As our society becomes more technologically advanced, new

advertisement

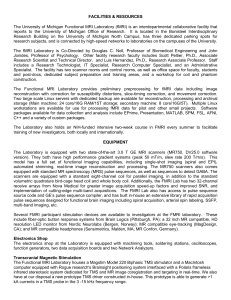

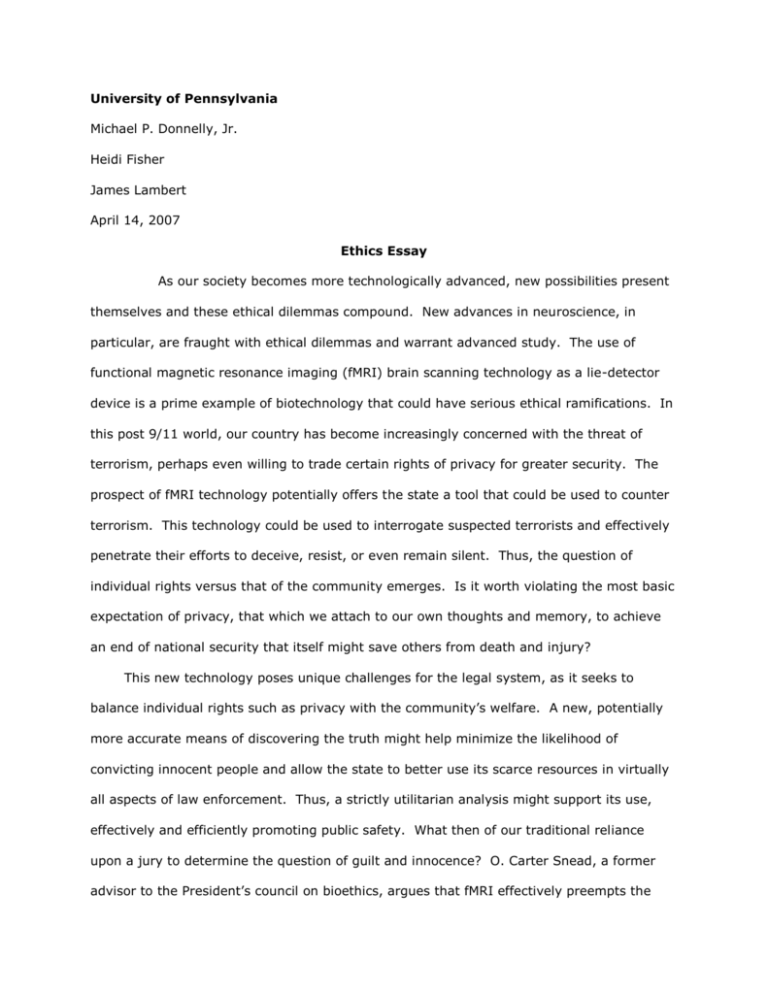

University of Pennsylvania Michael P. Donnelly, Jr. Heidi Fisher James Lambert April 14, 2007 Ethics Essay As our society becomes more technologically advanced, new possibilities present themselves and these ethical dilemmas compound. New advances in neuroscience, in particular, are fraught with ethical dilemmas and warrant advanced study. The use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) brain scanning technology as a lie-detector device is a prime example of biotechnology that could have serious ethical ramifications. In this post 9/11 world, our country has become increasingly concerned with the threat of terrorism, perhaps even willing to trade certain rights of privacy for greater security. The prospect of fMRI technology potentially offers the state a tool that could be used to counter terrorism. This technology could be used to interrogate suspected terrorists and effectively penetrate their efforts to deceive, resist, or even remain silent. Thus, the question of individual rights versus that of the community emerges. Is it worth violating the most basic expectation of privacy, that which we attach to our own thoughts and memory, to achieve an end of national security that itself might save others from death and injury? This new technology poses unique challenges for the legal system, as it seeks to balance individual rights such as privacy with the community’s welfare. A new, potentially more accurate means of discovering the truth might help minimize the likelihood of convicting innocent people and allow the state to better use its scarce resources in virtually all aspects of law enforcement. Thus, a strictly utilitarian analysis might support its use, effectively and efficiently promoting public safety. What then of our traditional reliance upon a jury to determine the question of guilt and innocence? O. Carter Snead, a former advisor to the President’s council on bioethics, argues that fMRI effectively preempts the role of the jury. Evidence, scientific and otherwise, is meant to help the jury make an informed decision, rather than make the decision for them. The use of this technology could eliminate the human aspect of the legal process, denying the defendant the right to be judged by a jury of his/her peers. Furthermore, the use of fMRI as a lie-detector would violate the right to escape self-incrimination granted by the Fifth Amendment if viewed as compulsory. The very existence and use in court of fMRI would render it compulsory, for there would be a built in bias against any suspect that chose not submit to it. If we have the right to avoid self-incrimination, do we not also have the right to our private thoughts and memories? Yet surely some are likely to maintain that such a tool is no more intrusive than a blood sample or fingerprint. Finding the truth deserves great priority, but the means must be just. What do we lose when the state penetrates our innermost thoughts, feelings, and memories? Our minds are particularly sacred to us, for our thoughts make up our very consciousness and define who we are. This intrusion, on the innocent as well as the guilty, should not be condoned in the pursuit of truth. If this technology is ever to be used by the government or in a legal system, it needs to be subjected to regulation that limits it application and recognize those rights and capacities that define our humanity. 2