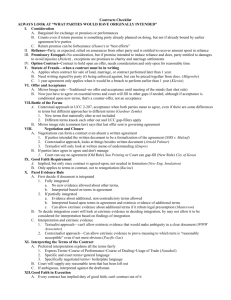

Contracts – Gordley – 2002 Fall – outline 3

advertisement