2267. House of Lords Chapter 15 Dec 2008

1

Chapter 16a

The old Commonwealth: (a) Australia and New Zealand

The Hon Michael Kirby

*

Two nations overwhelmingly populated by sheep

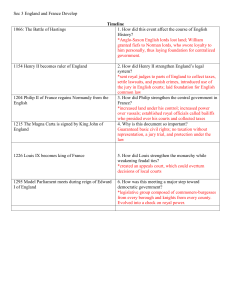

For a judicial body that is thousands of miles away, in a part of the world where the economic, social, cultural, and political circumstances are quite distinct from those prevailing in the southern hemisphere, the influence of the House of Lords on Australian and New

Zealand courts has been extraordinary. Especially so because, from colonial times, the House has never been part of the formal judicial hierarchy. This chapter will focus on the influence of the House of Lords since the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901 and the grant of Dominion status to New Zealand in 1907.

For a large part of the 20th century a self-imposed tradition of largely unquestioning adherence to House of Lords decisions existed in both Australia and New Zealand. This practice was so strong that, in Australia, the Lords ‘had sometimes been mistaken for a part of the Australian doctrine of precedent’.

1

Similarly, in New Zealand, English decisions were followed ‘almost as a matter of course’.

2 Lionel Murphy, one time Australian Attorney-

General and High Court Justice, regarded the deference paid to English precedents as an

*

Justice of the High Court of Australia. The author acknowledges the assistance of Ms Anna

Gordon, Research Officer in the Library of the High Court of Australia, and members of the

Faculty of Law, University of Otago in the preparation of this chapter.

1

AR Blackshield, ‘The High Court: Change and Decay’ (1980) 5 Leg Serv Bull 107, 107.

2

BJ Cameron, ‘Law Reform in New Zealand’ (1956) 32 NZLJ 72, 74.

2 attitude ‘eminently suitable for a nation overwhelmingly populated by sheep’ 3 —a comment specially apt for the two Southern outposts of the British Empire. Overall, this obedience was not altogether surprising. And, most of the time, it was substantially beneficial.

The source of influence of the House of Lords

When Australia and New Zealand were colonised by Britain the colonists inherited so much of English case law and statute law as was applicable to ‘their own situation and the condition of the infant colony’.

4

English law did not simply provide a foundation for Australian and

New Zealand law, as ‘the initial reception flowed without much distinction into the assumptions of precedent’.

5 In large part, English law was viewed as part of the precious birthright of the settlers.

The generally binding character of House of Lords decisions was affirmed by the Privy

Council, which had undoubted jurisdiction as the final court for the antipodean colonies. In

Robins v National Trust Company , Viscount Dunedin stated that the House of Lords ‘is the

3 LK Murphy, ‘The Responsibility of Judges’, Opening Address for the First National

Conference of Labor Lawyers, 29 June 1979, in G Evans (ed), Law, Politics and the Labor

Movement (Melbourne: Legal Service Bulletin, 1980) 5.

4

There was statutory recognition of this principle in s 24 of the Australian Courts Act 1828

(Imp) (9 Geo IV c 83). In New Zealand, this principle was reflected in the English Laws Act

1858 (Imp), which likewise adopted the laws of England.

5

PE von Nessen, ‘The Use of American Precedents by the High Court of Australia, 1901–

1987’ (1992) 14 Adelaide L Rev

181, 182.

3 supreme tribunal to settle English law, and that being settled, the Colonial Court, which is bound by English law, is bound to follow it’.

6

A primary reason for treating House of Lords decisions as effectively binding was a recognition of the fact that the membership of the Privy Council substantially overlapped with participation in the judicial work of the House of Lords. This made it sensible and prudent for judges in Australia and New Zealand to write their judicial reasons with ‘one eye to the prevailing English case law on the subject’.

7

So long as the right of appeal to the Privy

Council remained, the policy of following House of Lords decisions was considered ‘a practical necessity’.

8

In the 19th century and throughout much of the 20th century great weight was also placed on maintaining uniformity within the English common law or ‘ the Common Law’ as it was usually described. Indeed, as late as 1948, Sir Owen Dixon, later Chief Justice of Australia, considered that ‘[d]iversity in the development of the common law . . . seems to me to be an evil’.

9

6

[1927] AC 515, 519 (PC).

7 WMC Gummow, ‘The High Court of Australia and the House of Lords 1903–2003’ in G

Doeker Mach and KA Ziegert (eds), Law, Legal Culture and Politics in the Twenty First

Century (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2004) 44.

8

P Brett, ‘High Court—Conflict with Decisions of Court of Appeal’ (1955) 29 ALJ 121, 122; see also Cameron (n 2) 74; A-G for Hong Kong v Reid [1992] 2 NZLR 385, 392; Kapi v MOT

(1991) 8 CRNZ 49, 55; A Mason, ‘Future Directions in Australian Law’ (1987) 13 Monash L

Rev 149, 150.

9

Wright v Wright (1948) 77 CLR 191, 210.

4

Australia

A wise general rule of practice

The binding effect of the decisions of the House of Lords upon Australian courts was emphatically stated in 1943 in Piro v W Foster & Co Ltd .

10

The High Court of Australia upheld the decision of a trial judge in South Australia to follow more recent House of Lords decisions regarding the general principles applicable to an action for damages,

11

instead of an earlier, contrary decision of the High Court.

12

Whilst acknowledging that House of Lords decisions were not ‘technically’ binding, Chief Justice Latham declared that: 13

. . . it should now be formally decided that it will be a wise general rule of practice that in cases of clear conflict between a decision of the House of Lords and of the High

Court, this court, and other courts in Australia, should follow a decision of the House of Lords upon matters of general legal principle.

Justice Williams was the strongest supporter of the authority of the House of Lords decisions, stating that ‘[i]t is the invariable practice for the Australian courts, including this court, to

10

(1943) 68 CLR 313.

11

Caswell v Powell Duffryn Associated Collieries Ltd [1940] AC 152 and Lewis v Denye

[1940] AC 921.

12 Bourke v Butterfield and Lewis (1926) 38 CLR 354.

13

(1943) 68 CLR 313, 320. See also 325–6 (Rich J), 326–7 (Starke J), 336 (McTiernan J), and 341 (Williams J).

5 follow a decision of the House of Lords as of course, without attempting to examine its correctness, although the decision is not technically binding upon them . . .’

14

Professor Zelman Cowen, who was later to become Governor-General of Australia, commented that this decision ‘formally [wrote] the House of Lords into the hierarchy of tribunals whose decisions bind Australian Courts’.

15

The declaration of judicial independence

In 1963 the decision of the High Court of Australia in Parker v The Queen

16 heralded a change of attitude towards English precedent in Australian courts. The High Court declined to follow the decision of the House of Lords in DPP v Smith ,

17

which had established an objective test of intent for murder.

On the issue of precedential respect, with the rest of the

Court concurring, Chief Justice Dixon stated:

18

Hitherto I have thought that we ought to follow decisions of the House of Lords, at the expense of our own opinions and cases decided here, but having carefully studied

Director of Public Prosecutions v Smith [1961] AC 290 I think that we cannot adhere to that view or policy. There are propositions laid down in the judgment which I

14

ibid 341.

15

Z Cowen, ‘The Binding Effect of English Decisions Upon Australian Courts’ (1944) 60

LQR 378, 381.

16 (1963) 111 CLR 610.

17

[1961] AC 290.

18

(1963) 111 CLR 610, 632–3.

6 believe to be misconceived and wrong. They are fundamental and they are propositions which I could never bring myself to accept . . . I wish there to be no misunderstanding on the subject. I shall not depart from the law on the matter as we have long since laid it down in this Court and I think that

Smith’s Case

[1961] AC 290 should not be used in Australia as authority at all.

In time, the Privy Council would also follow the approach of the High Court, returning to more orthodox doctrine from which the Australian court would not be budged.

19

Confirmation of the new approach

The general approach taken in Parker v The Queen was confirmed in Skelton v Collins.

20

Again the High Court declined to follow the majority reasoning in a then recent House of

Lords decision.

21

Instead, it applied an earlier House of Lords decision

22 concerning the assessment of compensation for the estate of an injured person who had later died. Justice

Kitto stated: 23

The Court is not, in a strict sense, bound by such decisions, but it has always recognised and must necessarily recognise their peculiarly high persuasive value.

Moreover the reasoning of any judgment delivered in their Lordship’s House, whether

19

Frankland v R [1987] AC 576, 594.

20

(1966) 115 CLR 94.

21 H West and Son Ltd v Shephard [1964] AC 326.

22

Benham v Gambling [1941] AC 157.

23

(1966) 115 CLR 94, 104.

7 dissenting or concurring, commands and must always command our most respectful attention.

It was also decided that, where there is a clear conflict between a decision of the House of

Lords and the High Court upon a matter of legal principle, other Australian courts ought to follow the High Court.

24 Justice Windeyer suggested that the High Court should be cautious in its treatment of authorities of the House of Lords which made ‘reference only to English decisions . . . and seemingly to meet only economic and social conditions prevailing in

England’.

25

Following this decision, it was noted in Australia that ‘[a] new relationship of equality and mutual respect has emerged to replace the “colonial” attitude, clearly evident on both sides not so very long ago’.

26

Nevertheless, where there were no conflicting Privy Council or High

Court decisions, decisions of the House of Lords continued to be treated as ‘binding’ by some

Australian courts until as recently as the 1980s.

27

24

ibid 138–9 (Owen J (Windeyer J (at 133) and Taylor J (at 122) expressly concurred with these views)).

25 ibid 135.

26

E St John, ‘Lords Break from Precedent: An Australian View’ (1967) 16 ICLQ 808, 816.

27

See eg Kelly v Sweeney [1975] 2 NSWLR 720, 725 (Hutley JA); 738 (Mahoney JA). Cf

Samuels JA; Brisbane v Cross [1978] VR 49; Bagshaw v Taylor (1978) 18 SASR 564, 578

(Bray CJ); R v Darrington and McGauley [1980] VR 353; Life Savers (Australia) Ltd v

Frigmobile Pty Ltd [1983] 1 NSWLR 431, 433–4 (Hutley JA, with whom Glass JA agreed at

438); Horne v Chester and Fein Property Developments [1987] VR 913. Cf X v Amalgamated

Television Services (No 2) (1987) 9 NSWLR 575, 584 (Kirby P).

8

Confirmation by the Privy Council

As an indication of the growing pragmatism affecting the relationship of courts in England and Australia, the Privy Council acknowledged in Australian Consolidated Press Ltd v

Uren , 28 the entitlement of the High Court to adhere to its own earlier decisions where they conflicted with an earlier House of Lords precedent.

29

The case concerned the question of when exemplary damages should be awarded in a successful action for defamation. Lord

Morris of Borth-y-gest, in delivering the advice of the Privy Council, stated in plain terms that

‘[t]heir Lordships are not prepared to say that the High Court were wrong in being unconvinced that a changed approach in Australia was desirable’.

30 These words ‘sounded the death knell of mandatory uniformity of the common law’.

31

Persuasiveness of the reasoning

Appeals to the Privy Council from Australian courts were finally abolished in 1986.

32 The leading case on the status of English decisions in Australian courts following the removal of

28 [1969] 1 AC 590. Later confirmed in Geelong Harbour Trust Commissioners v Gibbs

Bright & Co (1974) 129 CLR 576.

29

Rookes v Barnard [1964] AC 1129.

30

[1969] 1 AC 590, 644.

31

WS Clarke, ‘The Privy Council, Politics and Precedent in the Asia Pacific Region’ (1990)

39 ICLQ 741, 743.

32

Appeals to the Privy Council were abolished in stages: first in federal matters (Privy

Council (Limitation of Appeals) Act 1968 (Cth)), secondly, appeals from the High Court

9 the Privy Council from the Australian judicial hierarchy is Cook v Cook .

33 The High Court, while acknowledging that Australian courts would ‘continue to obtain assistance and guidance from the learning and reasoning of United Kingdom courts’, stated: 34

Subject, perhaps, to the special position of decisions of the House of Lords given in the period in which appeals lay from this country to the Privy Council, the precedents of other legal systems are not binding and are useful only to the degree of the persuasiveness of their reasoning.

An emerging Australian common law

The statements made in the High Court in Parker v The Queen and Skelton v Collins , and the abolition of appeals to the Privy Council, contributed significantly to the recognition in

Australia of the existence of a distinctive ‘Australian’ common law.

35

Since these decisions,

(Privy Council (Appeals from the High Court) Act 1975 (Cth)), and finally, appeals from

State Supreme Courts (Australia Act 1986 (Cth) and (UK)). In Viro v R (1978) 141 CLR 88 the High Court held that it was no longer bound to follow decisions of the Privy Council, with minor possible exceptions.

33

(1986) 162 CLR 376.

34

ibid 390.

35

See eg J Toohey, ‘Towards an Australian Common Law’ (1990) 6 Aus Bar Rev 185;

Mason (n 8); A Mason, ‘The Common Law in Final Courts of Appeal Outside Britain’ (2004)

78 ALJ 183; L Zines, ‘The Common Law in Australia: Its Nature and Constitutional

Significance’ (2004) 32 Federal L Rev 337; J Chen, ‘Use of Comparative Law by Australian

Courts’ in AE-S Tay and C Leung (eds),

Australian Law and Legal Thinking in the 1990s. A

10 the High Court has deviated from the line taken by the House of Lords on a growing number issues, for example in relation to damages for gratuitous services,

36

the availability of exemplary damages,

37

immunity for barristers’ negligence,

38

the law of resulting trusts,

39 apprehended bias,

40

nervous shock,

41

the liability of local authorities,

42

and many other topics. collection of 32 Australian reports to the XIVth International Congress of Comparative Law presented in Athens on 31 July–6 August 1994 (Sydney: Faculty of Law, University of

Sydney, 1994) 64–5.

36

Hunt v Severs [1994] 2 AC 350. Cf Kars v Kars (1996) 187 CLR 354.

37

Rookes v Barnard [1964] AC 1129; Broome v Cassell & Co Ltd [1972] AC 1027. Cf Uren v John Fairfax & Sons Pty Ltd

(1966) 117 CLR 118. Gummow J notes that ‘in England, there are indications that the law may be turning, with the time being ripe for a reconsideration of

Rookes

’ (Gummow (n 7) 52). See

Kuddus v Chief Constable of Leicestershire Constabulary

[2002] 2 AC 122.

38

Arthur JS Hall v Simons [2002] 1 AC 615. Cf

D’Orta-Elenaike v Victoria Legal Aid

(2005)

223 CLR 1.

39

Tinsley v Milligan [1994] 1 AC 340. Cf Nelson v Nelson (1995) 184 CLR 538.

40

Dimes v Proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal (1852) 3 HLC 759, 10 ER 301; R v Bow

Street Magistrates, ex p Pinochet Ugarte (No 2) [2000] 1 AC 119. Cf Ebner v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy (2000) 205 CLR 337.

41

Alcock v Chief Constable of South Yorkshire Police [1992] 1 AC 310; White v Chief

Constable of South Yorkshire Police [1999] 2 AC 455.

Cf Annetts v Australian Stations Pty

Ltd (2002) 211 CLR 317; Gifford Strary Patrick Stevedoring Pty Ltd (2003) 214 CLR 269.

See W v Essex County Council [2001] 2 AC 592, where Lord Slynn considered that parents suffering from shock on learning of the sexual abuse of their children four weeks after the events might still come within a flexible concept of the immediate aftermath.

11

Consideration of House of Lords decisions in recent years

Today, at least in the High Court of Australia, it is never assumed that the judges will defer to

House of Lords authority. Nevertheless, as Chief Justice Gleeson recently observed, ‘[t]he influence of English decisions, although no longer formal, remains strong’.

43 Just as in recent times the House of Lords has increased its use of authority from Commonwealth courts, the antipodean courts have repaid the compliment. There has actually been an increase in the citation of House of Lords decisions by the High Court in recent years.

44

The High Court sometimes applies House of Lords decisions where the House of Lords has considered a particular issue first, such as the cases concerning rape in marriage 45 and the statutory

42

Anns v Merton LBC [1978] AC 728. Cf Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman (1985) 157

CLR 424; Jaensch v Coffey (1984) 155 CLR 549. In Murphy v Brentwood DC [1991] 1 AC

398 however, the House of Lords overruled Anns and followed the High Court decision in

Sutherland .

43

AM Gleeson, ‘The Influence of the Privy Council on Australia’ (2007) 29 Aus Bar Rev

123, 133.

44 See eg Burge v Swarbrick (2007) 232 CLR 336, in which case the High Court applied

George Hensher Ltd v Restawile Upholstery (Lancs) Ltd [1976] AC 64; A v State of New

South Wales (2007) 230 CLR 500, in which case the High Court followed Glinski v McIver

[1962] AC 726; Palmer Bruyn & Parker Pty Ltd v Parsons (2001) 208 CLR 388, in which case the High Court approved Smith New Court Securities Ltd v Scrimgeour Vickers (Asset

Management) Ltd [1997] AC 254; Spies v R (2000) 201 CLR 603, in which case the High

Court approved R v Scott [1975] AC 819.

45

R v R [1992] 1 AC 612; R v L (1993) 174 CLR 379. See Gummow (n 7) 54.

12 abrogation of legal professional privilege.

46 Justice William Gummow has reckoned that the extent of the interchange in decision-making by the High Court and House of Lords is possibly greater than before,

47

although this interchange ‘does not necessarily yield to concurrence of outcome’.

48

The link is now one of rational persuasion in a context of substantially shared basic legal doctrine. It is no longer a relationship of obedience or subservience.

Australian influence on the House of Lords

It has been suggested that the decisions in Parker v The Queen and Skelton v Collins contributed to the House of Lords decision in 1966 49 to abolish the rule that their own prior decisions on points of law were absolutely binding so that their effect could only be altered by

Parliament.

50

An experienced Australian advocate proposed that part of the reason for that change was ‘undoubtedly the attempt to preserve the Australian link in particular and the

46

R (Morgan Grenfell & Co Ltd) v Special Comr of Income Tax [2002] 2 WLR 1299; Daniels

Corp International Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2002) 213

CLR 543 at 582 [108], 593–4 [135]. The majority of the High Court limited the scope of the privilege in Grant v Downs (1976) 135 CLR 674. The House of Lords preferred the dissenting reasons of Barwick CJ in Waugh v British Railways Board [1980] AC 521. The High Court subsequently qualified Grant v Downs in Esso Australia Resources Ltd v Federal

Commissioner of Taxation (1999) 201 CLR 49.

47

Gummow (n 7) 54.

48 ibid.

49

Practice Statement (Judicial Precedent) [1966] 1 WLR 1234.

50

See St John (n 26) 810.

13 uniformity of the common law in general’ as the House of Lords would be able to ‘make due allowance for the opinions of other common law judges, in Australia and elsewhere’.

51

For most of the twentieth century, during the era of imperial authority, the House of Lords only very rarely drew upon decisions of Australian courts. In recent times, however, the

House of Lords has often referred to High Court decisions on a broad range of issues. For example, in the Deep Vein Thrombosis and Air Travel Group Litigation , Lord Scott of

Foscote said that the ‘most important DVT authority is the recent decision of the High Court of Australia in Povey v Qantas Airways Ltd

[2005] HCA 33’.

52

In Gilles v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions , a case concerning ostensible bias in a disability appeal tribunal, the

House of Lords accepted my own reasoning in Johnson v Johnson 53 regarding the meaning of the fiction by which such questions are judged—the reasonable and well-informed observer.

54

In R v Soneji (Kamlesh Kumar) , Lord Steyn commented that the joint reasons by the High

Court of Australia regarding the determination of the validity of an act done in breach of a statutory provision ‘contains an improved analytical framework for examining such questions.

In the evolution of this corner of the law in the common law world the decision in Project

Blue Sky

55 is most valuable’.

56

There are many other instances.

51

ibid 815.

52

[2006] 1 AC 495, 505. See now Povey v Qantas Airways Ltd (2005) 223 CLR 189.

53

(2000) 201 CLR 488.

54

[2006] 1 WLR 781, 784, 787, 793.

55 Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority (1998) 194 CLR 355, 390 [93]

(McHugh, Gummow, Kirby and Hayne JJ).

56

R v Soneji (Kamlesh Kumar) [2006] 1 AC 340, 353.

14

House of Lords’ influence on Australian law

It would exceed the ambit of this chapter to describe in detail the influence of House of Lords decisions on Australian law over the past two centuries. Virtually every area of the law has been affected by the reasoning in House of Lords cases. The fifth reported decision of the

High Court of Australia in 1904 was Chanter v Blackwood , 57 an electoral case that involved the application of the principle stated by the Lords in Julius v The Bishop of Oxford .

58

Using such cases in their reasoning became second nature to all Australian judges and lawyers. The

Appeal Cases and other reported series carried their Lordships’ decisions to the other side of the world. The Australian Law Journal , the national legal journal of record, noted the main decisions and changes in the course of authority.

59 Members of the House of Lords were typically the principal guests at the recurrent Australian legal conventions. Sometimes such visiting English judges planted ideas that were to have a large impact on judicial administration (permanent intermediate appellate courts are an instance).

60

57

(1904) 1 CLR 39, 52, 66.

58 (1880) 5 AC 214.

59

MD Kirby, ‘ Australian Law Journal at 80: Past, Present and Future’ (2007) 81 ALJ 529,

534.

60

R Evershed, ‘The History of the Court of Appeal’ (1950) 24 ALJ 346 stimulated the creation of the New South Wales Court of Appeal, later copied in most other courts. Apart from the decisions of the House of Lords, those of the English Court of Appeal were also normally followed in Australia in the absence of reliant High Court Authority: Public

Transport Commission v Murray-More (1974) 132 CLR 336.

15

Legal nationalism was a relatively quiescent force in the Australian judiciary and legal profession, even after the end of the Privy Council appeals which had reinforced the logic of using House of Lords authority. In part, this was the product of legal habits, legal education and professional conservatism. In part, it was the result of having the authorised English reports on the shelves of judges and advocates—a large investment reinforced by daily usage.

But mostly, it was a recognition of the practical utility and high intellectual distinction and persuasiveness of House of Lords reasoning. Every now and then, even today, judges in lower courts who have followed House of Lords authority unquestioningly, as if it were binding on them, need to be reminded of the new remit.

61

However, for the most part, the borrowing from House of Lords authority has been advantageous for Australian law. It rescued Australian judges and lawyers in a huge but sparsely populated country from narrow legal parochialism. From colonial times, it linked

Australian law to one of the great legal systems of the world in the heyday of its imperial and economic influence.

62

If in recent decades it was noticed that there was a need to consider the imports more closely for their suitability for a somewhat different society with different problems and values, this was merely another element in the evolution of the relationship of

Britain and Australia—from one of dutiful obligation to one of friendship, shared interests, and mutual regard.

61

See eg Channel Seven Adelaide Pty Ltd v Manock (2007) 82 ALJR 303, [138]–[141], a reference to the use of Kemsley v Foot [1952] AC 345. See also Koompahtoo Local

Aboriginal Land Council v Sanpine Pty Ltd (2007) 82 ALJR 345, [104].

62

FC Hutley, ‘The Legal Traditions of Australia as Contrasted with those of the United

States’ (1981) 55 ALJ 63, 69.

16

New Zealand

New Zealand courts were possibly even more obedient and unquestioning than Australian courts in their treatment of English precedent generally.

63

Prior to the establishment of a separate and permanent Court of Appeal in New Zealand, the primary policy concern of the

New Zealand courts appeared to be to avoid any departures from the common law in

England.

64

The New Zealand Court of Appeal was established in 1958. The influence of

English precedent was particularly powerful in its early years.

65

Given the size and composition of the population, the resources of the legal profession and the continuation of

Privy Council appeals, this was scarcely surprising.

Changing attitudes to English authority

The first murmurings of change in New Zealand occurred in Corbett v Social Security

Commission ,

66

when the New Zealand Court of Appeal followed a Privy Council decision

67

63

Decisions of co-ordinate courts in England were considered binding. See eg Barker v

Barker [1924] NZLR 1078 where the court rejected a line of earlier New Zealand cases in order to follow a decision of an English divisional court, Jackson v Jackson [1924] P 19, despite the fact that at least two of the New Zealand judges considered the English decision unsatisfactory.

64

BJ Cameron, ‘Legal Change Over Fifty Years’ (1987) 3 Canta L Rev 198, 209.

65 ibid 296.

66

[1962] NZLR 878.

67

Robinson v State of South Australia (No 2) [1931] AC 704.

17 which conflicted with a House of Lords decision.

68 Later, in Ross v McCarthy 69 the New

Zealand Court of Appeal expressly acknowledged that it was not bound to follow the House of Lords. The Court stated that decisions of the House of Lords were entitled ‘to be treated with the very greatest of respect and only departed from on rare occasions where for some good reason or another the law in New Zealand has developed on other lines’.

70

Nonetheless, in McCarthy , the Court applied the relevant House of Lords authority.

The real break came in Bognuda v Upton & Shearer Ltd .

71

The Court of Appeal was faced there with established House of Lords authority that was at variance with perceptions of the requirements of modern New Zealand law and society. In the result, the New Zealand Court of Appeal declined to follow the House of Lords decision in Dalton v Angus .

72 Justice North,

President, and Justice Woodhouse declared that, while House of Lords decisions were entitled to great respect, New Zealand courts were not bound by them as a matter of the law of precedent. The Court of Appeal clearly indicated a willingness to diverge from the House of

Lords line of thinking where it was considered inappropriate to New Zealand’s law and society. At the time, this decision was described as having ‘created a landmark in the development of New Zealand legal identity’.

73

68 Duncan v Cammell Laird and Co Ltd [1942] AC 624.

69

[1970] NZLR 449.

70

ibid 453–4 (North P, Turner J, and McCarthy J concurring).

71

[1972] NZLR 741; cf Ross v McCarthy [1970] NZLR 449.

72

[1991] 6 AC 740.

73 P Spiller, New Zealand Court of Appeal 1958–1996: A History (Wellington: Brookers Ltd,

2002) 391; J Smillie, ‘Formalism, Fairness and Efficiency: Civil Adjudication in New

Zealand’ [1996] NZ L Rev 254.

18

After the decision of Bognuda v Upton the Court of Appeal demonstrated a ‘much less inhibited approach to precedent and a greater readiness to use judicial reasoning to determine and develop the law’.

74

By 1982, it was observed that ‘[m]uch water has . . . passed under the bridge and it cannot now be said that this Court is bound by the House of Lords’.

75

Unremarkable as a matter of legal logic—given that the institutional link of New Zealand courts was only to the Privy Council and not to their Lordship’s House—the assertion of independence was still seen at the time as a striking and novel idea.

In 1996, the Privy Council recognised that the New Zealand Court of Appeal was entitled to depart consciously from English decisions on the basis that social conditions and the values of society in New Zealand were different from those of England.

76

The right to appeal to the

Queen in Council was only abolished in New Zealand in 2003 with the establishment of the

New Zealand Supreme Court as the nation’s final appellate body.

77

The move was controversial in some circles in New Zealand, usually on the expressed basis of the small size of the population. However, once again, the evolution of independent institutions was a natural development, at once inevitable and appropriate.

An emerging New Zealand common law

74

Cameron (n 64) 211.

75

North Island Wholesale Groceries Ltd v Hewin [1982] 2 NZLR 176, 195 (Somers J).

76 See Invercargill City Council v Hamlin [1996] 1 NZLR 513 (PC). See also Lange v

Atkinson [2001] 1 NZLR 257 (PC).

77

Supreme Court Act 2003 (NZ).

19

As in Australia, a separate New Zealand common law began to emerge in the 1980s. By 1987,

Sir Robin Cooke, then President of the New Zealand Court of Appeal and later himself a judicial member of the House of Lords, declared that ‘New Zealand Law . . . has now evolved into a truly distinctive body of principles and practices, reflecting a truly distinctive outlook’.

78

Thus, in Lange v Atkinson

79

the New Zealand Court of Appeal ‘found the constitutional air of New Zealand too pure to be contaminated by uncertain English common law restrictions on political expression imposed by defamation law’.

80

The New Zealand

Court of Appeal also deviated from the approach of the House of Lords in respect of recovery of economic loss,

81

intoxication as a defence to a criminal charge,

82

and recognition of invasion of privacy within tort law.

83

The House of Lords now considers decisions of New

Zealand courts 84 as indeed the reasoning of other foreign courts when, as often happens, they touch upon common problems. The links of language and basic legal doctrine are a great

78

Sir R Cooke, ‘The New Zealand National Legal Identity’ (1987) 3 Canta L Rev 171, 182.

79

[2000] 3 NZLR 385. See more recently A-G v Ngati Apa [2003] 3 NZLR 643 (CA) and

Hosking v Runting [2005] 1 NZLR 1.

80

A Lester, ‘The Magnetism of the Human Rights Act 1998’ (2002) 33 Victoria University of

Wellington L Rev 477, 477.

81 Invercargill CC v Hamlin [1996] 1 NZLR 513. Upheld by the Privy Council in Invercargill

City Council v Hamlin [1996] 1 NZLR 513.

82

R v Kamipeli [1975] 2 NZLR 610.

83

See Hosking v Runting [2005] 1 NZLR 1.

84

See eg R (on the application of Hurst) v Comr of Police of the Metropolis [2007] 2 WLR

726; JD v East Berkshire Community Health NHS Trust [2005] 2 AC 373; R v Smith [2001] 1

AC 146; Three Rivers District Council v Governor and Company of The Bank of England

[2000] 2 WLR 1220; Spring v Guardian Assurance plc [1995] 2 AC 296.

20 legacy of our history. The trans-national conversation between courts of high authority on issues of mutual interest is likely to expand still further with the creation of the Supreme

Court of the United Kingdom.

Reasons for divergence and the future influence of the House of Lords

The reasons why divergences in legal principle occur from time to time vary. Divergences in the common law are often attributed to the differences in social conditions in various jurisdictions. However, as Justice Gummow suggests:

85 a greater part will be played by the strength of the submissions by the respective counsel, the degree of judicial research in judgment writing, and, in the end, by differing views of strong-minded and experienced judges upon issues of fundamental principle.

The growing influence of European law on the content of the law of the United Kingdom may limit the use of some English cases as precedents for the development of legal principles in

Australia and New Zealand, at least in particular areas of the law. The fact that Australia does not have a constitutionally entrenched or statute-based national Bill of Rights is also significant.

86

Furthermore, the influence of House of Lords decisions is also limited by encroachments into traditional areas of the common law by statute law. Nonetheless, the basic

85

Gummow (n 7) 54. See also Mason (n 35) 190.

86 See J Spigelman, ‘Rule of Law—Human Rights Protection’ (1999) Aus Bar Rev 29; Mason

(n 35) 191. In recent years, however, statutory protection of basic rights has been introduced in the State of Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory.

21 similarities of much legal doctrine remain. Habit, utility, a common language, and the traditionally practical way of looking at legal problems ensure that a sharing of learning and experience is bound to continue in the foreseeable future—probably more in Australia and

New Zealand, in the long run, than in other Commonwealth countries outside the antipodes.

Just the same, Australian and New Zealand courts now consult jurisprudence from many other jurisdictions, including civil law jurisdictions.

87 Almost certainly, this will also become a feature of the new Supreme Court of the United Kingdom as it is cut loose from its imperial past and traditional associations, stirring to mark out for itself a new and distinctive role in the world community of final, national courts.

Conclusion

For a substantial part of the 20th century, the House of Lords of the United Kingdom, in its judicial role, exerted an immense influence on the courts of Australia and New Zealand. Only now, in the past decade or so, has the obedient, dependent attitude of courts in the former antipodean colonies begun to fade.

88 Australian and New Zealand courts are greatly indebted to the House of Lords for decisions on legal principle across the entire landscape of the common law. We continue to benefit from such decisions and now, the highest court in the

United Kingdom is sometimes also assisted by decisions of Australian and New Zealand courts.

87

See Gleeson (n 43) 133.

88 MD Kirby, ‘Reforming Thoughts from Across the Tasman’ in G Palmer (ed), Reflections on the New Zealand Law Commission: Papers from the Twentieth Anniversary Seminar

(Wellington: LexisNexis, 2007) 14.

22

It is inevitable that the automatic application of the reasoning of the final court of the United

Kingdom will decline, proportionately, in its influence on the elaboration of judicial opinions of the courts in Australia and New Zealand. Professional habits will change. New source materials will proliferate. Distinct linkages reflecting geography, the indigenous peoples, commerce, culture, and utility will be built. International law will grow in importance. Fresh contacts will be made, especially with other common law jurisdictions that represent the world wide progeny of the courts that began by clustering around Westminster Hall.

Courts elsewhere now proclaim their own independence and integrity. Yet it is the greatest tribute that can be paid to the courts of England, including the House of Lords, that a strong element of imitation survives. The content of the law will change. But the integrity of courts, the judicial methodology and the basic doctrines of the legal order constitute some of the most precious exports of the United Kingdom to the whole world. And the House of Lords has played a central role in this process during a time of imperial transition.