1 What is the Phillips curve and its policy implication? Phillips Curve

advertisement

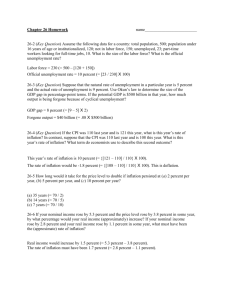

1 What is the Phillips curve and its policy implication? Phillips Curve shows the trade off relationship between the rate of inflation and unemployment rates. In other words, according to William Phillips’s empirical observation of the British economy of 1861 to 1957, there was a negative correlation between the rate of inflation and unemployment rate. In this Phillips curve, in order to achieve a lower unemployment or a higher level of national income, a policy-maker must pay the cost of a higher rate of inflation. How do you relate it to the Short-run Aggregate Supply curve? We also know that there is a negative correlation between unemployment rate and national income. Thus, we can infer that according to the Phillips curve there is a negative correlation between the rate of inflation and national income. That is ‘almost’ the same as the short-run aggregate supply curve (SAS) except that the SAS shows the trade-off between the level of price and national income while the Phillips curve implies the negative correlation between the rate of change in price level and national income. Just as we can mark the full employment national income or Yf in the SAS, we can mark down the corresponding natural rate of unemployment or the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment(NAIRU), which means that as long as the actual unemployment does not exceed this threshold there is no pressure on inflation. (Three Graphs 1, 2, and 3 for Illustration) Modification to the Expectation-augmented Phillips Curve Later studies showed that the trade-off between inflation and unemployment rates became fuzzy and doubted the validity of the Phillips curve. (Graph 4 from class to be inserted) Edmond Phelps won the Nobel Prize(2006) for adding a third variable of inflation expectations by the general public and rescuing the Phillips curve: There is not one Phillips curve, but are many Phillips curves which correspond to different rates of expected inflation. In other words, an expected rate of inflation is a shift variable for the Phillips curve. (Graph 5 to be inserted) In this ‘Expectations-augmented Phillips curves, at the natural rate of unemployment or NAIRU(do you recall what it stands for?), the expected rate of inflation, as the shift variable of a Phillips curve, is the same as the actual rate of inflation on the vertical axis. In other word, when the expected and actual rates of inflation are equal to each other, regardless of what the 2 numerical rates are, the national income is at the full employment level. The idea here is similar to the expectation-augmented aggregate supply curve or Lucas’s aggregate supply curve while the Expectations-augmented Phillips curves are shown in terms of the trade-off between ‘inflation rates’ and unemployment rates and the EAS or Lucas’s AS is described in terms of the negative relationship between ‘the Price Level’ and national income. Thus, we can have a vertical line above the NAIRU which passes through all Phillips curves of different expectedinflation rates (and the corresponding same actual rates of inflation respectively). Some may call this ‘the Long-run Phillips curve’ in contrast to Expectations-augmented Phillips curves. (Graphs 6, 7, and 8 to be inserted) Application of Expectation-Augmented Phillips Curves The application of EAPC is similar to that of EAS. When government accelerates money creation and thus the rate of inflation goes up, the unemployment rate may or may not come down depending on the inflation expectation of the general public: When the rate of inflation goes up and if the general public’s expected inflation does not change, the unemployment rate will fall. However, it is for only short-run until the general public figure out what is happening to inflation rates. Eventually, as they revise their expectations of inflation rates, the Phillips curve shifts up. The unemployment will come back to the NAIRU. (Graph 9 to be inserted) When the rate of inflation goes up and if the general public’s expected inflation change in line with it, the unemployment rate will not change. (Graph 10 to be inserted) We can put this change in a reverse gear: When government lowers the rate of inflation, the national income may or may not fall. If the people revise their inflation expectation down in line with the government policy, then there will be no changes in national income. However, if the people hold onto their current inflation expectation, which is higher than the rate of inflation to be realized, recession will take place with a higher rate of unemployment and a lower level of national income at least in the short-run. 3 When government lowers the rate of money creation and thus the rate of inflation, it may lead to ‘painless’ only when the general public revise their inflation expectation in line with the government policy. This is a successful ‘Disinflation Policy’, which means a lower inflation without a recession and thus an enhanced efficiency of resource allocation for the economy. In the Short- and Long-run, and the New Keynesian Histeresis. According to the above theory, in the long-run, as people figure out the reality and revise their expectations in line with reality, there is no trade-off between rates of inflation and rate of unemployment. In the long-run, economy moves along the Long-Run Phillips Curve. However, some new Keynesians have come up with a different idea from their empirical observation of some European countries of the 1980s. Suppose that an economy is initially at the full employment level, but with a high rate of inflation. Suppose that the government decides to have a disinflation policy. When the rate of inflation comes down and if initially people do not revise their expected inflation in line with the actual rate of inflation, the economy should first experience a recession. And then, eventually in the long-run as people revise their expectations, the economy should go back to the full employment level of national income or the NAIRU. However, if the economy has a ‘memory’ and is ‘path-dependent’, it may not go all the way back to the full employment level. This would be particularly the case if the recession has lasted for a while. This phenomenon is called ‘histeresis’: a supposed short-run increase of unemployment rates becomes permanently embedded in the economy as an additional part of NAIRU. Thus after recession as a result of disinflation, a new NAIRU is now higher than the previous NAIRU. In this case, the Long-Run Phillips Curve is not vertical but slanted. In this case, it will be very difficult to lower the rate of unemployment through a macroeconomic policy. The government may have to break up the hard core part of unemployment, that is, the NAIRU, through labor market policies. (Graph 11 to be inserted).