Romantic Movement (1785-1830)

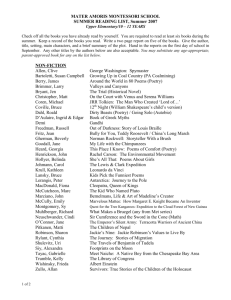

advertisement