic structure that can be expanded over time to span other indicators of development on the basis of further research. Assuming that research is crowned with success, it will still be awkward to replace a single figure by a sextuplet and to have to analyze the evolution of six numbers so as to make them readily understandable to policy analysts. But ultimately, if the choice is to mislead with a single figure or to explain awkwardly with six, the latter should be professionally if not emotionally preferable. 12 Montreux, 4. – 8. 9. 2000